Most firms organise production around teams of workers, which invariably bring together workers with varying abilities and skills. If the team succeeds in meeting its goals, it is normal to reward all members, often automatically through a boost in pay proportionate to team production, or through a bonus for meeting a target threshold or at least shared praise for the group. While teams invariably combine higher and lower-ability workers, analyses of teams in business settings often focus on the top performers (Bandiera et al. 2013, Hamilton et al. 2003, Lazear 2000). Little attention has been given to the behaviour of lower-skilled team members, even as the ongoing growth of inequality in rewards has the potential to discourage them and reduce team success.

To see how lower-ability workers respond to team incentives, we conducted a real-effort experiment in which team members performed independent tasks with identifiable productivity but pay that depends on team performance (Freeman et al. 2022). We give participants in the experiment the real-effort slider task (Gill and Prowse 2012). They face a computer screen displaying 48 sliders, each on a scale from zero to 100, and use the mouse to move as many sliders as they can from the initial position zero to exactly the middle point 50 in the allotted time. Each person completes the task separately but is paid based on team output.

While workplace teams are often organised around a technology of work that links what workers do into a seamless whole, firms also create team-related rewards for workers who do their jobs independently, as shown for cashiers (Mas and Moretti 2009), fruit pickers (Bandiera et al. 2013) or garment factory workers (Hamilton et al. 2003). Firms add a team component even to piece-rate pay to give workers an incentive to share knowledge or to help other workers deal with problems that adversely affect total output.

Random assignment to teams and payment systems

Our experiment recruited 248 students from Zhejiang University to work in randomly grouped teams of two in which each team member does the real effort slider task

independently under different payment systems. Both the random assignment and the independent nature of the slider task eliminate any personal ties from within the group. Werandomly assigned the teams into one of the three distribution schemes: equal pay, where they shared equally the total payment; piece-rate, where each received their payment proportional to their own production per the actual task; andwinner-takes-all, where the participant who produced the most got the total payment. To complete the design, we randomly assigned some teams to a productivity threshold condition that compensates members only if team output reaches or exceeds a specified threshold while others faced no threshold condition.

A group target threshold and other non-linear incentives have been shown to promote worker productivity (Freeman et al. 2019).

What might one expect from the payment systems? A reasonable expectation is that piece-rate would generate high output because it treats each person ‘fairly’ given the independent work task. But some might expect winner-takes-all to do well because the all-or-nothing incentive could induce extraordinary effort from both members in a team. We expected equal sharing would suffer because it is likely to create free riding, as participants could benefit from their partner’s output and risk losing part of what they produced to a free rider.

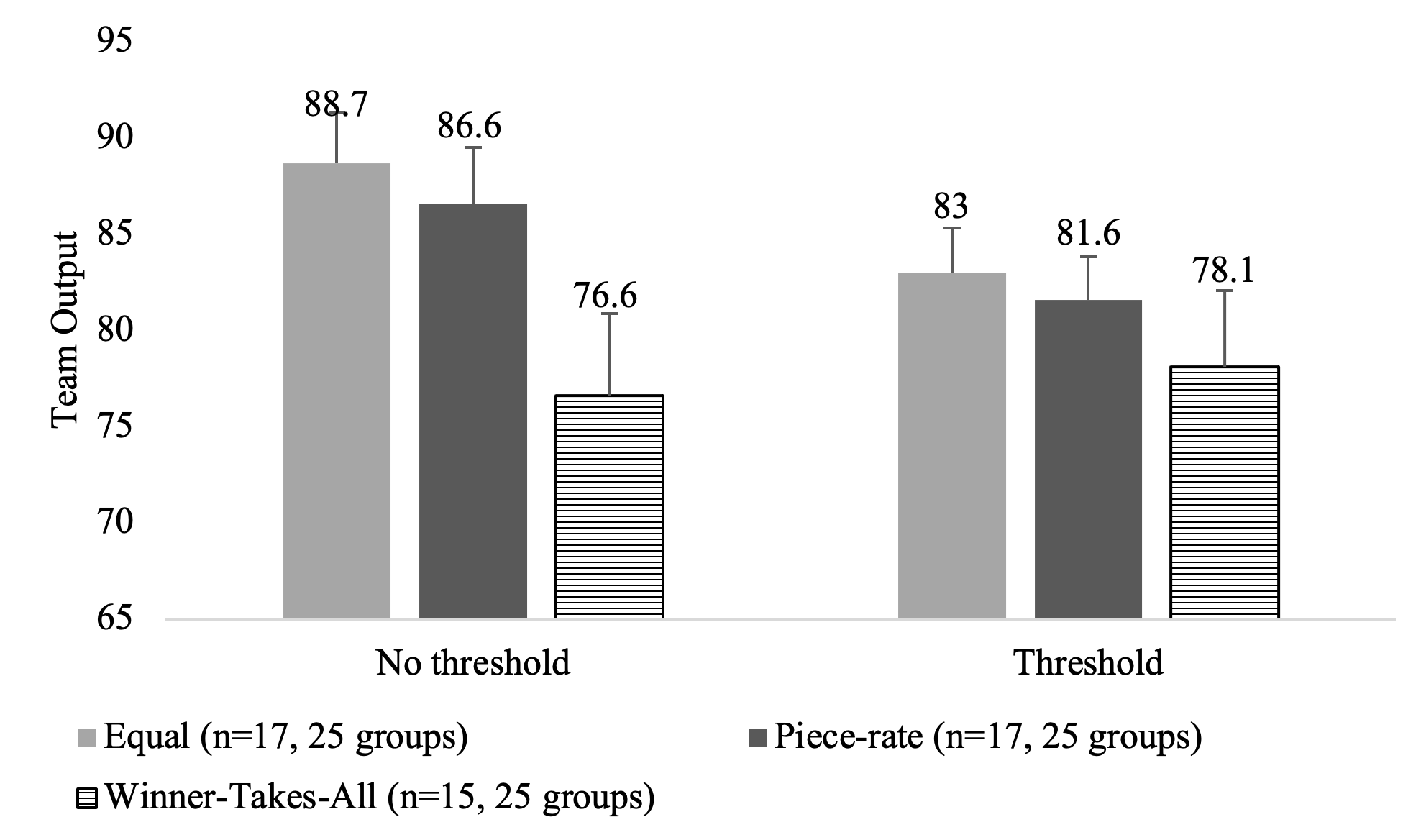

Figure 1 shows that the random assigned experiment yielded a very different pattern: teams assigned to equalsharing outperformed winner-takes-all teams substantially and outperformed those assigned piece-rate by smaller, statistically insignificant amounts.

Comparing the number of completed slides reveals that equal sharing sparked the lower-ability participants to produce substantially more than lower-ability participants in winner-takes-all, and insignificantly higher output than those in piece-rate, while having little or no effect on higher-ability participants across distribution schemes.

Figure 1 Average team productivity across team incentives

We asked participants in a second part of the experiment whether they wanted to continue with their randomly assigned distribution scheme or if they both would agree to switch to a different scheme. If team members disagreed, the status quo mode of payment would remain. We asked team members to discuss what they should do in an online chat room, which we recorded to gain insight into their thinking. Two aspects of the discussions stood out.

- First, discussions among teams facing a threshold made it clear to both members that the only way to meet or surpass it was to cooperate on a high-effort outcome. High-ability persons were more willing to choose an equaldistribution in this setting than those without a team threshold: 35% of teams chose equal sharing when faced with a threshold compared to 16% of teams without a threshold. Nine of the ten teams in which a higher-ability participant favoured equal sharing were in the threshold condition.

- Second, discussions often generated what seems to be a social norm favouring piece-rate, with all members – including those with lower ability – recognising some moral value to having individual earnings proportionate to individual output. When the team began with a winner-takes-all compensation, which had the worst performance in the random assignment experiment, lower-ability participants either proposed to switch to the piece-rate or committed to work harder if their team choose equal sharing.

The last stage of the experiment had participants perform the slider task with the distribution scheme they chose after discussion. Surprisingly, teams that were assigned equal sharing in the initial random assignment had higher outcomes in the last stage, just as they did in the first stage, and for the same reason: the better performance of the lower-ability participants. We did not expect this and did not build in any probing of the pattern. It raises the possibility that a person’s early experience of a compensation system (or any other aspect of work) may affect their productivity in later work situations.

Interpreting the results: Guilt aversion?

So why did lower-ability persons devote extra effort to raise their productivity under equal sharing? The best explanation we can offer is that they sought to avoid being the weak link that produces team failure (Charness and Dufwenberg 2006). That equal sharing did not reduce the effort of the more able may reflect their desire to maintain their ranking in the team. Before the experiment, we did not conjecture guilt aversion as a major factor in team behaviour, but now we appreciate its potential importance and the value of modelling it in different ways, such as Gill and Stone’s (2014) model that suggests lower-ability workers who think they deserve less than the equal share in a team are motivated to match the higher-ability workers’ output. Our guilt aversion and their inequality aversion interpretation differ from extant analyses of lower-ability workers that attribute productivity levels to social factors such as working with friends (e.g. Bandiera et al. 2010) or mutually monitoring each other (e.g. Bandiera et al. 2005).

Whether our experiment generalises to more complicated real-world situations is unclear. Our use of randomisation of two-person teams, assignment of compensation systems and of thresholds, and the ease of learning the slider task and being able to judge the relative ability of team members potentially strengthened the role of guilt aversion incentives compared to what it would be in teams with larger numbers (where free-riding incentives may dominate) and in more complex tasks. For instance, a recent work by Frederiksen et al. (2022) studied the production environment with interdependent work.

More experimentation in different settings is needed to assess the extent to which our findings generalise to situations beyond those captured by our experiment. The broadest implication for further research on teams and for managements choosing forms of compensation in team settings is to be attentive to the performance of lower-ability persons, whose responsiveness to sharing in rewards can be critical to team performance.

References

Bandiera, O, I Barankay and I Rasul (2010), “Social incentives in the workplace”, The Review of Economic Studies 77(2): 417–458.

Bandiera, O, I Barankay and I Rasul (2013), “Team Incentives: Evidence from a Firm Level Experiment”, Journal of the European Economic Association 11(5): 1079–1114.

Charness, G and M Dufwenberg (2006), “Promises and Partnership”, Econometrica 74(6): 1579–1601.

Freeman, R, X Pan, X Yang and M Ye (2022), “Team Incentives and Lower Ability Workers: An Experimental Study on Real-Effort Tasks”, NBER working paper 30427.

Freeman, R, W Huang and T Li (2019), “Non-linear Incentives Improve Worker Productivity and Earnings”, VoxEU.org, 7 May.

Gill, D and V Prowse (2012), “A Structural Analysis of Disappointment Aversion in a Real Effort Competition”, American Economic Review 102(1): 469–503.

Hamilton, B H, J A Nickerson and H Owan (2003), “Team Incentives and Worker Heterogeneity: An Empirical Analysis of the Impact of Teams on Productivity and Participation”, Journal of Political Economy 111(3): 465–497.

Lazear, E P (2000), “The Power of Incentives”, American Economic Review 90(2): 410–414.

Manchester, C, A Frederiksen and D Hansen (2022), “How group-based incentives increase worker performance”, VoxEU.org, 18 August.

Mas, A and E Moretti (2009), “Peers at Work”, American Economic Review 99(1): 112–45.

Gill, D and R Stone (2015), “Desert and inequity aversion in teams”, Journal of Public Economics 123: 42–54.

Tonin, M and M Vlassopoulos (2012), “Do social incentives matter? Evidence from an online real effort experiment”, VoxEU.org, 26 July.