The seminal model of Becker (1968) describes the decision to engage in crime, based on a trade-off between costs and benefits of committing the crime. The growing empirical economics of the crime literature building on these notions highlights different potential costs and consequences for offenders once they become part of the criminal justice system. Examples include the costs of being convicted and incarcerated in terms of recidivism, labour market earnings, or spillover effects on family members (see Chalfin and McCrary 2017, Draca and Machin 2019 for recent reviews of these literatures, and Pinotti 2020 and Bhuller et al. 2019 for the cases of Italy and Norway). However, much less is known about victim-related costs, even though many crimes involve at least one victim (Bindler et al. 2020).

Although, in contrast to offending, becoming a victim of crime is not a decision, this does not imply that knowing the costs of crime for a victim is not important. Victim-related costs make up an important part of the social cost of crime and better knowledge of the (long-term) costs can speak to the non-trivial question of suitable compensation and support for victims. Previous studies have provided evidence that exposure to crime has the potential to change behaviour, risk perceptions (e.g. Salm and Vollaard forthcoming), mental health (e.g. Cornaglia et al. 2014, Dustmann and Fasani 2016), and subjective wellbeing (e.g. Cohen 2008, Johnston et al. 2018). If this is the case, then questions about labour market impacts – some of the core economic outcomes – naturally follow. From a theoretical perspective, being a victim of crime can worsen labour market outcomes either directly, through a deterioration in physical and mental health, or more indirectly as victims respond by adjusting working hours, changing jobs or even the location where they live.

In a new paper (Bindler and Ketel forthcoming), we aim to contribute to the limited evidence on the consequences of being a victim of crime by providing empirical evidence of its adverse effects on individuals’ labour market outcomes. Using unique and detailed register data from the Netherlands, we show that being a victim of crime leads to a significant loss in earnings and increase in social benefit receipt. The negative labour market responses persist over time and are accompanied by shorter-lived responses in health expenditure.

Design

One difficulty in estimating the effects of being a victim of crime is the underlying simultaneity problem. What comes first – unemployment, which potentially increases the risk of being a victim; or becoming a victim, which potentially increases the risk of unemployment? Another problem is that of selection: individuals who become a victim of crime may differ in unobservable characteristics (e.g. risk-taking behaviours) from non-victims. If these unobserved factors are also related to labour market success, this complicates identification of the causal effect. In addition to these identification challenges, researchers face a scarcity of high-quality data on both incidents of people becoming victims of crime and the respective outcomes. Previous studies have therefore mostly relied on either small-scale survey data, aggregate crime data, or (more selective) hospitalisation data to measure or proxy for incidents of becoming a victim. These types of data sources put a limit on the types of empirical approaches that can be employed to solve the simultaneity and selection problems.

The setting in the Netherlands provides new possibilities to deal with the above-mentioned issues. In the Netherlands, victims of all reported cases are registered by the police. These individual records can be linked to an almost two decade-long panel of labour market registry data (based on tax records). To account for selection into (different types of) offences, we only consider individuals who are a victim of crime during the sample period (2005-2016). That is, we exploit variation in the timing of being a victim but do not compare victims to non-victims (or even victims of one type of offence to victims of another type of offence). Intuitively, we compare labour market outcomes before and after being a victim while controlling for individual traits that do not change over time. By exploiting the monthly frequency in the data, we can trace out changes in labour market outcomes before and after the crime and assess the plausible sequence of events. Further, we can study potential spillovers by linking individuals to their respective household members. Finally, when the offender is known to the police, we observe whether the victim and the offender live in the same household, which allows us to separate out domestic violence cases (a very distinct type of crime, see also Bhalotra 2020).

Main findings

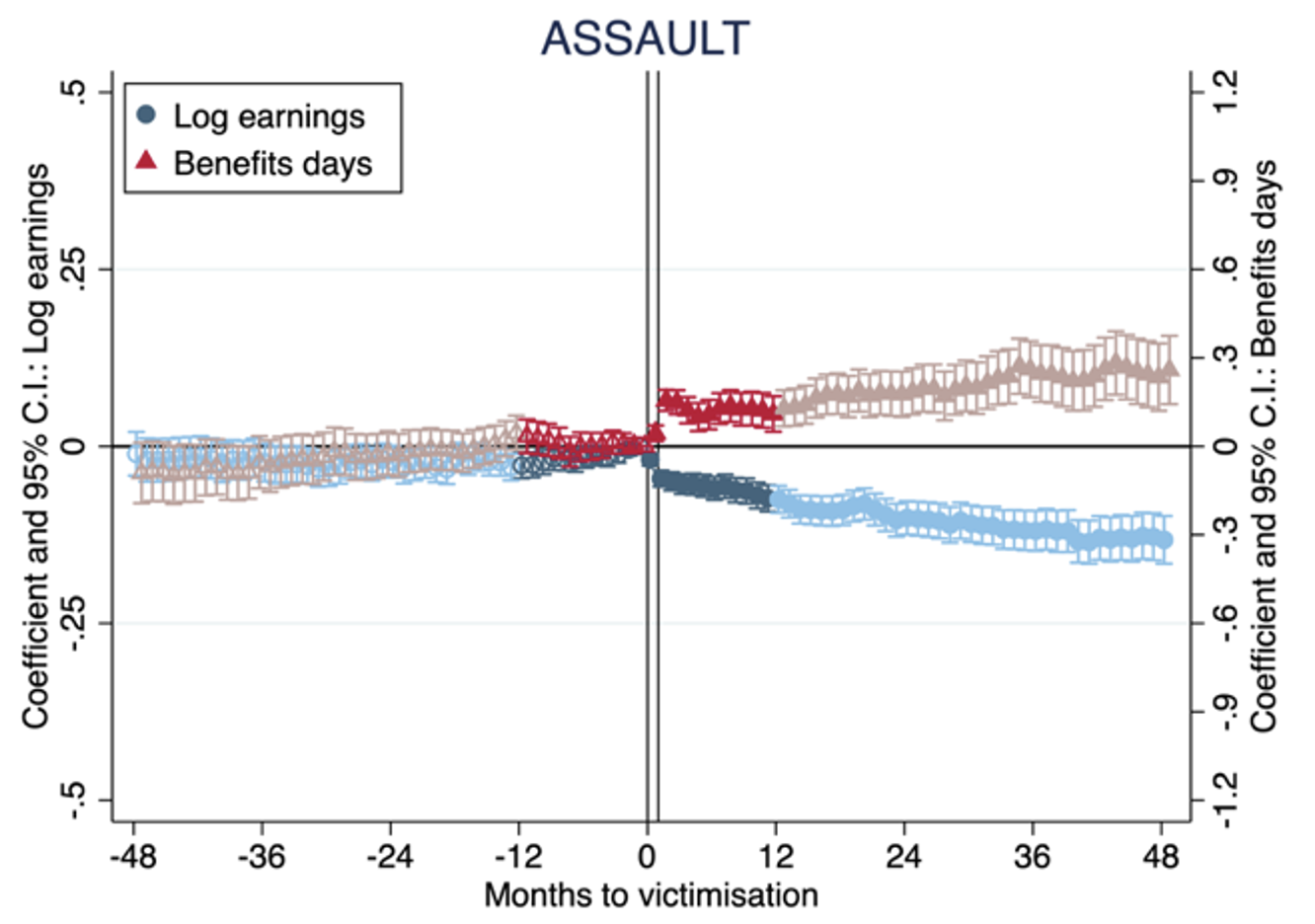

Figure 1 gives an example of the results for male victims of assault. In the top panel, the two vertical lines in the middle indicate the month of the assault. We see that male victims of assault experience an immediate and significant drop in earnings (blue circles) following the assault, implying a 7.5% drop in earnings one year after compared to the month before. At the same time, the number of days with social benefit receipt (red triangles) increase by 2.9%.

Figure 1 Male assault victims

Notes: The top panel plots the estimated effect of victimization and 95% confidence intervals for log earnings (blue dots) and days of benefits (red triangles). The solid vertical lines mark the month of the assault. The bottom panel plots the estimated coefficients and 95% confidence intervals for total health expenditure (blue dots) and mental health expenditure (red triangles) as the dependent variable. The solid vertical lines mark the year of the crime.

Source: Results based on calculations by the authors using microdata from Statistics Netherlands.

In our paper, we show corresponding figures for male and female victims and document interesting heterogeneities in the effects of being a victim of crime across offences. For offences that likely involve physical violence (assault, robbery), the effects are immediate and largest in the short term, whereas for the other offences considered in the study (threat, burglary) there are more gradual changes following the crime. These labour market effects are in many cases accompanied by short-term increases in total and mental health expenditure, as illustrated for male victims of assault in the bottom panel of Figure 1. Yet, they are also seen for victims with no or only modest increases in medical costs – especially among females. On top of the heterogeneity across offences, our study finds noticeable gender differences, with generally stronger labour market effects for females and with distinct patterns of results when it comes to domestic violence cases.

For most offences, the labour market outcomes do not return to levels prior to being a victim within four years. A likely explanation for such scarring effects is path dependency: individuals who become unemployed or leave the labour market may not return to work or remain long-term reliant on benefits. An additional explanation is that crime is a pivotal event that triggers other changes in life. We find suggestive evidence that being a victim of subsequent crimes and criminal involvement, as well as other life events (moves and family outcomes), may contribute to the longer-term effects.

Implications

Our findings of persistent labour market costs of being a victim of crime have important policy implications, as they speak to the ongoing debate concerning the social cost of crime and to the non-trivial question of suitable compensation for victims. What are the more indirect costs (including adverse labour market effects) and should they be considered? While this ultimately depends on the policy aim, agents of the criminal justice system (e.g. judges or juries) may be challenged to award an appropriate compensation amount to the victim and having guidelines for these amounts is valuable (e.g. Johnston et al. 2018).

Naturally, given the still scarce empirical evidence on the topic, more research will be needed to robustly inform the policy debate on questions regarding being a victim of crime, labour market outcomes, and necessary support systems. This is particularly relevant as the Netherlands has a relatively generous welfare system – both in terms of health insurance and social welfare. While our study cannot speak to this directly, one may only speculate whether the negative impacts in other countries with less generous support systems, more inequality, and/or different access to healthcare are larger than those we document here. To enable the necessary research, to fill the knowledge gap and to learn about important policy lessons, more high-quality data on being a victim of crime will be needed in the future.

References

Becker, G (1968), “Crime and punishment: An economic approach”, Journal of Political Economy, 76 (2): 169–217.

Bhalotra, S (2020), “A shadow pandemic of domestic violence: The potential role of job loss and unemployment benefits”, VoxEU.org, 13 November.

Bindler, A, R Hjalmarsson, and N Ketel (2020), “Costs of victimization”, Handbook of Labor, Human Resources and Population Economics, Springer.

Bindler, A and N Ketel (forthcoming), “Scaring or scarring? Labour market effects of criminal victimisation”, Journal of Labor Economics.

Bhuller, M, G Dahl, K V Løken, and M Mogstad (2019), “Incarceration can be rehabilitative”, VoxEU.org, 24 March.

Chalfin, A and J McCrary (2017), “Criminal deterrence: A review of the literature”, Journal of Economic Literature 55 (1): 5–48.

Cohen, M A (2008), “The effect of crime on life satisfaction”, The Journal of Legal Studies 37 (S2): 325–353.

Cornaglia, F, N E Feldman, and A Leigh (2014), “Crime and mental wellbeing”, Journal of Human Resources 49 (1): 110–140.

Draca, M and S Machin (2015), “Crime and economic incentives”, Annual Review of Economics 7: 389–408.

Dustmann, C and F Fasani (2016), “The effect of local area crime on mental health”, The Economic Journal 126: 978–1017.

Johnston, D W, M A Shields, and A Suziedelyte (2018), “Victimisation, well-being and compensation: Using panel data to estimate the cost of violent crime”, The Economic Journal 128 (611): 1545–1569.

Pinotti, P (2020), “Burden of proof: Measuring and understanding crime”, VoxEU.org, 1 August.

Salm, M and B Vollaard (2021), “The dynamics of crime risk perceptions”, American Law and Economics Review 23(2): 520-561.