In advanced modern economies, the economically and politically powerless have little financial power. In the US, for instance, the bottom quarter of the income distribution borrow through short-term loans from pawnshops and payday lenders at rates of around 450% per annum. In contrast, those in the top quartile do so through credit cards at 13–16%. Unlike the poor, the wealthy also have access to long-term credit through home equity loans at rates of around 4%. Indeed, variations in access to financial services constitute a major source of inequality (Demirgüç-Kunt and Levine 2009).

The reason for the disparity in interest rates paid by the rich and poor may seem obvious for anyone familiar with basic economics – the poor are more likely to default, and high interest rates are the price they pay for such higher risk. Yet, implicit in this logic is that financial contracts are enforceable impartially when the borrower is able to pay. The rich pay less for credit because they are relatively unlikely to default and because, if they do, lenders can force repayment through courts whose verdicts are more or less impartial, at least with regard to financial matters.

However, in settings where the courts are biased in favour of the wealthy, their creditors will expect compensation for the risk of being unable to obtain restitution. Lenders will also factor into their calculations that wealthy borrowers expecting the judicial system to be biased in their favour have a greater temptation to default. With respect to interest rates, expected judicial bias can thus counteract the effect of wealth. The former raises the credit cost of the rich, while the latter lowers it. Ironically, in this case the social handicaps of the powerless translate into greater financial power, as manifested through lower borrowing costs.

But when do the powerless actually have financial power, in the sense of paying lower interest rates on loans? The theory described above suggests that, if we are to find such a setting, we should look to a society in which courts are manifestly biased in favour of the powerful. While such societies exist around the developing world today – especially in autocracies – data on credit markets is rarely available in these settings. Instead, we turn to history to test this theory.

In a recent paper, we analyse a data set composed of private loans issued in Ottoman Istanbul during the period 1602–1799 (Kuran and Rubin 2018). This is an ideal empirical context to test whether and when the powerless can have financial power, because Islamic Ottoman courts served all Ottoman subjects through procedures that were manifestly biased in favour of clearly defined groups.1 These courts gave Muslims rights that they denied to Christians and Jews, for example. They privileged men over women. Moreover, because the courts lacked independence from the state, Ottoman subjects connected to the sultan enjoyed favourable treatment.

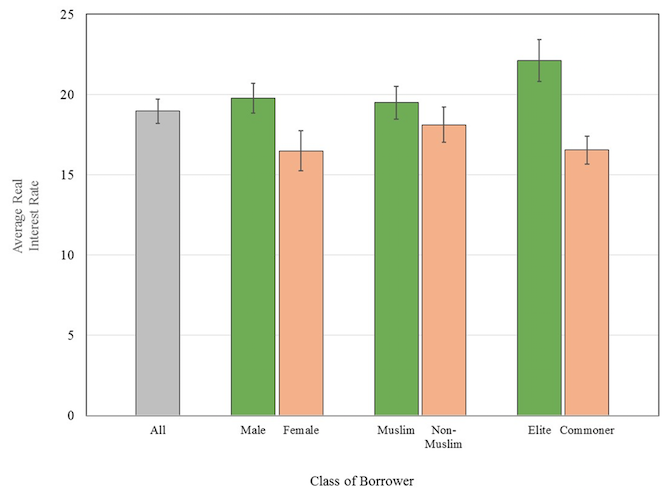

These data suggest that – at least in Ottoman society – the powerless did indeed have financial power (see Figure 1). On average, men paid about 3% higher interest than women, Muslims paid about 1.5% higher interest than non-Muslims, and elites paid about 6% higher interest than non-elites. In a society where the average real interest rate was 19%, these are large inter-group differences. These differences hold regardless of the status of the lender – titled lenders lent at higher rates to other titled borrowers than they did to non-titled borrowers, Muslim lenders charged more to coreligionists than they did to non-Muslims, and male lenders charged other males higher rates than they did to females.

Figure 1 Average real interest rate by class of borrower

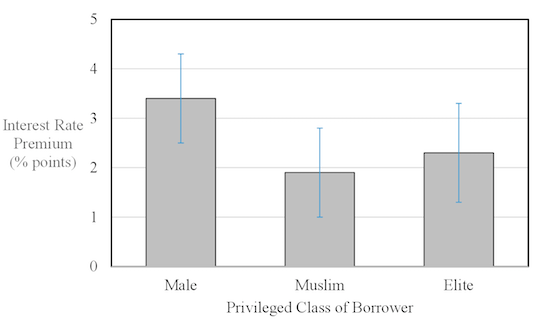

Of course, these differences in real interest rates may simply be artefacts of other loan characteristics. For example, if males took out larger loans (and thus riskier loans, like jumbo mortgages today), had fewer co-signers, or the like, this may explain why they paid higher interest. To address this possibility, we run numerous regressions controlling for all the loan characteristics that are available in the data, including the principal, whether it was a mortgage, the presence of a pawn or co-signer, and whether the lender is a waqf (i.e. an institutional lender). Even after controlling for these features, we find that the powerful still paid a premium in private loan markets. Men paid 3.4% more than women, Muslims paid 1.9% more than non-Muslims, and elites paid 2.3% more than non-elites (see Figure 2).

Figure 2 Interest rate premium for male, Muslim, and elite borrowers (regression coefficients)

With each marker of socioeconomic status that lends itself to quantitative analysis, credit cost differences accord with our theory. Moreover, the differences run in the opposite direction from what is observed in countries whose courts are less biased on financial matters, and if at all, towards the socially disadvantaged. The signs of the key coefficients are always consistent with theoretical predictions, and the magnitudes are generally substantial. If an alternative theory also explains these results, it would have to be consistent with Ottoman institutional history, including the judicial system’s deliberate and open partiality in favour of Muslims, men, and elites. Not only is our explanation couched in a parsimonious theory based on elementary economics, it also matches the historical record. It thus satisfies the two main criteria of solid historical explanation, i.e. grounding in general theory and consistency with observed facts.

Students of the rule of law have long understood that credit costs depend on the enforceability of financial contracts. The credibility of a state’s promises affects the cost of financing public debt. Likewise, our results indicate that the enforceability of private financial commitments influences the cost of private debt. Just as investors induce the bonds of unreliable states to pay high interest rates, so in countries where individual commitments are poorly enforced, rates on private loans tend to be high. The primary insight conveyed here is that intergroup variations in contract enforcement generate systematic differences in private interest rates. Judicially favoured groups pay more for credit precisely because their promises are relatively less credible. Policies that limit the underlying judicial biases will lower the interest rates of the favoured accordingly.

Across the world there are substantial overlaps between the distributions of political power, economic power, and legal power. The richest Americans enjoy vastly disproportionate political clout, as measured by the capacity to influence elections and legislation, and also higher legal power, as measured by the ability to mount a defence in court. But finance is a domain where modern groups with low economic and political power enjoy substantial legal power because of legislation that protects them, to one degree or another, from creditors. An unintended by-product of such legislation is to weaken the credibility of financial commitments by the poor. That is one reason why in advanced economies the poor endure interest rates that exceed by two orders of magnitude those paid by the rich. This must rank among the structural causes of chronic poverty observed in wealthy countries.

Among the big puzzles in comparative economic development is that, in the course of the second millennium, the Middle East went from leader to laggard in many domains (Kuran 2011, Rubin 2017). One basic indicator of the lag involves trust in the courts, and another the persistent prevalence of personal exchange. Where the roots of these problems lie and, more specifically, whether Islamic law was a factor, is a matter of potent controversy. In identifying and quantifying intergroup variations in credit cost, our research provides a novel perspective on the efficiency of governance based on Islamic law. In a nutshell, it suggests that those with the greatest capacity to invest in capital and entrepreneurial activities – the ‘powerful’ – paid the most for credit. This must have retarded economic growth in the region.

References

Demirgüç-Kunt, A, and R Levine (2009), “Finance and Inequality: Theory and Evidence”, Annual Review of Financial Economics 1: 287-318.

Kuran, T (2011),The Long Divergence: How Islamic Law Held Back the Middle East, Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Kuran, T, and J Rubin (2018), “The Financial Power of the Powerless: Socio-Economic Status and Interest Rates under Partial Rule of Law”, Economic Journal 128: 758-96.

Rubin, J (2011), “Institutions, the Rise of Commerce, and the Persistence of Laws: Interest Restrictions in Islam and Christianity”, Economic Journal 121: 1310-39.

Endnotes

[1] Even though Islamic law (Sharia) bans interest, the Ottoman Empire’s Islamic courts permitted it, provided two conditions were fulfilled. The rate had to be ‘moderate’ and, as in Europe in earlier times, it had to be disguised through one of several legal ruses designed to make the payment look like the price of some object (Rubin 2011, Kuran 2011: Chapter 8).