Reducing tax evasion is a key concern of governments around the world, as tax evasion leads to billions of euros in losses of public revenue. Tax evasion also creates economic distortions and efficiency losses (e.g. Feldstein 1999, Chetty 2009) and forces countries to rely on inefficient tax instruments (e.g. Gordon and Li 2009, Best et al. 2016). This is particularly the case in developing countries, where tax enforcement capacity is often more limited (Besley and Persson 2013).

One pernicious form of tax evasion involves so-called ghost firms – fake firms that are set up to help other companies evade taxes. These firms – sometimes also known as ‘invoice mills’ or ‘missing traders’ – issue fake receipts, pretending that they sold something to a client firm when no real transaction took place. This allows the client firm to take a tax deduction for fake input costs from their corporate income and value added taxes. At the same time, the ghost firm does not pay taxes on the revenue stated on its receipts.

In recent work (Carrillo et al. 2022), we use transaction-level tax data from Ecuador to provide a unique window into both the patterns of the ghost economy and an innovative enforcement strategy. We find that evasion through the use of ghost deductions is widespread and quantitatively important. Ghost clients are not limited to small, semi-formal firms. On the contrary, larger firms are more likely to engage in ghost transactions and feature larger shares of such transactions in total input costs. Tax evasion via ghost firms benefits those at the top of the income distribution. It has a regressive effect in that ghost deductions are disproportionately used by firms owned by high-income individuals. We also find that receipts from ghost firms exhibit suspicious patterns compared to ordinary transactions: bunching at round numbers, at the end of the fiscal year, and just below financial-system thresholds.

We then analyse the impact of a creative enforcement policy against the use of ghost firms. Issuing falsified invoices is commonly regarded as a criminal activity that is severer than other types of evasion such as simple revenue under-reporting (de La Feria 2020, OECD 2021), but enforcement efforts directly targeting ghost firms face unique obstacles. Ghosts are often part of criminal enterprises; ‘owners’ may be shell companies, deceased individuals, or victims of identity theft; and ghosts are often transient, disappearing and re-emerging as new entities (OECD 2006, de La Feria 2020). This turns enforcement efforts into a game of whack-a-mole. To deal with these challenges, in 2016 the Ecuadorian Internal Revenue Service began to target ghost client firms rather than chasing the ghosts themselves. Since the client firms are typically large, established companies that cannot simply disappear, this approach proved highly effective.

Our analysis is based on a list of over 800 ghost firms that the Internal Revenue Service identified in 2016. The tax authority identified potential ghost firms based on information from audits, whistle-blowers, and tax records. Next, Internal Revenue Service attempted to contact candidate ghost firms. Firms that were neither found at their registered address nor responsive to emails were considered likely ghost firms and published as such on the Internal Revenue Service website. Firms were encouraged to inform the Internal Revenue Service if they were erroneously listed as likely ghost firms and could prove their real existence. In the rare cases that this happened, firms were removed from the list. As we show below, the highly suspicious pattern of transactions with these firms is consistent with Internal Revenue Service’s conclusion that they are ghost firms.

Characteristics of ghost client firms and their owners in Ecuador

Fact 1: Tax deductions based on fake receipts from ghost firms are widespread and large. Between 2010 and 2015, 10% of unique firms in Ecuador claimed deductions based on receipts from at least one identified ghost firm (likely a subset of true ghosts). Among those clients, ghost deductions represent on average 10.4% of the value of their purchase deductions. In total, ghost clients reported ghost transactions amounting to $2.1 billion in value over 2010–2015.

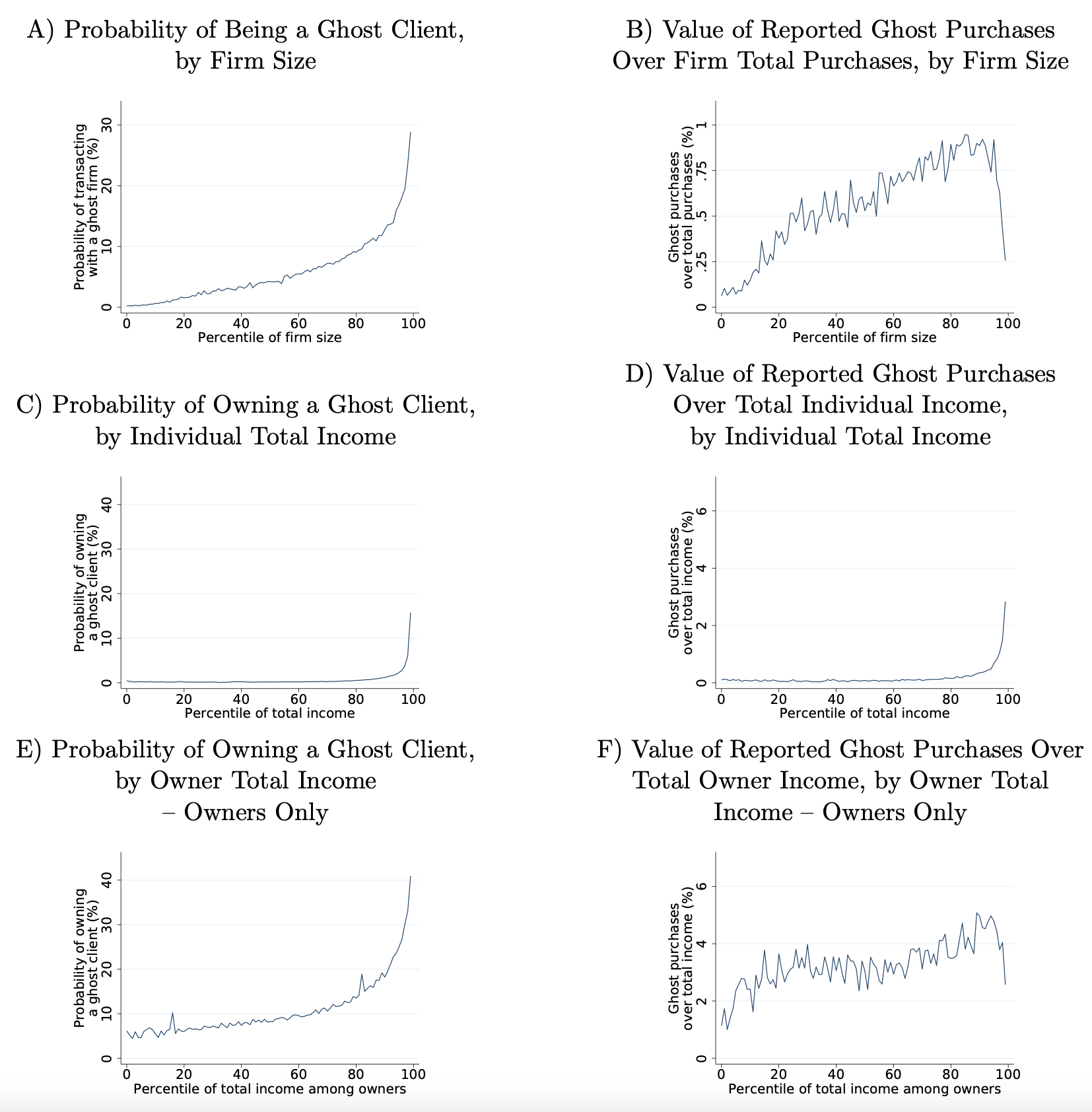

Fact 2: Evasion through ghost firms is more prevalent among relatively large firms. Ghost clients are much bigger than other firms, with higher revenues, costs, and tax liabilities. Indeed, the probability of engaging in ghost transactions increases monotonically in firm size (Figure 1, Panel A). While this could be driven by larger firms simply having more transactions, the share of ghost deductions out of total deductions also increases throughout most of the size distribution (Panel B).

Fact 3: Ghost deductions are used especially by firms owned by high-income individuals. We find that the probability of having ownership of a ghost client is highly concentrated at the top of the income distribution (Panel C). Moreover, ghost purchases attributed to firm owners are also increasing in the individual’s income (Panel D) – we attribute firms’ ghost purchases to individuals by multiplying ghost purchases with ownership shares. These patterns also hold for the distribution of firm owners (Panels E and F).

Figure 1 Distributional implications of ghost transactions

Notes: Descriptive results on the use of receipts from ghost firms across the distribution of client firms’ size and individuals’ incomes (pooled 2010–2015). Outcome variables trimmed at the top 1%. For details, see Figure 1 in Carrillo et al. (2022).

Patterns of reported transactions with ghost firms in Ecuador

Next, we analyse the patterns of transactions of ghost clients with ghost firms, compared to the transactions of these same client firms with non-ghost firms.

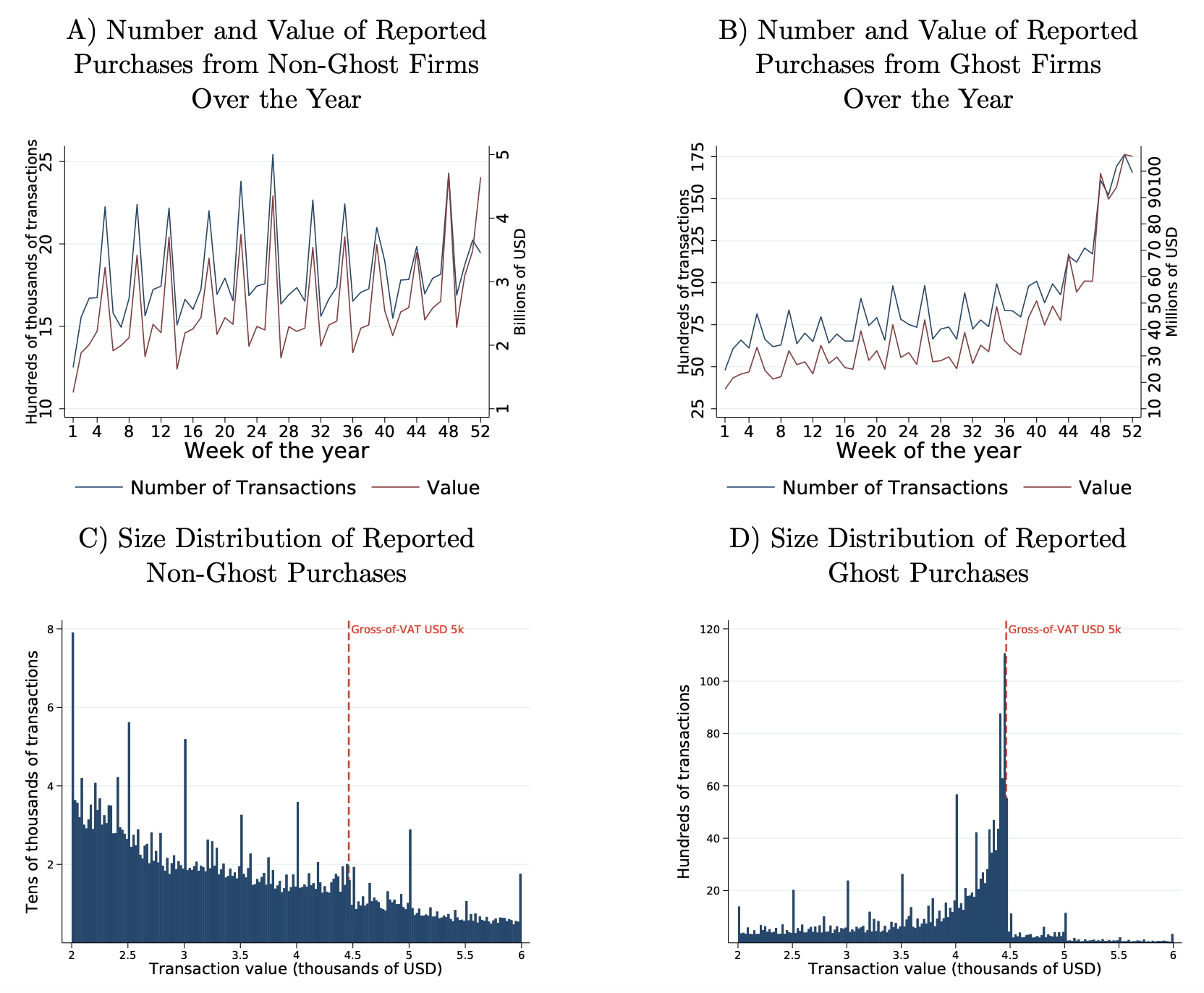

Fact 4: Ghost transactions are clustered towards the end of the tax year. While regular transactions oscillate relatively steadily throughout Ecuador’s tax year (which is also the calendar year), ghost transactions increase strongly toward the end of the year in both number and value (Figure 2, Panels A and B). This is consistent with firms assessing their annual revenues at the end of the year and then utilising ghost transactions to achieve a target reported-profit level or rate for tax purposes.

Fact 5: Ghost transactions exhibit suspicious round-number bunching compared to regular transactions. In particular, 6.5% of net-of-VAT values for ghost transactions are multiples of $500, far more than for purchases from regular firms (0.7%).

Fact 6: Ghost transactions systematically avoid payments through the financial sector. In particular, reported transaction values with ghost firms bunch below the threshold above which firm-to-firm payments must be made through the formal financial sector (Figure 2, Panel D). By contrast, there is little bunching in transactions with regular firms around this cut-off (Panel C). Such thresholds are common in many countries. In Ecuador, this threshold corresponds to $5,000 (gross of VAT) during our study period.

Figure 2 Impact of the enforcement campaign on tax liabilities (in US dollars)

Notes: Panels A and B show the weekly number and total value of reported purchases over the year, and Panels C and D the frequency of values for reported purchases from non-ghost firms and ghost firms respectively, among economically active ghost clients that file a purchase annex (pooled 2010–2015). Transaction values are net of VAT. For ease of visibility, Panels C and D include only transactions that are fully subject to VAT. For details, see Figure 2 in Carrillo et al. (2022).

Tax enforcement against the use of ghost receipts

The Ecuadorian Internal Revenue Service began an innovative enforcement scheme in 2016 to combat the use of ghost receipts and to recoup tax revenues lost due to ghost deductions. To overcome the whack-a-mole problem of chasing ghost firms, the authority then targeted the ghost clients rather than the ghosts themselves. Notifications were sent to over 1,500 client firms, informing them about the detected ghost transactions on previously filed tax returns and requesting that they submit revised returns removing those deductions.

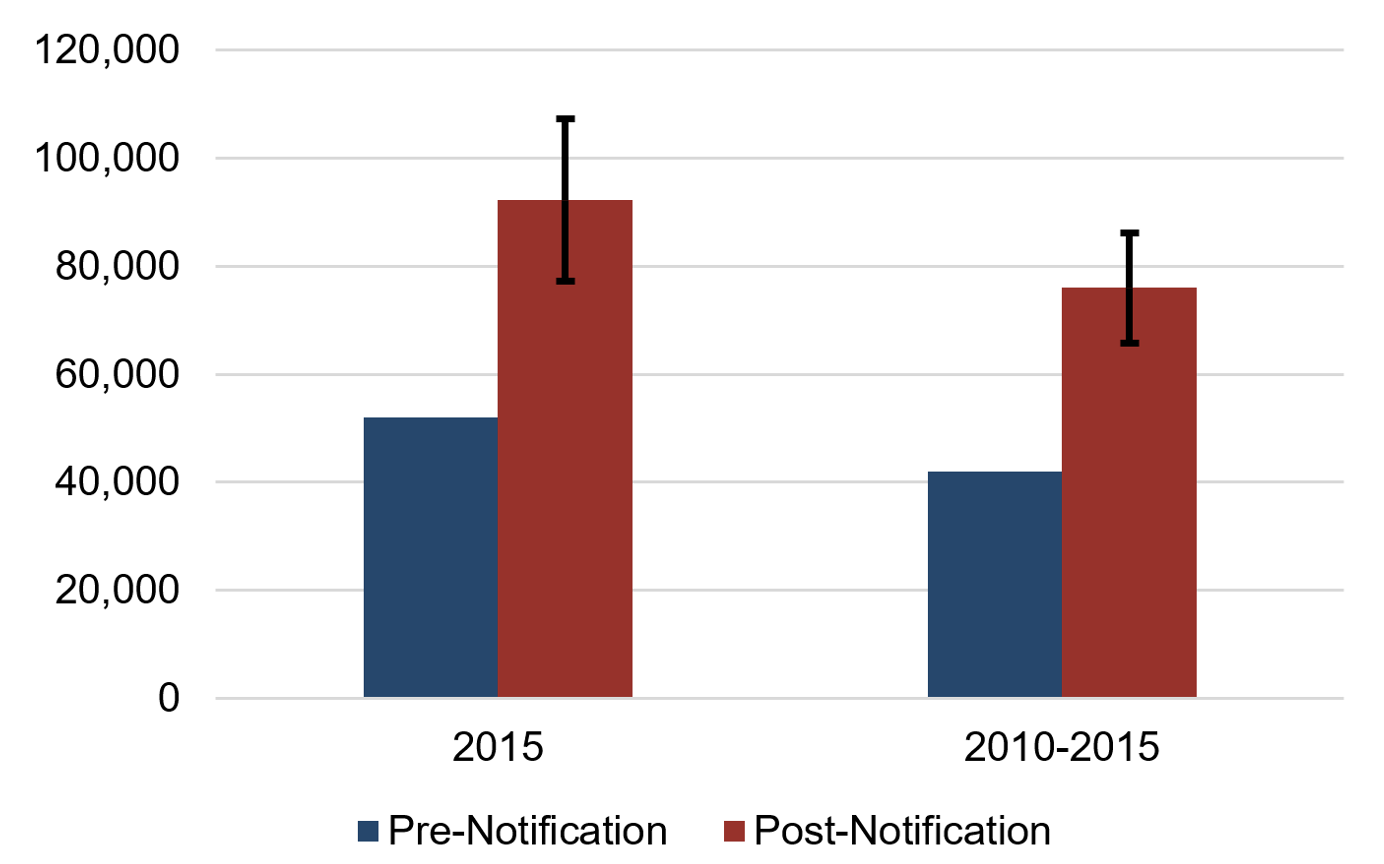

The policy was highly effective and resulted in a total increase in reported firm income tax of $20.6 million within three months. About one in four notified firms made an amendment, reducing previously filed non-labour cost deductions, within 90 days of receiving a notification. Tax liability increased by $40,000 per notification concerning the tax year 2015 and by $34,000 for notifications concerning the full study period 2010–2015 (Figure 3). This represents an increase of 81% of the original filing of amending firms.

Figure 3 Impact of the enforcement campaign on tax liabilities (in US dollars)

Notes: Mean reported tax liability before and after amendments, among firms that made an amendment reducing previously filed non-labour cost deductions, within 90 days of receiving a notification. The first set of bars refers to filings concerning the tax year 2015; the second set of bars is pooled for 2010–2015. The vertical line displays the 95% confidence interval of treatment effect estimates. For details, see Table 2 in Carrillo et al. (2022).

Importantly, firms do not appear to offset the tax liability increase by reporting significantly lower revenues in their tax amendment. This finding is interesting in the context of previous studies that analysed enforcement campaigns targeting under-reported revenues. While such campaigns have been shown to increase reported revenue, firms have also been found to offset increases in their tax liability by increasing reported costs at the same time (Asatryan and Peichl 2017, Carrillo et al. 2017, Slemrod et al. 2017, Almunia and Lopez-Rodriguez 2018, Mascagni et al. 2018, Naritomi 2019, Li and Wang 2020).

Finally, the tax increases resulting from this intervention are even more strongly concentrated among firms owned by high-income individuals than the overall use of ghost deductions. For example, the amount of additional tax reported as a share of owners’ income is 170 times higher in the top 1% than in the bottom 80% of the income distribution. This shows that curbing the tax evasion facilitated by ghost firms can have progressive distributional implications.

Implications

Overall, these results illustrate that ghost firms can play an important role in hampering governments’ goal of strengthening tax capacity and increasing horizontal and vertical equity in taxation. Since low- and middle-income countries rely disproportionally on tax revenues collected from firms, this form of organised evasion can make a big dent in their revenue collection. The approach of targeting ghost clients, rather than the elusive ghost themselves, shows promise for policymakers dealing with this challenging phenomenon.

Editors’ note: A version of this column first appeared on VoxDev.

References

Almunia, M, and D Lopez-Rodriguez (2018), “Under the radar: The effects of monitoring firms on tax compliance”, American Economic Journal: Economic Policy 10(1): 1–38.

Asatryan, Z, and A Peichl (2017), “Responses of firms to tax, administrative and accounting rules: Evidence from Armenia”, CESifo Working Paper No. 6754.

Besley, T, and T Persson (2013), “Taxation and development”, Handbook of Public Economics 5: 51–110.

Best, M C, A Brockmeyer, H J Kleven, J Spinnewijn and M Waseem (2016), “Designing tax policy in high-evasion economies”, VoxEU.org, 5 January.

Carrillo, P, D Donaldson, D Pomeranz and M Singhal (2022), “Ghosting the tax authority: Fake firms and tax fraud”, CEPR Discussion Paper No. 17453.

Carrillo, P, D Pomeranz and M Singhal (2017), “Dodging the taxman: Firm misreporting and limits to tax enforcement”, American Economic Journal: Applied Economics 9(2): 144–64.

Chetty, R (2009), “Is the taxable income elasticity sufficient to calculate deadweight loss? The implications of evasion and avoidance”, American Economic Journal: Economic Policy 1(2): 31–52.

de La Feria, R (2020) “Tax fraud and selective law enforcement”, Journal of Law and Society 47(2): 240–70.

Feldstein, M (1999), “Tax avoidance and the deadweight loss of the income tax”, Review of Economics and Statistics 81(4): 674–80.

Gordon, R, and Li, W (2009), “Tax structures in developing countries: Many puzzles and a possible explanation”, Journal of Public Economics 93(7–8): 855–66.

Li, J, and X Wang (2020), “Does VAT have higher tax compliance than a turnover tax? Evidence from China”, International Tax and Public Finance 27(2): 280–311.

Mascagni, G, A Mengistu and F B Boldeyes (2018), “Can ICTs increase tax? Experimental evidence from Ethiopia”, International Centre for Tax and Development.

Mittal, S, O Reich and A Mahajan (2018), “Who is bogus? Using one-sided labels to identify fraudulent firms from tax returns”, Proceedings of the 1st ACM SIGCAS Conference on Computing and Sustainable Societies (1-11).

Naritomi, J (2019), “Consumers as tax auditors”, American Economic Review 109(9): 3031–72.

OECD (2006), “Report on identity fraud: Tax evasion and money laundering vulnerabilities”, OECD Centre for Tax Policy and Administration.

OECD (2021), Fighting tax crime - The ten global principles, second edition, Paris: OECD Publishing.

Slemrod, J, B Collins, J L Hoopes, D Reck and M Sebastiani (2017), “Does credit-card information reporting improve small-business tax compliance?”, Journal of Public Economics 149: 1–19.

Slemrod, J, and T Velayudhan (2022), “The VAT at 100: A retrospective survey and agenda for future research”, Public Finance Review 50(1): 4–32.

Waseem, M (2020), “Overclaimed refunds, undeclared sales, and invoice mills: Nature and extent of noncompliance in a value-added tax”, CESifo Working Paper No. 8231.