While arguments against reserve accumulation often point to the cost of exchange rate interventions, these costs may have been overstated: they depend critically on how reserves are funded, a decision, in turn, related to the nature of the intervention (e.g. Levy Yeyati and Gomez 2019, Sosa-Padilla and Sturzenegger 2021). The recent literature has centred primarily on two motives: a precautionary ‘self-insurance’ motive aimed at building a reserve war chest to buffer the economy against dollar liquidity shortages (Obstfeld et al. 2008), and a ‘leaning-against-the-wind’ motive aimed at smoothing out the exchange rate impact of global commodity and financial cycles (Daude and Levy Yeyati 2014). In a recent paper (Levy Yeyati and Gómez 2022), we compare the costs under the two intervention types and find significant differences.

Under self-insurance, reserve accumulation increases both foreign exchange assets and liabilities as if reserve assets were purchased with the proceeds of the primary issuance of foreign currency-denominated sovereign paper, and the marginal fiscal cost of carrying reserves should be proportional to the cost of the new debt net of the returns on reserves, roughly equal to the sovereign credit risk spread plus the term premium associated with the duration mismatch, if any (Jeanne and Ranciere 2011, Rodrik 2006).

Under leaning-against-the-wind, intervention entails a change in the relative supply of local currency assets, thus requiring that reserves be funded by issuing local currency-denominated liabilities. As a result, the central bank pays the local-to-foreign currency interest rate differential and receives valuation gains due to changes in the nominal exchange rate. In other words, the other side of a ‘carry trade’.

It follows that a key question underlying the costs of reserves is how reserves are funded.

How are reserves built up?

Perhaps the simplest way to examine how reserve stocks are funded is by looking at how the government's investment position changes based on the balance of payments flows.

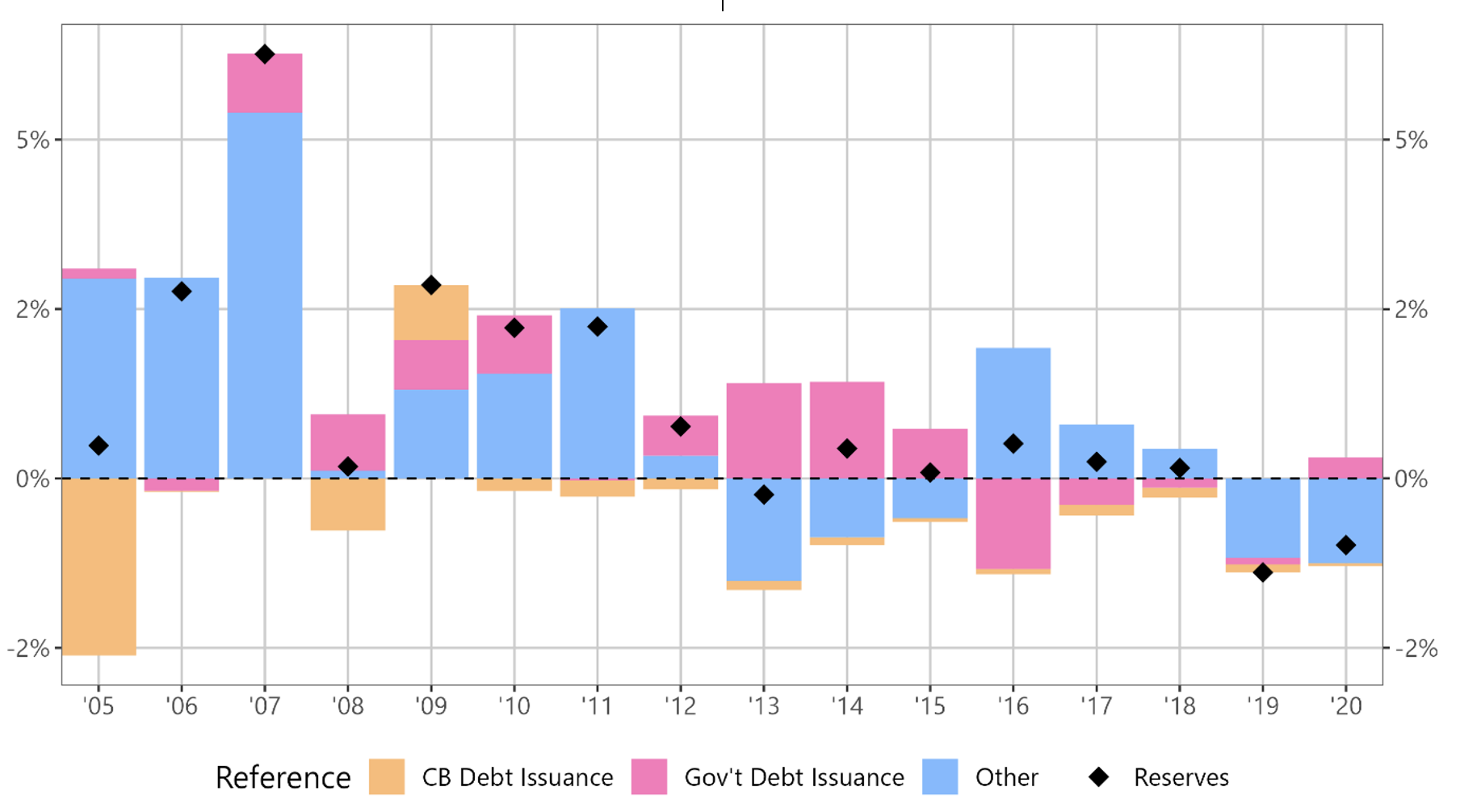

Figure 1 exemplifies the case of Brazil, where changes in reserves are primarily associated with the current account balance plus the private side of the financial account (denoted by ‘Other’), that is, the flows of the balance of payments not covered by dollar debt-issuance.

Figure 1 How are reserves built up? A reading from the balance of payments

Brazil (% of GDP)

Note: ‘Reserves’ are the annual change in the stock of official foreign exchange reserves, ‘CB Debt Issuance’ and ‘Gov’t Debt Issuance’ are changes in the net foreign debt position of the central bank and the central government, respectively. ‘Other’ are the remaining flows, different than dollar-debt-issuance, that cause reserve accumulation.

Source: Authors’ estimates based on data from the IMF’s Balance of Payments Statistics and The World Bank Group.

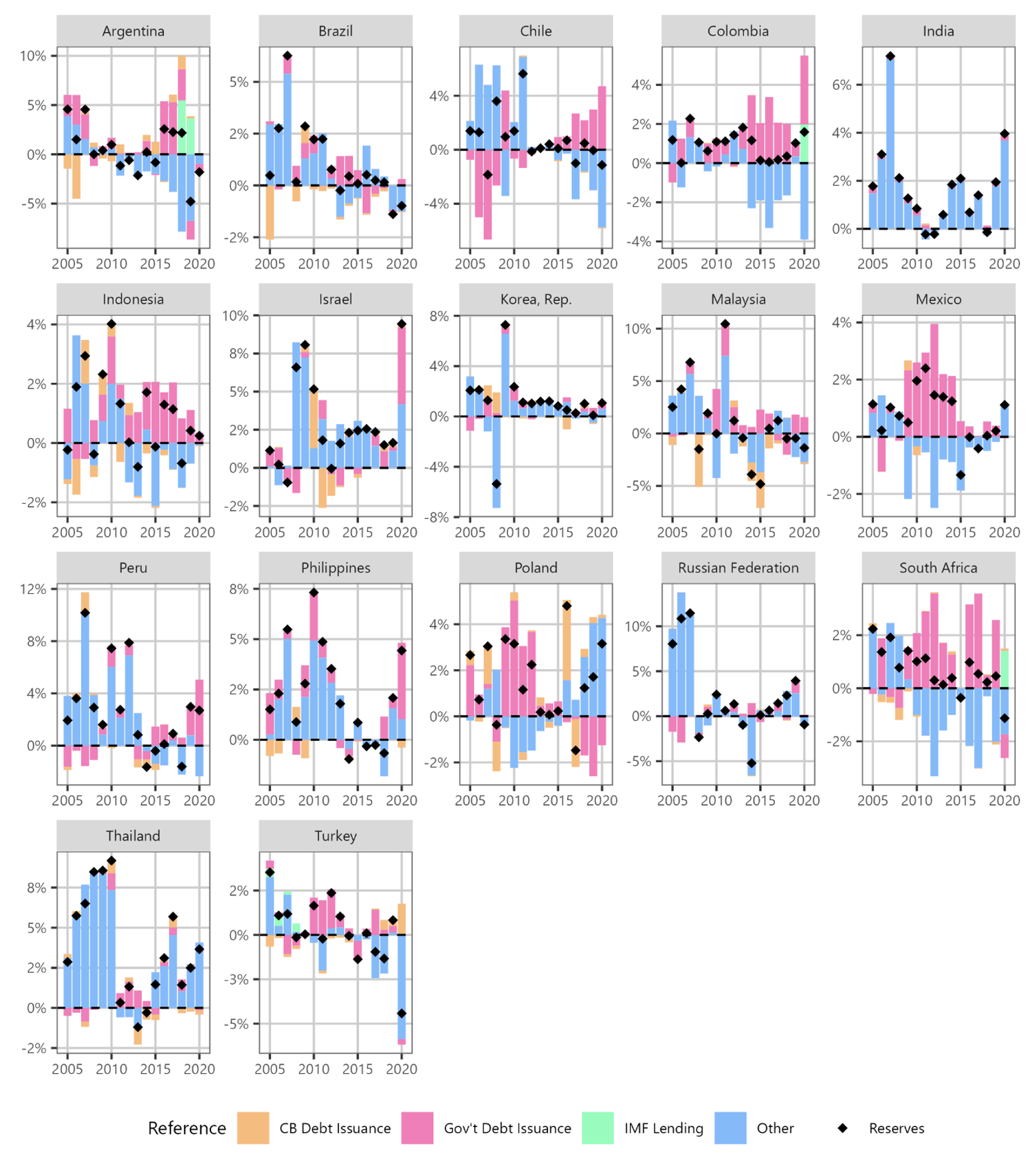

From a fiscal perspective, it is natural to consider the three operations (sovereign debt issuance, foreign exchange sales by the public sector, and sterilised reserve purchases) as one. Reassuringly, even in this case, data for the emerging market sample indicates that the carry-trade view tends to prevail (Figure 2).

Figure 2 How are reserves built up? A reading from the balance of payments

(selected countries, % of GDP)

Note: ‘Reserves’ are the annual change in the stock of official foreign exchange reserves, ‘CB Debt Issuance’ and ‘Gov’t Debt Issuance’ are changes in the net debt foreign position (assets minus liabilities) of the central bank and the central government, respectively. ‘IMF Lending’ are loan disbursements. ‘Other’ are the remaining flows, different than dollar-debt-issuance, that cause reserve accumulation.

Source: Authors’ estimates based on data from the IMF’s Balance of Payments Statistics and The World Bank Group.

The cost of leaning against the wind

A leaning-against-the-wind central bank accumulates foreign-currency reserves against local-currency debt. This mirrors the position of a carry trader who shorts the foreign currency betting on further appreciation. In the absence of Tobin-type taxes or restrictions on capital mobility, the loss of the central bank should equal the profit of the carry net of (typically minor) transaction costs –essentially, the profit of a reverse carry trade position.

Under self-insurance, because reserves assets are often shorter than the foreign-currency liabilities used to fund them, a term premium should be added to the credit risk premium in the computation. By contrast, the local currency instruments used to sterilise reserve purchases (local Treasuries, central bank facilities) are typically shorter than reserve assets, so a term premium should be subtracted from the carrying cost (for details, see Levy Yeyati and Gómez 2022).

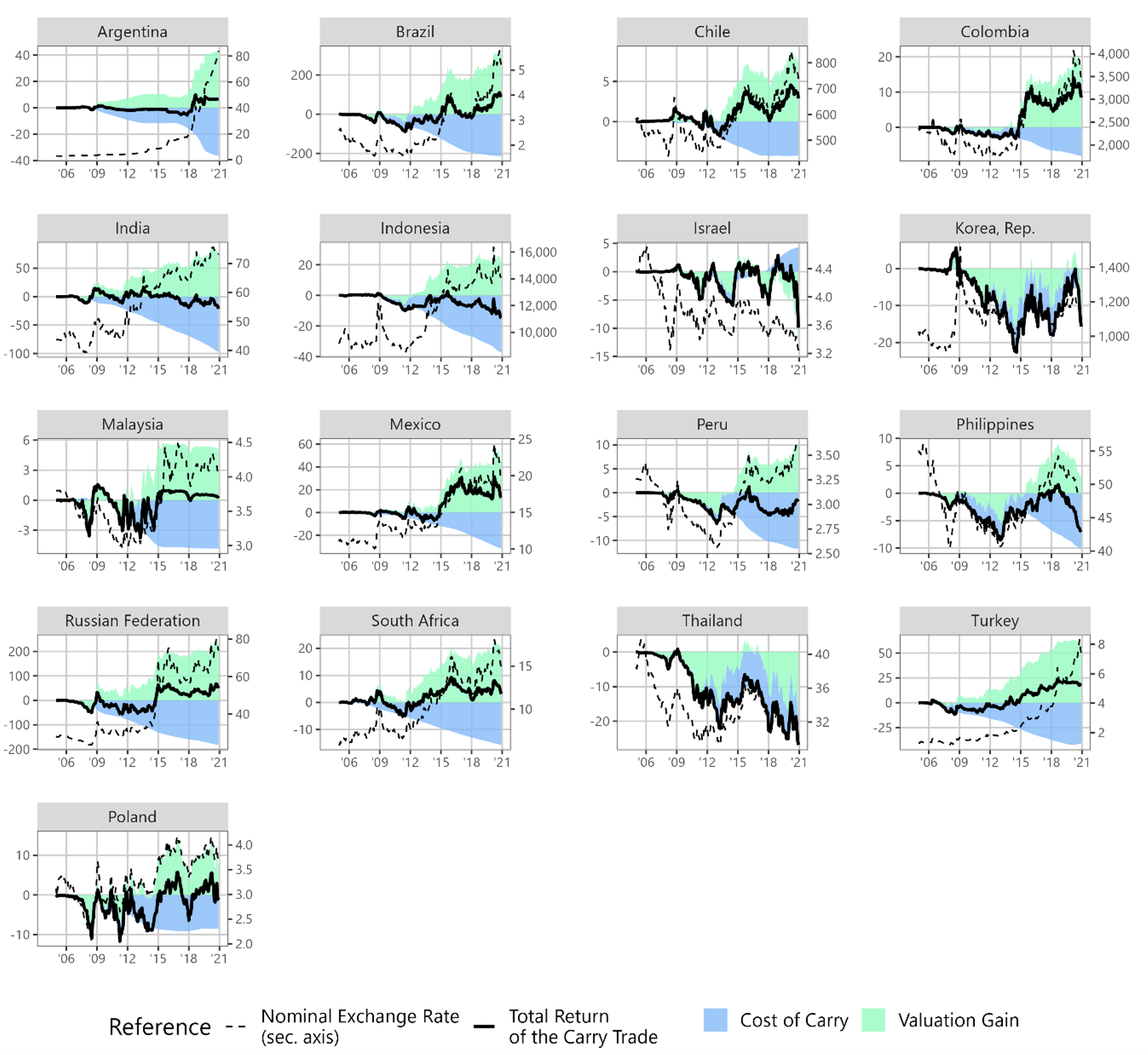

To illustrate, we estimate the realised costs of spot central bank intervention from the beginning of 2005. Specifically, we assume that, starting in January 2005, at the beginning of each month, the central bank purchases international reserves, funded by the issuance of local currency debt, for an amount equal to the change in the reserve stock during the month —where the latter is corrected for interest income assuming a continuous income flow associated with an annualised return equal to the yield on two-year Treasury notes, as well as for variations in the US dollar value of the reserve currency basket.

We compute the profit and loss by the sum of the local-to-foreign currency interest rate differential (henceforth, the ‘Cost of Carry’, which is typically positive, hence a cost from the perspective of the holder of international reserves) and valuation changes (for the central bank standpoint, a loss whenever the local currency appreciates and a profit when it depreciates; henceforth, the ‘Valuation Gain’).

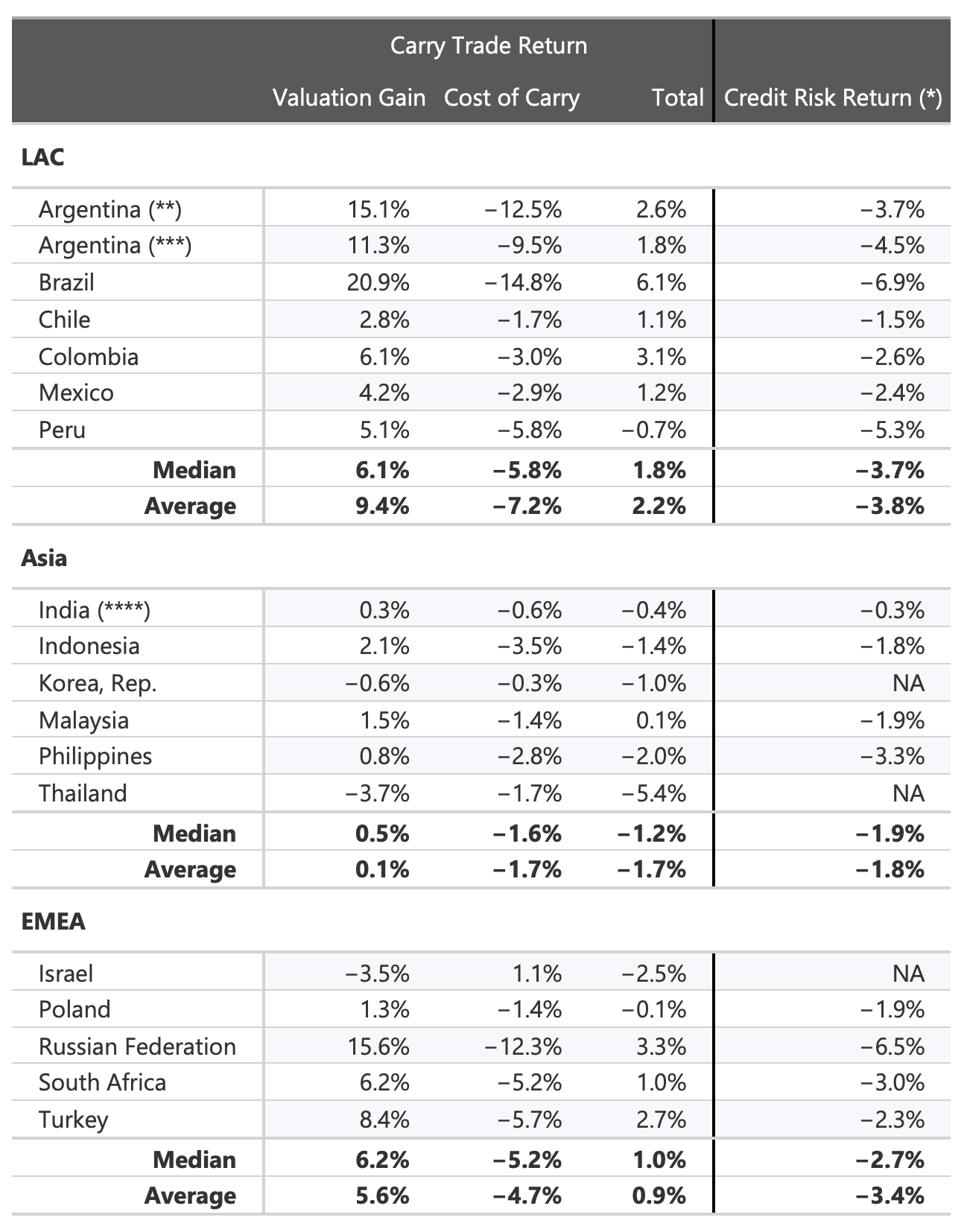

Figure 3 shows the evolution of the profit and loss, and Table 1 reports the cumulative fiscal cost. As can be seen, once properly normalised by GDP, the cost of intervention is minor, or even reverts to a profit. In South-East Asia, modest but still positive interest rate differentials outweigh near-zero valuation gains due to stable-to-stronger currencies for a total average cost of 1.7% of GDP. However, for the rest of the sample large valuation gains more than offset the large interest rate carry to yield average intervention ‘gains’ of 2.2% and 0.9% of GDP, respectively. The last column of Table 1 reports our estimations based on the credit-risk view and shows that they tend to exceed those based on the carry-trade view.

Figure 3 Cumulative monthly returns as measured by the carry-trade view

(Left axis: $ billions; right axis: local currency unit per $)

Source: Reserves and Nominal Exchange Rates are from IMF’s International Financial Statistics, and carrying rates are three-month implied yields derived from the covered interest rate parity condition built by Bloomberg, L.P. Carry rate of Argentina was built as the difference between three-month central bank papers ('Lebacs') and US Treasury rates of the same maturity up to 2018, then as the difference between the rate on the one-month central bank paper ('Leliq') and US Treasury rates of the same maturity. Data on Argentina is from Argentina’s central bank, and data on US Treasuries are from the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis.

Table 1 Carry-trade and the credit-risk views on the cost of reserves

Cumulative 2005-2020 returns as a % of 2020 GDP (positive = gain)

Note: (*) Proxied by Emerging Market Bond Index + US Term Premium (2y-5y). (**) Excludes periods with foreign exchange restrictions in 2011-2015 and 2019-2020. (***) Full sample. ‘LAC’ stands for Latin America and the Caribbean, and ‘EMEA’ for Eastern European, the Middle East, and Africa.

Source: The World Bank Group, Bloomberg, and The Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis.

A final comparison sheds light on the nature and motives of intervention, based on the premise that, if the central bank intervenes countercyclically, it tends to buy low and sell high, overperforming a constant-size carry trade that keeps the notional constant over the whole period. Table 2 shows that, with a few notable exceptions (Argentina, Turkey, Russia, and South Africa), the central bank consistently outperforms the constant-size trader, in line with the benefits expected from countercyclical interventions.

Table 2 Compound average growth rate of returns of two trades: One following a carry-trade that mimics a leaning-against-the-wind central bank, and the other with a constant notional of $100 over the whole period, 2005-2020

(positive = gain)

Note: (*) and (**) Excludes and includes periods with foreign exchange restrictions in 2011-2015 and 2019-2020. respectively.

Source: Same as Figure 3.

In sum, while realised intervention costs depend crucially on the timing and nature of the intervention and tend to vary considerably over the cycle, the conventional view that exchange rate intervention and international reserve accumulation are costly due to wide sovereign spreads and heavy quasi-fiscal losses substantially overstates the cost of intervention under a leaning-against-the-wind policy.

References

Adler G, Tovar C E (2011), “Foreign Exchange Intervention: A Shield Against Appreciation Winds?”, IMF Working Paper.

Daude, C and E Levy Yeyati (2014), “'Leaning against the wind’: Exchange rate intervention in emerging markets works”, VoxEU.org, 1 September.

Jeanne O, Ranciere R (2011), “The Optimal Level of International Reserves for Emerging Market Countries: A New Formula and Some Application”, Economic Journal 121(555): 905–930.

Levy Yeyati E (2011), “Cost of Reserves”, Economics Letters 100 (2008): 39-42.

Levy Yeyati E and J F Gomez (2019), “The Cost of Holding Foreign Exchange Reserves”, Center for International Development Working Paper Series, Harvard University.

Levy Yeyati, E and J F Gomez (2022), “Leaning-against-the-wind Intervention and the “Carry-Trade” View of the Cost of Reserves,”, Red Nacional de Investigadores en Economía Working Paper (forthcoming in Open Economies Review).

Obstfeld, M, J C Shambaugh and A M Taylor (2008), “Reserve accumulation and financial stability”, VoxEU.org, 11 October.

Rodrik D (2006), “The Social Cost of Foreign Exchange Reserves”, International Economic Journal 20(3): 253–266.

Sosa-Padilla, C and F Sturzenegger (2021), “Does it matter how central banks accumulate reserves? Evidence from sovereign spreads”, NBER Working Paper 28973.