Financial crises are an endemic feature of market economies. The negative effects of these crises on national economies have generally been severe, leading to banking collapses, recessions, and marked increases in government debt levels (Reinhart 2009).

Invariably this leads governments to intervene in one way or another, either to ease the damage that the crises may impose upon middle-class voters (Chwieroth and Walter 2019) or to respond to the anti-finance sentiment emerging in the society by increasing the regulations to a socially-desired level (Dagher 2018). Alternatively, politicians may take advantage of the prevailing interventionary sentiment in the aftermath of financial crises and introduce new policies that will favour the preferences of the financial industry at the expense of society.

In a recent paper (Saka et al. 2020), we trace the roots of these policy interventions back to policymakers’ incentives by exploiting the variation in political accountability across a large set of countries over four decades. We first motivate our analysis with a simple theoretical setup and then provide empirical evidence to argue that policymakers take into account both public and private interests as they undertake policy interventions after financial crises.

Based on a newly merged panel of 94 countries over the period 1973 to 2015, we employ a quasi-difference-in-differences methodology and compare the level of financial liberalisation between the two periods immediately before and after a financial crisis. This helps us capture the causal impact of a financial crisis on actual government policies across seven different financial domains and show that financial crises in general trigger a process of re-regulation in financial markets.

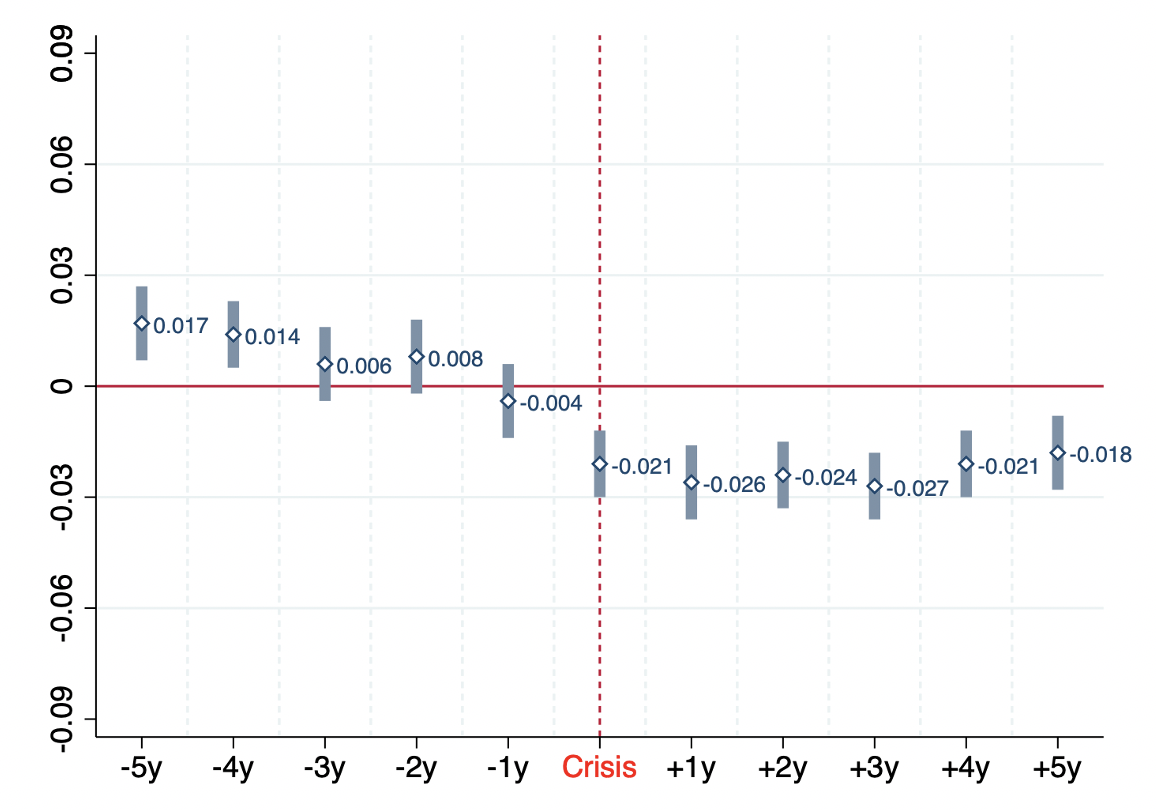

Figure 1 plots the estimates for the effect of a crisis on the degree of financial liberalisation (vertical axis). It can be seen that immediately after the crisis, financial liberalisation declines, i.e. governments tend to re-regulate financial markets.

Figure 1 Timeline for the effect of a crisis year on average financial liberalisation

Notes: The figure plots the estimates for βτ from the rolling specification in Equation 3 in Saka et al. (2020). Reform database is obtained by merging two subsets of observations from Abiad et al. (2010) and Denk and Gomes (2017). Data on financial crises is obtained from Laeven and Valencia (2018). Robust standard errors are clustered at the country level and confidence intervals are at 90% significance level.

Next, we compare the differences in post-crisis policymaking between democratic and autocratic settings, conjecturing that democracies are more likely to reflect public preferences due to higher political accountability for policymakers. Indeed, we find that re-regulation after financial crises are only common in democratic settings (as opposed to autocracies), which – also in line with our theoretical prediction – points to a public-interest channel mainly due to increased accountability of the politicians in democratic settings.

This finding echoes the earlier argument that policymakers in democracies have to respond to middle-class concerns on financial stability to avoid punishment in upcoming elections (Chwieroth and Walter 2019). It shows that post-crisis policymaking – at least to some extent – is driven by the public interest.

In order to trace the private-interest channel, we use a technical aspect of elections in democratic countries as a plausibly exogenous setting that increases the possibility that policymakers become less responsive to public concerns and behave more in line with their private incentives. We assume that the incumbent policymakers feel politically less accountable and thus put more weight on their private interests when they face a term limit. We compare democratic leaders’ policy reactions to financial crises when they can be freely re-elected in the next term and when they cannot due to a binding term limit (i.e. being a lame-duck politician).

By treating the periods with term limits on the incumbent politician as a plausibly exogenous setting that lowers political accountability, we find that a significant portion of the re-regulations in the aftermath of financial crises is driven by private interests. Specifically, we detect that policy interventions occur both when politicians face a binding term limit and when they do not; however, the effect is almost four times larger in the former case.

This result is robust to within-party estimations as well as when controlling for various types of political heterogeneity across countries and specifically around crisis episodes. Further employing a test recently proposed by Oster (2019) ensures that our findings are unlikely to be driven by other unobservable factors.

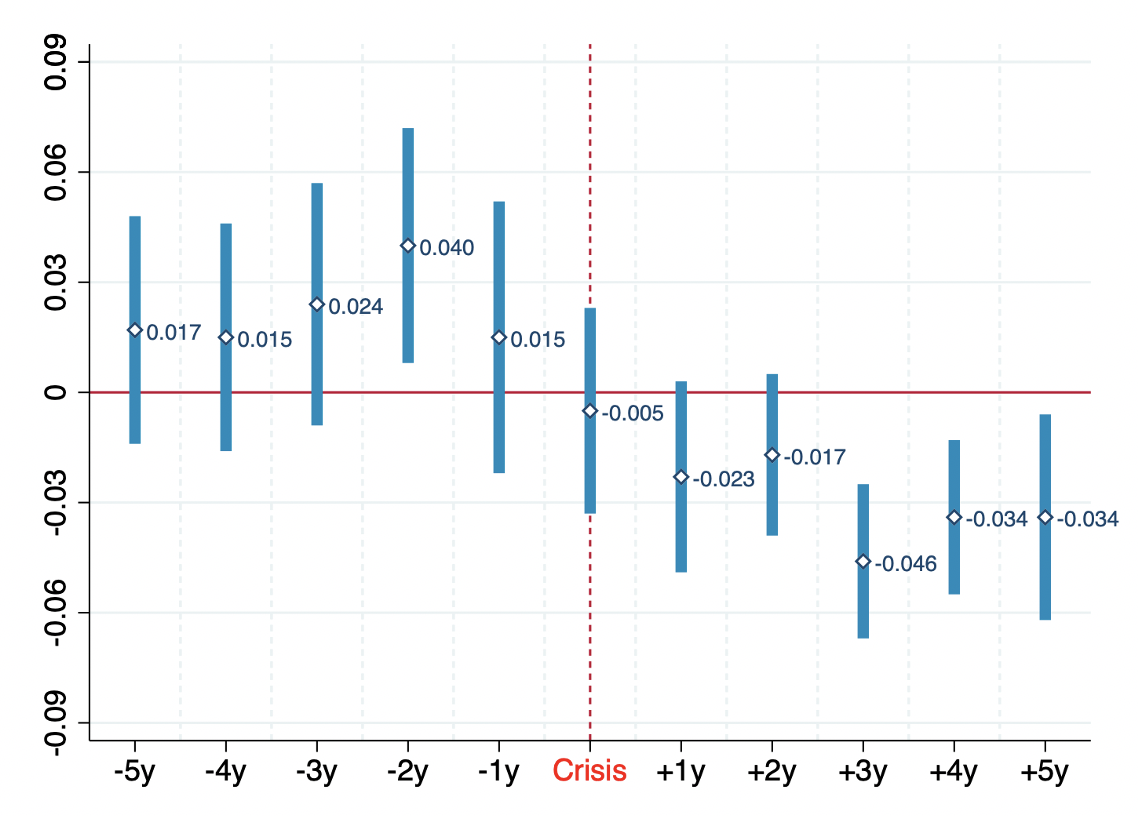

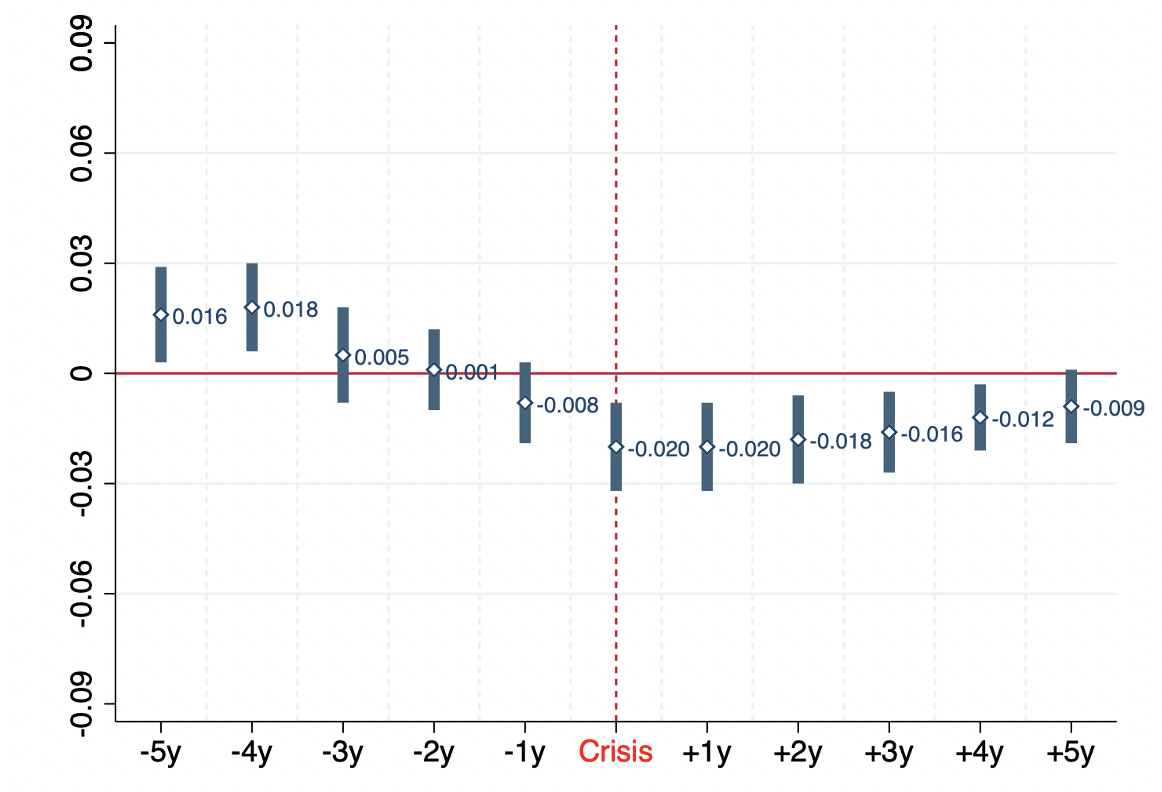

We additionally find that these privately-motivated policies do not immediately follow the financial crises, suggesting that they are not motivated by a need to resolve crises. Figure 2 illustrates this point by separating the effects of private and public interest channels of policymaking estimated within the same specification.

Figure 2 Timeline for the effect of a crisis year (interacted with term limits) on average financial liberalisation

a) Private-interest channel

b) Public interest channel

Notes: The figure plots the estimates for βτ in Panel A and γτ in Panel B, both from the rolling specification in Equation 4 in Saka et al. (2020). Reform database is obtained by merging two subsets of observations from Abiad et al. (2010) and Denk and Gomes (2017). Data on financial crises is obtained from Laeven and Valencia (2018). Political variables are obtained from Cruz et al. (2018). Robust standard errors are clustered at the country level and confidence intervals are at 90% significance level.

On the one hand, the only channel that seems to instantly react to the crisis is the one that is publicly driven. This is consistent with the intuition that the public would require policymakers to immediately respond to the crisis to avert financial doom. Furthermore, the reaction gradually disappears over time, which is again consistent with the idea that these interventions are meant to be only temporary and do not represent permanent changes in a country’s financial policy stance.

On the other hand, the private-interest channel becomes active much later (three years after a crisis), which makes it difficult to categorise these policies as a necessary response to the financial crisis.

Our analysis further shows that privately motivated interventions mainly operate via the extensive margin of policymaking and, more importantly, emerge in different policy domains than those motivated by public interests. In particular, they are reflected in controversial areas such as increasing interest-rate controls and raising barriers to bank entry that are usually associated with rent extraction. They are not reflected in areas such as improving banking supervision or restricting capital controls that are usually associated with financial stability and considered as more aligned with the public interest.

Finally, to illustrate one of the mechanisms behind policymakers’ private interests, we focus on three banking-related policy domains in which we can layout the preferences for incumbent banks: namely, bank entry barriers (proxying incentives to avoid competition), bank privatisation/nationalisation (proxying incentives to be bailed out by the government), and bank supervision (proxying incentives to be monitored by the government).

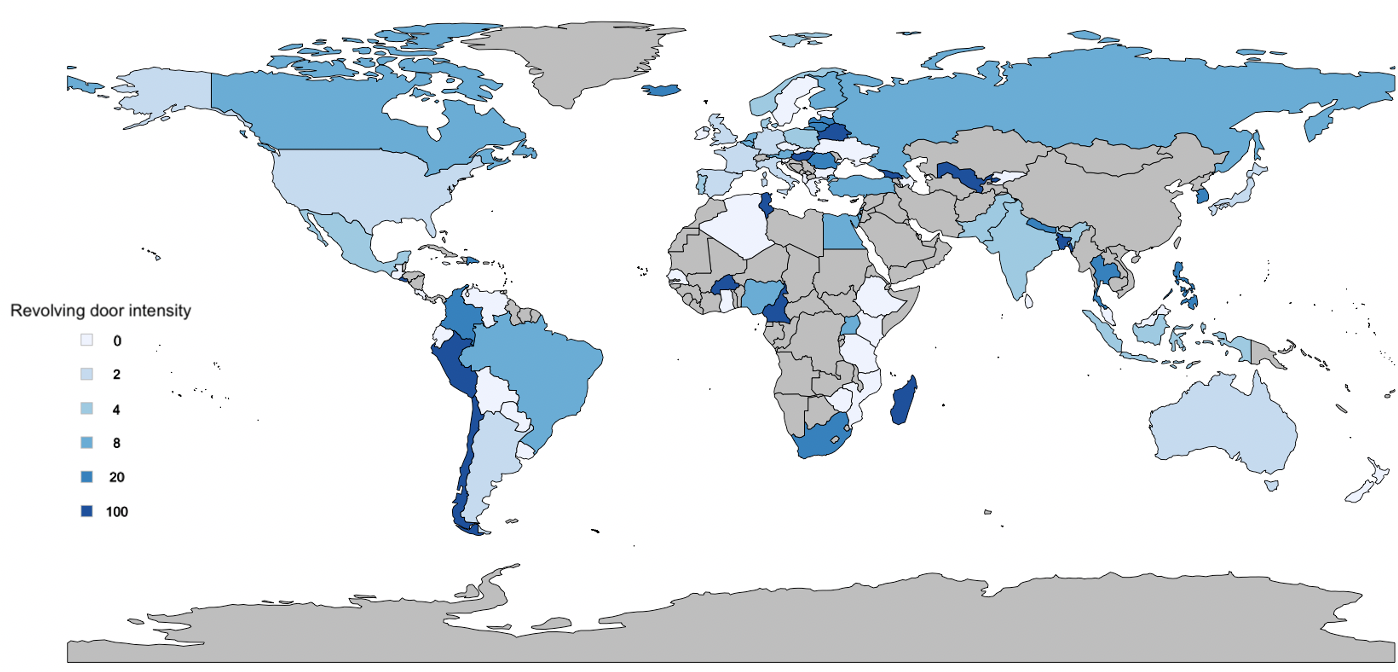

Exploiting the intensity of the revolving doors between political and financial institutions across countries (which we derive from Braun and Raddatz 2010; see Figure 3), we show that term-limited politicians further adjust their policies in ways that would be favourable to incumbent banks when they have a higher chance of pursuing a financial career after leaving politics. This suggests that political executives in their last term advance their private agendas by resorting to financial repression that tends to create rent-seeking opportunities.

Figure 3 Revolving doors between financial and political institutions across the globe: Continuous version

Notes: The figure maps each country depending on the fraction of its politically connected banks, which is the number of banks with at least one former politician on the board of directors divided by the number of banks for which there are data on board members in Bankscope as of 2006. The measures are obtained from Braun and Raddatz (2010).

References

Abiad, A, E Detragiache and T Tressel (2010), “A New database of financial reforms”, IMF Staff Papers 57(2): 281–302.

Braun, M, and C Raddatz (2010), “Banking on politics: When former high-ranking politicians become bank directors”, The World Bank Economic Review 24(2): 234–79.

Chwieroth, J M, and A Walter (2019), “The wealth effect: The middle class and the changing politics of banking crises”, VoxEU.org, 3 June.

Cruz, C, P Keefer and C Scartascini (2018), “Database of political institutions codebook: 2017 update”, Inter-American Development Bank DPI2017.

Dagher, J (2018), “Regulatory cycles: Revisiting the political economy of financial crises”, VoxEU.org, 22 March.

Denk, O, and G Gomes (2017), “Financial re-regulation since the global crisis? An index-based assessment”, OECD Economics Department Working Papers 1396.

Laeven, L, and F Valencia (2018), “Systemic banking crises revisited”, IMF Working Paper 18/206.

Oster, E (2019), “Unobservable selection and coefficient stability: Theory and evidence”, Journal of Business and Economic Statistics 37(2): 187–204.

Reinhart, C (2009), “The economic and fiscal consequences of financial crises”, VoxEU.org, 26 January.

Saka, O, Y Ji and P De Grauwe (2020), “Financial policymaking after crises: Public vs. private interests”, CEPR Discussion Paper 15413.