While social scientists can run experiments to learn about the effects of a broad range of treatments, it is impossible to randomise political systems. Yet, understanding the effects of communism, democracy, and autocracy on people’s lives is of great importance. Not surprisingly, there is a wide literature exploring how political systems persistently affect the economy and population preferences, with a particular focus on different legacies between capitalist and socialist societies (for a review, see Simpser et al. 2018).

Studying persistent East–West differences after German division and reunification

German division and reunification has attracted the interest of many social scientists as it seems quite close to an experimental setting. After WWII, two previously united parts of the same country were assigned to two opposing political regimes, a capitalist West and a communist East. Reunification in 1990 brought the two parts under the same political system once again.

In terms of overall economic outcomes, income per capita did not differ widely between East and West Germany before WWII (see Alesina and Fuchs-Schündeln 2007). But by the time East Germany collapsed, East German GDP per capita was less than half of that of West Germany. After reunification, labour productivity in East Germany was at a third of the Western level, putting the East somewhere between Mexico and Chile. The communist system had ended in economic failure.

Given salient differences between the political and economic systems of West and East Germany, a large literature has argued that the communist experience had enduring effects on the population in the East, including their economic outcomes, political attitudes, cultural traits, and gender roles (e.g. Alesina and Fuchs-Schündeln 2007, Campa and Serafinelli 2019, Laudenbach et al. 2019, Goldfayn-Frank and Wohlfart 2020, Lippmann et al. 2020).

In a recent paper (Becker et al., forthcoming), we take a fresh look at the German case. Were East and West indeed similar before World War II? Did the war and the subsequent occupation affect the two parts of the country in the same way? What about migration between East and West from 1945 until the building of the Berlin Wall in 1961? And what does all this imply for our understanding of the effects of communism?

East Germany can be spotted before it even existed

The location of the border between the German Democratic Republic (GDR) and the Federal Republic of Germany (FRG) is not the random outcome of where American, British, and Soviet tanks stopped at the end of WWII in 1945. Instead, in anticipation of the defeat of Nazi Germany, the three allied forces had agreed in 1944 on a division of post-WWII Germany into Soviet and Western occupation zones that followed the pre-WWII borders of the German Empire states and the provinces of the largest state, Prussia (with a few very minor exceptions for geographic connectedness). As a result, the East–West border separated the populations of pre-existing regions with distinct histories and cultures.

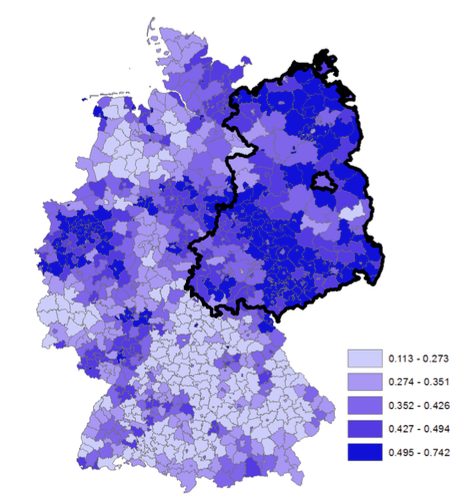

Since the border follows pre-existing regions, we can explore pre-WWII county-level data to investigate whether West and East differed in relevant dimensions. A first dimension is the size of the working class, strongly emphasised by communist countries. Inspecting pre-WWII data, we see that the East Germany already had a substantially higher working-class share in 1925 (Figure 1), well before the area became communist. The difference between East and West in working-class share amounts to 12 percentage points. In fact, the working-class share jumps quite abruptly in several regions around the later inner-German border: it is significantly detectable when focusing on counties within 100 kilometres of the later border or on the counties that have a direct contact with the later border.

Figure 1 The working-class share in 1925: East–West differences before the GDR existed

Source: Becker et al., forthcoming.

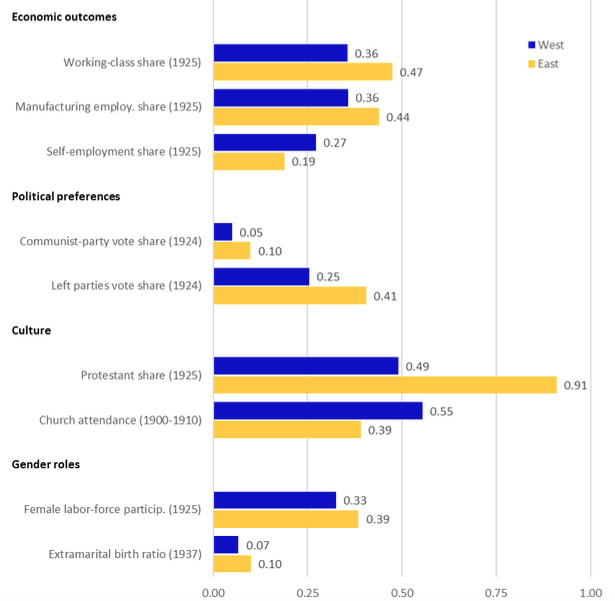

East–West differences before WWII are salient in other dimensions as well. Figure 2 shows comparisons in economic outcomes relevant to the onset of communism. Among others, the manufacturing-employment share was significantly higher in the East, whereas the East’s share of the population that is self-employed was significantly lower (Fritsch and Wyrwich 2014).

Figure 2 East–West differences before WWII

Source: Own depiction based on Becker et al., forthcoming.

Interestingly, political preferences also already differed before WWII. The communist vote share in the East was double that of the West in 1924. When looking at left-wing parties more broadly (in particular, adding Social Democrats), the left vote share was 15 percentage points higher in the East.

Communism is often thought to have crowded out religion. But East Germany already had lower church attendance (in the Protestant church) at the beginning of the 20th century (Hölscher 2001). Furthermore, while the West was roughly balanced between Protestants and Catholics, the East was predominantly (91%) Protestant (Becker and Woessmann 2009).

Finally, the socialist GDR put much emphasis on getting women to work. Yet, already before WWII, female labour-force participation was higher in the East (Wyrwich 2019). In addition, East and West differed markedly in the incidence of extramarital births before WWII (Klüsener and Goldstein 2016).

To the extent that some of these pre-existing differences persisted through the communist period, they may well be an essential source of post-reunification heterogeneity between East and West Germans.

WWII and occupying forces affected East and West differentially

East and West were differentially affected by WWII and the occupying forces. Using data from the German Census jointly administered in all four occupation zones in October 1946, we show that the ratio of men to women was substantially lower in the Soviet zone. No such differences had existed in the last pre-WWII census, in 1939.

The larger decrease in the sex ratio in the Soviet zone may reflect a larger war-related male death toll, but potentially also mirrors sex imbalances in very early East–West migration. Whatever the source, the difference may have contributed to differences in several outcomes, such as female labour-force participation, gender roles, and even political views.

The East also suffered larger losses due to the dismantling of capital equipment by and paying reparations to the occupying forces during 1945–1949. This gave the GDR a worse starting position than the FDR (Sleifer 2006).

A selective fifth of the population left the East before building of Berlin Wall

The four occupation zones were established in 1945, and the GDR was founded in 1949. But it was possible, albeit increasingly difficult, to migrate between the two parts of Germany until the Berlin Wall was built in 1961. In fact, about one in five of East Germany’s population migrated West until 1961. While there is no data to compare these emigrants to those who stayed behind in the East, we show that individuals who moved from East to West differed from local West Germans in being more likely to be white-collar workers, self-employed, and better educated. Presumably, they were also less receptive to the communist doctrine (see also Bauernschuster et al. 2012).

What is sometimes overlooked is that also about half a million people migrated from the West to the East before 1961. GDR propaganda describes them as “not in agreement with the capitalist system”. We show that six of the 19 Politburo members in the early GDR (1949–1961) had been born in what became West Germany, including long-time GDR leader Erich Honecker. Taken together, the evidence suggests that there was selective migration and sorting by political preferences.

Caution warranted when interpreting evidence on ‘effects’ of communism

Considering these findings of pre-existing East–West differences, differential effects of WWII and the subsequent occupation, and selective East–West migration, is the German setting still useful to study the impact of communism? We think that the answer is yes, as it does offer some unique advantages.

However, we emphasise that each research question requires sensible consideration of the outlined challenges. The most convincing evidence of the effect of political systems probably stems from the post-reunification convergence of some economic behaviours, political preferences, and trust in the state. The experience of having lived in the communist system also seems to have permanently altered consumption patterns. In addition, the communist system likely shaped gender roles in terms of female labour-force participation or fertility preferences, but these also include a strong legacy component already visible before WWII.

The more general insight is that the development of political systems is hardly ever exogenous. For example, political systems become endogenous if political preferences are endogenous to prior experiences (Fuchs-Schündeln and Schündeln 2015). This idea is most apparent in revolutions started by groups frustrated with the current system. But effects of political systems must be carefully assessed even if a new political system is imposed by external players: regime changes may consider pre-existing conditions, and people dissatisfied with the new regime may simply choose to ‘vote with their feet’ and emigrate, leaving behind a population reasonably well aligned with the new regime.

References

Alesina, A, and N Fuchs-Schündeln (2007), “Goodbye Lenin (or not?): The effect of communism on people”, American Economic Review 97 (4): 1507–28.

Bauernschuster, S, O Falck, R Gold and S Heblich (2012), “The shadows of the socialist past: Lack of self-reliance hinders entrepreneurship”, European Journal of Political Economy 28(4): 485–97.

Becker, S O, L Mergele and L Woessmann (2020), “The separation and reunification of Germany: Rethinking a natural experiment interpretation of the enduring effects of communism”, Journal of Economic Perspectives 34(2), forthcoming.

Becker, S O, and L Woessmann (2009), “Was Weber wrong? A human capital theory of Protestant economic history”, Quarterly Journal of Economics 124(2): 531–96.

Campa, P, and M Serafinelli (2019), “Politico-economic regimes and attitudes: Female workers under state socialism”, Review of Economics and Statistics 101(2): 233–48.

Fritsch, M, and M Wyrwich (2014), “The long persistence of regional levels of entrepreneurship: Germany, 1925–2005”, Regional Studies 48(6): 955–73.

Fuchs-Schündeln, N, and M Schündeln (2015), “On the endogeneity of political preferences: Evidence from individual experience with democracy”, Science 347(6226): 1145–8.

Goldfayn-Frank, O, and J Wohlfart (2020), “Expectation formation in a new environment: Evidence from the German reunification”, Journal of Monetary Economics, forthcoming.

Hölscher, L (2001), Datenatlas zur religiösen Geographie im protestantischen Deutschland: Von der Mitte des 19. Jahrhunderts bis zum Zweiten Weltkrieg, 4 vols., Berlin: Walter de Gruyter.

Klüsener, S, and J R Goldstein (2016), “A long-standing demographic East–West divide in Germany”, Population, Space and Place 22(1): 5–22.

Laudenbach, C, U Malmendier and A Niessen-Ruenzi (2019), “The long-lasting effects of experiencing communism on attitudes towards financial markets”, working paper.

Lippmann, Q, A Georgieff and C Senik (2020), “Undoing gender with institutions: Lessons from the German division and reunification”, Economic Journal, forthcoming.

Simpser, A, D Slater and J Wittenberg (2018), “Dead but not gone: Contemporary legacies of communism, imperialism, and authoritarianism”, Annual Review of Political Science 21(1): 419–39.

Sleifer, J (2006), “Planning ahead and falling behind: The East German economy in comparison with West Germany 1936–2002”, in Jahrbuch für Wirtschaftsgeschichte, Beiheft 8, Berlin: Akademie Verlag.

Wyrwich, M (2019), “Historical and current spatial differences in female labour force participation: Evidence from Germany”, Papers in Regional Science 98(1): 211–39.