Suffrage institutions historically excluded large parts of society from political influence and arguably affected long-run development through biased tax systems and public goods provision (Engerman and Sokoloff 2005). Even today, it is well documented that political representation is highly skewed towards the wealthy (Bartels 2016, Gilens 2012). Unequal voting rights are thus of both historical and contemporary relevance. Concentration of political power in the hands of a small economic elite alongside a vast majority of the population without effective rights has been associated with the adoption of policies that mainly benefit the elite (Acemoglu et al. 2001, 2002).

While unequal voting rights were common throughout history (for example, votes depended on land ownership or tax contributions), on the eve of WWI Prussia was the last major country in the industrialised world to maintain a franchise that was unequal, non-secret, and indirect, all at the same time. Since 1850, members of the Prussian Parliament were elected under the so-called three-class franchise system, which translated tax payments into voting weights. Voters were grouped into three classes (Abteilungen) by total direct taxes paid. Each of the three classes represented one third of the total direct tax revenue and received the same number of votes. Classes were filled with voters ranked according to their tax payments, starting from the highest, adding taxpayers until one third of the total tax base was reached, thereby allocating less than 5% of voters into the first class, on average.

Gerschenkron (1966: 25) argued that, due to this unequal and indirect Prussian franchise, the land-owning elite (the Junkers) dominated both chambers of the Prussian Parliament and could thus veto any legislation in the Federal Council of the German Empire. Indeed, the political orientation of the Prussian Parliament overall was rather conservative, as exemplified by the fact that Social Democrats were not able win any mandates until 1908 and suffrage reforms were repeatedly rejected until 1918 (Ziblatt 2008). Nevertheless, the three-class franchise also gives the unique opportunity to study the regional variation in vote inequality stemming from differences in the income distribution, to understand whether a higher concentration of votes is associated with a higher preference for conservative policies.

On average, first-class voters had about 17.5 times the number of votes of third-class voters, obscuring much stronger inequality at the local ward (Urwahlbezirk) level. In the extreme, a single taxpayer who paid a third or more of direct taxes in a ward would have as many votes as all of the taxpayers in the lower tercile combined. The most prominent example was the industrialist Alfred Krupp who was the only voter in the first class in his ward. At the other extreme, in the theoretical case of a uniform distribution of tax payments, all votes receive equal weights.

While the three-class franchise was designed when industrialisation was in its infancy, with rapid industrialisation, industrialists like Krupp became increasingly influential and income inequality rose (Kuznets 1955, Bartels 2019). It is thus far from clear that landownership inequality dominates vote inequality in influencing policies in the Prussian Parliament.

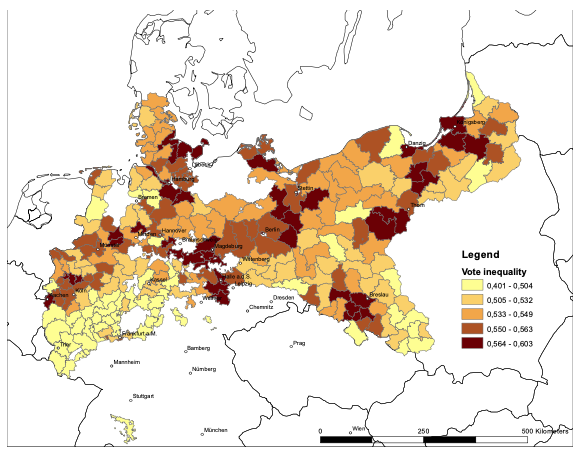

Figure 1a Vote inequality

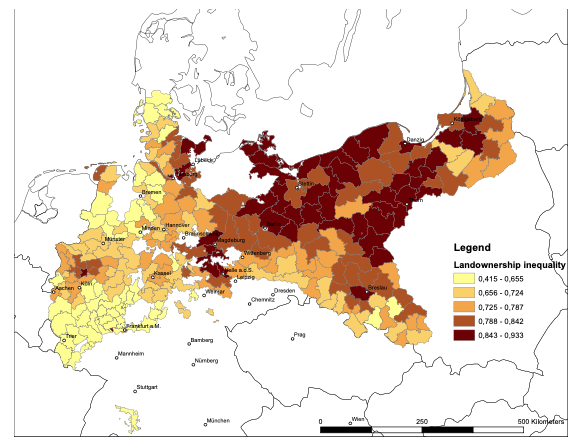

Figure 1b Landownership inequality

Note: The figure shows the spatial distribution of vote inequality and landownership inequality. Vote inequality is a Gini coefficient calculated using the county-level number of voters in each class in the three-class franchise system of 1893 assuming that the tax burden of each class amounts to exactly one third. Landownership inequality is a Gini coefficient calculated using the county-level number of farms with arable land by size-class (up to 1 hectare, 1 to 2 ha, 2 to 10 ha, 10 to 50 ha, 50 to 100 ha, and more than 100 ha) in 1882.

Source: Becker and Hornung (2020).

Figure 1 displays the spatial distribution of vote inequality (panel a) and landownership inequality (panel b) across Prussia. Regions with high levels of vote inequality, as measured by a Gini coefficient across franchise classes, can be found throughout Prussia, especially in more urban and industrial locations. The spatial distribution of landownership inequality, as measured by a Gini coefficient across farm size classes, shows that landownership inequality concentrates in the more rural eastern provinces. A comparison of the two maps visually confirms our above interpretation that the mechanics of the franchise system may have provided political rents to an industrial elite and were not exclusively captured by the agrarian elite.

In a recent paper (Becker and Hornung 2020), we exploit variation in vote inequality across Prussian constituencies to study how MPs voted in (all) 329 roll call votes (RCVs) in the Prussian Parliament in the period 1867-1903.

We follow the political science literature and analyse RCVs using the non-parametric optimal classification (OC) method introduced by Poole (2000). Similar to a principal component analysis, the OC method extracts one or more latent variables from the votes that are fed into the algorithm. In the Prussian case, the OC algorithm gives us two OC scores that we interpret to capture a liberal-conservative dimension and a secular-religious dimension of policy making.

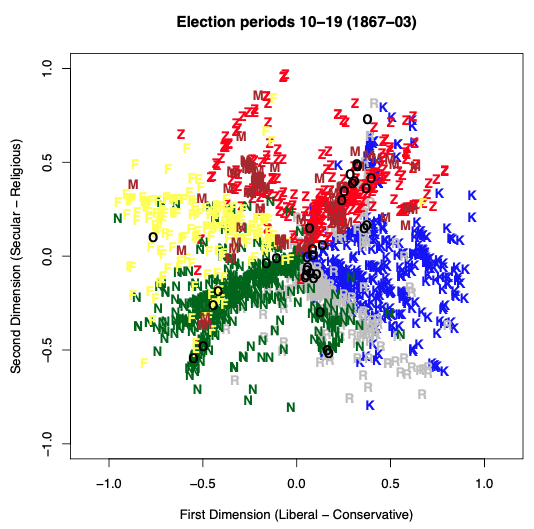

Figure 2 The Prussian policy space during election periods 10–19

Note: Positions of MPs in the Prussian House of Representatives. Each shape represents the political orientation of an MP based on his voting behaviour during all roll calls in the period 1867–1903. For interpretation of the colours and letters assigned to different parties, please see the main text.

The output of the OC algorithm – the two dimensions of an MP’s political orientation – are presented in Figure 2. The two coordinates that reveal the position of each MP within a unit circle, in other words, coordinates assume values between -1 and +1. Colours and letters indicate party membership: at the liberal end of the spectrum are Left Liberals (yellow F), followed by the National Liberals (green N), parties representing Minorities (brown M) such as Danes or Poles, the (mainly) Catholic Zentrum/Centre Party (red Z), the Free Conservatives (grey R) and at the most conservative end the Conservatives (blue K). This ordering reflects the fact that parties are groups of like-minded people, i.e. MPs belonging to the same party are more likely to vote in a similar way. At the same time, since party discipline in roll call votes is far from perfect, there is substantial variation in MP roll call voting within parties. On the secular-religious dimension, the Catholic Zentrumspartei is naturally at the more religious end of the spectrum.

Having described the policy space in the Prussian Parliament in the period 1867-1903, we ask whether indeed higher vote inequality translates into more conservative roll call voting behaviour of MPs, as one might expect if landed elites are the dominant force? Our key finding, based on a regression analysis, is that higher vote inequality at the constituency level is associated with more liberal roll-call voting by the elected MPs. This finding holds conditional on landownership inequality which, by itself, leads to more conservative voting. We can also control for characteristics of the local population (share of Protestants, urbanisation, industrial employment, etc.) and for MP characteristics. Our results also hold conditional on regional fixed effects and party indicators, even though of course these party dummies absorb a substantial part of the variation in MP orientation.

All along, we treat the secular-religious dimension as a placebo dimension as we do not expect a link between vote inequality and voting along this dimension, and this indeed the case.

Despite the extensive number of control variables, our estimates may be biased if unobserved variables correlate with both the distribution of voters across classes and the political orientation of the MP. We address this concern in an instrumental variable (IV) approach that exploits variation in the share of voters in the first class. We can do this because the local threshold that allocates voters to the three classes is somewhat arbitrary. Assignment to the first class is not within each individual taxpayer’s power but is largely determined by the share of tax payments coming from the individual with the highest income. The exact number of voters in the first class is therefore plausibly exogenous to systematic heterogeneity in local conditions. Our IV approach confirms the findings from the main regression analysis.

So, what might explain that higher vote inequality translates into more liberal voting, despite the alleged power of the Junkers? We argue that toward the end of the 19th century, vote inequality became increasingly concentrated in urban regions with large-scale industrialisation. Here, the highly concentrated economic elite managed to agree on their preferred MP, because small groups of homogeneous voters find it easier to coordinate on outcomes. While this may be similar in rural areas where the rural elite resided, coordination costs are lower in industrial urban areas because of higher population density, better transport infrastructure, and lower information costs. We therefore expect a stronger link between vote inequality and liberal voting in areas with industrial elites.

To test this hypothesis, we focus on the effect of vote inequality in regions with a high share of large firms. In these regions, the effect should be amplified if owners of large-scale industrial firms that arguably benefit from liberal policies climbed to the top of the income distribution during the industrial revolution. We indeed find that the effect increases in magnitude when focusing on these regions. This finding corroborates our interpretation that large-scale industrialists were able to take advantage of the franchise system and elected delegates who voted for liberal policies. We thereby lend support to the view that historically, economic elites were not a monolithic group, but that some may have favoured liberalisation and modernisation for self-serving reasons.

References

Acemoglu, D, S Johnson, and J Robinson (2001), “The Colonial Origins of Comparative Development: An Empirical Investigation”, American Economic Review 91(5): 1369–1401.

Acemoglu, D, S Johnson, and J Robinson (2002), “Reversal of Fortune: Geography and Institutions in the Making of the Modern World Income Distribution”, Quarterly Journal of Economics 117(4): 1231–1294.

Bartels, C (2019), “Top Incomes in Germany, 1871–2014”, Journal of Economic History 79(3): 669–707.

Bartels, L M (2016), Unequal Democracy: The Political Economy of the New Gilded Age, Princeton University Press.

Becker, S O and E Hornung, (2020), “The Political Economy of the Prussian Three-Class Franchise”, forthcoming at the Journal of Economic History (earlier version published as CEPR Discussion Paper 13930).

Engerman, S L and K L Sokoloff. (2005), “The Evolution of Suffrage Institutions in the New World”, Journal of Economic History 65(4): 891–921.

Gerschenkron, A (1966), Bread and Democracy in Germany. New York: Fertig, new ed.

Gilens, M (2012), Affluence and influence: Economic inequality and political power in America, Princeton University Press.

Kuznets, S (1955), “Economic Growth and Income Inequality”, American Economic Review 45(1): 1–28.

Poole, K T (2000), “Nonparametric Unfolding of Binary Choice Data”, Political Analysis 8(2): 211–237.

Ziblatt, D (2008), “Does Landholding Inequality Block Democratization?: A Test of the ‘Bread and Democracy’ Thesis and the Case of Prussia”, World Politics 60(4): 610–641.