COVID-19 has started to take its toll and it is not yet clear how long it is going to last or how it will end . The impacts of the virus on the lives of households, the economic growth, and the health sector are deemed significant, and an attempt to reverse these negative impacts requires substantial fiscal or monetary resources. The US which itself, to some extent, followed EU-originated initiatives (see Bénassy-Quéré et. al 2020 and Baldwin 2020 for some first and early support designs), has led and outpaced other countries, largely because of its superior position in the international financial system, by unveiling several large-size stimulus packages. The media is awash with the news of the big stimuli by the EU and US, and decisionmakers in many developing countries feel the pressure from an anxious public to follow suit and do the same. Looking at policy responses adopted by many developing countries to contain the impacts of the pandemic, one can see that there is a small-size copy-paste inclination . In some cases, it has even been observed that the ratio of European and American support packages to their GDP is used as an index to assess the quality or the amount of the stimulus plan in a developing or emerging economy. The problem is that this ‘ready-to-wear’ clothing does not fit everyone, and it can cause a lot of problems when worn on the wrong body. Countries may be pushed to the brink of debt, inflation or banking crises, among other problems.

The framework

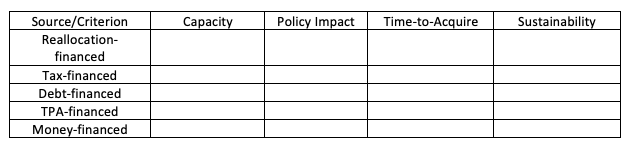

Deficit financing approaches are usually limited to tax-based, expenditure-based, and debt-based mechanisms. In addition to these three types of solutions, we could consider a role for the transfer of public assets by disposing public non-financial assets or divesting government shares in public enterprises. Finally, we could consider the monetisation of deficit, also known as ‘helicopter money’ (Gali 2020). For each of these solutions, we can define four different ’policy space’ determinants or policy selection criteria. To begin with, there should be a capacity or ‘potential’ to generate resources so that it does not go far beyond the experimental, comparative or theoretical norms. For instance, an undertaxed, resource-rich economy may have a considerable tax policy space (also known as tax-gap which is defined as the difference between the amount of tax that should—in theory, or comparatively—be collected and what is actually paid). Such a country can generate a big chunk of tax revenue before it hits the global or regional ‘norm’. The second criterion deals with the impact analysis of the policy, and what influence it could have on the other sectors, or the economy as a whole. This criterion can generally be analysed through a macroeconomic model or using other economic analytical frameworks. For a detailed discussion about when some of the deficit-financing mechanisms work and when they don’t work, see Alesina et al. (2019). The third criterion is the amount of time needed to generate the resources, while a fourth would be the sustainability issues related to the policy, and whether it can be done repeatedly in the medium or long term. These policies and relevant criteria can be displayed and check-boxed in a simple table of policy options. This would show if a proposed policy (i) has enough capacity to generate the needed resources, (ii) whether the policy impact appropriately fits the current situation of the economy, (iii) whether the time needed to generate the resource by applying the policy is short enough, (iv) and finally, whether the policy could be extended or used in a repetitive mode.

Table 1 Policy options template

Notes: Fill with: OK or Not-OK (O/N)

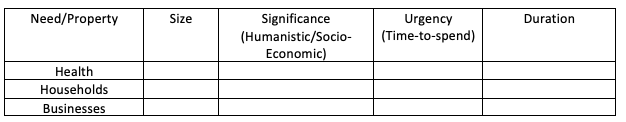

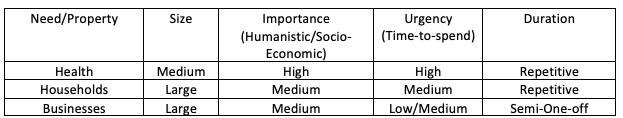

In addition to analysing the policy options with regards to the resource generating mechanisms, there should be an analysis from the expenditure (spending) point of view. An epidemic or pandemic, as a health emergency, usually impacts the health sector, the households (i.e. the labour force), and the businesses. The impact targets can also be expanded to include more detailed ‘strike sites’ (Baldwin 2020). Each spending target should be assessed based on (i) the amount of the resources needed, (ii) the significance or importance of the spending (from the health perspective or the economic vitality point of view), (iii) its urgency (can spending be postponed or should it be spent immediately) and finally (iv) the duration of the spending and for how long it is supposed to continue.

Table 2 Template for resource needs and spending properties

Notes: Fill with: Size: Small to Large, Urgency: Low to High, Significance: Low to high, Urgency: Low to high, Duration: Repetitive or one-off or semi-one-off

Framework in action

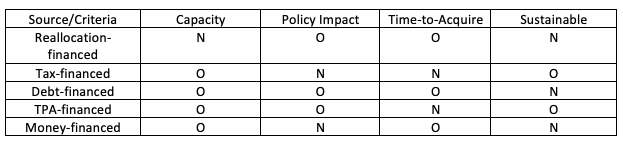

Table 3 is a typical policy options template filled in for a sample country which has a rigid budget, highly undertaxed economy (hint: with near-zero or recessionary growth rate), sizable (hint: but with low/non-liquid) portfolio of public assets, benefits from recently deepened financial markets (hint: public debt may be unsustainable if the current pace of debt accumulation continues in the medium term), and finally enjoys a quasi-stable banking system (hint: with high double-digit inflation). Table 4 is the completed version of the table of needs and policy properties for the same sample country.

Table 3 Policy options template completed for a sample country

Table 4 Resource needs and spending properties for a sample country

Based on the analysis of the sample economy, one can argue that to mitigate the economic impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic, you should not rush to push the print button in the first step because it may worsen the inflation (unless the amounts are not big enough to shoot the already inflation-hit economy into hyper-inflation). Instead, try to use debt issuance. Also, if your needs are repetitive and not very urgent, do not link those needs to the unsustainable debt issuance, and instead, try options—or a mix of options—like tax-based mechanisms (only in the circumstances where the tax-gap filling process would not cause a high recessionary pressure or it is assumed to be gradual) and asset transfer programs. There are also other procedural aspects of the spending side, the most important of which is the identification issue - make sure your spending can reach the right target. Otherwise, you may be just strengthening the already strong target at the expense—or by inflation tax of—needy households and businesses.

Conclusion

Do not imitate the US behaviour if you don’t have enough policy space (i.e. if the capacity, the impact, the time-to-acquire, and the sustainability criterion of the selected policy are not favourable) and if the monetarisation of your virus-caused health/economic deficit can lead to a worsening of the already dire situation. Instead, try to identify your needs and match those needs to a set of broader and available policy options (based on the properties of your needs and the criterion of your policies). Then, select a policy or a menu of policies that best suit your needs, without unintentionally deteriorating the situation.

References

Alesina, A, C Favero and F Giavazzi (2019), Austerity: When it Works and When it Doesn't, Princeton University Press.

Baldwin, R (2020), "Keeping the Lights On: Economic Medicine for a Medical Shock", VoxEU.org, 13 March.

Bénassy-Quéré, A, R Marimon, J Pisani-Ferry, L Reichlin, D Schoenmaker and B Weder di Mauro (2020), “COVID-19: Europe needs a catastrophe relief plan”, VoxEU.org, 11 March.

Gali, J (2020), "Helicopter money: The time is now", VoxEU.org, 17 March.

Gali, J (2020), "The Effects of a Money-Financed Fiscal Stimulus", Journal of Monetary Economics, forthcoming.

Endnotes

1 https://blogs.imf.org/2020/03/30/europes-covid-19-crisis-and-the-funds-response/

2 https://apnews.com/67ac94d1cf08a84ff7c6bbeec2b167fa

3 https://www.theatlantic.com/health/archive/2020/03/how-will-coronavirus-end/608719/

4 https://www.imf.org/en/Topics/imf-and-covid19/Policy-Responses-to-COVID-19