Governments spend substantial amounts on active labour market programmes aimed at improving the employability and earning capacity of the unemployed. One of the most prevalent types of active labour market programmes are training programmes (in traditional classrooms or on the job) that provide unemployed individuals with general skills or specific occupational skills to enhance their productivity and employability. Many individuals, however, lack basic soft skills such as motivation, career aspirations, and interpersonal skills that are needed to transition from welfare to work and persevere in employment – skills that strongly predict labour market success.

Indeed, a growing literature in economics and other social sciences stresses the importance of soft skills for human capital formation and labour market success (Heckman et al. 2006, Deming 2017, Aghion et al. 2020). Yet, scientific evidence on the possibility of improving these skills, especially among the adult population, is limited, and little is known about the impact of such an improvement on labour market outcomes and welfare dependence.

In a recent paper (Schlosser and Shanan 2022), we provide experimental evidence on whether it is possible to develop or enhance soft skills and improve the labour market outcomes of unemployed income support claimants. Using a large-scale randomised control trial, we evaluate the effectiveness of an Israeli active labour market programme that focused on fostering work-related soft skills such as motivation, work self-efficacy, self-esteem, and interpersonal skills. Individuals who submitted new income support claims and a fraction of existing claimants in the welfare system were randomised into treatment and control groups in each of the 14 employment offices participating in the experiment. Randomisation took place on a weekly basis within each employment office separately for the incoming flow of jobseekers (i.e. new claimants) and the stock of current jobseekers (the existing pool of claimants). Individuals assigned to the treatment group received individual coaching and participated in therapeutic group workshops for two to seven months, as well as receiving job search assistance. Our study examines the effects of the programme based on the sample of 6,151 individuals who were randomly allocated to the treatment and control groups during the first year of the programme implementation.

Our study is related to a large literature that evaluates the effects of active labour market programmes (see recent reviews by Greenberg et al. 2003, Kluve 2010, Crépon and van den Berg 2016, Card et al. 2018, and Levy Yeyati et al. 2019). Evidence on the effectiveness of these programmes is still mixed. Moreover, evidence on the effectiveness of active labour market programmes that focus on enhancing soft skills is scarce. A notable exception is Barrera-Osorio et al. (2020), who find positive employment and wage effects from a programme implemented in Colombia among 663 jobseekers that combined training in both technical and soft skills. Our study complements and extends their findings by providing experimental evidence based on a large-scale randomised control trial that focused exclusively on soft skills training.

Programme effects on labour market outcomes and welfare dependence

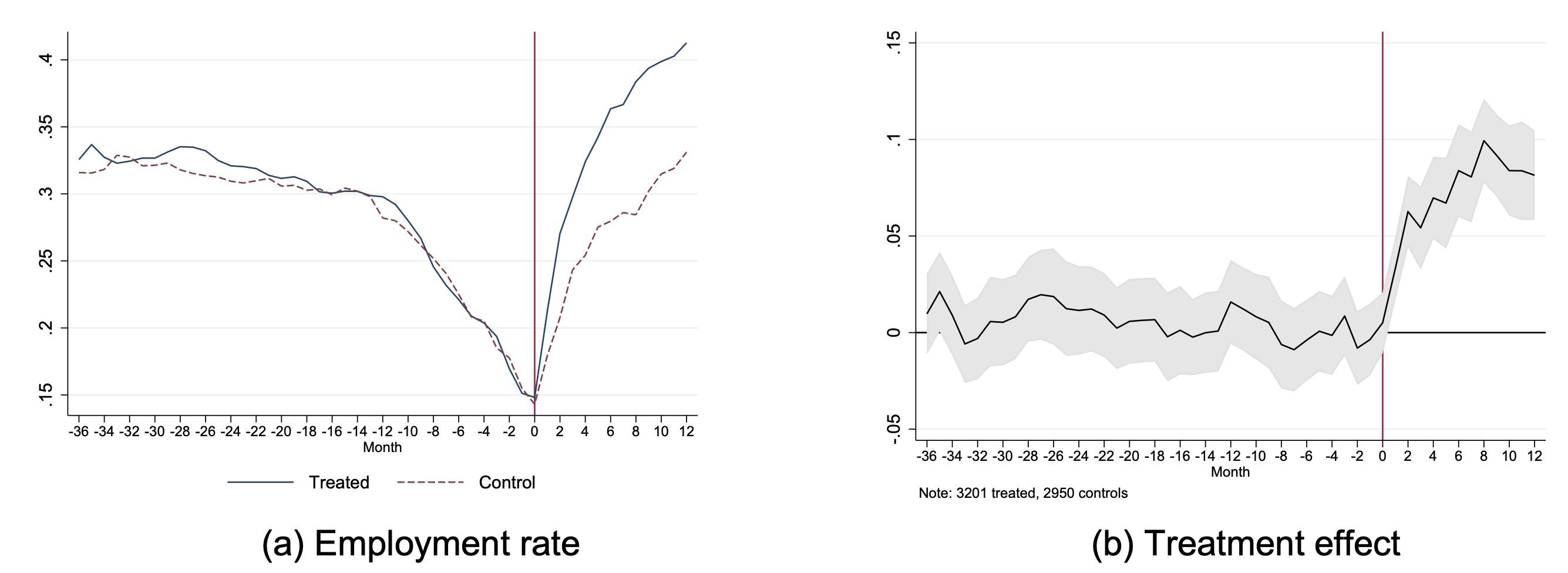

Figure 1 shows the programme’s impact on employment by estimating its effects on a monthly basis, from three years before random allocation to the programme to 12 months after that event. Figure 1a reports the share employed among the treatment and control groups and Figure 1b reports treatment versus control differences in employment along with confidence bands. The figure shows that the treatment and control groups had identical employment trajectories before randomisation. Their employment rate was about 32%, 36 months before randomisation. As is typical for populations enrolled in active labour market programmes, the employment rates of both groups show a decline (referred to as the ‘Ashenfelter dip’) that starts around 18 months before randomisation and accelerates during the year preceding randomisation. Twelve months after randomisation, the control group converges to the employment rate observed three years before randomisation (around 33%) while the treatment group surpasses its pre-programme employment rate at a record 41%. Overall, the programme increased employment rates by 24% relative to the mean of the control group.

Figure 1 Programme effects on employment

Notes: The figure reports employment rates for the treated and the control groups (left panel), and the difference in employment rates between the treated and control groups along with a 90% confidence interval (right panel) over time. Month zero corresponds to the month of random assignment.

At the same time, we find that the programme lessened participants’ income support dependency by 11 percentage points (a 26% decline). Our estimates further suggest that the decline in income support payments for the treatment group (relative to the control group) more than covered the costs of the programme within 12 months after allocation to treatment.

The effects of the programme were substantially larger among individuals with lower labour force attachment and a lower likelihood of employment, such as high-school dropouts and those with a longer history of income support dependency. In particular, the programme had a larger impact among individuals who were already claiming benefits at the time of allocation to the programme (the stock sample) relative to the new incoming flow of jobseekers.

Programme effects on soft skills

We survey treatment and control group participants 12 to 18 months after randomisation to assess their soft skills and self-perception. We measure:

(1) Self-esteem, which considers individuals’ sense of self-worth and personal value

(2) Work self-efficacy, which measures workers’ confidence in managing workplace situations such as respecting schedules and collaborating with colleagues is assessed

(3) Job-search self-efficacy, which refers to individual’s confidence in his/her ability to successfully search for a job and perform specific job-search tasks

(4) General self-efficacy, which assesses a person’s confidence in taking courses of action in a wide array of situations

(5) Grit, which refers to individual’s perseverance and passion to achieve long-term goals.

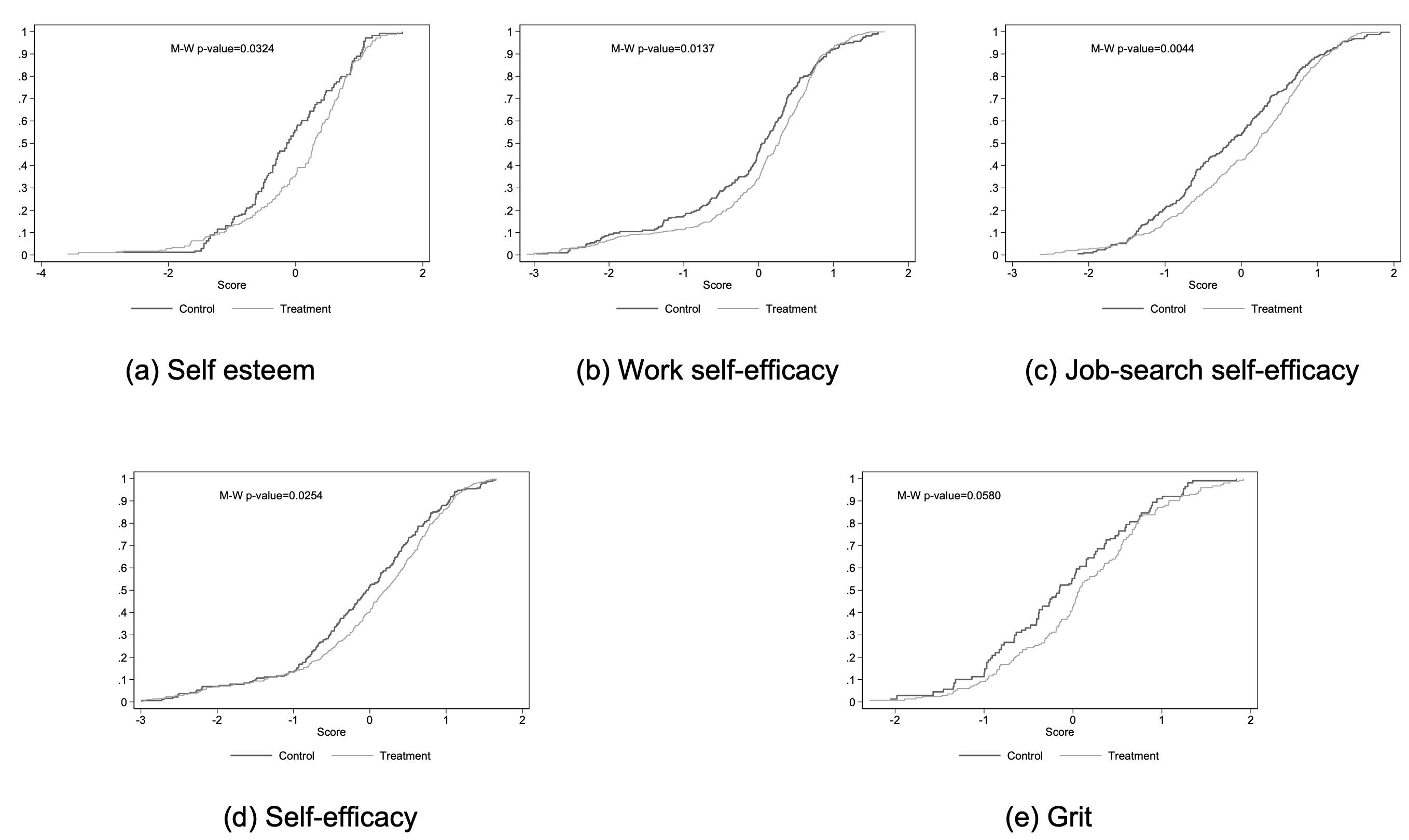

Figure 2 shows the cumulative distributions of these skills for the treatment and control groups. We present here the findings for the stock sample (i.e. individuals who were already claiming income support benefits at the time of randomisation). The distribution of soft skills of treated individuals dominates that of the controls across all dimensions of soft skills. We observe that the programme led to an increase in job-search self-efficacy, work self-efficacy, self-esteem, general self-efficacy, and grit. In our work, we also show that these soft skills are associated with superior labour-market outcomes and, as such, appear to mediate part of the impact of the programme on employment.

Figure 2 Programme effect on soft skills

Notes: The figures plot the cumulative distribution functions of soft skills for the sample of individuals who were already claiming income support benefits at the time of randomisation (the stock sample). Reported p-values refer to the results of the Mann-Whitney tests of stochastic dominance.

Long-term impacts and effects during the Covid-19 pandemic

We find that the impact of the programme is still evident in the long run, five to six years after its implementation. Individuals who were initially allocated to the treatment group were less likely to claim benefits relative to those allocated to the control group, five years after their participation in the programme. These differences even persisted during the Covid-19 pandemic where individuals in the treatment group were less likely to claim benefits relative to those allocated to the control group. Moreover, we find that conditional on claiming benefits, treated individuals appear more attached to the labour market as they were more likely to be unemployed (rather than on welfare) and if unemployed, they were more likely to be on furlough, relative to individuals in the control group.

Conclusion

Our results show that it is possible to enhance work-related attitudes and self-perception of long-term unemployed individuals in a cost-effective way, leading to an increase in their employment and earnings. Moreover, the benefits of such investment are still evident in the long term and even persisted during the Covid-19 pandemic, providing evidence on an effective intervention that helped disadvantaged groups to better cope with adverse labour market shocks.

References

Aghion, P, A Bergeaud, R Blundell and R Griffith (2020), “The innovation premium to soft skills in low-skilled occupations”, VoxEU.org, 2 January.

Barrera-Osorio F, A Kugler and M Silliman (2020), “Hard and soft skills in vocational training: Experimental evidence from Colombia”, VoxEU.org, 24 October.

Card D, J Kluve and A Weber (2018), “What works? A meta analysis of recent active labor market program evaluations”, Journal of the European Economic Association 16.3: 894-931.

Crépon, B, E Duflo, M Gurgand, R Rathelot and P Zamora (2013), “Do labor market policies have displacement effects? Evidence from a clustered randomized experiment”, The Quarterly Journal of Economics 128(2): 531-580.

Deming, D J (2017), “The Growing Importance of Social Skills in the Labor Market”, Quarterly Journal of Economics 132(4): 1593-1640.

Greenberg, D H, C Michalopoulos and P K Robins (2003), “A meta-analysis of government-sponsored training programs”, Industrial and Labor Relations Review 57(1): 31-53.

Levy Yeyati, E, M Montane and L Sartorio (2019), “Understanding what works for active labour market policies”, VoxEU.org, 3 September.

Heckman, J J, J Stixrud and S Urzua (2006), “The effects of cognitive and noncognitive abilities on labor market outcomes and social behavior”, Journal of Labor Economics 24(3): 411-482.

Kluve, J (2010), “The effectiveness of European active labor market programs”, Labour Economics 17(6): 904-918.

Schlosser, A and Y Shanan (2022), “Fostering Soft Skills in Active Labor Market Programs: Evidence from a Large-Scale RCT”, CEPR Discussion Paper No. 17055.