Following the inauguration of Donald Trump, the new US administration initiated a detailed analysis of US trading relations with the rest of the world. Its aim is to identify supposedly increasing “unfair trade practices” by other nations that threaten “well-paid American jobs.” The heated political debate over fair trade focuses on the US’ most important regional trading partners – Mexico and Canada – but large trade balance deficits with major partner countries like China and Germany have also come under fire. In the case of China, the US administration sees subsidies and discrimination against US companies as an unfair trade policy. In the case of Germany, it criticises domestic consumers’ weak appetite for US products. The administration has presented three protectionist trade policy measures as possible strategies for correcting what it perceives to be unfair trade, and for establishing a “level playing field.”

Many others have discussed recent US trade policy gyrations (e.g. Nordhaus 2017a, 2017b). There has even been a whole eBook on policy in the ‘Age of Trump’ (Bown 2017) which is partly dedicated to Trumpian trade policy. Our analysis contributes to this research by quantifying the potential outcomes of further US policies for the US and other countries at the sectoral level (Felbermayr 2017).

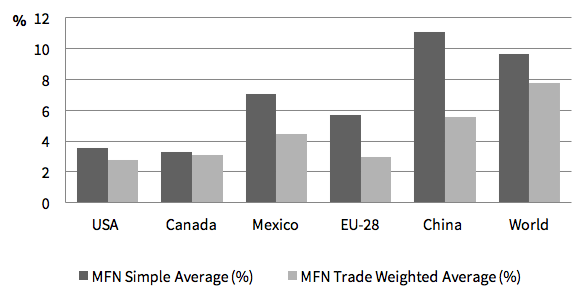

We start by noting that the US actually levies relatively low tariffs compared to its trading partners (Figure 1).1

Figure 1 Average most-favoured nation tariff by country, 2015 (percent)

Source: World Integrated Trade Solutions

In parallel to this liberal tariff policy, the US has been running a high trade deficit for many years, especially in goods trade.

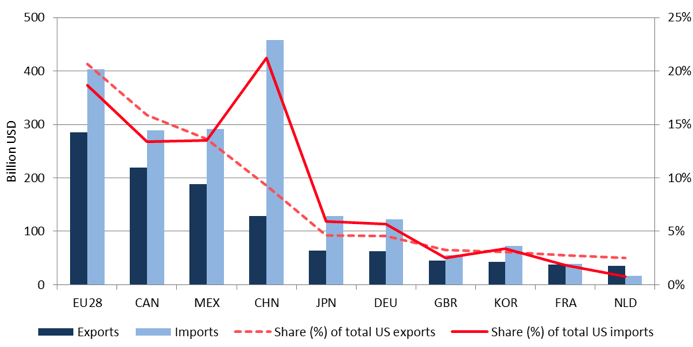

Substantial US trade deficits can be observed with eight of the ten top US trading partners (Figure 2). Considering these two phenomena – low tariffs and high trade deficits – it initially seems understandable that US political stakeholders regard the present trade structure as unfair. Moreover, US jobs are particularly concentrated in industries that suffer from the country’s open stance (Autor 2017). These interest groups unsurprisingly see the isolation of the US market as an effective cure.

Figure 2 US trade balance with its top 10 trading partners, 2015

Source: Baci World Trade Database

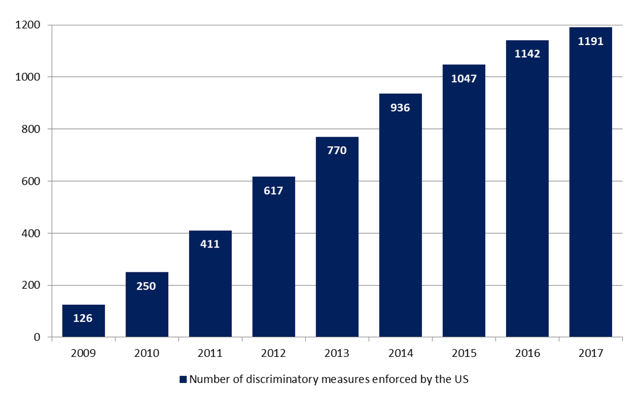

However, this assessment neglects non-tariff impediments that restrict trade flows. Figure 3 hints at substantial evidence of an increasing protectionist attitude from the US in the recent past. According to the recent data from the Global Trade Alert (GTA), the US is the most protectionist country within the group of G20 nations, as it implements by far the highest number of non-tariff barriers (see also Evenett and Fritz 2017).

Figure 3 Number of US discriminatory measures since 2009

Source: Global Trade Alert database.

Recent empirical studies illustrate that in the case of advanced economies, not only an increase in tariffs but, especially, an increase in non-tariff barriers is decisive for welfare losses. Thus, the communicated possible protectionist measures of the US might lead to severe economic consequences (Aichele et al. 2016).

The US has put the already very advanced negotiated trade agreements with both the EU and the trans-pacific countries on hold – TTIP and TPP will not be implemented for the time being. Official papers on the foreign trade strategy of the US president suggest renegotiating old agreements if goals such as the reduction of the trade deficit are not accomplished. The US has announced a renegotiation of the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA). In addition, the Korean agreement and the conditions for China’s WTO membership are candidates for US protectionism.

In light of these US trade policy developments, our study considers three possible protectionist trade policies whose implementation has been discussed by the Trump administration.

Our scenarios

1. Withdrawal from NAFTA

The first scenario considers the expected economic consequences of a reintroduction of US trade barriers with NAFTA countries. In doing so, possible tariff adjustments and non-tariff barriers between the NAFTA countries are taken into account. Blanchard (2017) offers a thorough explanation of the rationale behind the arising difficulties for the NAFTA agreement. We build on this analysis and quantify the consequences of a potential dissolution of the NAFTA.

2. Protectionist US trade policy with respect to the rest of the world

In principle, it is possible for the US to introduce an even stronger protectionist trade policy by systematically raising tariffs and non-tariff measures on all traded goods. Accounting for such a restrictive trade policy, in a second scenario, US tariffs are assumed to increase by 20% against all WTO member countries; retaliation of US trading partners causes tariffs against the US to be increased by 20%; and the US raises its non-tariff barriers by 20%. Furthermore, WTO countries equivalently introduce non-tariff barriers as retaliation measures against the US.

3. Introduction of a border tax adjustment

In 2016, US representatives Paul Ryan and Kevin Brady introduced a new tax reform. They proposed to decrease the federal tax on corporate profits from today’s 35% to 20%, to enable investments to become completely deductible, and to make international revenues subject to a so-called border tax adjustment. More concretely, exports are deducted from tax, while imports are added. Consequently, the system would tax consumption more heavily rather than production, and is thus equivalent to the European system of value added taxes. It thereby offsets the disadvantage of the (non-deductible) equity with the deductible foreign capital. This setup builds on Bown et al. (2017), which explains the concept of the border tax adjustment thoroughly (see also Buiter 2017 for an excellent treatment).

Our results

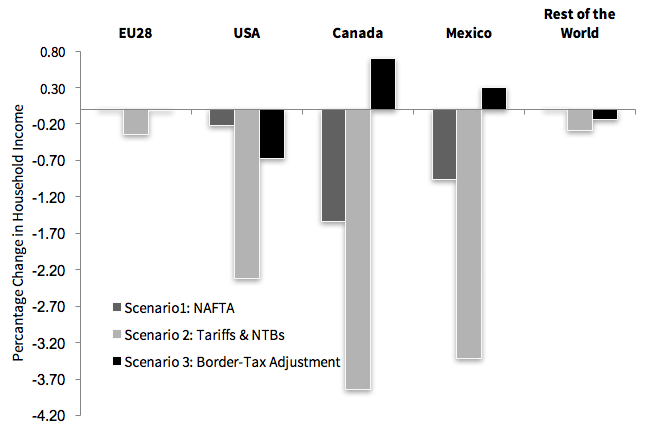

Figure 4 Percentage changes in household income following specific US trade policy

Source: Own calculations.

Our simulation for the three discussed US trade policies show very clear results:

US withdrawal from NAFTA

The revocation of the North American Free Trade Agreement would damage its member countries – the US, Canada, and Mexico – the most. Canada would be most affected as gross household income would decline by 1.54% over the long-run. Mexico and the US might lose 0.96% and 0.22% of gross household income, respectively. US exports of goods and services to Canada are predicted to contract by US$33 billion and to Mexico by $17 billion. Slightly increasing US export volumes to Europe and the rest of the world do not compensate for these losses. As a consequence of the protectionist US policies implemented, imports from Canada and Mexico would fall sharply. On aggregate, the import reductions from NAFTA countries would amount to $110 billion; trade diversion effects can only compensate to a small extent for this reduction. Additional imports worth $29 billion could be obtained from other countries, such as Germany. In nominal terms, imports from China, Japan, and Germany are expected to increase the most.

US protectionism against all WTO members with retaliation

Gross household income and real wages in WTO member countries would incur losses from increasing tariffs and non-tariff barriers. In particular, Mexico and Canada would experience disproportionate declines. Evidently, retaliative trade policy measures by WTO members against the US would not improve the situation in any country. In general, this can be attributed to the strong dependency of domestic economies on the US market. Nevertheless, individual countries would be able to reduce the potential loss through countervailing measures (e.g. a tariff increase), yet not one country could fully compensate the incurred contraction in gross household income and real wages. Vengeance should therefore not be the main response to threatened discriminatory US policies.

Border tax adjustment

The introduction of a border tax adjustment would cause US gross household income to contract by 0.67%. Other countries, such as Germany (-0.86%), the Netherlands (-0.74%) and South Korea (-0. 3%), would suffer even greater losses from a border tax than the US itself. On average, Europe would experience an increase in its gross household income of 0.04%. The aggregate effect of a US cash flow tax would cause a decline in total US exports and imports. In relative terms, US trade would decline homogeneously across all partner countries, while the relative magnitude of export contraction would be, on average, slightly higher than on the import side. At the sectoral level, an overall decline in exports and imports across nearly all sectors would be expected. The same picture can be found for other countries, albeit on a lower relative scale. Contrary to the communicated expectations of the US government, a border tax-based trade policy would only lead to decreasing global exports and imports.

The US protectionist trade policies discussed here generate benefits neither for the US itself nor for the rest of the world. The consequences of a withdrawal from NAFTA mainly affect its current members (Mexico, Canada, and the US); outside countries are hardly affected. The introduction of a border tax adjustment, however, touches all US partner countries to different extents. The impact of this on macroeconomic variables is still lower than in the case of US protectionist measures against WTO countries in combination with retaliative responses.

The fallacy of the protectionist promise

Our analysis clearly shows that the US administration’s promise to create more jobs and investment in the US through the presented trade policies is a fallacy. In all of the scenarios, the isolation of the US market would primarily have a negative impact on the US economy itself in the long term. It is also clear that a protectionist trade policy would most likely lead to a worldwide policy of retaliation against the US. In such a scenario, the threat of economic damage is again particularly pronounced for the US. These findings are similar to a recent study of Hufbauer and Jung (2017), who focus on the legal and economic aspects of Trump’s protectionism.

Clearly, there is need to support workers forced to reorient themselves as a result of intensified competition due to trade. However, these challenges should be addressed with policy instruments that do not distort trade, such as public support for training programmes (Qureshi 2017). At the same time, countries like China and Germany have to ask themselves whether their present trade surpluses are sustainable in the long term. In the case of Germany, this criticism should be put into context, because the surpluses are not induced by politics but can be explained, for example, by demographic ageing and the high saving rate that goes with it. The case of China is different. The relatively high level of isolation of the Chinese market and the simultaneous increase in overcapacity in individual industries, such as the steel sector, are leading to unfair trade with the US and are encouraging a rash political response in the US. Finally, it should also be pointed out that in the service industries – in which it still has a high competitive advantage – the US generally runs a trade surplus.

Concluding remarks

To sum up, our comprehensive analysis clearly discourages the US from pursuing the protectionist trade policy announced by its new administration for its own sake. Seeking new forms of cooperation with its main trading partners like China, Germany and the NAFTA partners would be a far more sensible strategy. First steps in this direction are to be found, for example, in the “Global Forum” for the global reduction of steel overcapacity and dumping. Such new coordination platforms are becoming increasingly necessary and help to identify new issues that can subsequently be tackled by existing international institutions like the WTO on a larger scale.

Finally, the US was the architect of the global, rules-based multilateral trading system. The country has consistently pushed ahead with the three pillars of the international economic system – the World Bank, the IMF, and the WTO. It is time for leading industrial countries to support the US in this endeavour in order to avoid a cutback in free trade. Here, beneficiaries of the US post-war policy – such as Germany, Europe and Japan – need to recognise that they bear a special responsibility and should step up to the challenge.

References

Aichele, R, G Felbermayr and . Heiland (2014), “Going Deep: The Trade and Welfare Effects of TTIP Revised”, ifo Working Paper No. 219.

Autor, D (2017), “What would the U.S. look like without the China shock?”, interview at IFS.

Blanchard, E (2017), “Renegotiating NAFTA: The role of global supply chains”, in C Bown (ed), Economics and Policy in the Age of Trump, CEPR Press.

Bown, C (2017), Economics and Policy in the Age of Trump, CEPR Press.

Buiter, W (2017), “Exchange rate implications of border tax adjustment”, VoxEU.org, 22 March.

Evenett, S and J Fritz (2017), Awe trumps rules: An update on this year’s G20 protectionism, CEPR Press.

Felbermayr, G, M Steininger and E Yalcin (2017), “Global Impact of a Protectionist U.S. Trade Policy”, ifo Forschungsberichte 89, ifo Institute.

Hufbauer, G and E Jung (2016), “Evaluating Trump’s trade policies”, VoxEU.org, 29 September.

Nordhaus, W (2017a), “The Trump doctrine on international trade: Part one”, VoxEU.org, 22 August

Nordhaus, W (2017b), “The Trump doctrine on international trade: Part two”, VoxEU.org, 23 August.

Qureshi, Z (2017), “The Not-So-Dire Future of Work”, Project Syndicate.

Endnotes

[1] In the study we present a more detailed picture of US tariffs against different trade partners, and on a disaggregated level.