The European Commission communication for a reform of the EU economic governance framework aims to provide the basis for convergence across Member States on the way forward (European Commission 2022, Buti et al. 2022). It has drawn lots of attention. Most recognise that the Commission has put forward a far-reaching proposal aiming at finding a balance between different views in the complex debate on how the rules should be changed.

In particular, several elements have been considered as important improvements compared to the current rules, most notably (i) taking a medium-term perspective; (ii) increasing the differentiation across Member States based on their debt sustainability; (iii) streamlining the fiscal indicators by focusing on observable net expenditure ceilings; and (iv) integrating better the need for fiscal adjustment with that of supporting investment and reforms (Bordignon 2022, Blanchard et al. 2022).

Certain other features have been met with some criticism. In broad terms, the critical remarks pertain to the institutional aspects, the economic implications and the technical features of the Commission’s approach. Given the attention that stakeholders are paying to the Commission orientations, it appears important to address those misgivings along the three areas just sketched out.

Institutional criticisms

A major criticism that has been emerging concerns the role played by the Commission in the design and assessment of the national fiscal-structural plans (Blanchard et al. 2022, Lorenzoni et al. 2023, Wyplosz 2022), which is considered to lead to a bilateral approach that would undermine transparency and equal treatment. These authors suggest boosting the role of the independent national fiscal councils as a way to ensure national ownership.

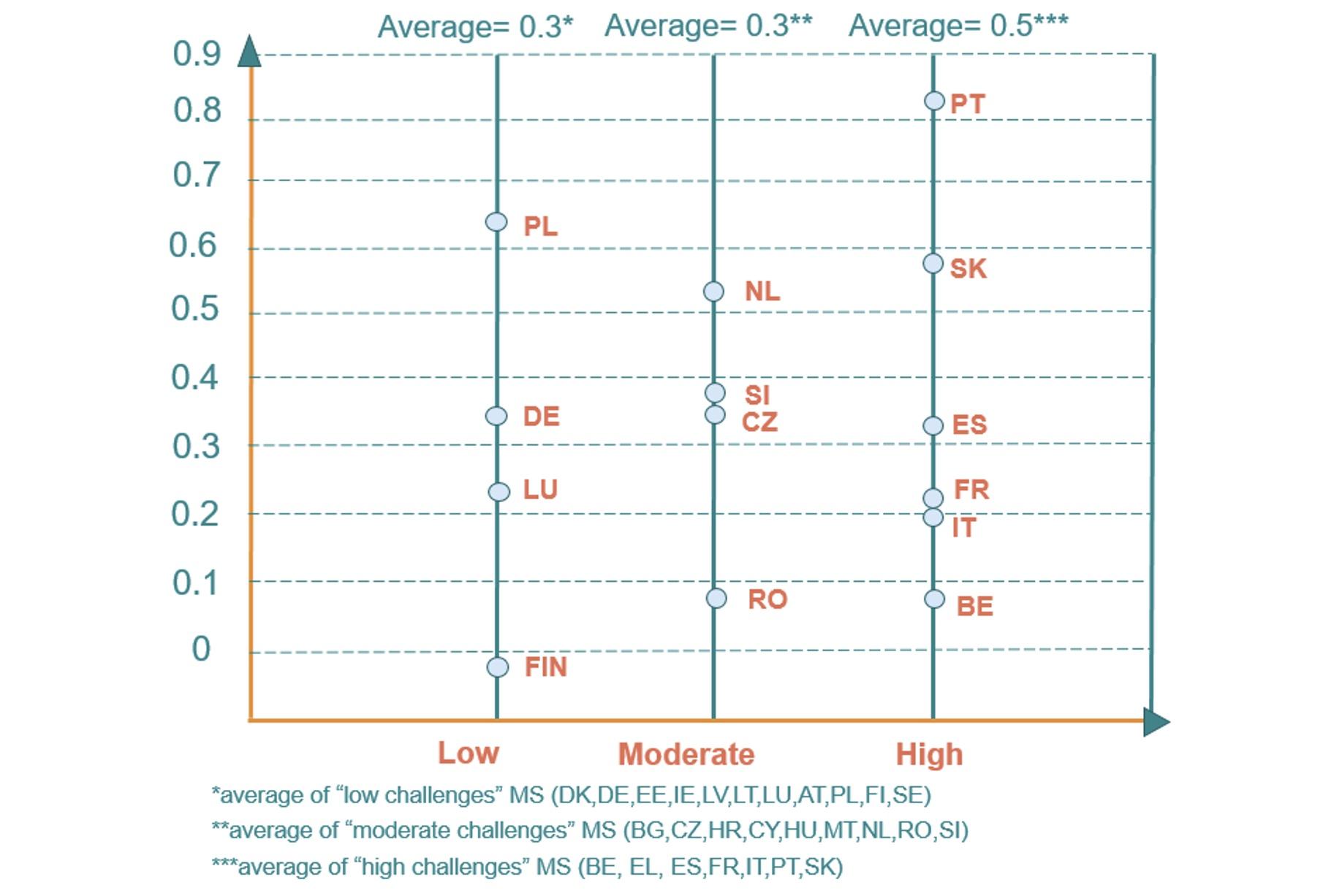

There are two main elements to prevent ‘bilateralism’. First, the Commission will operate within a common EU framework consisting in common requirements that the fiscal adjustment path of a Member State should respect. It is important to stress that, while being common, these requirements would be differentiated on the basis of the Member States’ debt sustainability challenges, which is a major improvement compared to the current system where the requirements and efforts delivered did not sufficiently reflect the actual fiscal consolidation needs. Moreover, there would be common criteria to assess reforms and investment commitments. Second, the role of the Commission ends with its assessment, while the decision on whether to endorse the plans or not lies with the Council, which is a more direct role than the opinion and recommendations by the Council for Stability and Convergence Programmes in the current setting. What the Commission proposes is therefore likely to stimulate the engagement of other Member States and improve the peer review of Member States’ policy plans, including the underlying fiscal and structural policy issues that determine overall public debt sustainability challenges. Gradual and sustained debt reduction is needed, and this will require more fiscal prudence going forward, but as experience shows fiscal consolidation efforts are in themselves not sufficient to ensure a low debt sustainability risk position (see Figure 1).

Figure 1 Debt sustainability challenge and average past fiscal effort (2011-19), selected countries, simple average

Note: The fiscal effort is measured as the annual change in the structural budget balance. The debt sustainability challenge is based on the Commission spring forecast 2022

Source: European Commission

Still based on the previous criticism, the Commission could also be perceived as too intrusive when it comes to assessing whether reforms and investment are good enough to justify a more gradual adjustment path. This objection is misplaced because it is up to the Member States to identify a set of reforms and investment that could underpin a more gradual adjustment. In fact, the suggested approach takes inspiration from the existing structural reform and investment clauses, whereby it is for the Member State to commit and provide solid evidence of their beneficial impact, but would make the criteria clearer: the set of reforms and investments should support growth and debt sustainability (in line with the country-specific recommendations as part of the EU Semester); should respond to common EU priorities; and should be sufficiently detailed, frontloaded, time-bound and verifiable.

An objection pertains to the role of the reference paths to be put forward by the Commission at the outset of the process, which could be seen as undermining political ownership by Member States of their fiscal adjustment strategies. The reference paths should not be seen as quantitative minimum requirements computed and imposed by the Commission. Nor they should be seen as providing a maximum fiscal effort. They are, instead, a practical translation of the common requirements that is meant to provide concrete guidance to Member States before they prepare and submit their own plans. To strengthen the common EU framework and the accountability of the Commission when assessing the plans, the methodology for determining these reference paths would be fully transparent and would be made public.

Finally, the Commission intends to strengthen the role of the independent national fiscal councils which were created via a directive on national fiscal frameworks. These institutions will play a greater role in assessing the assumptions underlying the plans, providing an assessment on the adequacy of the plans with respect to the debt sustainability and the country-specific medium-term goals, and monitoring compliance with the plans.

Technical criticisms

One recurrent objection refers to the complexity and lack of transparency that the use of debt sustainability analysis (DSA) would bring to the framework (Wyplosz 2022). The DSA is a well-known and well-documented methodology that is already widely used by international and national institutions to determine the risks associated to the debt trajectory (European Commission 2022, International Monetary Fund 2021). Hence, it allows to focus not only on the debt levels but also on the dynamics and risks. In the Commission proposals, this toolkit is set to play a role only at the very beginning of the process, i.e. in the identification of the sustainability challenges and the design and assessment of the adjustment path that Member States would put forward as part of their plan. Once the plan is endorsed by the Council, the focus shifts to monitoring compliance with the endorsed path and assessing any deviations from it, over the four years when the plan is binding.

Another objection concerns the fiscal indicator used to set the fiscal path and monitor compliance, i.e. primary expenditure net of discretionary revenue measures and cyclical unemployment spending. Some claim that the structural balance is simpler, well known, and, contrary to net expenditure ceilings, it does not impose any limits to the size of the government sector in the economy. Such criticisms are misplaced. An indicator based on net primary expenditure is under the direct control of the government, while allowing revenues to fluctuate in line with cyclical conditions. Hence, it is not only more observable than the structural balance, but it is also more counter-cyclical. Moreover, this indicator would be net of new discretionary revenue measures, so it is neutral vis à vis the public sector share in the economy: a government can decide to increase public spending as long as appropriate financing is found.

Economic criticisms

The economic criticisms mainly pertain to the fiscal rigidity implied by the reformed rules, the implications of not having changed the Treaty’s reference values, the limited incentives to improve the quality of public finances, and the absence of a central fiscal capacity.

The Commission orientations envisage that Member States’ plans should be binding for at least four years, which could be considered too rigid by some. Not only can legislations terminate before their natural lifespan but economic conditions may change significantly, warranting an update of the plan. The Commission proposal is justified by the need to avoid setting opportunistic behaviour by governments leading to backloading the adjustment effort. Frequent revisions would undermine the credibility of the plans as an anchor for prudent policies. This is balanced by the possibility to reopen the plan in the event of objective circumstances that make compliance with the plan impossible. While any change of government will not be a reason per se to change the plan, new elections could be one such circumstance leading to a new medium-term plan to be proposed. It would have to undergo the same validation process. The General Escape Clause (allowing suspension of the rules under severe shocks, as was done at the outset of the pandemic) would also continue to exist to cater for severe economic downturns, together with a country-specific clause for exceptional circumstances at country level.

Some have remarked that not having changed the 3% and 60% reference values for deficit and debt would impose a persistent deflationary bias on the economy. The Commission decided not to call into question the reference values enshrined in a Protocol annexed to the Treaty, which would have required cumbersome and politically controversial ratification procedures. Moreover, the 3% reference value for the budget deficit has acquired a useful public visibility and ‘magnetic power’ (Buti and Gaspar 2021). In addition, the net expenditure path would be designed to allow public debt to continue to decrease beyond the time frame of the fiscal-structural plans (four to seven years) without further fiscal restrictions.

Finally, some observers have criticised the absence of a central fiscal capacity in the Commission proposals, despite such reform having been put forward by international organisations and many economists during the public consultation on the economic governance review. More specifically, while the revised framework takes inspiration from NextGenerationEU in allowing Member States to put forward their own commitments, it does not provide for new common resources, which limits the incentives for Member States to abide to their commitments (Bordignon 2022). In the view of the authors, these observations are well taken: a well-designed central fiscal capacity could help rebalance the policy mix and, if focusing on supply-side oriented European public goods, could help tame the current inflation burst (Buti and Messori 2022). However, one has to acknowledge that establishing a central fiscal capacity remains politically controversial, so putting it forward as part of the governance reform could have overcharged the boat and made it more difficult to find agreement.

Conclusion

It has been encouraging to observe how the Commission orientations have triggered a renewed debate about reforming Europe’s economic governance. Recognising that institutional, technical, and economic issues are all part of striking a balance for the future governance framework, it is only fair that economists and policymakers raise critical questions. We hope to have answered to several of the criticisms put forward.

At the same time, it is now time to move from debate to decisions. We welcome that the ongoing discussions with Member States generally recognise that the Commission orientations are a reasonable and coherent basis for making progress towards a common landing zone. Swift agreement on revising the EU fiscal rules and other elements of the economic governance framework is a pressing priority. Considering the mounting challenges that the EU is facing, there is a need for strong policy coordination and effective surveillance. We should therefore reach a consensus on reform of the economic governance framework ahead of Member States’ budgetary processes for 2024. This has also been recognised by the Member States of the euro area in their call for swift progress on the review as a priority for enhancing economic policy coordination (Eurogroup 2022).

A thorough reform of the EU economic governance framework would require legislative change. Amending the underlying legislation would allow for clarification and simplification of the framework. It would provide a high degree of legal certainty for how a reformed framework would operate, with the involvement of the Council and the European Parliament. Based on the ongoing discussion, the Commission will consider tabling legislative proposals.

Authors note: The authors write in their personal capacity.

References

Blanchard, O, A Sapir and J Zettelmeyer (2022), “The European Commission’s fiscal rules proposal: a bold plan with flaws that can be fixed”, Bruegel Blog post, 30 November.

Bordignon, M (2022), “Europa: ecco le nuove regole fiscali”, LaVoce.info, 15 November.

Buti, M and V Gaspar (2021), “Maastricht values”, VoxEU.org, 8 July.

Buti, M, J Friis and R Torre (2022), “How to make the EU fiscal framework fit for the challenges of this decade”, VoxEU.org, 10 November.

Buti, M and M Messori (2022), “A central fiscal capacity to tackle stagflation”, VoxEU.org, 3 October.

Eurogroup (2022) “Eurogroup statement on draft budgetary plans for 2023”, 5 December.

European Commission (2022) “Fiscal Sustainability Report 2021”, Institutional Paper 171, 25 April.

European Commission (2022) “Communication on orientations for a reform of the EU economic governance framework”, COM(2022) 583 final.

International Monetary Fund (2021) “Review of The Debt Sustainability Framework For Market Access Countries”, Policy Paper No. 2021/003, 3 February.

Lorenzoni, G, F Giavazzi, V Guerreri and L D’Amico (2023), “New EU fiscal rules and governance challenges”, VoxEU.org, 2 January.

Wyplosz, C (2022) “Reform of the Stability and Growth Pact: The Commission’s proposal could be a missed opportunity”, VoxEU.org, 17 November.