In an environment of increased interconnectedness but also heightened vulnerability, with rampant externalities and spillovers, there seems to be an objective need for more European public goods (hereafter, EPGs). Health may be the newest entrant in the discussion, but the list is long: it extends from traditional policy domains such as defence, security, and development cooperation, to research and development (R&D) in large and risky projects, climate change mitigation, and an adequate digital infrastructure (Fuest and Pisani-Ferry 2019, Papaconstantinou 2020). Also stimulated by the design and expected impact of Next Generation EU (Mahieu et al. 2021), the issue of EPGs has recently been connected to the debate on the reforms of European fiscal rules (Buti and Messori 2021, Garicano 2022, Maduro et al. 2021).

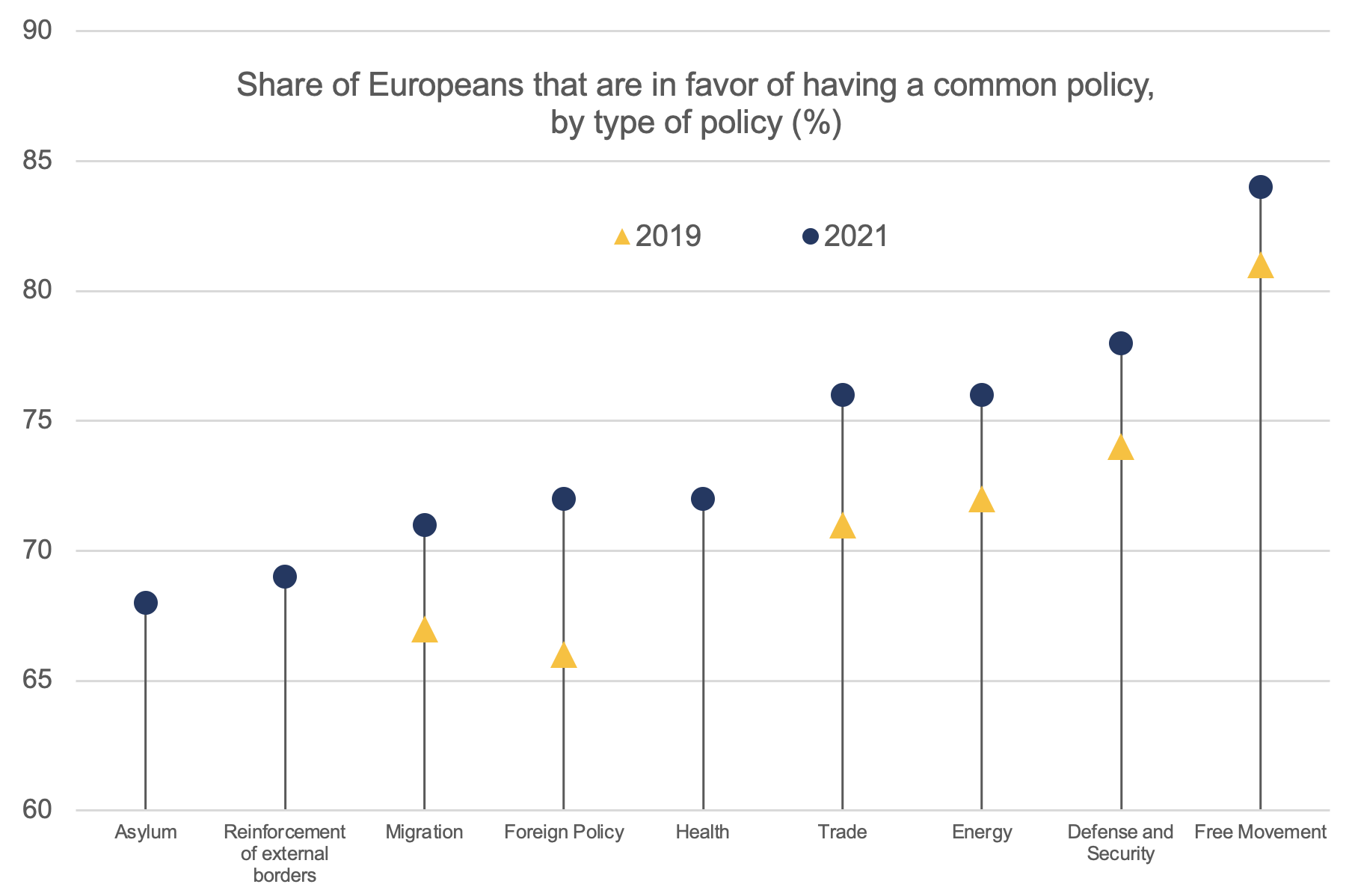

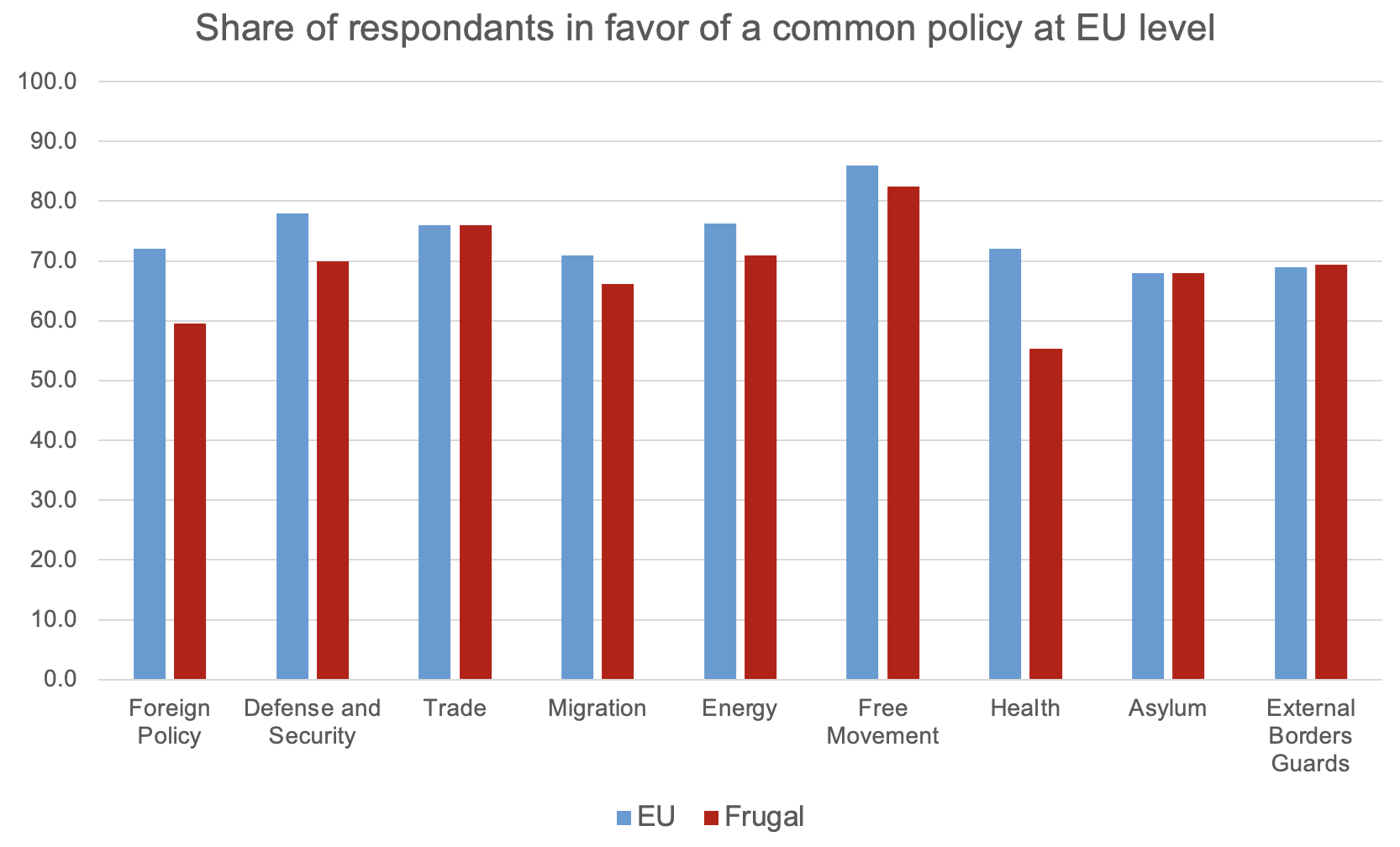

There is no direct evidence about demand for EPGs, but along with a general move in state/market boundaries, the pandemic seems to have accentuated a majority view in member states towards more confidence in and reliance on European-level solutions. Eurobarometer data suggest a strong majority of Europeans favour a common policy across diverse policy areas, from free movement to defence, energy, trade, health, foreign policy, even migration and asylum; despite national differences, the result holds even for the so-called ‘frugals’ (see Figure 1). The attitude of EU citizens seems to be more favourable to the supply of EPGs than what policymakers are able and willing to deliver.

Delivery and financing of European programmes

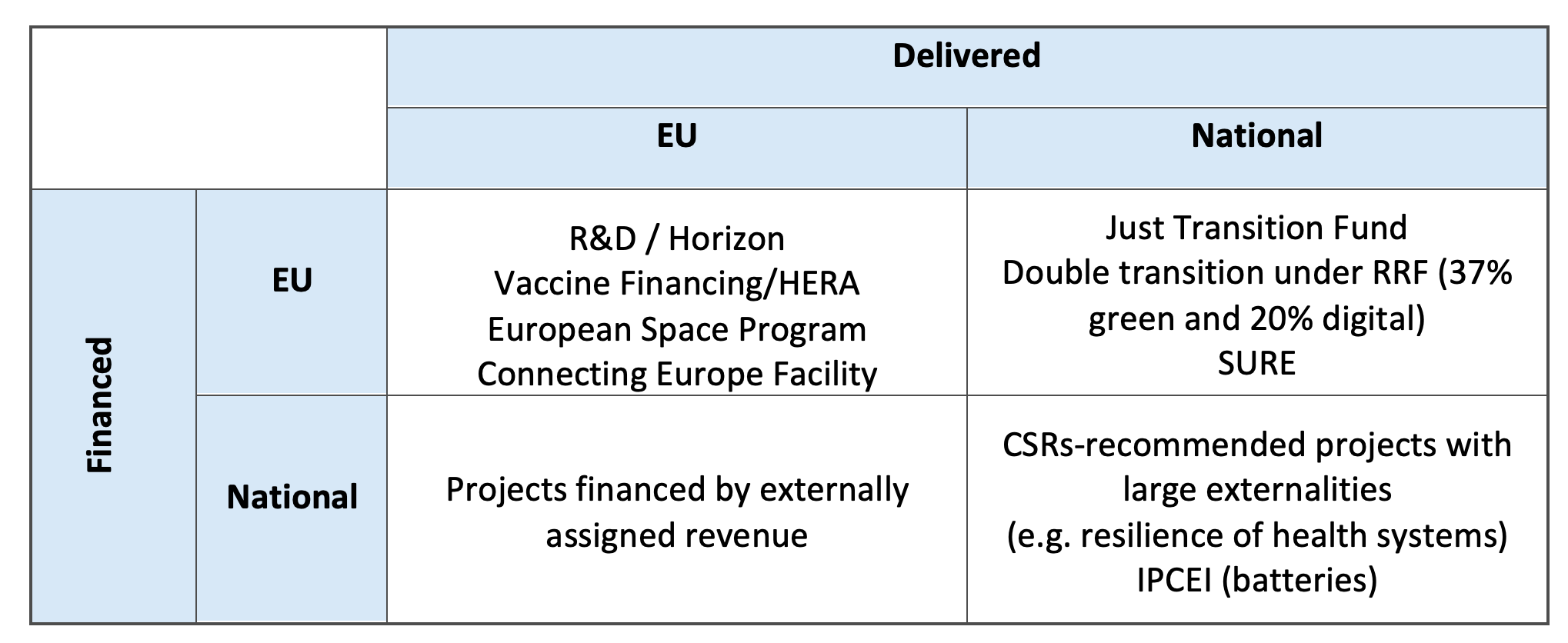

A simple conceptual framework may help frame the analysis. In Table 1, we distinguish between delivery and financing of European programmes.1 ‘Pure’ EPGs are those delivered and financed at the EU level. Recent examples are the common procurement of vaccines and the creation of the European Health Emergency Preparedness & Response Authority (HERA).2

Figure 1 Attitudes towards common policies

Note: Frugal countries include Austria, Finland, The Netherlands, Sweden, and Denmark.

Source: Eurobarometer, Spring 2019/Spring 2021

The other three combinations involve member states either in the delivery, financing, or both. Where the delivery takes place at the national level, we are in the realm of EPGs ‘by aggregation’. A notable example is the projects to foster the double transition in the Recovery and Resilience plans (RRPs).3 The screening of their projects by the Commission, including the application of the ‘do no significant harm’ (DNSH) principle, aims at ensuring that the targets of the funds allocated to the green and the digital transition are credibly attained.

The possibility to deliver EPGs at the EU level whilst maintaining financing at national level is foreseen via the so called ‘external assigned revenue’, i.e. funds conferred by member states and non-EU countries to the EU budget to be spent on community actions.4 Third-country participation in Erasmus uses this budgetary technique.

The projects where both financing and delivery takes place at national level can still qualify as EPGs ‘by aggregation’, provided they are consistent with a clearly defined common European goal. An example are the Important Projects of Common European Interest (IPCEI), which allow state aid support for breakthrough innovations that would not otherwise materialise because of the market risks such projects entail. The most notable IPCEI is a pan-European project on a new generation of batteries.

Table 1 Classifying European programmes

Source: Authors’ elaboration. Entries in the table are non-exhaustive examples.

Whilst EPGs ‘by aggregation’ play an important role given the complexity of the EU system, there are potential shortcomings compared to ‘pure’ EPGs: projects delivered at the EU level but financed via national budgets may be called into question should national priorities change; similarly, EU financed EPGs delivered at the national level may lack the cross-country coherence. Finally, EPGs financed and delivered by member states may combine both weaknesses. Therefore, the issue of how to increase the supply of ‘pure’ EPGs has to be addressed.

Thinking about incentive compatibility

In the EU, second-best solutions will always be part of the game. What’s more, also for ‘non-pure’ EPGs, one can get closer to the frontier by better incorporating the EU dimension and priorities. Nevertheless, if increasing the supply of ‘pure’ EPGs financed and delivered at EU level is important, how does one nudge the process to deliver these? This seems to be a classic incentive compatibility problem, whose solution is to tweak political incentives and institutional dynamics for a better outcome by making such projects politically viable. Critical will be the need to show that the EU level does not undermine what happens at national level.

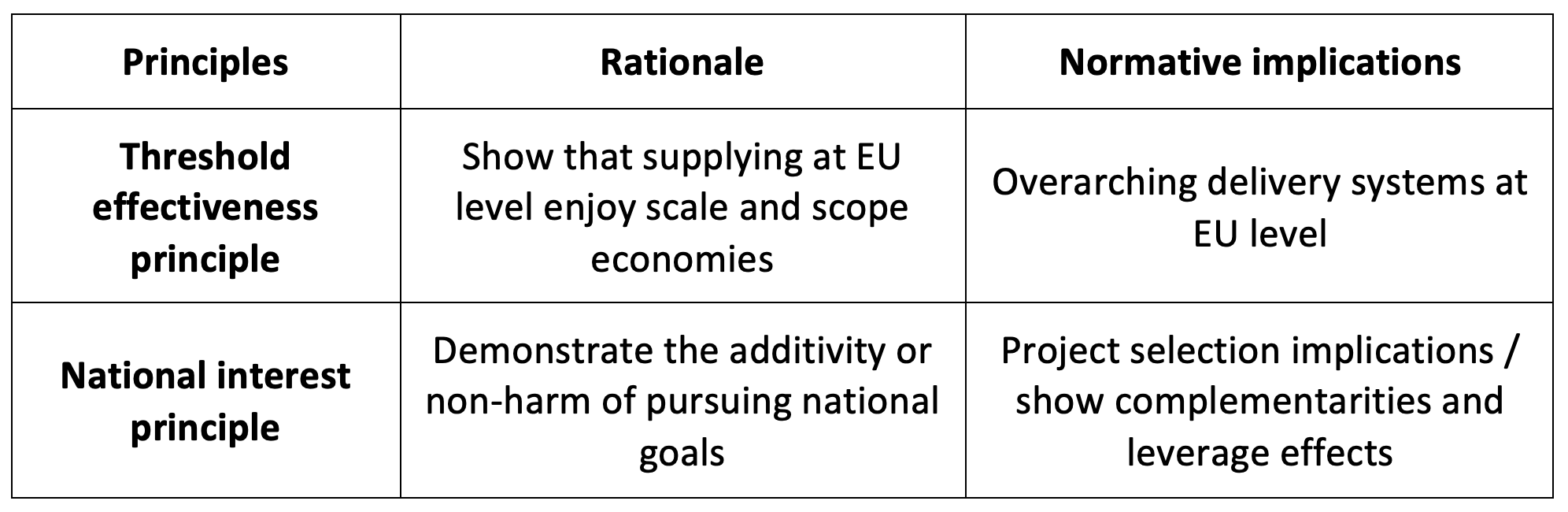

In Table 2, we identify two principles that could help us think in this direction and increase the supply of ‘pure’ EPGs. The first is a threshold effectiveness principle, which concerns goods where supplying at the EU level enjoys scale and scope economies that are clearly superior to the supply at national level. This relates to the classic part of fiscal federalism theory and subsidiarity; but it may require a threshold effect to ensure political acceptance, as with the funding of a large and important project such as vaccine development at the EU level.

Table 2 Principles for European public goods

Source: Authors’ elaboration.

The second is a national interest principle. As legitimacy of decision-making in member states rests on national interest, it is important to demonstrate additivity or non-harm when pursuing EPGs. In security, a traditional domain for public goods, the recent Australia–UK–US (AUKUS) submarine issue can lead to build critical mass at the EU level. Agglomeration effects could be an incentive for stronger countries' buy-in; for smaller countries, it would be spillover effects.

It goes beyond the scope of this column to apply the principles sketched out above to the identification of specific EPGs. Nonetheless, examples of pure EPGs consistent with the above approach could be research and procurement of vaccines, hydrogen, connectivity, defence, big data infrastructures, semiconductors, and a Climate Fund. Beyond these allocative public goods, a euro area stabilisation function financed and delivered at the EU level could be seen as representing a ‘pure’ EPG.

The political economy of mindset change

The aim of this column was to start exploring the political economy of the insufficient supply of EPGs. Clearly, further analysis and debate are required before it can be applied in an operational way. Nevertheless, the key is in the juxtaposition between an EU budget made up of national contributions versus a true EU-level resource. The former has proved extremely difficult to increase in order to invest in public goods (for an early criticism, see Sapir et al. 2003, Buti and Nava 2003).

Raising the national practice of earmarking resources for certain activities to the EU level could help funding when the principle of separation is strongly present, while also allowing for direct accountability on spending. A more promising avenue however is true EU-level resources to bring decision-making on funding out of national optimisation and thereby help finance ‘pure’ EPGs. There is a parallel to other policy areas where EU has exclusive competence, such as the single market and trade. But it requires a mindset change for EU-level policy.

The discussion on new own resources prompted by the funding of NextGenerationEU represents a step in the right direction.5 It rests on a solid economic rationale: as the need for EPGs goes up (as in health safety), so does the need for supply of public goods built on mechanisms for own resources that are linked to economic activity at the EU level. It is a development which may also command public support (Maduro and Woźniakowski 2020).6 The template for decisions currently foreseen however may be too limited for the broader ambitions on supplying EPGs. The future discussions on a possible permanent central fiscal capacity beyond Next Generation EU (e.g. Buti and Messori 2021) may provide the opportunity to raise the stakes.

Authors’ Note: The opinions expressed in this column are the authors’ only and should not be attributed to the institutions they are associated with. The authors would like to thank, without implicating, Lourdes Acedo-Montoya, Pasquale d’Apice, Andrea Mairate Paolo Pasimeni, Jean Pisani-Ferry, and André Sapir for very helpful comments on earlier versions. We are grateful to Pauline Ennouchy and Juan Antona San Millan for valuable research assistance.

References

Buti, M (2021), The Man Inside: A European Journey through Two Crises, Bocconi University Press.

Buti, M and M Messori (2021), “The search for a congruent euro area policy mix: vertical coordination matters”, VoxEU.org, 13 October.

Buti, M and M Nava (2003), "Towards a European Budgetary System", EUI Working Papers, RSC 2003/8.

D’Apice, P and P Pasimeni (2020), “Financing EU Public Goods: Vertical Coherence between EU and National Budgets”, EUI Working Papers, RSCAS, 47.

European Commission (2021), “The Next Generation of Own Resources for the EU Budget”, COM(2021) 566, December.

Fuest, C and J Pisani-Ferry (2019), "A Primer on Developing European Public Goods", EconPol Policy Report, Vol. 3, November.

Garicano, L (2022), “Combining environmental and fiscal sustainability: A new climate facility, an expenditure rule, and an independent fiscal agency”, VoxEU.org, 14 January.

Maduro, M and T Woźniakowski (2020), "Why Fiscal Justice Should be Reinstalled Through European taxes that the Citizens Will Support - A Proposal", STG Policy Analysis Papers, December.

Maduro, M, P Martin, J C Piris, J Pisani-Ferry, L Reichlin, A Steinbach and B Weder di Mauro (2021), “Reforming the EU macroeconomic policy system: Economic requirements and legal conditions”, VoxEU.org, 16 December.

Mahieu, G, P Pfeiffer, J Varga and J in 't Veld (2021), “A stylised quantitative assessment of Next Generation EU investment”, VoxEU.org, 4 August.

Papaconstantinou, G (2020), "European Public Goods: Just a Buzzword or a New Departure?" in European Court of Auditors, Realizing European added value, ECA Journal, 2020/3.

Sapir, A, P Aghion, G Bertola, M Hellwig, J Pisani-Ferry, D Rosati, J Viñals, Helen Wallace, M Buti, M Nava and P M Smith (2003), Agenda for a Growing Europe – The Sapir Report, Oxford University Press.

Endnotes

1 Broadly in line with our distinction, D’Apice and Pasimeni (2020) and Buti and Messori (2021) discuss the coherence between EU and national projects.

2 The common purchase of vaccines was financed initially via the Emergency Support Instrument (ESI), the EU budget emergency fund. Subsequently, the member states were asked to top it up, based on their relative GDP, to achieve the necessary funding.

3 Next Generation-EU offers important lessons on the issues to be addressed when pushing for more European public goods. On the one hand, the direction in national Recovery and Resilience Plans (RRPs) for the green and digital transition incorporates overarching EU goals. Therefore, although delivery takes place at national level, reforms and investments respond to European priorities. On the other hand, the final July 2020 decisions involved a reallocation against the ‘pure’ public good element that was present in the original Commission proposals.

4 From a legal standpoint, the funds borrowed in the markets to finance Next Generation-EU are considered external assigned revenue. In our analysis, we take a narrower definition of externally assigned revenue.

5 The European Commission came forward with proposals on new own resources in December 2021. They are based on Emission Trading System, carbon border adjustment, and the forthcoming implementation of Pillar 1 of the OECD agreement on reallocation of profits of large multinationals. See European Commission (2021).

6 A YouGov survey in 11 member states, conducted with the School of Transnational Governance of the European University Institute suggests that while Europeans are divided on the extent to which national budgets should provide more EU funding, they seem to support new own resources at a European level, such as those from supra-national levies on emissions (a carbon tax), internet companies, financial transactions, or business profits in general.