Climate policies have often been difficult to pass and implement even when the objective of limiting global warming is broadly accepted. Therefore, understanding the determinants of public support for climate policies is crucial for policymakers who must devise and implement strategies to achieve net zero emissions targets. Over 140 countries – representing 90% of global emissions – have now adopted or announced targets of carbon neutrality by around mid-century. But while commitments and pledges to curb climate change are growing, policies to achieve these goals still lag. With currently implemented policies, average temperatures are still projected to rise to around 2.7°C by 2100 (Climate Action Tracker 2021, Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change 2022).

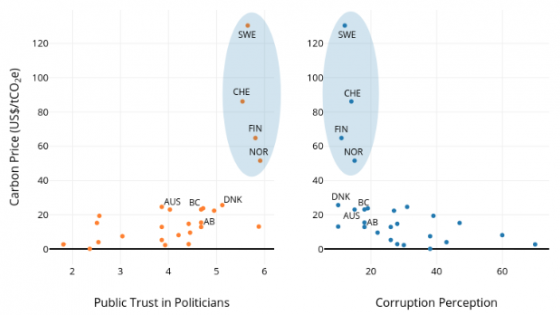

A growing empirical literature explores the drivers of support for climate policies. Whitmarsh and Capstick (2018) provide an overview of work on public attitudes toward climate change and Drews and van den Bergh (2016) summarise the research on what determines support for climate policies. However, the literature mostly focuses on attitudes towards and acceptability of carbon taxes (see Hepburn and Klenert 2018, Maestre-Andrés et al. 2019 and Carattini et al. 2018 for comprehensive reviews) and on data collected in advanced economies (Fairbrother 2022). Related work by Furceri et al. (2021) argues that policy design and timing are essential to overcome political barriers and D’Arcangelo et al. (2022) call for a comprehensive climate policy mix, including complementary measures, to enhance the cost-effectiveness and social acceptability of policies.

This column presents new empirical evidence on preferences across a comprehensive set of distinct and varied climate policies. It is based on a large-scale international survey, covering both high- and middle-income countries (Dechezleprêtre et al. 2022). We collect over 40,000 responses from 20 countries, which together account for 72% of global 2017 CO2 emissions (Joint Research Centre 2018) and include 18 out of the 21 largest emitters of greenhouse gases.

Our standardised and detailed survey questions allow us to elicit policy views as well as the underlying reasoning of respondents, enabling us to identify which individual characteristics and beliefs are associated with policy preferences. Using pedagogical video treatments, we test the causal impact of providing careful and educational explanations about climate change impacts and policies.

Across countries, climate change is seen as an important problem

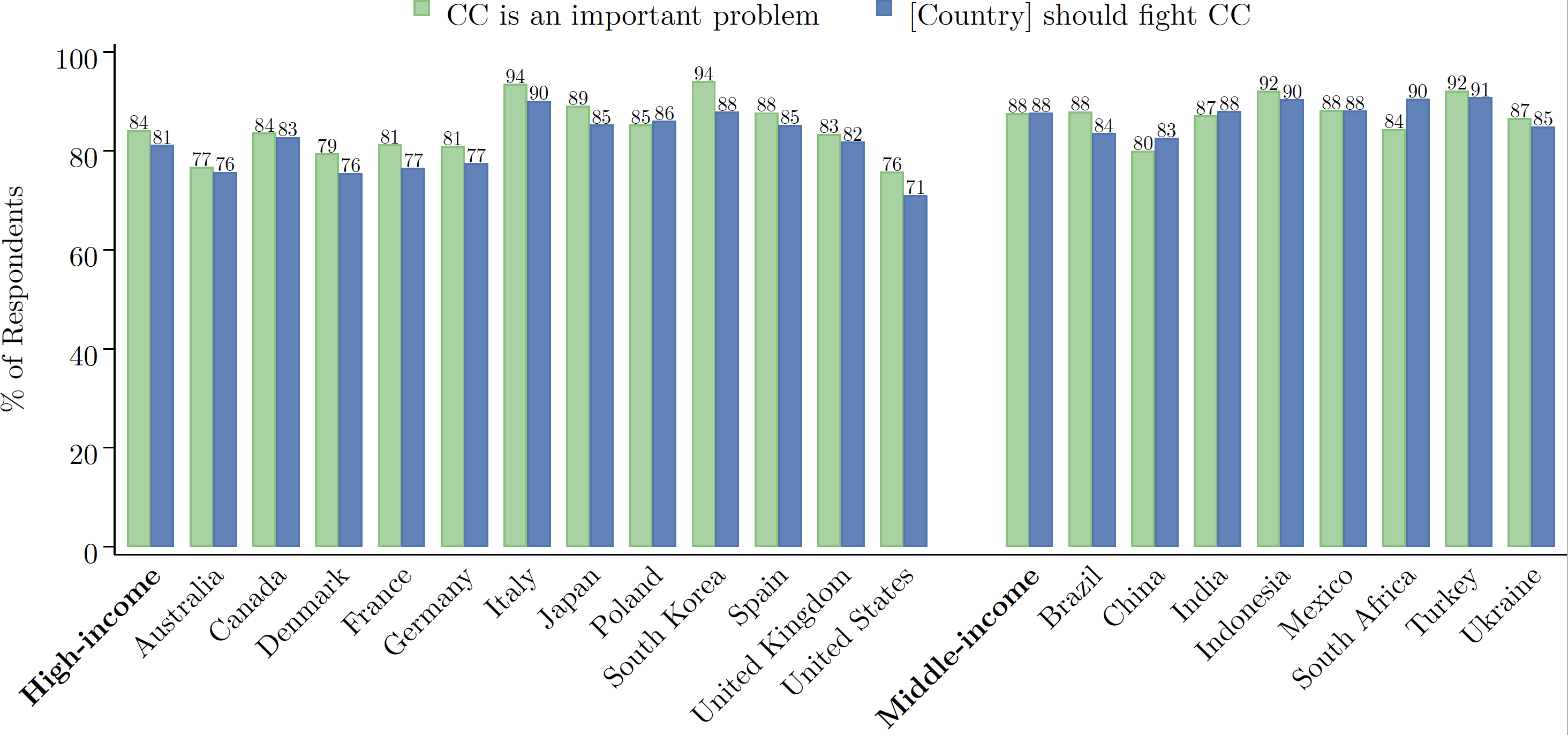

In each of the 20 countries covered, at least three-quarters of respondents agree that climate change is an important problem and that their country should take measures to fight it (Figure 1).

Figure 1 Climate change is seen as an important problem across countries

Notes: The figure shows the share of respondents who somewhat to strongly agree that ‘Climate change is an important problem’ and that their country ‘should take measures to fight climate change’. In high-income countries, the samples are nationally representative along gender, age, income, region, and area of residence (urban vs rural). In middle-income countries, the samples are online representative. Comparisons across the two groups should be done with caution.

Source: Dechezleprêtre et al. (2022).

Three key beliefs shape support for climate policies

The core contribution of our survey is to elicit detailed reasoning about a large number of distinct climate change policies. We identify three beliefs that are major predictors of whether people support a given climate policy:

- its perceived effectiveness in reducing emissions (effectiveness)

- its perceived distributional impacts on lower-income households (inequality concerns)

- its perceived impact on people’s own household (self-interest).

These results are in line with prior findings by Douenne and Fabre (2022) focusing specifically on a carbon tax in France. Overall, 70% of the variation in support for climate policies across respondents can be explained by individuals’ beliefs and socioeconomic and lifestyle characteristics, compared to 24% explained by individual characteristics only.

Thus, to understand and predict support for climate policies, people’s beliefs about climate policies are key.

Support for various climate policies

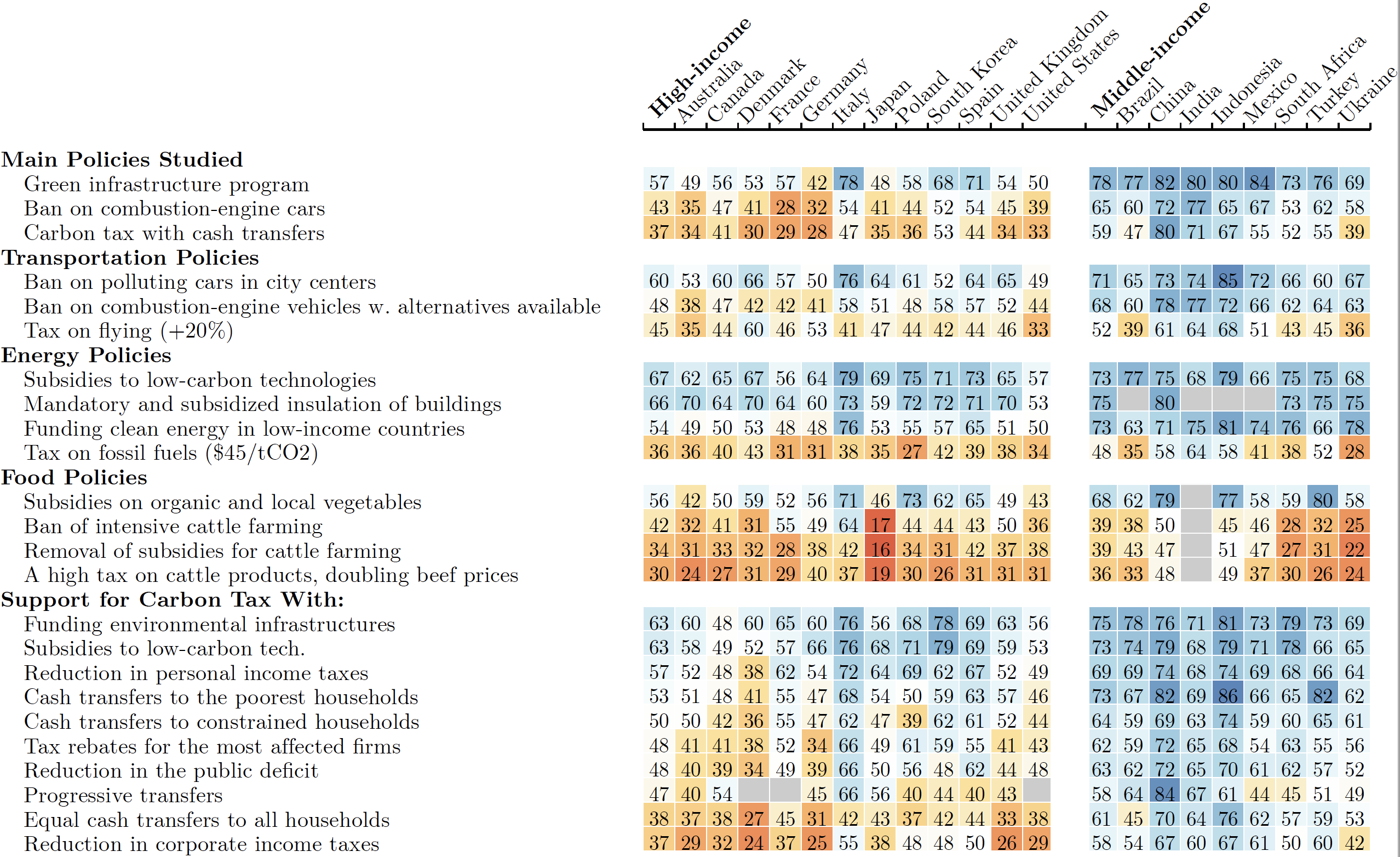

Support for climate policies strongly depends on their specific modalities. Policies that are perceived to be more effective and progressive receive more support. These include investment programmes (e.g. in green infrastructure or low-carbon technologies) that are financed by progressive taxes or public debt, carbon taxes with a strongly progressive use of revenues (such as cash transfers to the poorest or vulnerable households), and regulations rather than corrective taxes in some settings (such as bans on polluting vehicles from city centres or dense areas and the mandatory insulation of buildings) (Figure 2).

Figure 2 Support for various climate change policies

Notes: The figure shows the share of respondents who somewhat or strongly support climate change policies. Opposition or support is asked on a 5-point scale with ‘indifferent’ as the middle option. In high-income countries the samples are nationally representative along the dimensions of gender, age, income, region, and area of residence (urban vs rural). In middle-income countries, the samples are online representative. Comparisons across the two groups should be done with caution. The colours of the heat map illustrate support, from dark blue (strongest support) to dark red (lowest support). Most policies are supported by a relative majority (i.e. after excluding ‘indifferent’ answers). See Appendix Figure A4 of Dechezleprêtre et al. 2022.

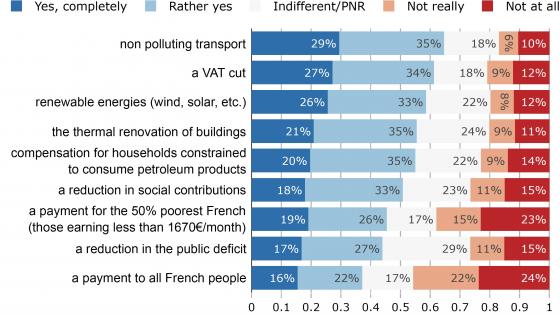

For carbon taxes, the use of revenues matters substantially for policy support, confirming previous findings (e.g. Paoli and van der Ploeg 2021). Carbon pricing can receive clear majority support when the revenues are used to fund green infrastructure and clean-technology adoption. Similarly, it receives majority support when revenues from the tax are used to lower income taxes or are used to fund cash transfers to the poorest or most fossil-fuel-dependent households. In contrast, taxes on fossil fuels without earmarking of revenues are among the least popular policies. Using revenues from carbon pricing to lower corporate income taxes is also highly unpopular across most OECD countries (Figure 2).

The role of information provision for policy support

The three core beliefs (efficiency, inequality and self-interest) have causal effects on support for climate policies. We design an experiment whereby random sub-samples of respondents in each country are shown videos on

- the impacts of climate change in their country

- how three key climate policies work (carbon tax with cash transfers, green investment programme, ban of combustion engine cars).

Respondents watch one or both videos, while a control group watches none. Respondents who watch the second video (explaining how the three main policies work and their distributional implications) are more supportive of these and other climate policies. Respondents who see the first video explaining the expected impacts of climate change in their country do not change their views as much.

Thus, information and explanations work, but more so if they address the three main concerns people have about climate policies: (1) effectiveness, (2) inequality concerns, and (3) self-interest. Information on the dangers of climate change alone without a corresponding explanation of how climate policies work in practice has only limited impact on policy support.

Individual socioeconomic characteristics and climate policy support

We also explore the extent to which personal socioeconomic characteristics, lifestyle, and energy usage are correlated with policy views. Lower availability of public transport, more reliance on cars, and, to a lesser extent, higher gas expenses are strongly correlated with opposition to climate policies. Car-dependent respondents are less supportive of bans on polluting cars. Homeowners and landlords are less supportive of mandatory insulation policies, but not less supportive of other climate-change actions.

On individual characteristics, we observe that respondents who live with children, respondents with higher education, and respondents who see themselves as ‘left-leaning’ on economic policy matters are more supportive of climate policies. The effect of income and age is heterogeneous across countries.

Respondents’ characteristics are also significantly correlated with beliefs about the effectiveness and distributional impacts of climate policies, not only with the perceived beliefs on one’s own household (self-interest). Yet, socioeconomic and lifestyle characteristics play only a minor role in predicting policy views compared to the three key beliefs we identify.

Willingness to change own behaviour is limited

In addition to policy changes, reducing emissions to net zero by mid-century may also require behavioural changes to lower individual carbon footprints. The willingness to adopt climate-friendly behaviours is conceptually distinct from support for climate policies but obviously depends on the policies in place. Given current incentives and policies, our analysis shows relatively limited willingness to make far-reaching behavioural changes in most OECD countries.

However, certain factors can encourage people to adopt sustainable behaviours. In all countries, a majority of respondents report that to consider changing their own lifestyles, an important factor is whether the well-off also change their behaviour. In addition, having sufficient financial support to adopt a sustainable lifestyle is important for a majority in most countries – particularly so for people in the lower part of the income distribution.

Policy implications

The results from these international surveys and experiments suggest three policy implications.

- Climate policies need to be (distributionally) progressive and citizens need to be made aware of their distributional (progressive) impacts. Information on how the government plans to spend revenues from carbon taxes critically influences citizens’ support for the plans.

- Explanations and information can be very effective in improving support for climate policies if they address three key concerns: effectiveness, inequality, and self-interest. Information on the dangers of climate change alone without a corresponding explanation of how climate policies work in practice has only limited impact on policy support.

- Possible financial losses from the implementation of climate policies are one of the key concerns people have. People’s experiences shape their broader perceptions and beliefs about climate change and policies, highlighting the importance of making environmentally friendly alternatives (e.g. public transportation, heat pumps, and electric vehicle charging stations) more widely available and affordable before increasing carbon taxes.

References

Carattini, S, M Carvalho and S Fankhauser (2018), “Overcoming public resistance to carbon taxes”, Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: Climate Change 9(5).

Climate Action Tracker (2021), Warming projections global update.

D’Arcangelo, F, A Johansson, I Levin and M Pisu (2022), “A framework to decarbonise the economy”, VoxEU.org, 14 February.

Dechezleprêtre, A, A Fabre, T Kruse, B Planterose, A Sanchez Chico and S Stantcheva (2022), “Fighting climate change: International attitudes toward climate policies”, OECD Economics Department Working Paper, 1714.

Douenne, T, and A Fabre (2022), “Public support for carbon taxation: Lessons from France”, VoxEU.org, 1 May.

Drews, S, and J C van den Bergh (2016), “What explains public support for climate policies? A review of empirical and experimental studies”, Climate Policy 16(7): 855–76.

Fairbrother, M (2022), “Public opinion about climate policies: A review and call for more studies of what people want”, PLOS Climate 1(5).

Furceri, D, M Ganslmeier and J Ostry (2021), “Design of climate change policies needs to internalise political realities”, VoxEU.org, 7 September.

Grömping, U (2007), “Estimators of relative importance in linear regression based on variance decomposition”, American Statistician, 139–47.

Hepburn, C, and D Klenert (2018), “Making carbon pricing work for citizens”, VoxEU.org, 31 July.

Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (2022), Climate change 2022: Impacts, adaptation, and vulnerability, Contribution of Working Group II to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change.

Joint Research Centre (2018), Fossil CO2 emissions of all world countries: 2018 report, European Commission.

Klenert, D, L Mattauch, E Combet, O Edenhofer, C Hepburn, R Rafaty and N Stern (2018), “Making carbon pricing work for citizens”, Nature Climate Change 8(8): 669–77.

Lindeman, R, P F Merenda and R Z Gold (1980), Introduction to bivariate and multivariate analysis, Scott Foresman and Co.

Maestre-Andrées, S, S Drews and J van den Bergh (2019), “Perceived fairness and public acceptability of carbon pricing: A review of the literature”, Climate Policy 19(9): 1186–204.

Paoli, M, and R van der Ploeg (2021), “Recycling revenue to improve political feasibility of carbon pricing in the UK”, VoxEU.org, 4 October.

Whitmarsh, L, and S Capstick (2018), “2 - Perceptions of climate change”, in S Clayton and C Manning (eds.), Psychology and climate change.