If market expectations are rational, they are consistent with monetary policy outcomes resulting from a policy rule or the state of the economy (Hoover and Jorda 2001). This implies that market surprises would not structurally deviate from actual monetary policy decisions (the rational-expectations hypothesis implies that such ‘mistakes’ are short-lived). This means that in theory, changes in market prices around monetary events have a ‘zero mean’, no trend, and low volatility. It should be noted that this assertion assumes the policymaker has a time-invariant reaction function, which is a strong assumption.

The use of new and unconventional monetary policy instruments might imply a changing reaction function or the transposition of new instruments to the existing reaction function, which may not be well understood by market participants. This adds uncertainty about monetary policy announcements and leads to larger forecasting errors. Moreover, the implementation of asset purchase programmes has substantially expanded the central bank balance sheet. Thereby the ECB has increased its presence in financial markets. Against this backdrop we explore whether market expectations have become more sensitive to monetary policy decisions.

Research approach

We examine the impact of the communication of ECB monetary policy decisions on financial market prices. This research uses the euro area Monetary Policy Event-Study Database (MPD), constructed by Altavilla et al. (2019). The database collects monetary policy surprises, measured as intraday asset price changes right after Governing Council decisions. As a result, the data reflects the pure impact of ECB policy (surprise) announcements (whereby the direction of causality goes from monetary policy to asset prices). We focus on asset price changes around the ‘Monetary Event Window’, which includes both the ‘Press Release Window’ and the ‘Press Conference Window’.

We distinguish three subsamples: (i) a period before the global crisis (January 1999 to May 2007), when the policy rate was the main instrument; (ii) the credit crisis and the euro area sovereign debt crisis (June 2007 to December 2014), in which the ECB deployed unconventional instruments; and (iii) the period in which quantitative easing was implemented (January 2015 to June 2020). In the latter two periods the ECB also provided forward guidance on the policy rate as well as asset purchases.

To gauge the sensitivity of monetary policy surprises we examine the volatility and higher moments of the distribution of financial market surprises. The analysis is conducted for six asset classes: risk-free overnight indexed swap rates (principal components of short (one week up to one year), medium (two up to nine years) and long-term (ten and 20 years) rates), the sovereign bond spread of Italy and Spain relative to the overnight indexed swap rate, the STOXX50 index and the euro-dollar exchange rate (defined as US dollars per one euro).

Volatility of market surprises

The strength of the impact of ECB announcements is measured by the volatility of financial market surprises. High volatility reflects high sensitivity of market prices to monetary policy changes. One explanation for this can be that the ECB’s communication strongly influences financial markets. High volatility can also mean that market participants are uncertain about monetary decisions ex ante and more surprised about them ex post, resulting in larger forecast errors and extreme tail responses. This could indicate that the ECB’s reaction function is not often clear to investors.

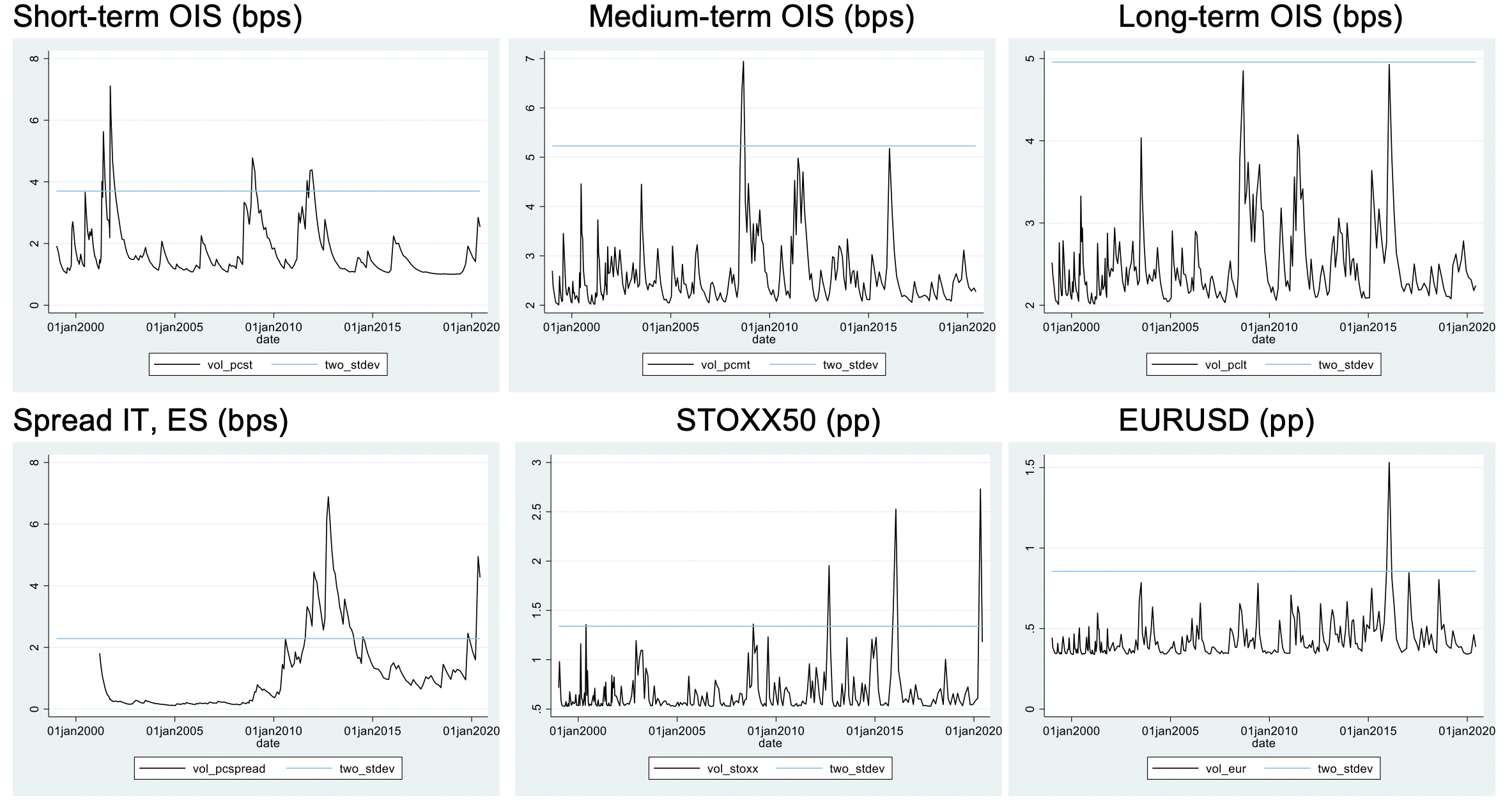

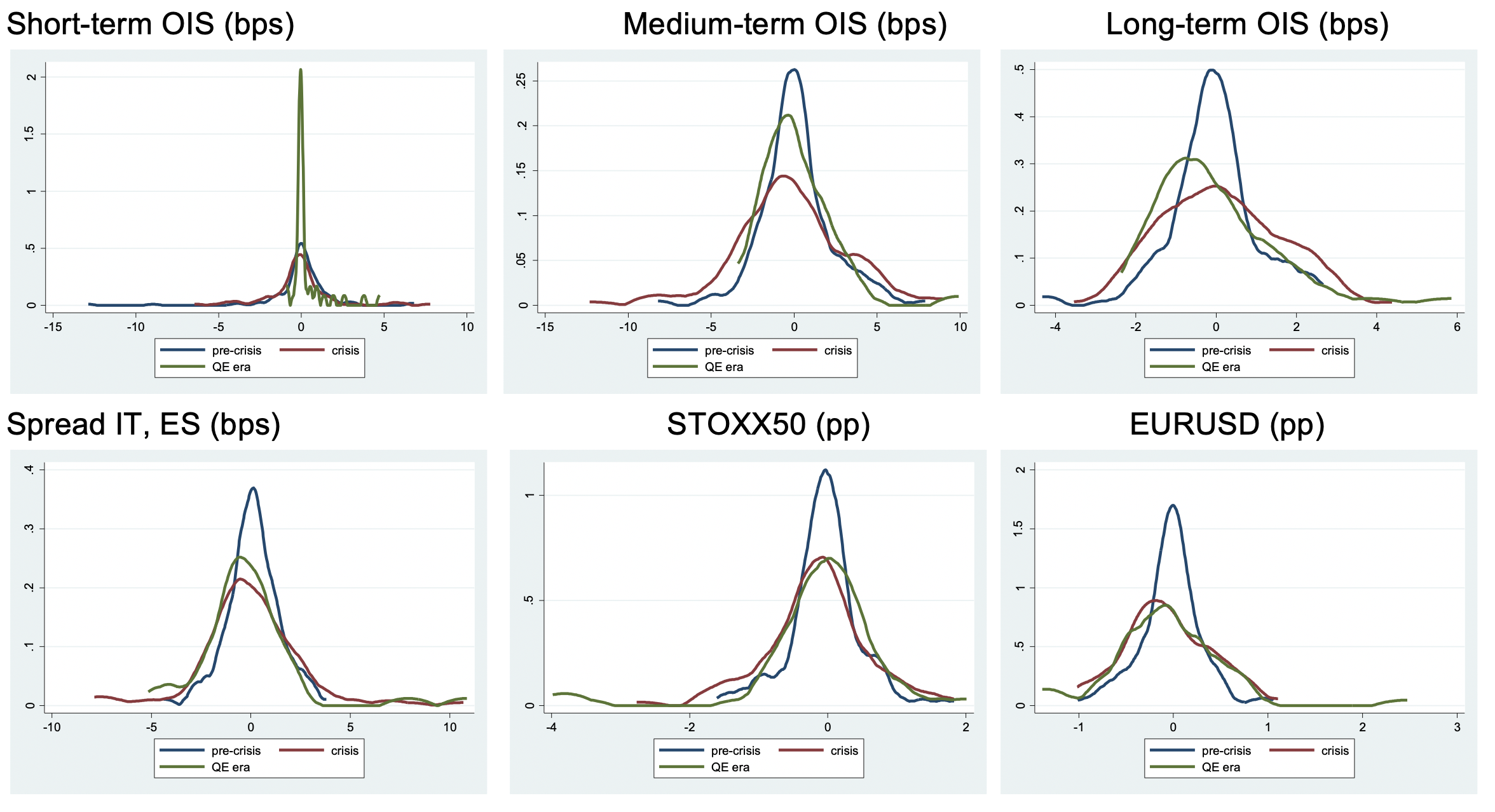

During the quantitative easing era, the volatility of the short-term overnight indexed swap rate surprises declined considerably (Figure 1). Another indication that outliers of short-term rate surprises became less frequent during this period is the high concentration around the mean of the distribution (Figure 2). These findings can be explained by the ‘effective lower bound’, at which policy rates move less. In contrast, the volatility of the long-term overnight indexed swap rate surprises was high at the start of quantitative easing in 2015, but declined afterwards (Figure 1). The latter suggests that markets were initially uncertain about the ECB’s reaction function based on quantitative easing (which influences the long-term overnight indexed swap rate through to term premium) but became more familiar with it in the following years.

The volatility of sovereign spread surprises increased noticeably between 2012 and 2015, and again this year. In a similar vein, the distribution of surprises flattened markedly, suggesting that ECB announcements led to more extreme spread surprises since the global crisis. Particularly since 2010, monetary policy measures occasionally aimed at stabilising sovereign bond markets by means of sovereign bond purchases (amongst other measures). As a result, the central bank became more present in the market (also as an investor). The increase of volatility and tail surprises since the global crisis indicates an increased sensitivity of sovereign bond spreads to monetary policy announcements, as confirmed by mean difference tests.

Figure 1 Conditional volatility of financial market surprises

Note: conditional volatility is inferred from univariate GARCH (1,1) models.

The entire distribution of conditional volatility of STOXX50 and euro-dollar surprises had shifted somewhat upwards since 2010 and peaked in 2020 (Figure 1). This is illustrated by higher mean, median, and top 25th percentiles, as well as in the more extreme values at the upper tail of the volatility distribution. In other words, monetary policy decisions became an increasingly important ‘market-moving’ event, affecting different asset classes. Most mean difference tests confirm this finding. Moreover, the distribution of stock price and euro-dollar surprises became flatter since the global crisis (Figure 2). The increased sensitivity of asset prices to monetary policy events happened in an environment of generally very low implied volatility levels. This suggests that, over time, financial markets became relatively more responsive to monetary policy events compared to other events.

Figure 2 Distribution of market surprises

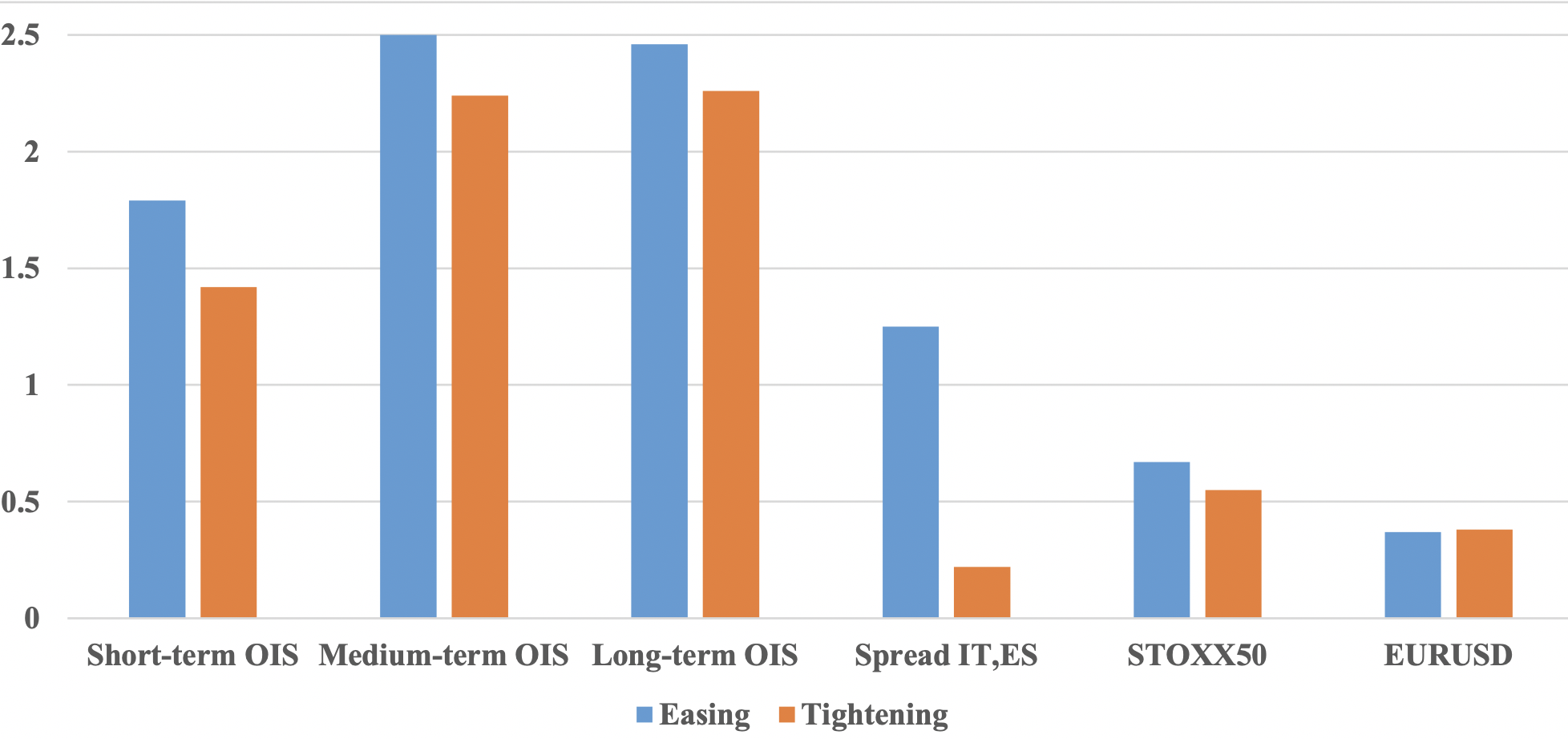

It is striking that the volatility of surprises in most asset classes was significantly higher after loosening than after tightening monetary policy decisions (Figure 3). This might reflect that market participants were more uncertain about the ECB’s reaction function in ‘bad’ states of the world with an unfavourable economic outlook, to which the ECB responded by easing the monetary policy stance.

Figure 3 Volatility of financial market surprises by policy stance (medians)

Note: The graph shows the medians of the conditional volatility for two policy stance episodes: easing (N=49) and tightening (N=20). The two-sample Wilcoxon rank-sum tests suggest that the medians are significantly different between easing and tightening episodes, for all asset classes except the exchange rate.

Conclusions

Our analysis indicates that since the global crisis asset prices had become more sensitive to monetary policy events in the euro area. While monetary easing measures likely contributed to mitigating downside risks in the financial markets and the economy, monetary policy itself seems to have become a greater source of market volatility. This emphasises the importance of clear and careful communication by the central bank, so that market participants have a good understanding of the central banks’ reaction function.

References

Altavilla, C, L Brugnolini, R S Gürkaynak, R Motto and G Ragusa (2019), “Measuring euro area monetary policy”, Journal of Monetary Economics 108(C): 162-179.

Hoover, K D and O Jordá (2001), “Measuring systematic monetary policy”, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis Review 83(4): 113-144.