Sharing risk is basic to market economies. Many institutions, such as insurance companies and equity and derivatives markets, are designed to spread risk. Indications are that markets are pretty good at spreading risk within countries. However, markets seem to be less good – certainly not perfect – at spreading risk across countries (for a review of empirical work, see Kose, Prasad, and Terrones 2007). The spread of the recent financial crisis from the US to other countries is an example of international risk sharing (Mendoza and Quadrini 2009). But it was not an example of perfect risk sharing; many countries shared in the downturn, but consumption in some countries was hit harder than in others. Indeed, perfect risk sharing has been rejected repeatedly in consumption-based tests of perfect risk sharing.

But can we determine how much countries share risk in a world of less-than-perfect risk sharing?

Measuring international risk sharing

In recent work, (Flood, Marion, and Matsumoto 2009), we develop a new measure international risk sharing. The measure is the variance of a country’s share in per capita world consumption. If risk sharing were perfect, this variance would be zero. Because the measure is based on an explicit choice framework in which people do not like consumption variance, the measure is easy to interpret both at the theoretical ideal of perfect risk sharing and in the more realistic case where risk sharing is not perfect.

We measure consumption risk directly, but we do not confine ourselves to just short-term risks as has been standard in the literature. We also look beyond the business-cycle frequency to consider low-frequency risks arising from differences in per capita consumption growth rates across countries.

Our measure indicates that the globalisation era has seen little improvement in risk sharing at the business-cycle frequency, but risk-sharing gains have been widespread and large at lower frequencies.

Individual risk and international risk sharing

The risk facing an individual may be usefully broken into two parts:

- The idiosyncratic part, and

- The aggregate part.

Idiosyncratic risks may be reduced by pooling across countries. Pooling does nothing to eliminate aggregate risk.

In our paper, we adopt a model in which people dislike consumption variance. In that setting, the ideal is for people to trade assets internationally in order to pool country-idiosyncratic risks. As a result, everyone should end up consuming a fixed share of world consumption. One implication is that if one’s consumption grows faster than the world average, risk sharing is poor.

For standard preferences, a good measure of the diversifiable risk born by a country’s average individual is the variance of that country’s per capita consumption share in world per capita consumption. If risks are shared perfectly, this variance is zero. The less risk sharing there is, the larger the variance.

The evidence

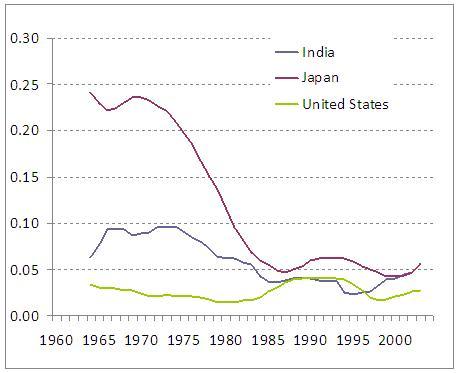

We compute this variance for windows of 15 and 20 years on a rolling basis and use it as our measure of risk sharing. Figure 1, below, samples our results. In the figure, our measure is computed for the US, Japan, and India using a 15-year rolling window. The end dates of the windows go from the early 1960s through 2004. The figure illustrates that world consumption share variance is small for the US and has fallen dramatically for Japan. For India, the measure rose and then fell in the first half of the period; it continued falling but then rose again in the second half.

Figure 1. Risk-sharing measure for the US, Japan, and India

Decomposing our measure into high-frequency and low-frequency parts yields further information.

We find that high-frequency risk is a small portion of total risk, and its sharing has changed little over the period. Low-frequency risk makes up the bulk of risk, and its sharing has improved greatly for Japan and largely been accomplished for the US. For the US, its reasonably good international risk sharing reflects the fact that its per capita consumption growth tracks closely the growth in the rest of the world. In Japan’s case, its improved international risk sharing is the result of having successfully completed its economic miracle.

Following World War II, Japan’s per capita consumption growth exceeded that of many countries; its rapid growth allowed it to become a rich industrial nation, but it also meant higher variance in its share of world per capita consumption in the process – a measure of poor international risk sharing. Once Japan’s per capita consumption growth started to look like that in the rest of the world, its measured risk sharing improved.

In India’s case, prior to its reform in the early 1990s, its per capita consumption growth was not outstanding. Its improved international risk sharing in the late 1970s and early 1980s shows that its per capita consumption growth began moving closer to world growth rates. After its reform, India experienced rapid growth. Though faster growth helps it catch up to the rest of the world, the higher variance in its share of world per capita consumption means it is not sharing risk internationally as well as before.

Conclusion

By our measure, consumption risk sharing has improved considerably for some countries, but not for others. The risk sharing that we identify is not only the widely advertised one – the one that has individuals holding insurance, equities, and derivative securities across countries, thereby spreading business-cycle-frequency risk.

We capture a deeper and much more important component of international risk sharing associated with the convergence in rates of consumption growth among countries.

This sort of risk sharing is accomplished, we guess, by the worldwide spread of technology and trade.

References

Flood, Robert, Nancy Marion and Akito Matsumoto (2009), “International Risk Sharing During the Globalisation Era,” IMF Working Paper 09/209.

Kose, M. Ayhan, Eswar Prasad, and Marco Terrones (2007). “How Does Financial Globalization Affect Risk-Sharing? Patterns and Channels,” IMF Working Paper 07/238.

Mendoza, Enrique G., and Vincenzo Quadrini (2009), “Did financial globalisation make the US crisis worse?” VoxEU.org, 14 November.