The underrepresentation of some groups in academic economics has come to be seen as a problem. Indeed, one of the most august institutions in economics, the American Economic Association, has launched programmes and committees explicitly targeted at increasing the diversity of the profession. Most attention has focused on racial and gender diversity in economics (e.g. Bayer and Rouse 2016, Ndiaye and Ravn 2020, Hanspach et al. 2021), but there are other forms of diversity that are important in their own right. In a recent article (Angus et al. 2020), we discuss geographic diversity, by which we mean diversity in the locations where people, by choice or necessity, live and work.

Why should we care where economists, and in particular journal editors, live and work? We can think of two main reasons. First, it is possible that the environment in which one lives affects one’s thinking, so a lack of geographic diversity could lead to a suboptimal narrowing of perspectives. Second, it is possible that economists might exhibit bias in favour of those who inhabit the same ecosystem as themselves. If a key part of academic economics is driven by networks of friendship and reciprocity, and if geographic proximity helps to build these networks, then we might expect to see power within the profession concentrate in certain geographic areas to the exclusion of others. That is friendship networks and reciprocity could lead to a lack of fairness and objectivity in the assessment of academic contributions.

An important locus of power in economics presides at the editorial boards of academic journals. Academics need to publish in these journals to obtain tenure, promotions and pay increases. Consequently, the power of editors at these journals to decide whose papers are published and whose papers are rejected is both important and coveted (Heckman and Moktan 2018).

With this in mind, we have collected data on the institutional affiliations of people who serve in some editorial capacity at leading journals in the economics profession.1 Specifically, we considered the broad selection of 49 economics journals that were given the highest rating of A* on the Australian Business Deans 2019 journal quality list.2 Where present, affiliations listed on journal websites were used. Where journal websites did not list affiliations, this information was sourced from academic webpages. Location data were collected for institutional affiliations using Google Maps.

From our data, a series of striking facts emerged.

Editorial power is concentrated in the US

We mapped the geographic locations of editorial power within the economics profession by summing the number of editorial roles filled by academics at various locations (see Figure 1). It is immediately clear that a majority of power resides in the US. As the US is the centre of global academia, this in itself is unsurprising. However, the magnitude of US dominance is striking.

Figure 1 Geographic distribution of editorial power

In total, 63% of editorial power is in the US. That is, well over half of the editorial power at these 49 leading economics journals are located in a single country. North America as a whole accounts for 66% of power, Europe 27%, and the rest of the world 7%.

There are four major clusters of power in the US, centred on Northern California, Southern California, the central-northern part of the country and the north-east coast. Any one of the states of California, Massachusetts and Illinois has more power than the four continents of Asia, South America, Africa and Australasia combined.

The only other hub of comparable power to the four major US hubs is London. In fact, even relatively minor centres of power in the US, such as North Carolina or East Texas, would be powerful hubs in any other part of the world. For example, Duke University has more power (42 editorial affiliations) than Japan and China combined (38). The most powerful institution in the world outside of North America and Europe, Monash University (14), is only as powerful as the 32nd most powerful institution in North America, but it would rank 8th if it were in Europe. Table 1 summarises the rankings by academic institution.

Figure 2 Power in academia: US vs rest of the world

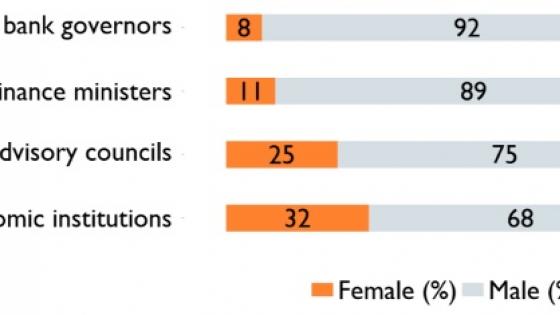

Figure 3 Economic institution power

Table 1 Country and university rankings by editorial power

Note: values in parentheses are the measures of editorial power.

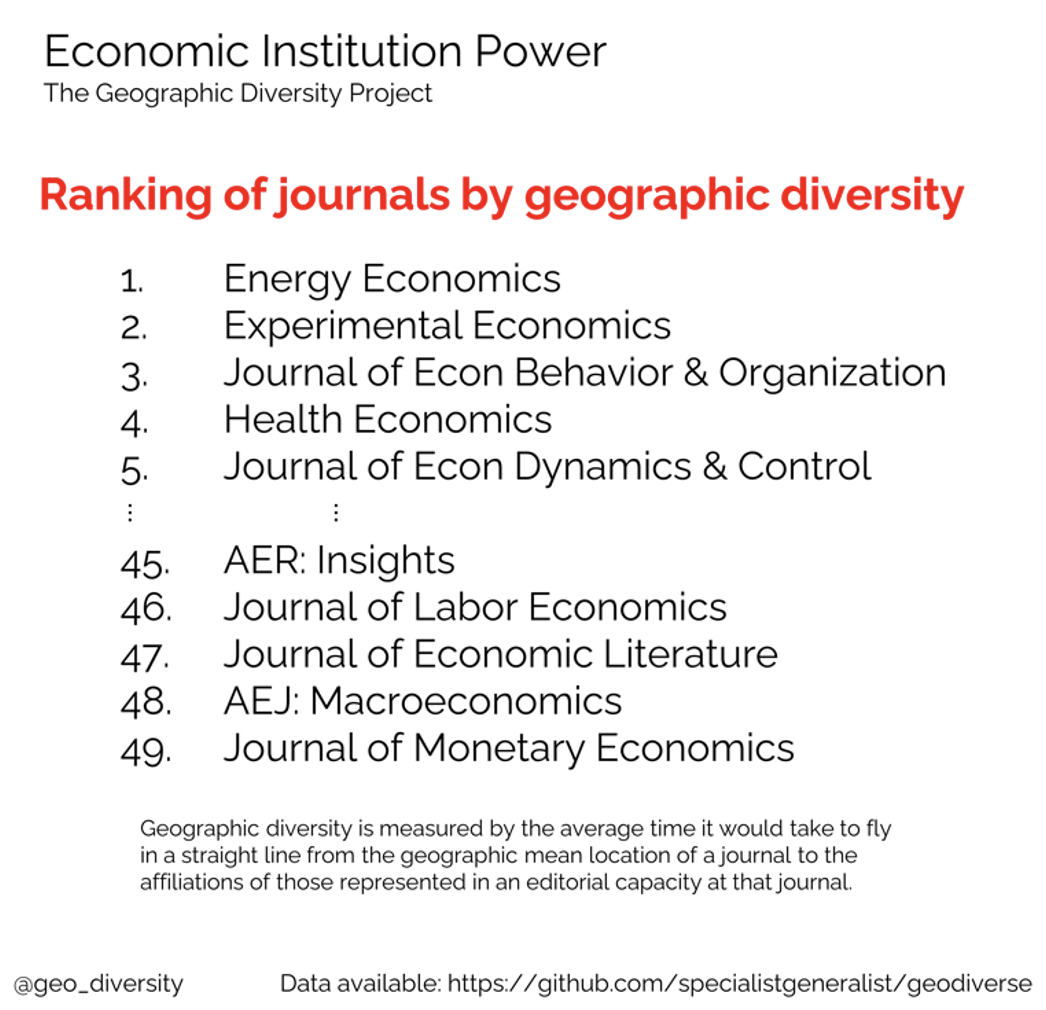

Figure 4 Rank of journals by geographic diversity

Geographic diversity varies across journals

We used our data to calculate a geographic centroid, a type of geographic average for the editorial power at each journal. The proximity of such centroids to the US gives an idea of how US-centric journals are relative to one another. For example, the centroids of many journals lie within North America, reflecting the overwhelming influence of US-based academics on their editorial boards. Centroids of journals with a higher share of European influence such as the Review of Economic Studies and the European Economic Review have their centroids in the middle of the Atlantic. Journals with European and Asian influence such as Energy Economics and the Journal of Economic Behavior and Organization have their centroids pulled up towards the Artic Circle.

The average great circle distance of the journal’s editorial affiliations from this geographic centroid can be considered a measure of the geographic diversity of the journal’s editorial team. This average distance is known as the standard distance (Bachi 1962) and is similar to standard deviation in that it is a measure of statistical dispersion. The higher the standard distance, the more geographically diverse the journal. This allows us to rank journals by geographic diversity.

Comparing standard distances, we find that, on average, newer journals tend to be more geographically diverse, except for several journals founded by the American Economic Association and Econometric Society between 2009 and 2019 that exhibit extremely low geographic diversity. These journals have little representation from outside the US. In fact, the American Economic Review: Insights has none. Within economics, the diversity of journals varies across fields. Economic theory and econometrics journals are, on average, more geographically diverse than applied journals. This reflects a greater European and Asian contribution to such journals. However, applied journals are the most heterogeneous in terms of diversity: some of the most and the least geographically diverse journals are applied journals.

Journals are more geographically diverse in the authorial dimension than the editorial dimension

To compare with our editorial findings, we collected data from Scopus and Google Maps on the geographic location of authors publishing in our journals in 2019 and 2020. The resulting data were used to map authorial power at gridded locations across the globe and to calculate the geographic centroid of the authorship of each journal.

We find a positive correlation between the geographic diversity of a journal’s editors and the geographic diversity of its authors. That is, journals with a more diverse editorship are likely to have a more diverse authorship. There are many reasons that this could be so. In particular, it is worth noting that causality could go in both directions. For example, although editors may be more likely to accept work by those closer to them in the social network and thus geographically closer to them, it may also be the case that publishing frequently in a journal increases the chance of being asked to participate in the editing of that journal.

Importantly, for a large majority of journals, the authorship is more geographically diverse than the editorship (see Figure 5). This is driven primarily by the fact that a greater share of editors than of authors is based in the US. As a consequence, even journals with a diverse set of editors relative to other journals may have a non-diverse set of editors relative to their authorship.

Figure 5 Editorial and authorial geographic diversity

The Far East is hugely underrepresented in terms of editorial power

In general, authorship in prestigious journals and editorial power at such journals tend to go hand in hand. However, relative to editorial power, authorship is shifted to the East. Specifically, the share of authors from outside of the US is typically higher than the share of editors from outside of the US. It is particularly noteworthy that academics based in East Asia contribute significantly to authorship in prestigious journals but hold a tiny share of editorial positions (see Figure 6). If there is any aspect of our data that one might expect to change in the long term, it is this. As the rise of China and the surrounding region continues, it seems unlikely that such a salient power differential will be allowed to persist.

Figure 6 Geographic density of editors and authors

Paths forward

Our work on this topic has led to stimulating discussion on Twitter and other social media. Views range considerably. At one end of the spectrum, a fraction of commentators thinks that the dominance of the US in editorial positions is simply a reflection of the overwhelming superiority of US academia. Such people tend to believe the current system to be both fair and efficient. At the other end of the spectrum are those who think the process of recruiting for editorial boards to almost entirely reflect networks of patronage in which powerful people look after their friends and students. Such people tend to believe the current system to be unfair and inefficient. Most people believe the true process to be a mix of the above.

Our recent work (Angus et al. 2020) contributes by giving an accurate snapshot of how power is distributed in the profession. The debate over how the allocation of power should and will continue to evolve is ongoing. We note that institutional concentration and a lack of geographic diversity is not unique to economics (e.g. Espin et al. 2017, Goyanes and Demeter 2020, Lohaus and Wemheuer-Vogelaar 2020). However, given the current focus on diversity in the economics profession, now may turn out to be an ideal time for progress to be made in addressing the issue.

References

Angus, S D, K Atalay, J Newton and D Ubilava (2020), “Geographic Diversity in Economic Publishing”.

Bachi, R (1962), “Standard distance measures and related methods for spatial analysis”, Papers of the Regional Science Association 10(1): 83–132.

Bayer, A and C E Rouse (2016), “Diversity in the economics profession: A new attack on an old problem”, Journal of Economic Perspectives 30(4): 221–242.

Espin, J, S Palmas, F Carrasco-Rueda et al. (2017), “A persistent lack of international representation on editorial boards in environmental biology”, PLoS Biology 15(12): e2002760.

Goyanes, M and M Demeter (2020), “How the geographic diversity of editorial boards affects what is published in JCR-ranked communication journals”, Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly 97(4): 1123–1148.

Hanspach, P, V Sondergeld and J Palka (2021), “Few top positions in economics are held by women”, VoxEU.org, 15 February.

Heckman, J and S Moktan (2018), “Publishing and promotion in economics: The tyranny of the Top Five”, VoxEU.org, 01 November.

Lohaus, M and W Wemheuer-Vogelaar (2020), “Who publishes where? exploring the geographic diversity of global IR journals”, International Studies Review, in press.

Ndiaye, A and M Ravn (2020), “Organising a high-quality conference with equal access: Lessons learned from VMACS Junior Conference”, VoxEU.org, 21 September.

Endnotes

1 Data were collected between 28 July 2020 and 3 August 2020.

2 https://abdc.edu.au/research/ abdc-journal-list/