Markets and commentators are speculating that there may be a sustained pick-up in inflation in the US, after years of subdued price pressures. Along with continued solid US jobs growth and low unemployment, there are tentative signs of higher wage growth and the fiscal stimulus will also boost short-term growth. Global growth is also getting stronger (OECD 2018a).

As well as these recent developments, longer-term worldwide trends which have kept inflation generally low since the mid-1990s may also be reversing. In particular, globalisation appears to have stalled since the crisis, aggregate demand is strengthening, and output gaps have closed or are generally close to zero in most major countries. Moreover, there is mounting evidence of rising market power in services sectors. Together, these trends risk letting the inflation genie out of the bottle.

Declining inflation in many countries over the past few decades at the same time as rising global competition has led to a debate on the importance of globalisation for domestic inflation. Auer et al. (2017) at the BIS have argued that rising global value chain (GVC) integration has accentuated the importance of global factors – particularly global economic slack – for domestic inflation. However, recent research at the ECB (Tagliabracci et al. forthcoming) and at the US Federal Reserve (Yellen 2017) has disputed this conjecture.

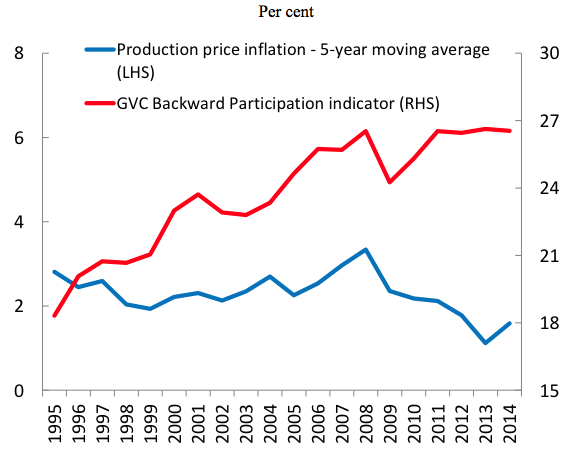

Figure 1 shows that GVC integration expanded significantly from 1995 until the crisis, while inflation remained relatively subdued. In the post-crisis period, GVCs flattened off and remained around the pre-crisis peak, while producer price inflation has fallen dramatically and remains very low on average across industries for our sample of countries.1

Figure 1 Global value chains and inflation (%)

Note: Unweighted averages across all country-industry cells where data are available. Backward participation in GVCs is the foreign value added share of a sector’s gross exports.

Source: Andrews et al. (2018) based on OECD STructural ANalysis (STAN) database; OECD Trade in Value-Added (TiVA) database; OECD TiVA Nowcast; and authors’ calculations.

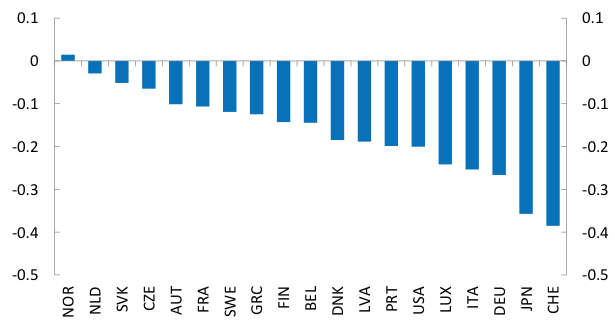

Motivated by this pattern, our new analysis of prices and globalisation (Andrews et al. 2018) goes beyond existing research by using recently released cross-country OECD data on prices and GVCs by industry, rather than at the country level, which allow us to control for time-varying country-specific and global shocks. We find that stronger backward GVC participation – that is, domestic producers relying more on foreign value-added content – is associated with lower producer price inflation at the industry level. For example, we estimate that the rise in GVCs from the mid-1990s up to the crisis reduced annual producer price inflation by 0.15 percentage points on average, but this effect is more than double in some OECD countries (Figure 2).

Figure 2 Impact of GVC expansion on inflation over 1996-2008

Estimated contribution of GVCs to average annual producer price inflation, percentage points

Note: The figure shows the annual change in producer price inflation based on the change in the production deflator that is explained by rising GVCs using the coefficient estimate in column 1 of Table 1. The estimates are the unweighted averages over industries in each country from 1996 to 2008. MEX, POL and SVN not shown as data on GVCs are not available for 1996.

Source: Andrews et al. (2018) based on calculations using estimation results and the OECD Trade in Value-Added (TiVA) database.

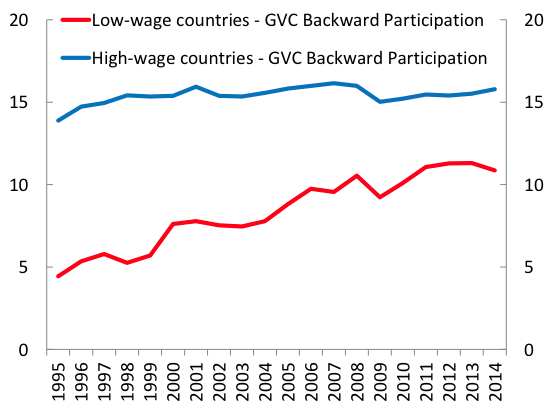

Confirming the existence of a cost-reduction and wage moderation channel, we also show that higher backward GVC participation is associated with lower wages and rising productivity in the importing countries and industries, especially when low-wage countries are integrated in their supply chains. This channel is likely to have contributed to lower inflation in recent years as the structure of the source (i.e. supplying) countries in GVCs has moved increasingly towards low-wage countries (Figure 3), despite a stall in the overall level of GVC integration (Figure 1). Therefore, inflation in advanced economies could remain low if the composition of GVCs continues to shift towards low-wage countries.

Figure 3 Countries with lower wages have been contributing more and more to GVCs

Backward GVC participation by source country groups (%)

Note: “High-wage countries” are those that are part of the EU-15 (EU members prior to 2004) plus Australia, Canada, Japan, New Zealand, Norway, Switzerland and the United States; “Low-wage countries” are all other countries in the TiVA database. Unweighted average across all country-industry cells where data are available. Backward participation in GVCs is the foreign value added share of a sector’s gross exports.

Source: Andrews et al. (2018) based on OECD Trade in Value-Added (TiVA) database; OECD TiVA Nowcast; and authors’ calculations.

Moreover, we find that a high levelof GVC integration can also dampen producer price inflation by accentuating the impact of global economic slack on domestic inflation. This provides new industry-level evidence to support the finding of Auer et al. (2017), who use aggregate data covering the pre-crisis period. We show this by using a similar approach combining bilateral industry-level GVC and national output gap data to measure changes in global slack over time.

This implies that weak global demand has a larger disinflationary impact when GVC participation is higher. For example, given our sample of countries facing an average global output gap of -1.5% in 2014, we estimate that annual producer price inflation was on average 0.25 percentage points lower in 2014 than for 1996 GVC levels. This figure is more than 0.5 percentage points, however, for countries that experienced a particularly large rise in GVC participation. But with slowing expansion of GVCs since the crisis, coupled with stronger aggregate demand and output gaps closing in most countries, this could lead to greater inflationary pressures in the medium term.

The third longer-term trend posing an upside risk to inflation is declining competition and market contestability. We exploit harmonised cross-country firm-level data to show an increasing trend in mark-ups, which suggests rising market power in services sectors (Figure 4).This upward trend in mark-ups is consistent with other estimates for the US (De Loecker and Eeckhout 2017) and other OECD countries (Calligaris et al. 2018). In turn, in these market services sectors we find a significant positive correlation between producer price inflation and mark-ups within industries since the early 2000s. This leads us to conjecture that if market power continues to rise, it may pose a further risk to letting the inflation genie out of the bottle.

Figure 4 Mark-ups are on the rise in services

Estimated firm-level mark-ups averaged across broad sectors and countries, percentage points

A. Services

B. Manufacturing

Note: The figure shows the 3-year moving average of size-weighted mark-ups aggregate to the 2-digit sector for each country and year, and then averaged across them by two sector-groups, manufacturing and non-financial business services.

Source: Andrews et al. (2018) based on calculations using the Orbis database of Bureau van Dijk.

This analysis suggests that the expansion of GVCs facilitated by trade liberalisation and advances in technology has put downward pressure on producer prices, with potential implications for monetary policy. Looking forward, a continuation of the stalling globalisation observed since the crisis poses an upside risk to future inflation. This provides a further reason to resist the rising threat of trade protectionism in the global economy.

In addition, if more intense competition in product and labour markets contributed to global disinflation in over recent decades (Rogoff 2003), then it follows that waning structural reform ambition (OECD 2018b) – against the backdrop of strengthening global growth – could lead to inflationary pressures. Given the growing importance of ICT-based activities in the economy, as well as evidence of increasing market power in those industries, policy efforts to adapt anti-trust and pro-competitive market regulations to the digital age will not only bring benefits to long-run productivity growth, but will also be desirable from a monetary policy perspective.

References

Andrews, D, P Gal and W Witheridge (2018), “A Genie in a Bottle? Globalisation, Competition and Inflation”, OECD Economics Department Working Papers, No. 1462.

Auer, R, C Borio and A Filardo (2017), “The globalisation of inflation: The growing importance of global value chains”, BIS Working Papers, No. 602, January.

Calligaris, S, C Criscuolo and . Marcolini (2018), “Digital and market transformations”, OECD Science, technology and industry working papers, forthcoming.

De Loecker, J and J Eeckhout (2017), "The Rise of Market Power and the Macroeconomic Implications", NBER Working Papers 23687.

OECD (2018a), Interim Economic Outlook, March 2018.

OECD (2018b), Economic Policy Reforms: Going for Growth 2018, March.

Rogoff, K (2003), “Globalization and global disinflation”, Paper presented at the Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas 2003 Jackson Hole Conference.

Tagliabracci, A, C. Osbat and G Koester (forthcoming), “The role of foreign slack and global integration for domestic inflation”.

Yellen, J (2017), “Inflation, Uncertainty, and Monetary Policy”, Speech at the “Prospects for Growth: Reassessing the Fundamentals” 59th Annual Meeting of the National Association for Business Economics, September 26.

Endnotes

[1] The sample of countries are: Austria, Belgium, Czech Republic, Denmark, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Italy, Japan, Luxembourg, Latvia, Mexico, Netherlands, Norway, Poland, Portugal, Slovenia, Slovak Republic, Sweden, Switzerland and the United States.