Sovereign wealth fund, a generic description of governmental investment activities, is a term that was coined just three years ago by Andrew Rozanov (2005). I identify sovereign wealth funds (SWFs) as separate pools of government-owned or government-controlled financial assets that include some international assets, which total at least $4 trillion by my latest count. Sovereign wealth funds take many forms and are designed to achieve a variety of economic and financial objectives – from stabilisation to intergenerational wealth transfer. They properly include government pension funds to the extent that they invest in marketable international assets. The very diversity of sovereign wealth funds may be one reason why they are poorly understood.

Myth 1: Sovereign wealth funds are about “them” not “us”

The media and many analysts would have one believe that sovereign wealth funds are entities established by non-Western, often non-democratic governments in pursuit of economic and political objectives that are orthogonal to those of traditional, market-oriented industrial countries. That may be a reasonable characterisation of a few funds but not of the vast majority. Industrial countries hold more than 40% of SWF international assets and about two-thirds of $8 trillion in total SWF assets. The United States leads with at least $800 billion in SWF international assets (second only to the United Arab Emirates). It is followed by Norway with more than $400 billion and the Netherlands and Japan with close to $300 billion. Tiny New Zealand’s Superannuation Fund holds about $8 billion.

A substantial proportion, but not all, of SWF assets of industrial countries are in government pension funds. Such funds may be legally distinguished from non-pension sovereign wealth funds, but as long as governments have some role in choosing their managements, at a minimum, they raise the same issues of motivation and accountability as do non-pension sovereign wealth funds regardless of their specific objectives, mandates, or sources of funding, which could be used as well to distinguish among non-pension sovereign wealth funds.

Myth 2: Sovereign wealth funds are all the same in their opacity

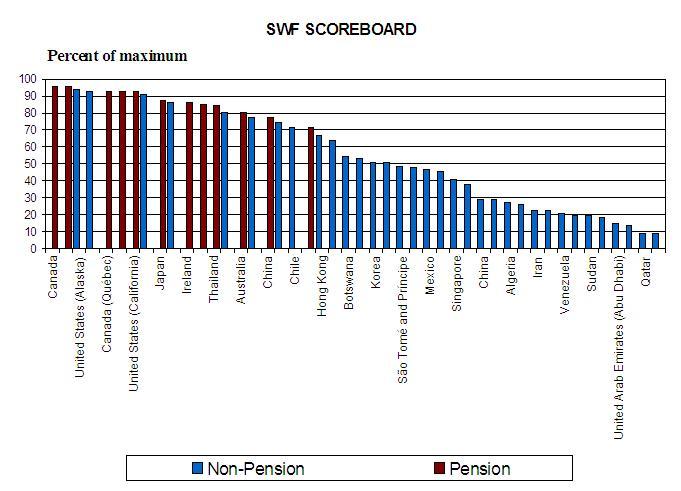

To many observers, a sovereign wealth fund is synonymous with a lack of transparency. For them, the current IMF-facilitated process to establish a set of generally accepted principles and practices for sovereign wealth funds should aim at increasing their transparency. In fact, the principles and practices primarily should aim at increasing SWF accountability, first, to the citizens of the countries that are the ultimate owners and presumptive beneficiaries of the funds and, second, to the citizens and politicians of countries in which they invest, as well as to all participants in financial markets. As I have established in my scoreboard for 46 pension and non-pension sovereign wealth funds of 38 countries, individual funds differ substantially in their current practices (Truman 2008a and 2008b).

What we observe in the SWF scoreboard is that no fund receives a perfect score. The scores of the funds range from a high of 95% on my 33-element scale to a low of 9%.1 The funds are not clustered at one end of the scale nor the other. Twenty-two funds have scores of more than 60%, including 12 representative pension funds, but there are also 10 non-pension funds. Fourteen funds have scores below 30%, including those of countries with some of the largest funds like the United Arab Emirates and China. (However, it is notable that China’s National Social Security Fund scores in the top group.) Ten funds fall in the middle group, including those of Singapore – Temasek Holdings and the Government of Singapore Investment Corporation – whose scores are both slightly below the average of 56% but whose actual practices differ significantly.

Figure 1 Sovereign wealth fund scoreboard

Thus, it is grossly misleading to generalise about the practices of sovereign wealth funds. At present, patters of practice differ substantially. Differences are understandable because they largely reflect decisions taken by governments in isolation before those governments discovered that their funds were part of a larger community of entities now described as sovereign wealth funds.

Myth 3: Sovereign wealth funds are a net benefit to the international financial system

One often reads statements that sovereign wealth funds provide unique benefits to the international financial system because, for example, they make needed capital injections into western financial institutions. No one should doubt that the recipients of those capital injections have benefited from them, and in time the citizens of the countries with the funds may benefit as well. However, sovereign wealth funds are not net providers of capital to western financial markets. For the most part, they are merely recyclers of global financial flows. In this respect, they do not differ from central banks and other government-controlled entities or from private sector investors. The only issues are where they invest, how wisely those investments are made, and how accountable the investors are for their decisions.

The financial resources that sovereign wealth funds have provided to foreign financial institutions for the large part were already parked in, or headed for, the financial markets of those institutions. The funds had either to disinvest from, or not invest in, other targets in order to help recapitalise the financial institutions. Citigroup’s gain was General Motor’s loss. The international financial system was going to receive those financial resources regardless.

Myth 4: Sovereign wealth funds are not like hedge funds

Another frequently heard refrain from supporters of sovereign wealth funds is that they are patient pools of capital with long-term horizons and are not like hedge or private-equity funds in their short-term speculative activities and use of leverage. Regardless of whether one thinks that patient capital is a net benefit to an economy or financial system, and most economists would argue that it is not, the facts do not support these intended favourable comparisons with hedge and private equity funds. Sovereign wealth funds invest extensively in those types of entities, as well as in other highly leveraged financial institutions such as commercial and investment banks whose activities, including the use of leverage, are indistinguishable today from those of the other two types of financial institutions. In effect, sovereign wealth funds provide the capital to be leveraged to generate the high rates of return.

Thus, those concerned about the accountability and transparency of highly leveraged, private sector institutions should be at least equally concerned about the accountability and transparency of sovereign wealth funds. Moreover, because sovereign wealth funds are owned and ultimately controlled by governments, it is naïve to believe that they can or should be treated as apolitical. The standards applied to sovereign wealth funds should be higher than those applied to private sector institutions precisely because they are governmental institutions that are not subject to the discipline of the market and ultimately are accountable to the citizens of their countries.

A framework of reciprocal responsibility

Having dismissed four myths about sovereign wealth funds, two on each side of the on-going debate, what should policymakers think and do about such funds? Policy makers should establish a framework of reciprocal responsibility for sovereign wealth funds.

Countries with the sovereign wealth funds should embrace a robust set of principles and practices to demystify the activities of their funds and to provide greater confidence to their own citizens that the huge amounts of financial resources involved will be deployed prudently according to the highest ethical and financial standards. Doing so implies setting aside national cultural norms and recognising that the stability of the international financial system requires that sovereignty stop at the water’s edge.

Countries receiving SWF investments should strengthen their openness to foreign investment from whatever source, subject to limited safeguards protecting national security narrowly defined. Moreover, countries receiving SWF investments should be careful what they wish for if they want their own sovereign wealth funds to receive national treatment in their international investments.

References

Rozanov, Andrew (2005), ‘Who Holds the Wealth of Nations,” Central Banking Journal, Vol. 15, no. 4.

Truman, Edwin M. (2008a), ‘A Blueprint for Sovereign Wealth Fund Best Practices,’ Peterson Institute for International Economics, Policy Brief 8-3.

Truman, Edwin M. (2008b), ‘The Rise of Sovereign Wealth Funds: Impacts on U.S. Foreign Policy and Economic Interests,’ Testimony before the Committee on Foreign Affairs, U.S. House of Representatives, May 21.

1 At least nine funds embrace, in whole or in part, each element of the scoreboard.