Every three years, detailed information on the structure of the global FX market becomes available via the Triennial Central Bank Survey of Foreign Exchange and Derivatives Markets Activity (widely known as the ‘Triennial’). The 9th Triennial conducted in April 2013 covered 53 countries. It is the most comprehensive effort to collect detailed and globally consistent information on the trading activity and market structure of one of the world’s largest and most active over-the-counter markets.

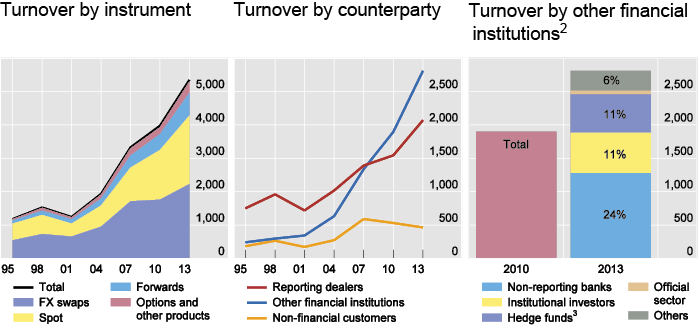

The 2013 Triennial shows that global FX turnover grew 35% from the previous survey in 2010 to $5.3 trillion per day in 2013 (Figure 1, left-hand panel).1 By way of comparison, growth between 2007 and 2010 was 20% (King and Rime 2010). In this column, we take a closer look at the drivers and trends behind the growing FX volumes based on our research in Rime and Schrimpf (2013).

Trading in currency markets is increasingly dominated by financial institutions outside of the dealer community (‘other financial institutions’ in the survey terminology), as shown by Figure 1 (centre panel). Transactions with non-dealer financial counterparties grew by almost 50%, and accounted for roughly two-thirds of the rise in the total.

New counterparty information collected in the 2013 Triennial provides a more granular picture than before of the trading patterns by non-dealer financial institutions and their contribution to turnover (Figure 1, right panel). These non-dealer financial institutions are very heterogeneous in their trading motives, patterns and investment horizons. They include smaller and regional banks, institutional investors (e.g. pension funds, mutual funds), hedge funds, high-frequency trading firms, and official sector financial institutions (e.g. central banks or sovereign wealth funds), among others.

The increased importance of non-dealer financial customers has led to the demise of the once clear-cut two-tier structure of the market, with clearly delineated inter-dealer and customer segments. Via computer-based algorithms for order placement, financial customers contribute to increased volumes not only through their investment decisions, but also by taking part in a new ‘hot potato’ trading process, where dealers no longer perform an exclusive role.2

Figure 1 Global FX market turnover

(Net-net basis,1 daily averages in April, in billions of US dollars)

Notes: 1 Adjusted for local and cross-border inter-dealer double-counting, i.e. ‘net-net’ basis. 2 Shares reported as of total FX turnover for 2013, e.g. the percentage share for institutional investors indicates that they were a counterparty in 11% of all FX deals in April 2013. 3 This counterparty segment also includes proprietary trading firms specialised in high-frequency trading.

Sources: Triennial Central Bank Survey; BIS calculations.

Who are the main non-dealer financial players in FX?

A significant fraction of dealers’ transactions with non-dealer financial customers is with lower-tier banks. While these ‘non-reporting banks’ tend to trade smaller amounts and/or only sporadically, in aggregate they make up roughly one-quarter of global FX volumes (Figure 1, right panel). As they find it hard to rival dealers in offering competitive quotes in major currencies, they concentrate on niche business and mostly exploit their competitive edge towards local clients.

The most significant non-bank FX market participants are professional asset management firms, captured under the two labels ‘institutional investors’ (e.g. mutual funds, pension funds, and insurance companies), and ‘hedge funds’. Both groups accounted for about 11% of turnover each (Figure 1, right panel). The group of hedge funds also includes proprietary trading firms specialised in high-frequency trading. The ecology of the FX market has clearly been affected by the increased participation of such players.

FX trading activity even more concentrated in financial centres

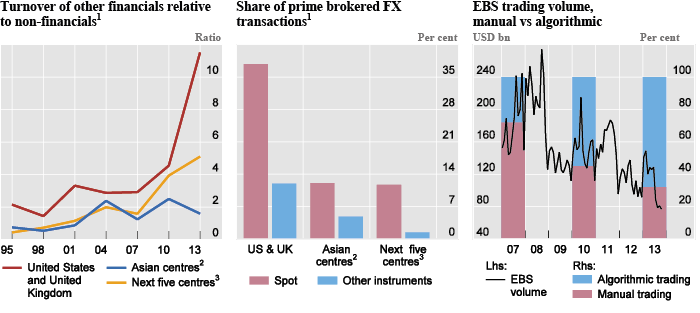

The trading of non-dealer financials such as institutional investors and hedge funds is concentrated in a few locations – in particular London and New York – where major dealers have their main FX desks. With a share of over 60% of global turnover, these two locations are the centre of gravity of the market. Dealers’ trading with non-dealer financial customers exceeds that with non-financial clients by a factor greater than 10 in these centres (Figure 2, left panel).

Prime brokerage has been a crucial catalyst of the concentration of trading, as such arrangements are typically offered via major investment banks in London or New York (Figure 2, centre panel). Through a prime brokerage relationship with a dealer, non-dealer financials gain access to institutional platforms (such as Reuters Matching, EBS or other electronic communications networks) and can trade anonymously with dealers and other counterparties in the prime broker’s name.

Figure 2 Trading of non-dealer financials and the geography of FX trading

Notes: 1 Adjusted for local and cross-border inter-dealer double-counting, i.e. ‘net-net’ basis. 2 Hong Kong SAR, Japan, and Singapore. 3 Australia, France, Germany, the Netherlands, and Switzerland.

Sources: Triennial Central Bank Survey; EBS; BIS calculations.

Shrinkage of inter-dealer trading and FX volumes by corporates

Inter-dealer trading, by contrast, is growing more slowly. A primary reason is that major FX dealing banks have effectively become deep liquidity pools themselves, given the large concentration of flows with a handful of large dealers. This allows top-tier banks to cross more trades internally and reduces the need to offload inventory imbalances and hedge risk via the traditional interdealer market. Trading volumes on traditional interbank venues like Reuters and EBS have thus either stagnated or even contracted as a consequence (see Figure 2, right panel).

A similar mechanism also partly explains that the trading volume of non-financials (mostly corporates) contracted. Firms are increasingly centralising their corporate treasury function, which allows reducing hedging costs by netting positions internally.

A new form of ‘hot potato’ trading

The distinction between the inter-dealer segment and customer-dealer segment has become much more blurred in recent years. A key driver has been the proliferation of prime brokerage, allowing smaller banks, hedge funds, and especially high-frequency trading firms to participate more actively in the process of sharing risk.

Trading activity remains fragmented, but so-called aggregator platforms allow end-users and dealers to connect to a variety of trading venues and counterparties of their choice. With more counterparties connected to each other, search costs (a key feature of over-the-counter markets) have decreased and the velocity of trading has increased. The traditional market structure based on dealer-customer relationships has given way to a trading network topology where both banks and non-banks act as liquidity providers. This is effectively a form of ‘hot potato’ trading, but where dealers are no longer necessarily at the centre.

Conclusion

Trading activity in the foreign exchange market reached an all-time high of $5.3 trillion in April 2013, 35% higher than in 2010. The results of the 2013 Triennial point to a growing role of non-dealer financial institutions (smaller banks, institutional investors, and hedge funds) in FX markets. Currency trading has become more international (especially for key emerging-market currencies like the Mexican peso or the renminbi) and trading activity is gravitating more and more to the main financial centres.

The market structure has evolved quickly in recent years, driven by technological innovations that accommodate the diverse trading needs of market participants – from retail investors to high-frequency traders. The once clear-cut two-tier structure of the market, with distinct inter-dealer and customer segments, no longer exists. The number of ways the different market participants can interconnect has increased significantly, suggesting that search costs and trading costs are now considerably reduced.

This has paved the way for (non-dealer) financial customers to become liquidity providers alongside dealers. Hence, financial customers contribute to increased volumes not only through their investment decisions, but also by taking part in a new hot potato trading process, where dealers no longer perform an exclusive role.

Disclaimer: The views expressed in this column are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the Central Bank of Norway or the Bank for International Settlements.

References

King, M R and D Rime (2010), “The $4 trillion question: What explains FX growth since the 2007 survey?”, VoxEU.org, 23 December.

Rime, D and A Schrimpf (2013), “The anatomy of the global FX market through the lens of the 2013 Triennial Survey”, BIS Quarterly Review, December.

1 When interpreting the 2013 Triennial it is necessary to bear in mind that the survey month was probably the most active period of FX trading ever recorded. The monetary policy regime shift by the Bank of Japan in early April triggered a phase of exceptionally high turnover across asset classes. Without this effect, however, FX turnover would likely still have grown by about 25%.

2 Although algorithmic trading methods have become more and more important, the subset of High-Frequency Trading (HFT) has most likely not been a very strong driver of growth in turnover. HFT strategies can both exploit tiny, short-lived price discrepancies and provide liquidity at very high frequency benefitting from the bid-ask spread. EBS estimates that around 30–35% of volume on its trading platform is HFT-driven. Speed is crucial, and as competition among HFT firms has increased, additional gains from being fast have diminished.