In June 2021 the US had one of the highest COVID-19 vaccination rates in the world, with over half of its population vaccinated. Since then, vaccinations in the US have stalled. With nearly a third of its population unvaccinated as of November 2021, its vaccination rate has since been leapfrogged by 46 other countries including China, Brazil, and several other developing countries (Holder 2021). This fact is all the more shocking given the many advantages that the US has, including the fact that as of April 2021 essentially every adult who wanted to get a COVID-19 vaccine could do so free of charge. If vaccination is essential to the economic and public health recovery of the US, the current situation raises several questions. Why are vaccine uptake levels so low? What can we do to encourage vaccination take up?

Previous research shows that behavioural science insights can increase vaccinations at close-to-zero marginal cost (Schubert 2016). A US study found that reminder messages – specifically those emphasising vaccine ‘ownership’ – increased vaccinations. However, the study was conducted in February 2021, before vaccines were available to the general public and when the demand for vaccines outpaced supply (Dai et al. 2021). A study in Sweden found that financial incentives of just $25 offered immediately after individuals were made eligible for the vaccine increased vaccination rates by over 4% (Campos-Mercade et al. 2021a, 2021b). Moreover, Swedish Public Health Agency data consistently show that about 90% of Swedes will “certainly” or “probably” accept the offer of a SARS-CoV-2 vaccine.1 Thus, the applicability of these findings to vaccine-hesitant populations in the US and elsewhere may be limited.

We conducted a pre-registered randomised control trial (NCT04867174 and AEARCTR- 00007405) between 24 May 2021 and 16 July 2021 to test the impact of financial incentives ($10 or $50) and different public health messages, as well as an easy vaccine scheduling link on stated intentions to get vaccinated and actual SARS-CoV-2 vaccinations of members of Contra Costa Health Plan (CCHP), the public Medicaid managed care plan in Contra Costa County, California. Medicaid is public health insurance for individuals from low-income households in the US. Contra Costa is a racially and ethnically diverse suburban county in the Bay Area California with over 1.1 million residents.

We invited unvaccinated residents of Contra Costa County who were aged 18 and over and who had self-identified as white, Black, or Latino to take part in a survey. They watched one of three videos or no video; the focus of each video was getting back to normal, safety of vaccines, and negative health consequences of remaining unvaccinated, respectively. They were also randomly assigned to receive either $10 or $50 in financial incentives, and/or a link to the county’s new public vaccination appointment scheduling system or a message about getting vaccinated with no link.

We estimated a model to quantify the relationship between whether a respondent received a vaccination within one month after completing the survey and the aforementioned nudges and incentives.

Four main results on incentives and vaccine hesitancy

Result 1: None of the behavioural nudge treatments increased vaccine uptake

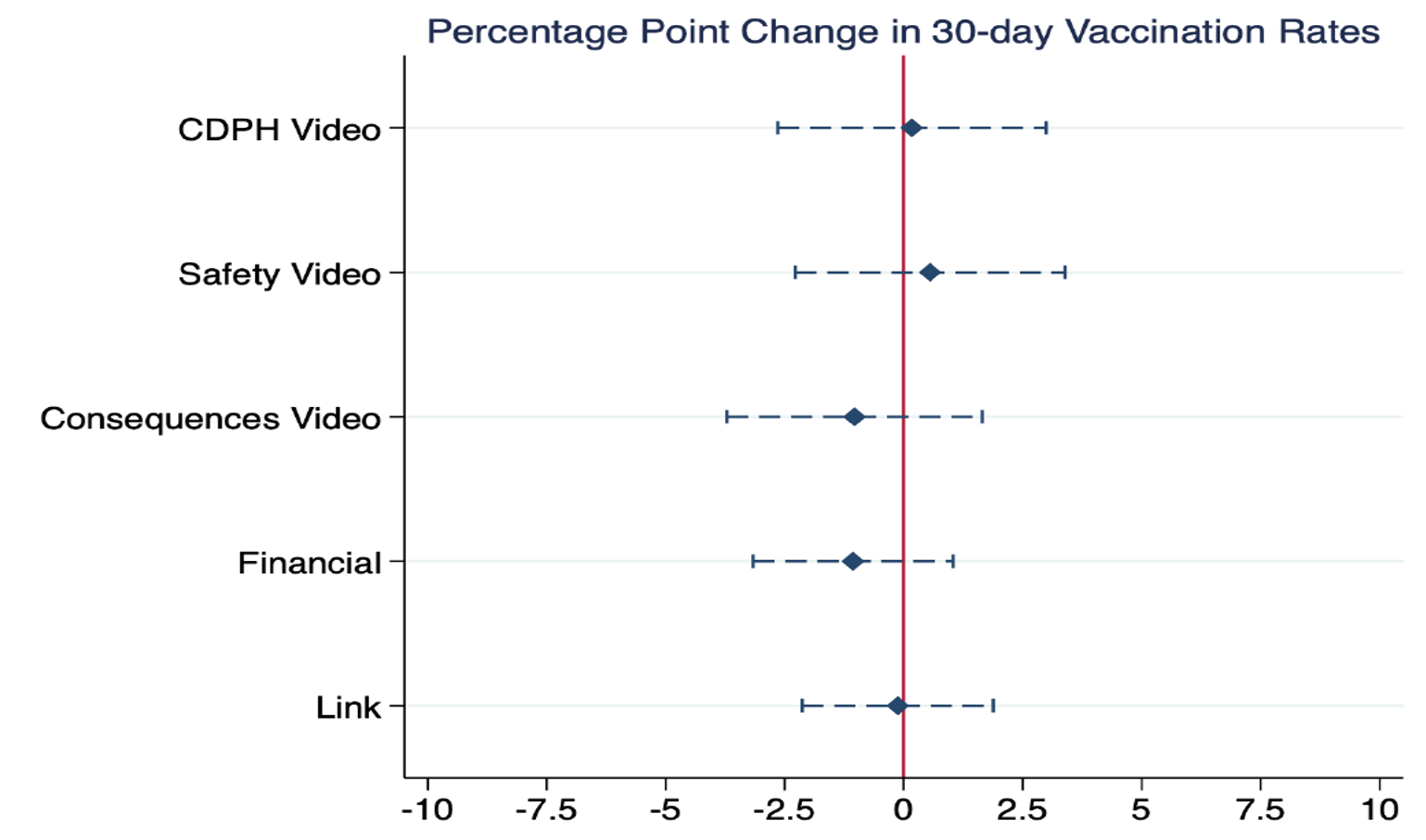

Figure 1, which plots the main effects of the interventions, shows that none of the treatments increased vaccination uptake relative to the control group. The estimates are close to zero and even relatively small effect sizes fall outside the 95% confidence intervals for most of the interventions.

Figure 1 Impact of main treatments on 30-day vaccination rates

Notes: This figure shows estimated change in SARS-CoV-2 vaccinations induced by each of our main behavioural interventions compared to the control group. Dashed lines are the 95% confidence intervals.

Result 2: Financial incentives backfired by reducing vaccination rates in older respondents and Trump supporters

For individuals ages 40 and over, 30-day vaccination rates declined by 4.5 and 4.7 percentage points in response to the $10 and $50 incentives, respectively. For individuals who showed they supported Donald Trump in the 2020 presidential election, the $50 incentive decreased vaccination rates by 4.2 percentage points. Thus, financial incentives and messaging have the potential to backfire. Experts worry that these incentives may have the contradictory effect of validating vaccine concerns among the COVID vaccine hesitant, or that they could set a dangerous precedent for future vaccination efforts if people have to be lured into clinics with offers of benefits (Hsieh 2021).

Result 3: Video messages improve vaccination intentions but do not affect actual take-up rates

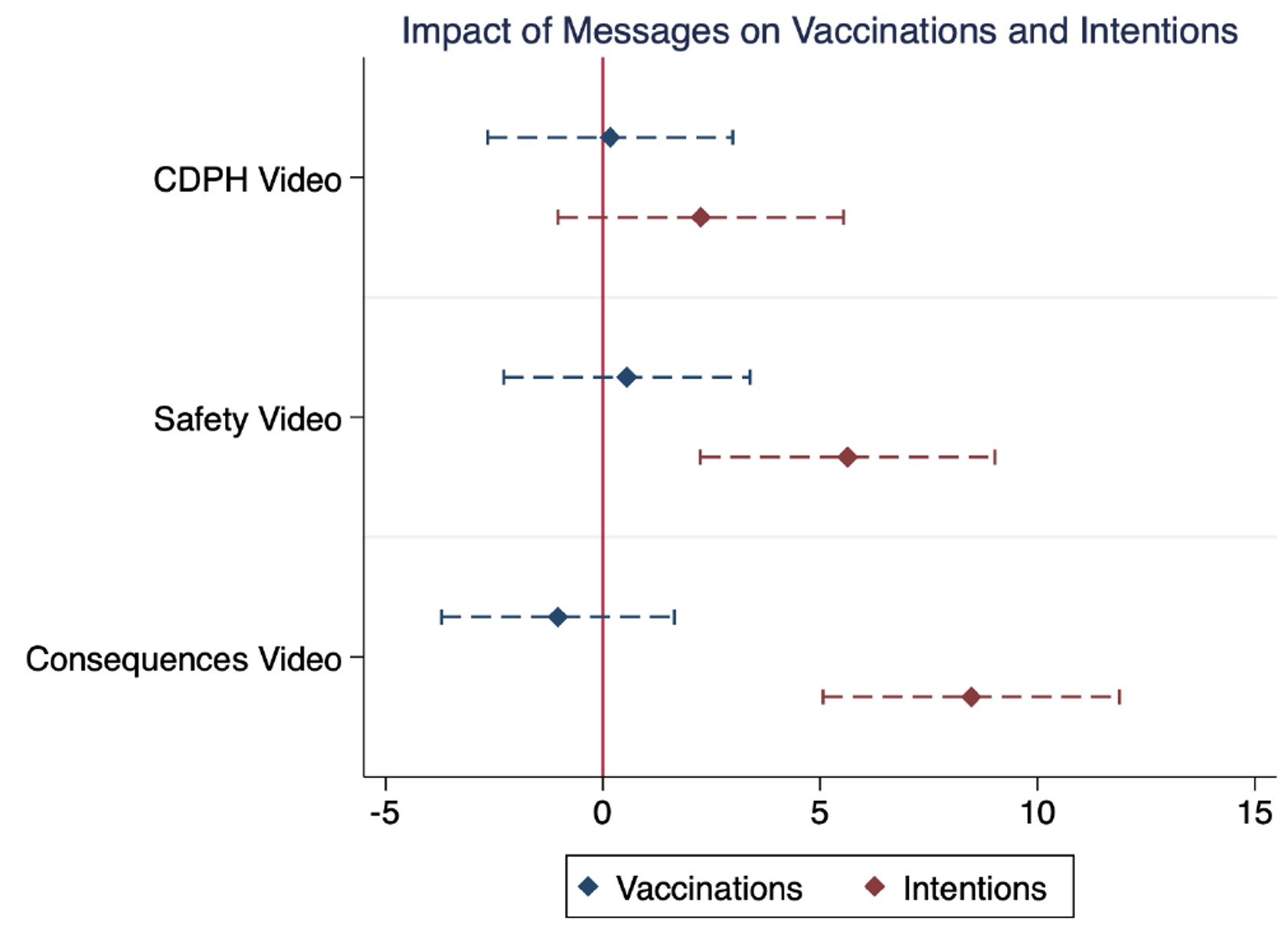

While vaccination intentions increase by 5.5 percentage points in response to the safety videos and 8.6 percentage points in response to the health consequences videos, this behaviour does not translate into actual vaccination uptake. Figure 2 summarises these findings. We compare the estimated change in SARS-CoV-2 vaccinations (in blue) and vaccination intentions (in red) caused by each of the three different public health video messages compared to control. These results imply a weak link between survey-elicited COVID vaccination intentions and actual vaccinations. Much of the COVID literature has focused on vaccination intentions (Wong et al. 2021) and not actual vaccinations. While vaccination intention studies are an expedient way to understand the impact of different policy options and are illuminating in other contexts, such as influenza vaccinations (Alsan et al. 2019), these studies may have limited value for the COVID vaccine hesitant.

Figure 2 Vaccine take-up versus vaccine intentions for SARS-CoV-2

Result 4: Race and gender concordance of public health messenger play different roles

Research has documented the benefits of patient-physician racial concordance on communication and health outcomes, underscoring the importance of a diverse workforce to care for a diverse population (Alsan et al. 2019). With COVID-19, race-concordance has had mixed effects on information-seeking about COVID-19 among Black patients in some studies, and no effect on COVID-19 knowledge or self-protective behaviours. A study in Michigan revealed significantly greater COVID-19 vaccine trial participation and uptake rejection among Black participants, which was partially mediated by medical mistrust (Thompson et al. 2021). However, in our study we find no impact of race concordance on vaccine uptake or vaccination intentions.

Interestingly, assignment to a gender-discordant physician decreased 30-day vaccination rates for the health-consequences message by 2.9 percentage points. We found this difference to be driven by individuals under the age 40, by men of all ages, and by Latinx members. For men, the negatively framed message delivered by a female physician decreased vaccination rates by 5.8 percentage points (p=0.033). For Latinx, a gender discordant negatively framed video decreased 30-day vaccination rates by 5.4 percentage points (p=0.045).

Discussion

Our findings provide several lessons for more effective, evidence-based policymaking on SARS-CoV-2 vaccinations. First, while vaccination intentions are an expedient way to study the impact of different policy options and can be illuminating in other contexts, such studies may have limited value for SARS-CoV-2 vaccinations. Our work demonstrates a weak link between self-stated vaccination intentions and subsequent vaccinations.

Second, many of the efforts that have proved popular in the past and in other contexts, including small financial incentives, are unlikely to convince a substantial share of the vaccine-hesitant to get vaccinated and may, in fact, backfire. We should have realistic expectations of what nudges can achieve during this pandemic. Our study suggests that nudges are unlikely to yield the high vaccination rates needed to produce seroprevalence levels considered population protective through reduced transmission and morbidity. Given that SARS-CoV-2 Covid-19 vaccines exert large positive spillover effects beyond their protective effects for individuals, we need to think hard about policies to increase take-up (Costa-i-Font 2021). Reaching a goal of very high vaccination rates will likely require much stronger policy levers, such as employer rules or government mandates.

References

Holder, J (2021), “Tracking Coronavirus Vaccinations Around the World”, The New York Times, 19 November.

Chang, J, M Shah, R Pramanik and S Shah (2021), “Financial Incentives and Other Nudges Do Not Increase COVID-19 Vaccinations among the Vaccine Hesitant”, NBER Working Paper 29403.

Hsieh, P (2021), “Perks and Incentives For Covid-19 Vaccination May Backfire”, Forbes, 28 May.

Thompson, H, M Manning and J Mitchell (2021), “Factors Associated With Racial/Ethnic Group–Based Medical Mistrust and Perspectives on COVID-19 Vaccine Trial Participation and Vaccine Uptake in the US”, JAMA Network Open, 27 May.

Dai, H, S Saccardo and M A Han (2021), “Behavioural nudges increase COVID-19 vaccinations”, Nature 597, 404–409.

Campos-Mercade, P, A N Meier, F Schneider, S Meier, D Pope and E Wengström (2021a), “Monetary incentives increase COVID-19 vaccinations, nudges do not”, VoxEU.org, 19 November.

Campos-Mercade, P, A N Meier, F Schneider, S Meier, D Pope and E Wengström (2021b), “Monetary incentives increase COVID-19 vaccinations”, Science, 7 October.

Schubert, C (2016), “A note on the ethics of nudges” VoxEU.org, 22 January.

Wong, L P, H Alias, M Danaee et al. (2021), “COVID-19 vaccination intention and vaccine characteristics influencing vaccination acceptance: a global survey of 17 countries”, Infectious Diseases of Poverty 10, 7 October.

Alsan, M, O Garrick, G Graziani (2019) “Does diversity matter for health? Experimental evidence from Oakland”, American Economic Review 109(12): 4071–4111.

Costa-i-Font, J (2021), “Social value and incentives for vaccine uptake” VoxEU.org, 29 June.

Endnotes

1 https://www.folkhalsomyndigheten.se/nyheter-och-press/nyhetsarkiv/2021/maj/fortsatt-stor-vilja- att-vaccinera-sig-mot-covid-19