The war in Ukraine has led to a sharp reduction in EU exports to Russia and Ukraine and higher prices for energy and commodities, which are squeezing profits. This column looks at European companies’ resilience and the risks to their future investment. Policy support played an important role in swiftly bringing corporate investment closer to pre-crisis trends following the pandemic, but the ongoing monetary policy tightening and the war in Ukraine have increased firms’ vulnerability and are likely to weaken investment. In this context, European policies need to remain well anchored towards the transformation of the European economy.

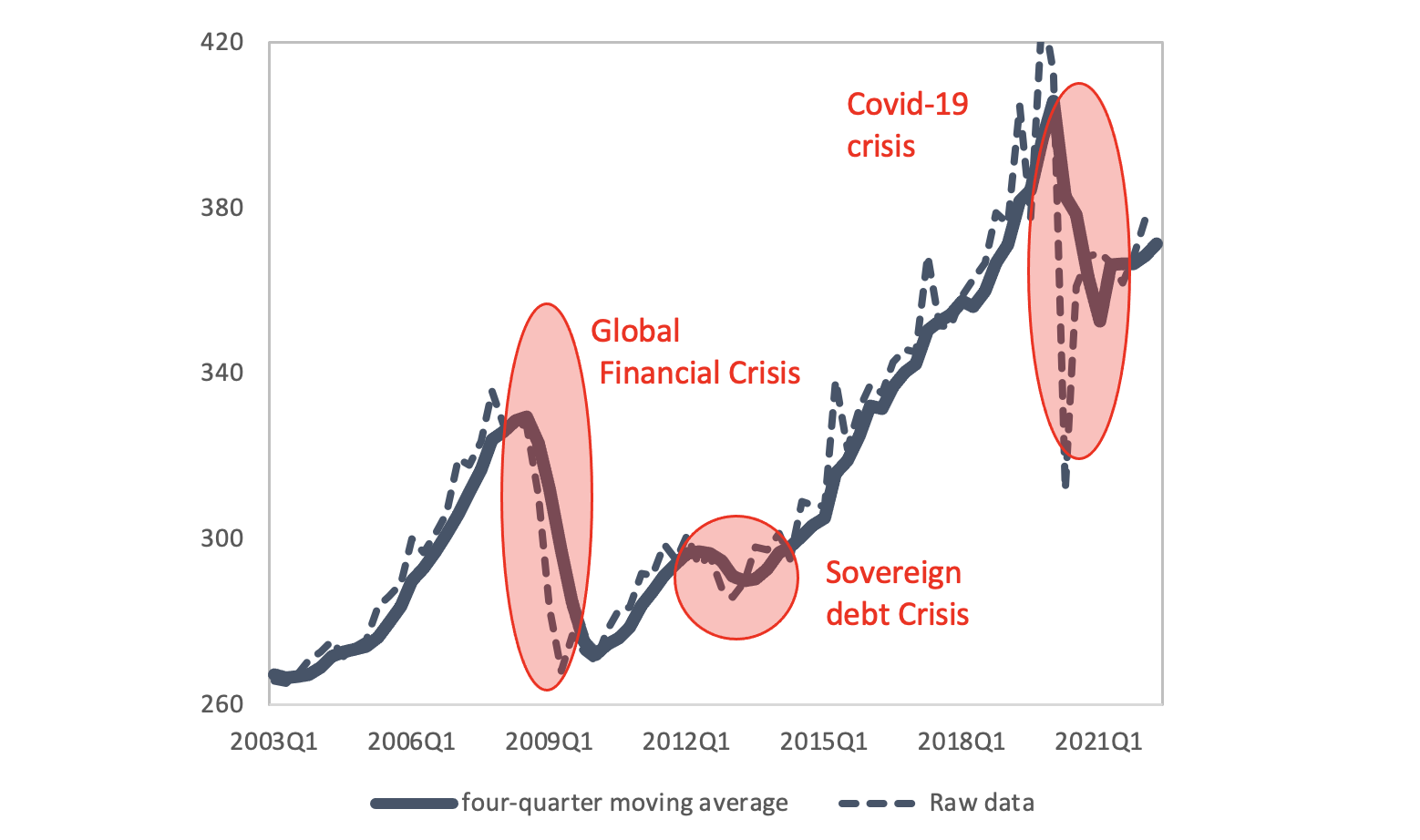

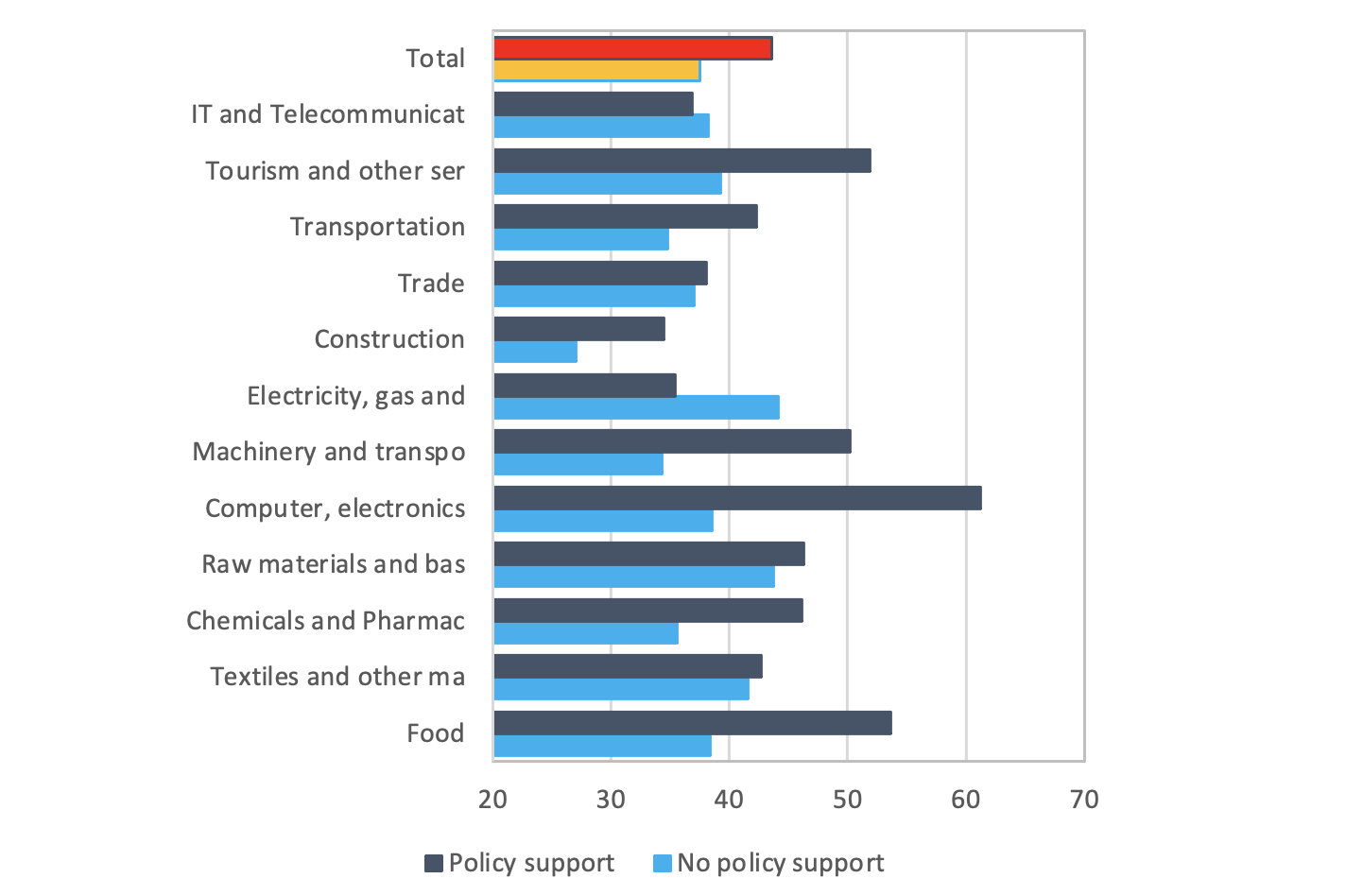

The recovery in corporate investment began in mid-2021, and it was still in full swing when the energy crisis hit (Figure 1). During the COVID-19 crisis, corporate investment pulled back sharply, declining to 13% below its pre-crisis level, a fall comparable to the global financial crisis. Investment then started to recover, but by the second quarter of 2022, in real terms, annual flows were still 6% below levels recorded pre-COVID-19, in 2019. The policy support deployed during the COVID-19 crisis was unprecedented and multifaceted. It enabled firms to navigate the COVID-19 crisis better than feared so that corporate investment reacted less to the collapse in economic activity than might have been expected. Figure 2 shows the share of firms expecting to accelerate investment in the different sectors of the European economy. In most areas, firms that benefited from policy support were more likely to accelerate investment than those in the same sector that did not receive support (Harasztosi et al. 2022).

Figure 1 Real corporate investment

Source: EIB estimates based on Eurostat data.

Figure 2 Share of firms accelerating investment

Source: EIB computations based on EIBIS 2022.

The much more challenging environment for firms

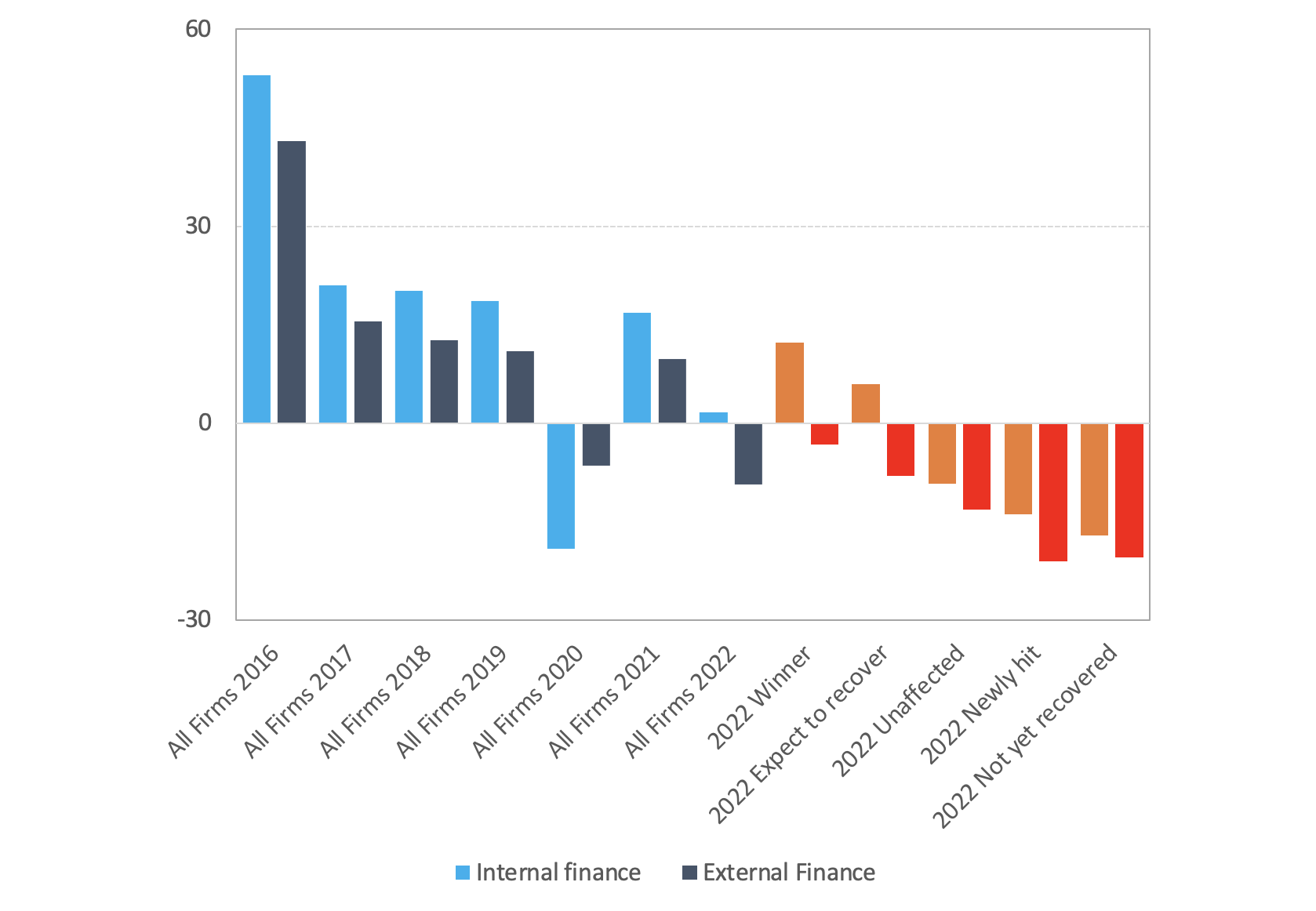

Before the Russian invasion of Ukraine, it was far from clear whether the strong recovery was self-sustained and uneven trends among sectors and types of firms were already materialising. Following the invasion, new types of vulnerability have emerged and economic forecasts have been revised downwards. Corporate investment faces major, interconnected headwinds. Chief among them are the harsh rise in borrowing costs and disruptions caused by the war in Ukraine, including the energy shock, huge uncertainty, and trade disruptions. In mid-2022, the cost of corporate borrowing began to rise abruptly, reflecting monetary tightening and rising bond yields. Risk spreads also widened, which is likely to affect firms that are more indebted following the pandemic. After years of low rates and abundant liquidity, investment ability to absorb higher borrowing costs is unknown. Indeed, looking forward, the EIBIS provides a bleak outlook for investment finance, especially external sources. Figure 3 shows firms’ expectations regarding the internal and external capacity to finance investments. Since 2016, firms have mostly been optimistic, with two exceptions — during the first year of the COVID-19 crisis, and during the last EIB Investment Survey (EIBIS) wave in 2022. At these points, the net balances leaned mostly towards a worsening situation. After seeing an improvement during the EIBIS 2021, firms now expect their financial resources to deteriorate. This is especially clear for external sources of finance.

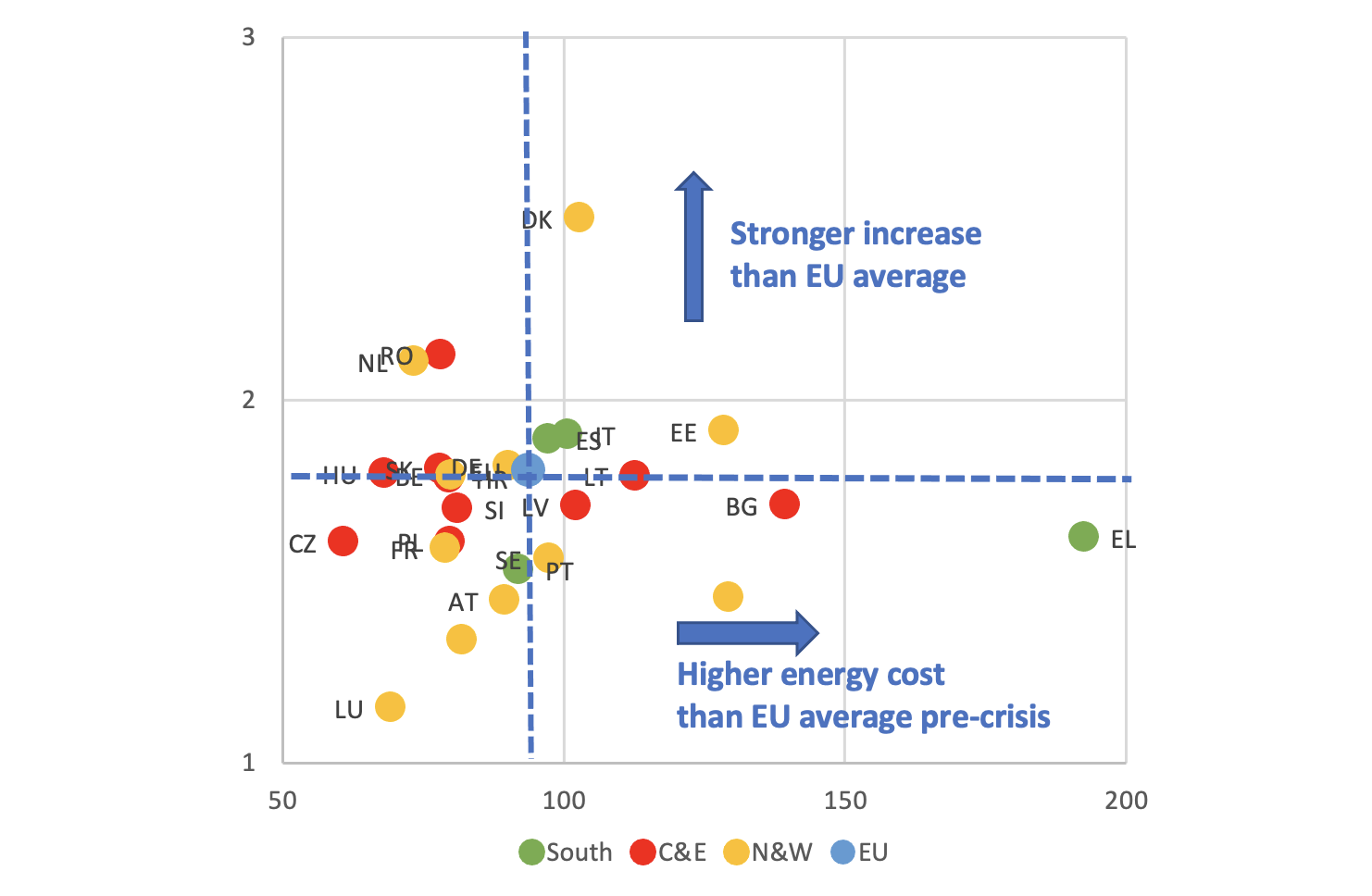

The war in Ukraine has destabilised EU firms. First, it has led to a sharp reduction in exports to Russia and Ukraine, curtailing sales in these markets. Second, higher prices for energy and commodities are squeezing profits. Rising energy costs have historically been associated with declines in firm profits and while EU energy dependence has declined, energy costs are still a major drag on companies’ margins. When energy prices reached record highs in 2012, which were nevertheless far below recent levels, firm profits declined dramatically. In the current crisis, the shock has spread unevenly among EU economies, due to differences in their export exposure, energy dependencies and energy mix (Zinglersen 2022). Countries suffer more if their energy dependency is tilted towards oil and gas. As shown in Figure 4, the same change in international energy prices (coal, gas, and oil) resulted in very different changes for companies in EU countries. Compared to 2021, firms’ energy prices have increased by 80% in the EU as a whole, ranging from a low of 10% in Luxembourg to a high of 140% in Denmark. Beside differences in the energy mix, other factors such as the period during which the energy price is fixed in the contractual agreement, taxes, regulation, transportation costs, and local margins play a role, too (Du Bella et al. 2022).

Figure 3 Expectations regarding investment finance

Source: EIB computations based on EIBIS 2016-2022.

Note: the categories winner (increasing each year), expected to recover, unaffected (remaining the same), newly hit and not yet recovered are based on company’s sales and turnover in 2020, 2021 and 2022 compared to pre-pandemic level in 2019.

Figure 4 Energy prices for European corporates: Pre-crisis level and change

Source: EIB calculations based on EUROSTAT, European Commission.

Note: X-axis is the price is euros per Mega-watt hour, in 2021H2 in euros. Y-axis is the price in 2022Q2 compared to the price in 2021. Red, green and orange indicate countries from Central and Eastern, Southern, and Western and Northern Europe respectively.

New sources of vulnerabilities likely to weaken firms’ investment

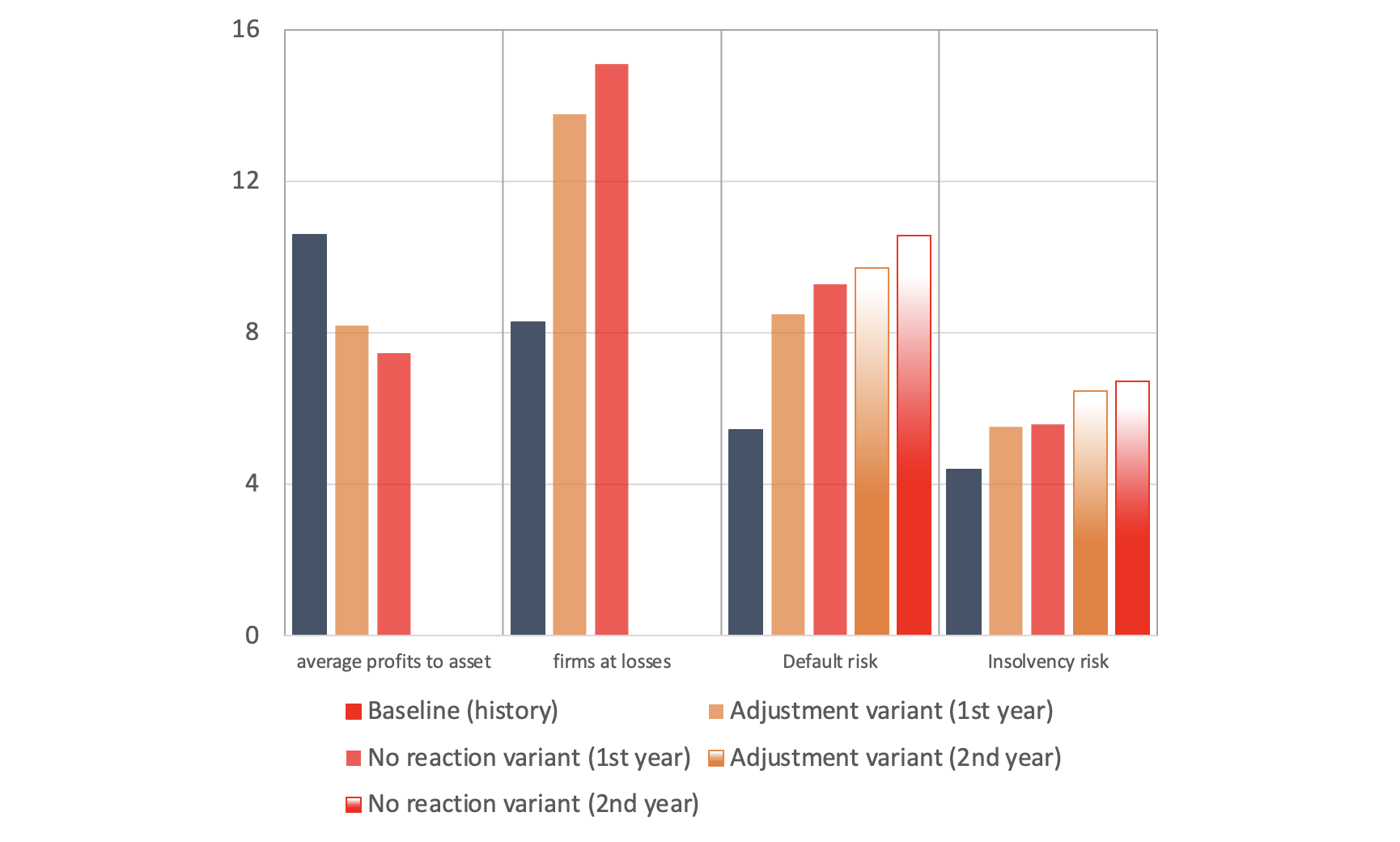

We simulate the change in profits resulting from the shock of an energy price increase and export decline by considering two possible scenarios. In the ‘no reaction’ case, it is assumed that besides a reduction in exports, demand is not affected by rising costs and selling prices are kept constant. Production is maintained and the energy shock is fully absorbed in companies’ profit margins. In the ‘adjustment’ case, part of the energy cost increase is passed on through higher selling prices, demand is reduced, and production follows suit. As production is reduced, certain costs – such as employment costs – decrease, but do not react fully (Maurin and Pál 2020). As shown in Figure 5, the impact is substantial. As firms’ reactions dampen the increase in vulnerabilities to some extent only, the impact is stronger than in the ‘no reaction’ case. From 11%, the return on assets of EU firms falls by 3 percentage points for the ‘adjustment’ case and 4 percentage points for the ‘no reaction’ case. The share of firms registering losses increases by 7 percentage points in the ‘no reaction’ case, almost doubling compared to normal times, and by 5 percentage points in the ‘adjustment’ case. The result varies among sectors, and is mainly driven by energy dependence (EIB 2023, Bialek et al. 2023). Energy needs are particularly high for chemicals and pharmaceuticals, transportation and raw materials – sectors for which energy dependence is around 12%. Conversely, IT and telecommunications, construction, services, and trade are less reliant on energy and therefore less affected.

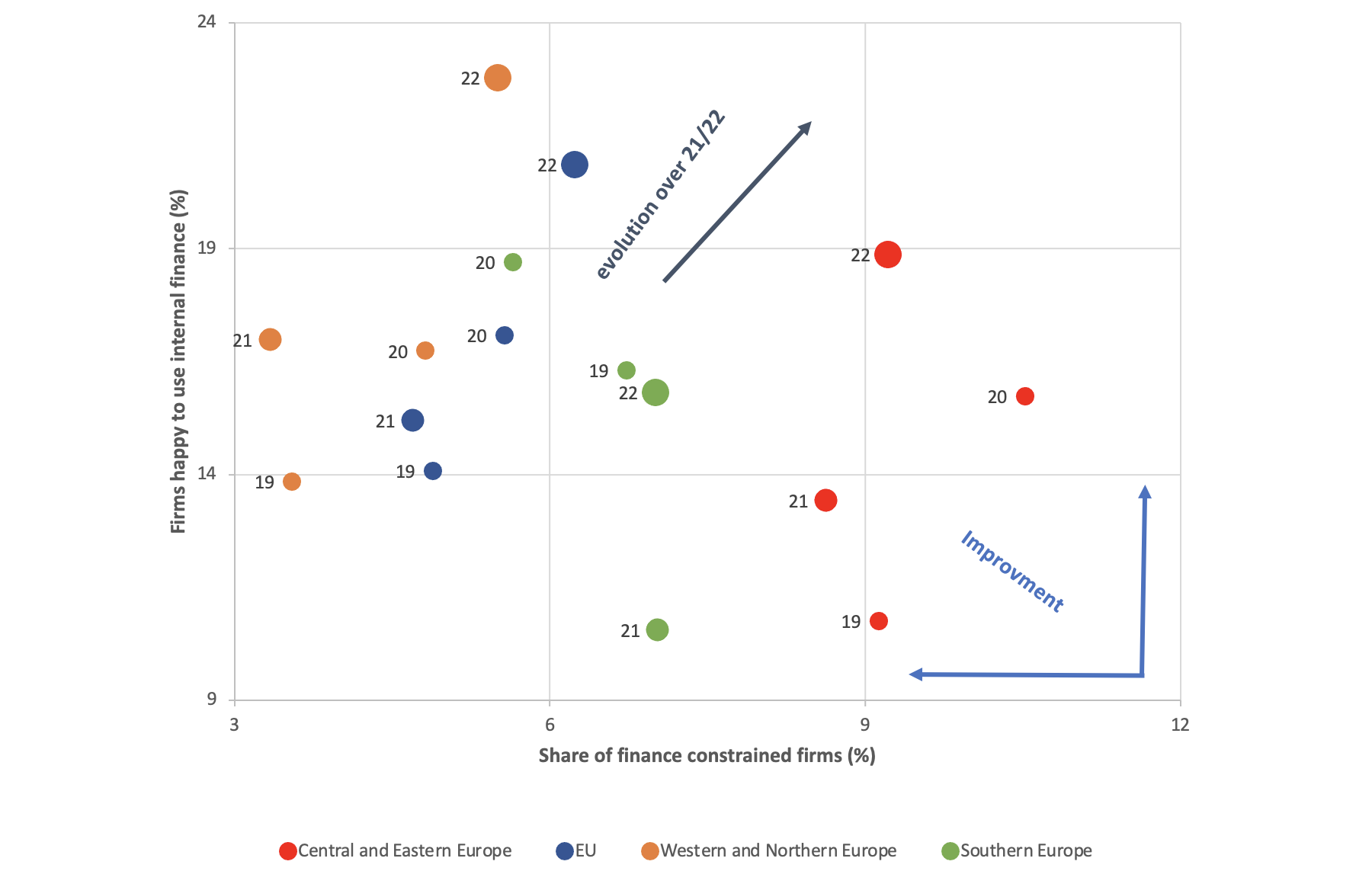

Lower profits weaken internal financing capacity, and the increased vulnerabilities are likely to tighten further firm access to external funding sources. Overall, firms are likely to reduce investment. In Figure 6, we correlate two results from the EIBIS: the financial constraints indicator and the willingness to use internal financing. Financial constraints are likely to affect investment less when firms are not as dependent on outside funds. A move towards the top or left of reflects an improvement in financing conditions. From 2021 to 2022, the willingness to rely on internal financing increased by around 4 percentage points across the board, supported by a strong recovery in profits. In parallel, a substantial increase in the share of finance-constrained firms was recorded. Hence, the change in investment financing conditions was unclear last year. However, access to external finance remains more problematic for some types of firms. Investment gaps are more frequently reported when firms are finance-constrained, and the difference tends to be stronger for firms investing heavily in intangible investment (EIB 2023).

Figure 5 Simulated increase in firm risk indicators

Source: EIB estimations based on EIBIS-ORBIS historical matched database and EUROSTAT turnover statistics.

Note: see EIB (2022) and Harasztosi et al. (2022).

Figure 6 Financial capacity of firms

Source: EIBIS (2019-22).

Question: Looking back at your investment over the last three years, was it too much, too little, or about the right amount to ensure the success of your business going forward? Too little.

Policy implications

The simulations developed in this column suggest that the current environment could have a substantial impact which is overall not systemic but is especially pronounced for firms operating in some sectors and in some countries. This challenging environment must not derail the recovery in investment. The response to the energy shock should lay the foundation for a more efficient and reliable EU energy market, tackling uncertainty and setting out a clear, ambitious pathway for the green transition. A European response is paramount. Uncoordinated responses risk undermining economic convergence and the creation of a level playing field. Progress towards a more integrated and developed financial system must, in turn, support the far-reaching twin transitions to more green and digital economies.

References

Bialek, S, C Schaffranka and M Schnitze (2023), “The energy crisis and the German manufacturing sector: Structural change but no broad deindustrialisation to be expected”, VoxEU.org, 17 January.

Delanote, J, D Revoltella and T Bending (2022), “'How will European firms respond to new shocks? Latest evidence from the EIB Investment Survey”, VoxEU.org, 18 November.

Du Bella, G, M Flanagan, K Foda, S Maslova, A Pienkowski, M Stuermer and F Toscanis (2022), “Natural gas in Europe – the potential impact of disruptions to supply”, IMF Working Paper 22/145.

EIB – European Investment Bank (2023), Investment Report 2022/2023: Resilience and renewal in Europe.

Harasztosi, P, L Maurin, R Pál, D Revoltella and W van der Wielen (2022), “Firm-level policy support during the crisis: So far, so good?”, International Economics 171: 30-48.

Maurin, L and R Pál, (2020). “Investment vs debt trade-offs in the post-COVID-19 European economy”, EIB Working Paper 2020/09.

Rezessy, A, M Tomasi and E Maincent (2015), “Are high energy prices harming Europe’s competitiveness? Assessing energy-cost competitiveness in Europe”, VoxEU.org, 22 January.

Zinglersen, C (2022). “Energy price volatility and energy sources in Europe”, presentation at the ECB Forum on Central Banking 2022, Sintra, 27-29 June.