When child welfare workers determine that a child was abused or neglected, they must make a drastic decision to either have the child continue living in the home or place them in foster care. Despite the life-altering stakes, there is little evidence of the long-term consequences of the difficult trade-off between family preservation and child safety. On the one hand, keeping children in a harmful home environment could lead to worse adult outcomes. On the other, separating children from their families could lead to trauma and instability in their lives.

A surprisingly large percentage of children in the US experience foster care at some point during their childhood. As many as 5% of all children, and up to 9% of Black children and 11% of American Indian and Alaska Native children, are placed in foster care at some point by age 18 (Yi et al. 2020). Particularly in light of the dramatic increase in foster care placements attributed to the opioid epidemic (Cutler and Glaeser 2021, Dallman 2020, Evans et al. 2022, Hou 2022, Maclean et al. 2020, Mulligan 2021), it is critical to understand the effects of foster care.

In a recent paper (Baron and Gross 2022), we estimate the causal effect of foster care placement on adult crime. There is a well-documented correlation between foster care and crime. For example, close to one-fifth of the prison population in the US is comprised of former foster children (Bureau of Justice Statistics 2016) and about 70% of youth who exit foster care as legal adults are arrested at least once by age 26 (Courtney et al. 2011). Decades of research also show a positive association between foster care placement and criminality (Yang et al. 2017, 2021), and the media often cites a ‘foster care-to-prison pipeline’ (Amon 2021, Trivedi 2020). Yet these statistics do not capture whether foster care causes crime because children placed in foster care differ in many ways from those not placed.

We assembled a detailed dataset linking administrative child welfare and adult criminal justice records in Michigan to understand the impacts of foster care on later-in-life crime. We study nearly 120,000 child welfare investigations involving children ages 6 to 16 between 2008 and 2016. We isolate the causal effect of foster care by exploiting a feature of child welfare investigations in Michigan that mirrors random assignment: investigators within a local field office are assigned to children’s cases based on who is next on a list, not for reasons specific to the child or family. Investigators also have discretion over whether to recommend placement. These decisions are in part subjective, and some investigators are stricter than others. We compare the outcomes of children who by chance are assigned a strict investigator and placed in foster care to the outcomes of children who are assigned a more lenient investigator and are not placed.

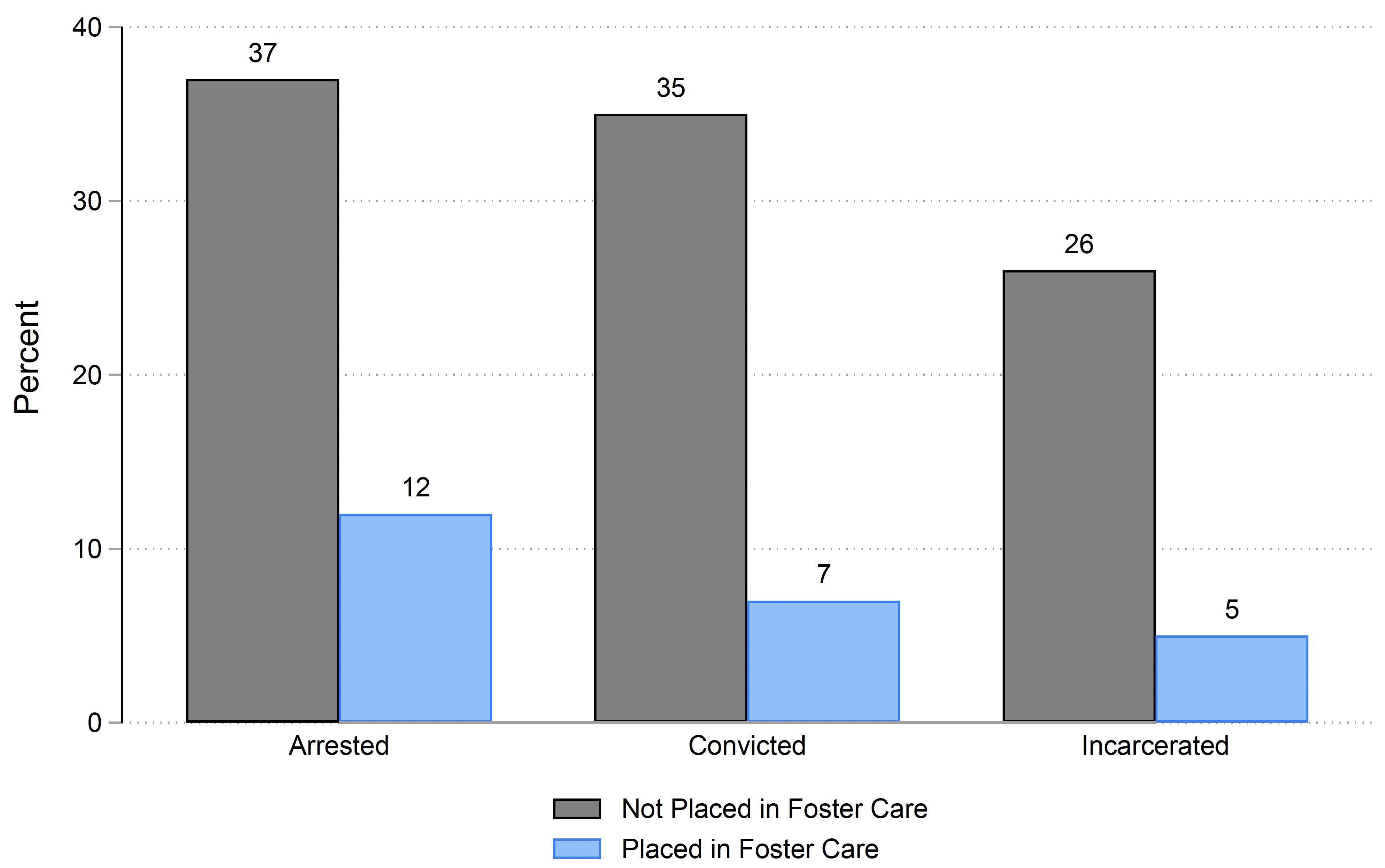

The study finds that foster care placement reduced later-in-life crime (Figure 1). More than one-third of children who were not placed were arrested by age 19 (37%), compared to just 12% of children who were placed in foster care. Likewise, children who were placed in foster care were 28 percentage points less likely to be convicted by age 19 (35% compared to 7%) and 21 percentage points less likely to be incarcerated by age 19 (26% compared to 5%).

Figure 1 The effects of foster care placement on crime by age 19

Note: The differences in outcomes are statistically significant at the 5% level.

We also explored whether foster care reduced adult crime more for certain groups of children. Foster care appeared to reduce adult crime more for male than female children, and for younger children (ages 6 to 11) than older youth (ages 12 to 16). We find similar effects for White, Black, and Hispanic children. Lastly, suggestive evidence indicates that children who were likely the most severely abused or neglected benefited the most from placement. In contrast, we find no evidence of impacts for children who were likely less severely maltreated.

Who do these findings apply to?

The vast majority of child welfare investigations involve children for whom foster care placement is not warranted. The findings in this study represent the effects of placement only for children at the margin of foster care – that is, ‘candidates’ for foster care, or children for whom some investigators might have recommended placement while others would not have. Among candidates who were placed, we find that nearly all were initially placed in a family home with relatives or an unrelated family as opposed to a group home, and most experienced relatively stable placements, as measured by the number of different placement settings once in foster care. They tended to have relatively short stays in foster care of about one to two years after which more than four in five reunified with their biological family.

What are the channels through which foster care reduces adult crime?

We explore mechanisms for why foster care reduces adult crime by first examining impacts on other indicators of child wellbeing. We find that foster care protects children from subsequent abuse and neglect. Children who are placed are considerably less likely to be confirmed as victims of maltreatment in the future, even years after they exit foster care.

We also see improvements in a range of other short- and medium-term wellbeing measures. Linking to administrative records from Michigan’s K-12 public school system and nationwide postsecondary enrolments, we find that foster care substantially reduces absences from school, improves math test scores, and appears to increase the likelihood of high school graduation and college enrolment. We also examine impacts on children’s behaviour through data on juvenile detention spells and find that placement reduces the likelihood of being held in a juvenile detention centre.

How did foster care placement improve these intermediate outcomes?

We find evidence that birth parents make improvements while their children are temporarily in foster care. Nearly all children at the margin of foster care placement have short stays in foster care (one to two years) after which more than 80% reunify with their birth parents. By examining the time pattern of impacts on children’s outcomes, we show that the gains from foster care emerge after most children reunify and persist thereafter. In addition to these trends, there are institutional reasons to believe that foster care could lead birth parents to make improvements. After removal, birth parents work closely with social workers and receive fully funded services to address challenges in their lives, such as substance abuse treatment or counselling. A judge must also approve that it is safe for families to reunify. Accordingly, we find that birth parents whose children are placed are less likely to abuse or neglect children in the future.

Key takeaways for public policy

The results of this study are especially relevant because of the historic changes to federal policy introduced in the Family First Prevention Services Act of 2019. A main goal of this bipartisan legislation is to keep families intact and reduce foster care caseloads. To do so, it allows states to redirect up to $8 billion in federal funds from foster care and adoption services toward evidence-based prevention-focused programmes and services.

We find that abused and neglected children who were not placed in foster care are more likely to be involved with the adult criminal justice system relative to those who were placed. Thus, our results indicate that safely reducing foster care caseloads will require better efforts to ensure child wellbeing in the home.

Yet, child welfare agencies need not shoulder the burden alone. Studies show that broader social policies, such as a strong social safety net, can also reduce child abuse and neglect (Aizer et al. 2016, Berger et al. 2017, Raissian and Bullinger 2017). To meet the federal goal of safely reducing foster care caseloads, identifying what works to promote child wellbeing while keeping families intact is a crucial frontier for policy and research.

References

Aizer, A, S Eli, J Ferrie and A Lleras-Muney (2016), “The long-run impact of cash transfers to poor families”, American Economic Review 106(4): 935–71.

Amon, E (2021), “New Washington laws aim to interrupt foster care-to-prison pipeline”, The Imprint, 9 August.

Baron, E J, and M Gross (2022), “Is there a foster care-to-prison pipeline? Evidence from quasi-randomly assigned investigators”, NBER Working Paper 29922.

Berger, L M, S A Font, K S Slack and J Waldfogel (2017), “Income and child maltreatment in unmarried families: Evidence from the earned income tax credit”, Review of Economics of the Household 15(4): 1345–72.

Bureau of Justice Statistics (BJS) (2016), Survey of prison inmates.

Courtney, M, A Dworsky, A Brown, C Cary, K Love, V Vorhies and C Hall (2011), “Midwest evaluation of the adult functioning of former foster youth: Outcomes at age 26”.

Cutler, D, and E Glaeser (2021), “Understanding the opioid epidemic: When innovation fails”, VoxEU.org, 12 July.

Dallman, S (2020), “The effect of opioid abuse on child out-of-home placements”, working paper.

Evans, M F, M C Harris and L M Kessler (2022), “The hazards of unwinding the prescription opioid epidemic: Implications for child maltreatment”, American Economic Journal: Economic Policy, forthcoming.

Hou, C (2022), “The opioid crisis and foster care dynamics”, working paper.

Maclean, C, J Mallatt, C J Ruhm and K Simon (2020), “A review of economic studies on the opioid crisis”, VoxEU.org, 20 December.

Mulligan, C (2021), “Deaths of despair and the incidence of excess mortality in 2020”, VoxEU.org, 28 January.

Raissian, K M, and L R Bullinger (2017), “Money matters: Does the minimum wage affect child maltreatment rates?” Children and Youth Services Review 72: 60–70.

Trivedi, S (2020), “Police feed the foster care-to-prison pipeline by reporting on Black parents”, NBC News, 30 July.

Yang, J, E C McCuish and R R Corrado (2017), “Foster care beyond placement: Offending outcomes in emerging adulthood”, Journal of Criminal Justice 53: 46–54.

Yang, J, E C McCuish and R R Corrado (2021), “Is the foster care-crime relationship a consequence of exposure? Examining potential moderating factors”, Youth Violence and Juvenile Justice 19(1): 94–112.

Yi, Y, F R Edwards and C Wildeman (2020), “Cumulative prevalence of confirmed maltreatment and foster care placement for US children by race/ethnicity, 2011–2016”, American Journal of Public Health 110(5): 704–9.