Throughout their careers, workers experience times of prosperity and also go through economic hardship. Events such as promotions, new job offers, job loss, suffering an illness, and so on are all examples of positive and negative surprises that make labour income volatile. This volatility is often referred to as earnings risk. While individuals face earnings risk day after day, there are times when the macroeconomic conditions affect the chances of positive and negative surprises occurring. How exactly the probability of income losses (downside risk) and the probability of income gains (upside chance) vary systematically from expansions to recessions is still an open debate. Early studies that approached this question typically restricted their attention to the variance of income changes. A prominent example is a study of Storesletten et al. (2004), who implicitly imposed the assumption that downside risk and upside chances move in the same direction, and concluded that recessions are times when both the probability of income losses and income gains increase. Recently, studies such as Arellano et al. (2017) or Guvenen et al.(2014) have challenged this symmetric characterisation of income risk. Focusing on the business cycle, Guvenen et al. documented that, while it is true that downside risk increases in recessions, the chances of positive changes in income decrease. These two observations in conjunction are what we refer to as asymmetric business-cycle (earnings) risk.

While individual income fluctuations are important, various private and public insurance channels prevent these fluctuations from affecting an individual's consumption. Two prominent sources of such insurance are the family and the government. Within a family, spouses can in principle react to the negative surprises of their partner. For example, if one partner becomes unemployed, the other can try to enter the labour market. This kind of within-family insurance has been documented in, for example, Attanasio et al. (2005), or more recently in Blundell et al. (2016). Governments in developed economies operate rich tax and transfer systems, parts of which are specifically designed to insure individuals against income losses – most prominently unemployment insurance. But how well do these insurance channels function in recessions? Or, phrased differently, are they successful in smoothing cyclical fluctuations in individual income risk?

In a recent working paper, we provide a broad perspective on both individual income dynamics and insurance mechanisms over the business cycle and study panel data on individuals and households from three countries: the US, Germany, and Sweden (Busch et al. 2018). These countries differ in important aspects relevant for our analysis, such as household structures, the extent of their social safety nets, labour market institutions, and sectoral composition. The data sets we use are based on social security records (SIAB for Germany), tax register data (LINDA for Sweden), and household surveys (PSID for the US and SOEP for Germany), and cover more than three decades in each country.

We now move step-by-step from individual labour earnings before taxes and transfers to household income after taxes and transfers, and analyse the business cycle variation of downside risk and upside chances. By doing so, our analysis yields three sets of results.

- First, in all three countries, downside risk in before-tax-and-transfers individual income increases in recessions, while upside chances are lower.

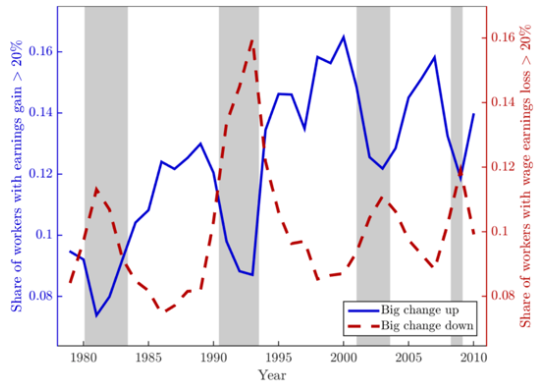

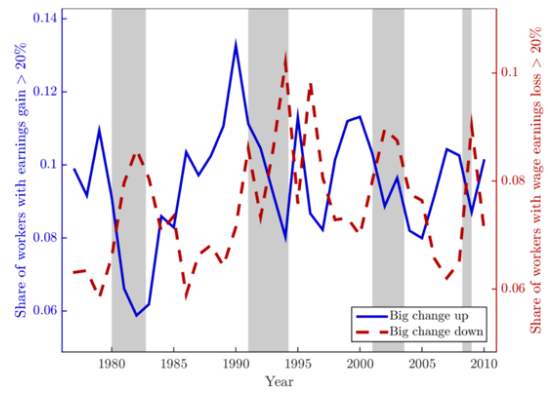

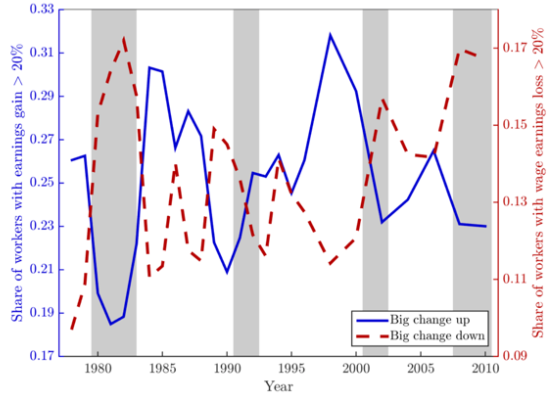

To illustrate this, Figure 1 shows that, in all three countries, the share of workers realising an earnings loss of more than 20% from one year to the other typically increases in recessions, and vice versa for income gains.1

Figure 1 Share of workers with earnings gain/loss > 20%

A) Sweden

B) Germany

C) US

Note: Shaded areas indicate recessionary periods.

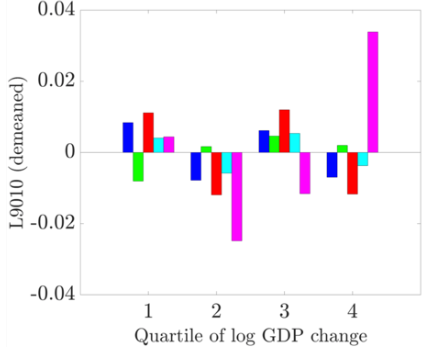

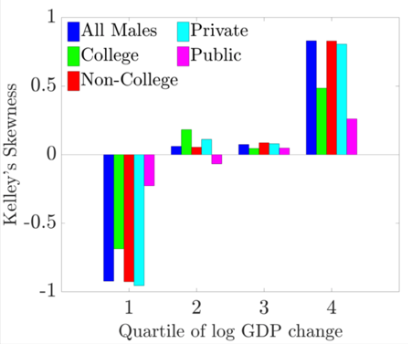

One statistic that summarises those asymmetric changes is called Kelley’s skewness – it gives a notion of the relative size of upside chances to downside risk. We show it in Figure 2, together with a measure of the overall dispersion of income changes. The figure shows that overall dispersion is acyclical (panel a) and skewness is procyclical (panel b). In other words, downside risk becomes more prevalent in recessions, while there is no systematic change in dispersion over the business cycle. This holds broadly for several sub groups defined by education, and by private and public employment. In our paper, we show that the results are also qualitatively similar for women. We further refine our empirical analysis of the cyclical patterns separately for each country, and show that the general pattern is very robust across countries and groups of the population – over the business cycle, downside risk and upside chance move in opposite directions.

Figure 2 GDP change

Panel A

Panel B

Note: For different samples, each bar shows the average moment across years and countries by quartiles of log GDP change. Both log GDP changes and moments are standardised by country.

- Second, moving to before-tax-and-transfers household income, we find evidence that households are not very effective at mitigating asymmetric business cycle fluctuations in individual-level incomes.

This does not contradict the existence of family insurance in general.

Instead, it points towards family insurance reaching its limits in particularly hard times, and is consistent with a lower ability of each spouse to respond to the other's income change in recessions. Also, to the extent that spouses work in, for example, the same regional labour market or industry, they can be expected to be exposed to the same regional economic conditions. When one partner loses the job due to a major employer of a region going bankrupt in the recession, the spouse will potentially not find employment easily. Given this lack of private insurance, the role for insurance provided through government policy is potentially large – but how successful are the existing tax and transfer schemes? This is the question we turn to next.

- Third, we move to after-tax-and-transfers household income – that is, income after all government tax and transfer programmes are accounted for – and find that government tax and transfer programmes blunt some of the largest declines in incomes in recessions.

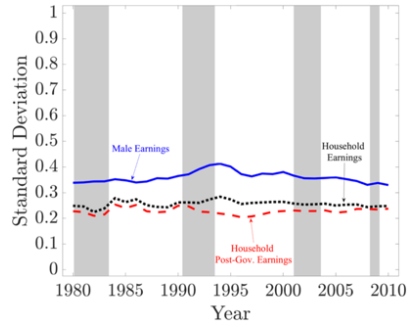

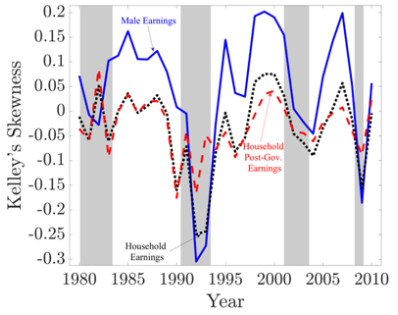

To further illustrate our results, Figure 3 shows the time-series of the standard deviation and skewness exemplarily for Sweden. Still, the remaining cyclicality of skewness is substantial – through the lens of a structural macroeconomic model that we estimate using our empirical results for Sweden, we find a large welfare gain from further reducing skewness fluctuations for households.2 This means that policies aiming to dampen downside risk potentially have a large impact on social welfare.

Figure 3

Panel A

Panel B

Note: Linear trend removed, centred at sample average. Shaded areas indicate recessionary periods.

We then explore if the reduction in cyclicality of skewness is driven by less downside risk in recessions or less upside chances in booms, and which elements of the tax and transfer system account for the overall success in reducing cyclicality. We find that in all three countries labour-market related transfers (primarily unemployment benefits) generate lower downside risk. On top of this, the tax system further reduces downside risk in the US and Germany, whereas in Sweden it mainly reduces the increase of upside chance in booms.

References

Attanasio, O, H Low, and V Sanchez-Marcos (2005), “Female labor supply as insurance against idiosyncratic risk”, Journal of the European Economic Association 3(1-2), 755-764.

Blundell, R, L Pistaferri, and I Saporta-Eksten (2016), “Consumption inequality and family labor supply”, American Economic Review 106(2), 387-435.

Busch, C, D Domeij, F Guvenen, and R Madera (2018), “Asymmetric Business-Cycle Risk and Social Insurance”, Barcelona GSE Working Paper Series, no. 1031.

Guvenen, F, S Ozkan, and J Song (2014), “The Nature of Countercyclical Income Risk”, Journal of Political Economy 122(3), 621-660.

Heathcote, J, K Storesletten, and G Violante (2014), “Consumption and Labor Supply with Partial Insurance: An Analytical Framework”, American Economic Review 104(7), 2075-2126.

Storesletten, K, C Telmer, and A Yaron (2004), “Cyclical Dynamics in Idiosyncratic Labor Market Risk”, Journal of Political Economy 112(3), 695-717.

Endnotes

[1] The results shown for Germany are based on the SIAB.

[2] In particular, we estimate a variant of the partial insurance model of Heathcote et al. (2014). For Sweden, we find that the degree of overall insurance provided by the existing tax and transfer system amounts to a welfare gain of 1.3% in consumption equivalent terms: that is, taxes and transfers provide the same gain as adding 1.3% to the consumption expenditures of households. However, the remaining risk (in post-government household-level income) is still substantial: households are willing to pay 4.6% of their consumption to completely eliminate procyclical fluctuations in skewness.