“The policy of European integration is a matter of war and peace in the 21st century.”

Helmut Kohl, Speech at Catholic University, Leuven, 2 February 1996.

"We can never forget what Jacques Delors said before the introduction of the euro. We need a political union; a currency union alone will not suffice. We have taken some steps forward, but we have not made sufficient progress. That is perfectly evident. This means that there needs to be more, rather than less, integration.” German Chancellor Angela Merkel, Responding to questions in the Bundestag, 13 May 2020 (authors’ translation).

The founders of the euro viewed the common currency’s role as a foundation for European peace and prosperity (see the opening quotes). Yet, they knew big challenges lay ahead. For years before the start of the monetary union in 1999, economists had warned that the member states of the EU do not constitute an ‘optimum currency area’ (Friedman 1997). This means that a single policy interest rate might exacerbate, rather than mitigate, economic differences, creating severe strains among euro area countries.

Since the euro’s beginning, European leaders believed that as tensions arose, member states would choose to form a closer union—integrating their economies and financial systems, sharing burdens and risks. To a considerable extent, experience has borne out these hopes. And yet, over the past two decades, there has been only a grudging, crisis-driven progress toward a truly resilient monetary union. Politically and financially, the euro area remains divided. The COVID-19 pandemic brings renewed tensions. With it comes a harsh reminder that standing still is simply not an option.

In this column, we review the progress toward completion of the European monetary union and highlight key gaps that remain. We do this by comparing the euro area and the US. Our focus is on risk sharing, banking and capital markets union, and labour mobility. In each case, the euro area remains significantly less developed than the US. As a result, shocks to euro area member states still cause larger economic and financial dislocations.

Risk sharing in a monetary union

While it has risen over the two decades of monetary union, risk sharing among the member states of the euro area remains well below that in the US. The progress reflects the hopes of the Kohl- Mitterand generation, but the gaps still make Europe’s monetary union vulnerable.

Risk sharing is the simple idea that a group shares the pain of a shock that hits some households and not others. In the absence of risk sharing, consumption losses are borne solely by those directly affected by the shock. By contrast, complete risk sharing means that the per capita consumption losses are borne equally.

Recent research highlights the changing gap between the two monetary unions in the extent of risk sharing. Over the period 1999-2016, 60% to 80% of a US state-specific shock was ‘smoothed’ by efforts to insure consumption across state lines (Cimadomo et al. 2018). In contrast, in the period 2001-2017, risk sharing in the euro area started at about 33%, and rose following the euro area crisis of 2010-2012 to about 56% (see Cimadomo et al. 2020).

Consumption smoothing comes through both public and private mechanisms. In the US, federal fiscal transfers—reflecting automatic stabilisers including progressive income taxation and unemployment insurance—absorb an estimated 10%-15% of state-specific shocks. Most of the smoothing occurs through ‘private channels’: borrowing that is not solely reliant on local credit supply and income flows arising from cross-border portfolio diversification. In the euro area, prior to the 2010-2012 European financial crisis, virtually all smoothing came through private channels. Since then, official financial assistance directed explicitly at risk sharing between core and peripheral euro area countries grew noticeably.

However, there remains no common fiscal policy to provide either automatic or discretionary transfers across the euro area in response to regional shocks. Moreover, official financial assistance comes in the form of loans, not outright expenditure. For example, the European Stability Mechanism (ESM, established in 2012) has total capacity to lend up to €500 billion, or about 4% of euro area GDP. However, such loans add to what are already substantial sovereign debt burdens. In addition, ESM credit may come with requirements for fiscal austerity that can aggravate—rather than smooth—adverse shocks.

Table 1 Two monetary unions: US and euro area

Source: Authors.

Banking and capital market union

If most cross-border risk sharing in a monetary union occurs through private means, then the resilience of the financial system is critical for sustainability. This brings us to the financial trilemma: financial integration in a monetary union—where credit and capital flow freely across borders—depends on cross-border regulatory coordination (Cecchetti and Schoenholtz 2017). Otherwise, country-specific shocks can cause runs as investors come to doubt that a unit of currency will have the same value in every jurisdiction. Concerns that a euro in an Italian or Spanish bank may be worth less than one in a German or Dutch bank can lead depositors to shift funds across national boundaries, fragmenting the financial system.

What kind of coordination can ensure the system remains intact? Since the euro area is bank-centric, attention has focused on the development of a banking union—involving common regulation and supervision, a common resolution mechanism, and a common deposit insurance scheme. When the euro area crisis peaked in 2012, none of these elements were in place. Not surprisingly, we witnessed sizable runs out of banks in the periphery (especially Italy and Spain), toward banks in the core (notably Germany and the Netherlands). The 2011-2012 surge in the Eurosystem’s TARGET2 balances provides a quantitative measure of these runs (Cecchetti and Schoenholtz 2014a).

As supporters of the euro surely hoped, the crisis prompted notable reform. As of 2014, the Single Supervisory Mechanism authorises the ECB to license and supervise all banks in the euro area, and to set regulatory requirements to make banks resilient. In practice, the ECB directly supervises more than 100 banks that hold over 80% of the banking system assets in the monetary union. The Single Resolution Mechanism (SRM)—backed by contributions from banks to the Single Resolution Fund (SRF)—has the task of restructuring insolvent banks. In addition, ESM loans to countries can be used to recapitalise banks.

However, reforms have gone only so far. Based on both accounting and market-based measures, the largest euro area banks remain significantly less well-capitalised than their US counterparts. Furthermore, funding for the SRF (€33 billion as of July 2019) remains only a tiny fraction of the €34.6 trillion in total banking system assets (as of March 2020). Third, and perhaps most important, there remains no common deposit insurance scheme across the euro area (see Table 1).

On top of this, euro area capital markets remain highly fragmented, with only a few large and liquid national markets. Moreover, in contrast with the US, there is no truly safe asset other than Eurosystem reserves: even core countries cannot impose an obligation on the independent ECB to accept their sovereign debt as collateral should their fiscal health deteriorate.

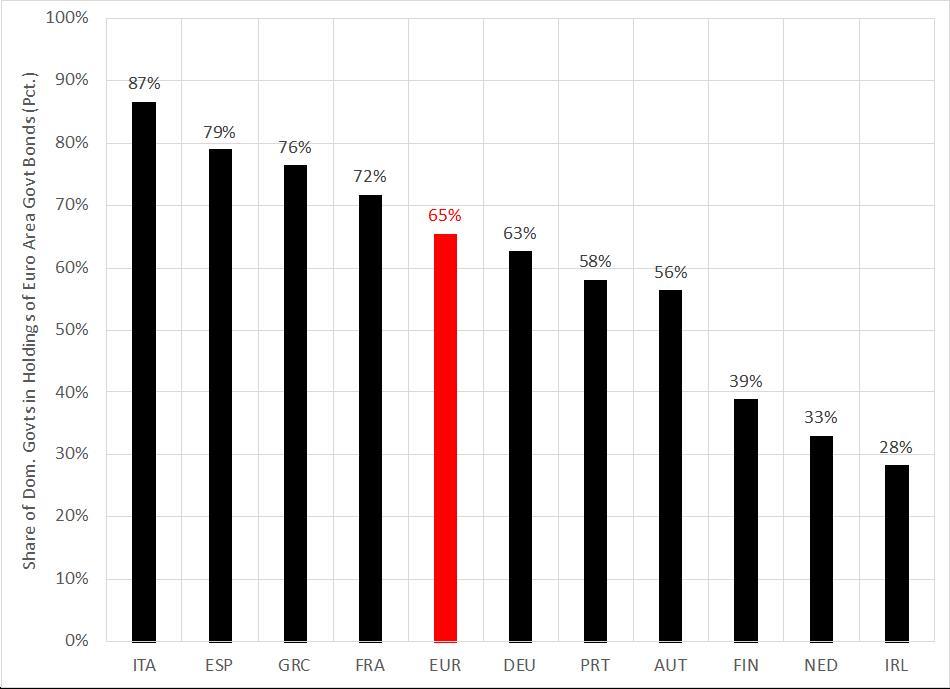

In this environment, euro area regulations and practices—like the equal treatment of all sovereign debt in the computation of capital requirements or the limited differentiation in the haircuts in the ECB’s collateral framework— encourage banks to continue to hold primarily their home country’s debt as their safe asset (see chart below). This enormous home bias serves to reinforce the ‘doom loop’ linking banks to their sovereigns within the euro area—a problem that does not exist for large banks in the US (Cecchetti and Schoenholtz 2014b).1

Figure 1 Euro area banks’ holdings of domestic government debt as a share of euro area government debt held (percent), March 2020

Source: ECB Statistical Data Warehouse.

The role of labour mobility

Beyond fiscal transfers and financial arrangements, the movement of labour can also help distribute the impact of a local shock. When something creates relatively high unemployment in one jurisdiction, people can move to find work in places that are less affected. So, labour mobility is yet another way to share pain.

The four freedoms of the EU are the free movement of people, goods, services, and capital across borders. To facilitate cross-border labour mobility, there are mechanisms like the coordination of social security schemes. Furthermore, it appears that cross-border mobility has picked up over time (Arpaia et al. 2016). And, there is evidence that immigrants to the euro area—who have roughly doubled since 1999 to 9% of the population—are more mobile than those locally born (Basso et al. 2019b).

Nevertheless, people are substantially less mobile in Europe than they are in the US. So, for example, while estimates are that 8% of the population of a US state leaves following a 10% decline in employment, only 2% would leave the euro area member state in the aftermath of a similar-sized disruption (Basso et al. 2019a). Consequently, shocks lead to wider and more persistent dispersion of unemployment in the euro area: for example, the standard deviation of unemployment rates across euro area states was three times higher at the peak of the euro area crisis than it was in the US at the peak of the 2007-2009 crisis (see Table 1).

The impact of COVID-19

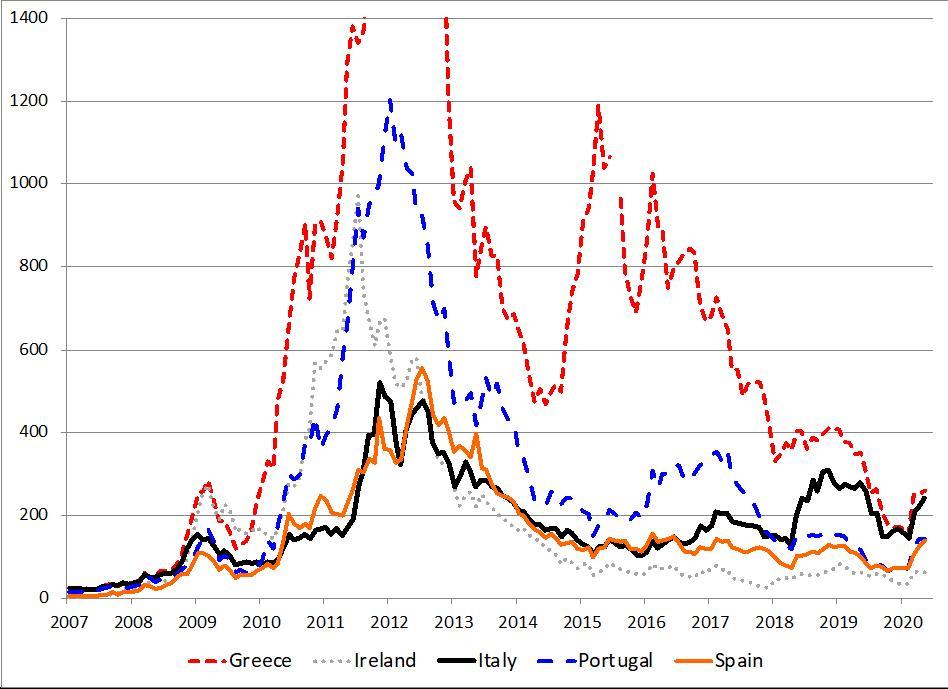

This brings us to the current crisis. COVID-19 is surely the largest shock to the euro area economy since the euro began in 1999 (and probably the biggest since the end of WWII). Yet, looking at bond yield spreads versus Germany—a standard thermometer for taking the temperature of euro area tensions—the current disruptions remain modest compared to the crisis of 2010-2012 (see Figure 2). In part, this reflects that the shock has hit all member states hard. However, the virus also has had a differential impact, with more severe dislocations in Italy and Spain than elsewhere. So, the limited deterioration reflects well on the improved resiliency of euro area institutions, as well as on investor confidence in the willingness of the ECB again to do “whatever it takes” to sustain the euro.

Figure 2 Euro area bond yield spreads over Germany (basis points), 2008-May 2020

Source: Eurostat and Financial Times.

At the same time, however, the relative lack of tensions may reflect expectations of further cross-border risk sharing, especially in the form of fiscal transfers. As the Maastricht Treaty signatories hoped, it is precisely during and in the wake of a crisis that risk sharing increases. As our narrative highlights, we see that most clearly in developments like the progress toward banking union.

In addition, it is difficult to imagine a crisis that would provide greater incentive for risk sharing than the current one. Battling COVID-19 is a powerful, common goal not only in the euro area, but across the entire planet. Everyone knows that viruses do not recognise borders. At the same time, less indebted countries remain concerned that any increase in risk sharing will diminish the incentive for the highly indebted member states to improve their fiscal health ahead of a future crisis.

Ultimately, sustained popular support for the euro (still widely evident in 2019 surveys, see European Commission 2019) probably depends in part on the perception of ‘solidarity’—the willingness to share risks—when a common, euro area-wide shock like COVID hits. So, while such solidarity has always been grudging, it seems reasonable in this crisis to expect another upward ratchet in euro area risk sharing.

As Chancellor Merkel’s quoted comments imply, the future of the euro depends on a willingness to integrate more, and soon.

Authors’ Note: An earlier version of this post appeared on www.moneyandbanking.com.

References

Arpaia, A, A Kiss, B Palvolgyi and A Turrini (2016), "Labour mobility and labour market adjustment in the EU", IZA Journal of Migration and Development 5(1).

Basso, G, F D’Amuri and G Peri (2019a), “Labour mobility and adjustment to shocks in the euro area: The role of immigrants”, VoxEU.org, 13 February.

Basso, G, F D’Amuri and G Peri (2019b), "Immigrants, Labor Market Dynamics and Adjustment to Shocks in the Euro Area", IMF Economic Review 67(3): 528-572.

Cecchetti, S G and K L Schoenholtz (2014a), “Update on Target2 balances: limited progress”, www.moneyandbanking.com, 12 June.

Cecchetti, S G and K L Schoenholtz (2014b), “The Importance of Being Europe”, www.moneyandbanking.com, 27 October.

Cecchetti, S G and K L Schoenholtz (2017), “The Other Trilemma: Governing Global Finance”, www.moneyandbanking.com, 24 July.

Cimadomo, J, S Hauptmeier, A A Palazzo and A Popov (2018), "Risk sharing in the euro area", Economic Bulletin of the European Central Bank 3.

Cimadomo, J, G Ciminelli, O Furtuna and M Giuliodori (2020), "Private and public risk sharing in the euro area", European Economic Review 121.

European Commission (2019), “Standard Eurobarometer 92”.

Friedman, M (1997), “The Euro: Monetary Unity to Political Unity?”, Project Syndicate, 28 August.

Endnotes

1 While the Bank of America’s home jurisdiction is North Carolina, we assume it does not have a position in that state’s debt that is large relative to its capital.