Financial integration is the process through which different regions or countries become more financially interconnected. This process involves the free circulation of capital and financial services among those areas. It usually determines an increase in capital flows across regions (private risk sharing) and a convergence of prices and returns for financial assets and services.

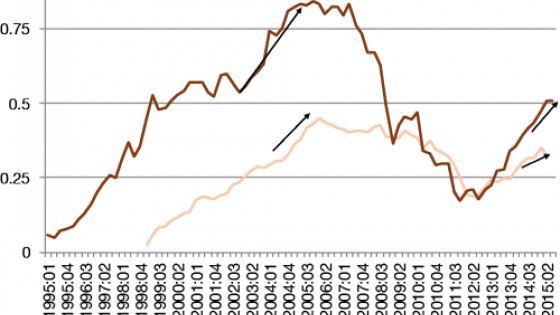

In the aftermath of the Global Crisis, the European financial system still lacks private risk sharing, i.e. cross-border banking and capital markets activities. Limited private risk sharing is the main cause of the build-up of asset bubbles across the Eurozone (pre-Crisis) and the fast retrenchment of capital flows (post-Crisis) within national boundaries (Furceri and Zdzienicka 2013, IMF 2013, Lane 2013). Price convergence with no quantity convergence (cross-border holdings) is a broken promise of financial integration. After the rapid realignment of price and quantity indicators during the Global Crisis, the integration process has now restarted, with initial signs that quantity and price indicators are diverging again in a pre-Crisis fashion.

Figure 1. Eurozone price-based and quantity-based FINTEC, 1995-2015

Source: ECB.

To avoid another ‘tragedy’, much of the policy attention has been rightly directed towards ways to improve the quality of financial integration, as it plays a key role in capital flow movements (Milesi-Ferretti and Tille 2011). The size and composition of cross-border investment flows and portfolio holdings is thus crucial for the quality of financial integration. Financial integration is also complementary to greater fiscal policy coordination, which accounts for only 20-25% of the absorption capacity in in major regions (Furceri and Zdzienicka 2013, Anderson et al. 2015). Recent evidence also points at the limited contribution during the Crisis in the US, despite several bailouts that took place (Duwicquet and Farvaque 2013).

Risk sharing, however, can take different shapes. A combination of intertemporal private risk sharing – institution-based capital flows (traditional commercial bank loans) – and cross-sectional private risk sharing – market-based capital flows (equity transactions or foreign direct investments) – can produce quality integration. Intertemporal risk sharing provides a safeguard to idiosyncratic shocks and the stability of the European system during isolated shocks, such as the dotcom bubble. Banking union is taking care of scaling up this protection at the European level and to promote more unsecured cross-border lending activities (such as retail credit markets). The overarching objective of the European Commission’s Capital Markets Union (CMU 2015) is instead to develop more cross-sectional risk sharing via capital markets, which protects from aggregate systemic risk produced by permanent asymmetric shocks. In particular, it aims at allocating more private savings in the purest form of cross-sectional risk sharing, such as equity and foreign direct investments.

Beyond financial stability, the cross-sectional risk dispersion of market mechanisms also produces additional positive spillover effects, such as:

- Better transmission of monetary policies via market-based reference rates, which improves the effectiveness of actions like quantitative easing;

- Greater access to finance and availability of equity tools, such as crowd funding and private equity, more suitable to fund innovation (Giordano and Guagliano 2014);

- Rebalancing of the financial system through risk diversification, as research confirms the parabolic relationship between the size of the financial sector and growth if institution-based funding (credit markets) overgrows (Cecchetti and Kharroubi 2012, 2015; Langfield and Pagano 2015); and

- Supporting the restructuring of the banking system via the offer of market solutions to banks’ offloading of non-performing exposures.

Europe’s financial structure

Europe’s financial structure lacks capital market activity to support the economy. Banking sector assets are more than three times Europe’s GDP, with even higher incidence on the economy than the Chinese banking system. It is not by chance that financial instability continues to bite in the two regions where the financial system is less diversified, i.e. Europe and China.

Figure 2. Simplified structure of the financial sector in the EU, 2010-2014 (% GDP, average)

Notes: For debt securities, we use outstanding amounts and exclude financial institution debt securities (which are implicitly included in the banking sector assets statistics). For equity, we use domestic market capitalisation. For US bank assets data, we include gross notional value of derivative positions and credit union assets.

Data Sources: IMF (GDP), BIS, ECB, US Fed, BoJ, PBoC, WFE, FESE, individual stock exchanges. Eurostat for exchange rates.

In a report supported by a group of academics and experts, titled "Europe's untapped capital market: rethinking integration after the great financial crisis" (Valiante 2016), I collect ample evidence that Europe’s capital markets are poorly functioning and underdeveloped. The outcome of this financial structure is a landscape with limited role for market-based finance. Governments and financial institutions bond issuance are the only exception, but their activism is mostly a result of the financial difficulties of recent years.

Figure 3. Capital market structure (value of outstanding securities, excluding derivatives, average 2010-14, % of GDP)

Notes: Derivative markets, excluded from this chart, include securitisation, derivative contracts, and indexes (exchange-traded products; see following sections). ‘Public equity markets’ are equal to domestic market capitalisation.

Data Sources: BIS, ECB, WFE, FESE, individual stock exchanges. Eurostat for exchange rates.

While acknowledging great heterogeneity across countries, EU households held on average, between 2007 and 2014, more than 30% of their financial assets in cash and deposits, compared to 13% in the US. Direct holdings of securities and investment funds totalled a mere 23% versus 45% overseas. European non-financial corporations’ liabilities are the smallest (relative to GDP) compared to major economies, due to the limited contribution of listed shares and corporate bonds. Non-financial corporations’ debt funding is 77% in bank loans, compared to less than 40% in the US.

Overall, the EU economy lacks sufficient equity funding. Equity markets, in particular, are fragmented along geographical borders. Their aggregate turnover is only a fifth of their US counterparts. Despite the recent astonishing growth, the asset management industry is still limitedly spread across the EU and with scarce retail penetration. Distribution channels of investment products are mostly closed and segmented by local banking systems and national marketing laws. There are over 32,000 investment funds in Europe compared to roughly 7,600 in the US, with an average size respectively of €186 million and €1.34 billion. Many of these investment funds are set up to charge upfront fees and other fixed charges. Crowd finance is still in its infancy, but it may play an important role, especially for small and medium enterprises, as it offers risk dispersion like open markets but with a high degree of risk customisation for capital seekers. Private equity and venture capital investments are only a fraction of their US counterparts.

How to improve the quality of financial integration?

Facing overwhelming evidence about the poor quality of Europe’s financial ecosystem, the capital markets union project has the responsibility to rebuild trust in the single market for a multi-currency area. After 60 years, the single market is still standing on the way of any future fiscal policy coordination. The experience of the US suggests that, besides war periods, the federal budget only became an important risk absorber with the Great Depression. It is the period after the Sherman act of 1890 and after Supreme Court cases (such as Standard Oil Co. of New Jersey v. United States, 221 US 1 1911) that finally opened up the US single market and promoted greater integration of the private sector.

In this spirit, the European Capital Markets Research Group research identifies 36 barriers to cross-border capital market integration and suggests 33 policy recommendations to create an organic action plan for capital markets integration. Three main actions occur in a capital market transaction: price discovery, execution, and enforcement. A barrier is most harmful if it produces unpredictability of the costs of such actions, which a financial market transaction would then not be able to discount. Inability to price risk creates uncertainty and ultimately preclude new trading activity to take place.

Price discovery is the process of ‘discovering’ the market price that is the closest approximation to the reserve value of the investor. Barriers to price discovery (cost unpredictability) emerge with all rules and market practices that reduce cross-border data comparability. For instance, among the 36 cross-border barriers, the report identifies areas of IFRS 9, such as the definition of “loan impairment” and the use of internal evaluation model, as an important barrier to data comparability, ultimately increasing the inability to evaluate the company ex ante and so raising prohibitive transaction costs for investors. Due to much optionality in accounting rules, national data about companies’ financial results are often not comparable across borders and require investors to hire local accountants and lawyers to deal with differences that ultimately may not be reconciled at all.

Execution is the set of procedures that are involved in the finalisation of a financial transaction once counterparties’ interests are matched. To avoid cost unpredictability, this requires market entry and exit requirements to be fair ad non-discriminatory. Here, national withholding tax reclaim procedures, which cost about €8.4 billion per year, are an example of unfair and discriminatory procedures vis-à-vis foreign investors.

Enforcement is the process of ensuring the smooth performance or renegotiation of a financial contract, i.e. the enforcement of private contracts, including minority shareholders, retail investors and creditors’ rights. It can take place via public (e.g. courts) and private mechanisms (e.g. arbitration). The average quality of Europe’s courts is low and the cross-border insolvency proceedings (despite recent reforms) are still very cumbersome and with uncertain procedures that increase cost unpredictability.

As a result, Europe’s capital markets are still in the hands of 28 national supervisors that often fight to defend the national interests of small and inefficient financial industries that offer access to local capital markets. The recently created European Securities and Markets Authority has only limited mediation powers and its management cannot even vote, leaving the responsibility to protect the European interest to the sum of the national interests. It is a Europe with poor enforcement powers in the period of most intense rule making for a sector that requires strong deterrence.

Twenty years after the first empirical findings on legal and financial systems (La Porta et al. 1996), a capital markets union should bring the removal of legal and economic barriers at the forefront of the capital market integration process to achieve the needed private risk sharing for the stability of Europe’s single market.

References

Allen, F and D Gale (1995), “A welfare comparison of intermediaries and financial markets in Germany and the US”, European Economic Review 39: 179-209.

Anderson, N, M Brooke, M Hume, and M Kürtösiová (2015), "A European Capital Markets Union: implications for growth and stability", Bank of England Financial Stability Paper, N. 33, February.

Cecchetti, S G and E Kharroubi (2012), “Reassessing the impact of finance on growth”, BIS Working Papers, No. 381, July.

Cecchetti, S G and E Kharroubi (2015), “Why does financial sector growth crowd out real economic growth?”, BIS Working Paper, No. 490, February.

Duwicquet, V and E Farvaque (2013), “US Interstate Risk Sharing: A Post-Crisis Examination”, Working Paper.

European Commission (2015), “Action Plan on Building a Capital Markets Union”, Communication, COM(2015) 468 final, September 30th.

Furceri, D and A Zdzienicka (2013), “The Euro Area Crisis: Need for a Supranational Fiscal Risk Sharing Mechanism?”, IMF Working Paper, No. WP/13/198, September.

Giordano, L and C Guagliano (2014), “Financial architecture and the source of growth”, CONSOB Working Papers, No. 78, July.

International Monetary Fund (2013), “Towards A Fiscal Union for the Euro Area: Technical Background Notes”, Washington DC, September.

Lane, P (2013), “Capital flows in the Euro area”, CEPR Discussion Paper, No. 9493, London, May.

Langfield, S and M Pagano (2015), “Bank bias in Europe: Effects on systemic risk and growth”, Economic Policy, 61st Panel meeting, Bank of Latvia, March.

Milesi-Ferretti, G M, and C Tille (2011), “The great retrenchment: international capital flows during the global financial crisis”, Economic Policy 26: 66, 285-342.

Valiante, D (2016), Europe's Untapped Capital Market: Rethinking integration after the great financial crisis, CEPS Paperback, London: Rowman & Littlefield International.