At the beginning of the 20th century, men dominated high-skilled professions and, even today, women remain under-represented in most high-skilled professions, especially in senior positions. For instance, only 5.8% of CEO positions in Fortune 500 firms were held by women (Bertrand et al. 2019) and only 9.5% of patents were filed by women in OECD countries (OECD 2021).

In academia, women remain under-represented across most disciplines and countries. The persistent under-representation of women is a growing concern for researchers, policymakers, and the general public (e.g. Beidas et al. 2022, Romanowicz 2019). In recent years, a growing literature has analysed gender gaps in academia, investigating publications, citations, or promotions and focusing on specific disciplines, countries, and limited periods (e.g. Bagues et al. 2017, Card et al. 2020, 2022, Sarsons 2017, Sarsons et al. 2021, Koffi 2021, Ross et al. 2022).

Although progress has been made in understanding gender gaps in academia, there is still much to be explored. In particular, little is known about the long-run evolution of gender gaps in academia across countries and disciplines. In addition, it is unclear which domains such as hiring, publishing, citations, or promotions exhibit the most pronounced gender gaps and whether these gaps interact across domains.

In a recent study (Iaria et al. 2022), we trace the evolution of gender gaps in academia across multiple domains over the 20th century and across the globe. The study analyses the largest database of university academics ever assembled.

We collected data from historical records and modern university websites, resulting in roughly 500,000 observations covering academics from over 7,000 universities in more than 130 countries, encompassing all disciplines, for six cross-sections (cohorts) spanning from 1900 to 1969. We augmented these data with information on academics in three academic disciplines for the year 2000, covering prestigious universities for which we have information throughout the 20th century.

The unique quality of the data derives from manual enhancements that enrich the faculty rosters, including coding the gender of academics, following academic careers by linking academics over time, manually recoding specialisations into disciplines, and linking academics to publication and citation databases.

Because the data are based on complete faculty rosters rather than publication databases, we can study the entire population of academics, including those who may not have published or not have been cited. This allows us to overcome important selection biases and present a more accurate picture of the role of women in academia, which is not restricted to the sample of publishing academics. In this recent study, we investigate gender gaps in four domains: hiring, publications, citations, and promotions. We also investigate how gender gaps interact across domains.

Gender gaps in hiring

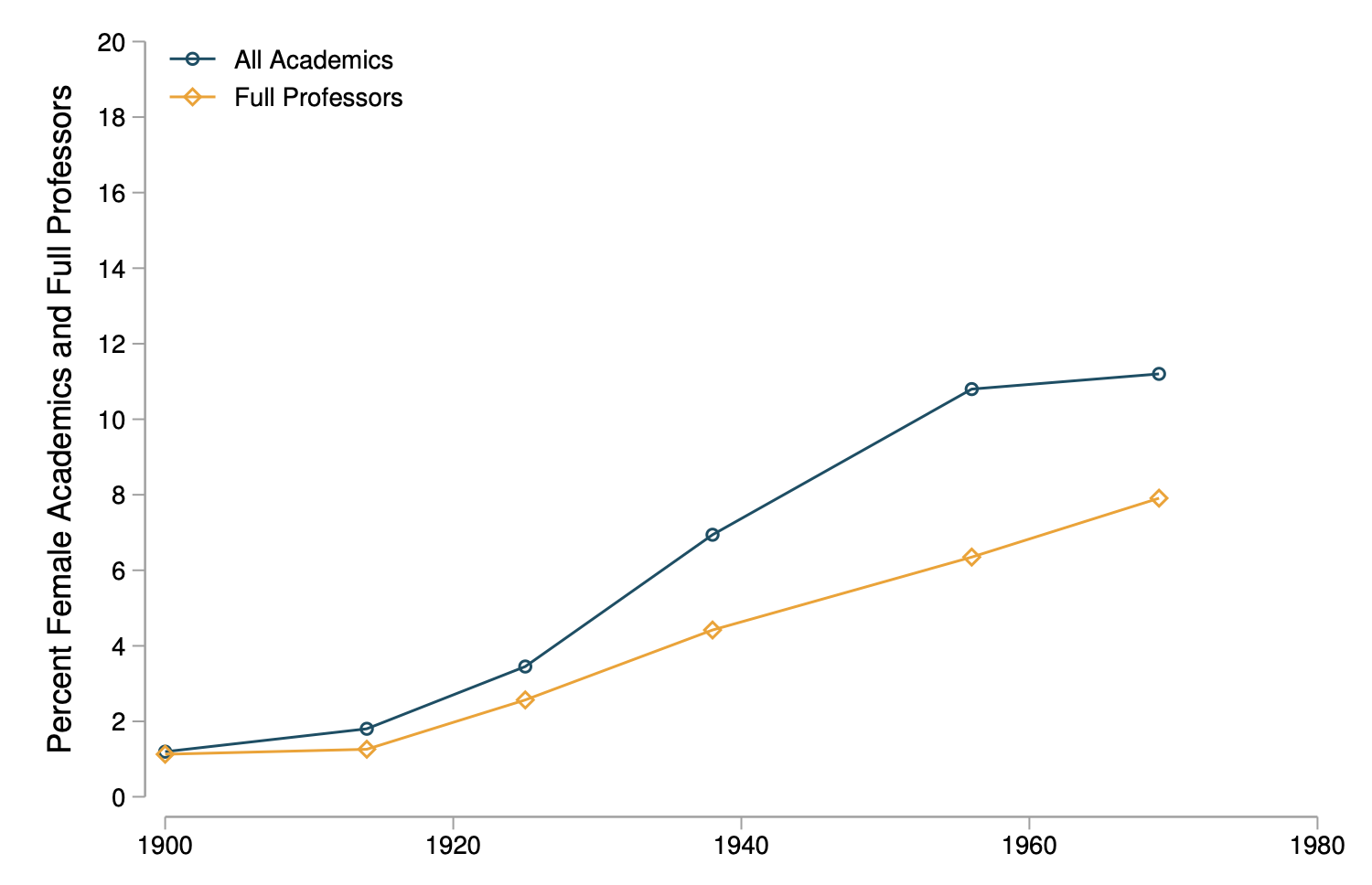

We first examine gender gaps in hiring. Across all universities and disciplines, our data reveal that in 1900 only 226 women were employed in academia, a share of only 1%. In the following decades, the proportion of women in academia increased gradually, rising to 2% in 1914, 3% in 1925, 7% in 1938, 11% in 1956, and 11% in 1969 (see Figure 1, Panel A).

When we focus on prestigious universities in three scientific disciplines (mathematics, chemistry, biochemistry), female shares were even lower until 1969. Between 1969 and 2000, female shares in the sciences in prestigious universities increased substantially, to 17.6% from about 3.3% (Figure 1, Panel B). Despite the increase over the last decades of the 20th century, women remain significantly under-represented in prestigious universities.

Figure 1 Gender gaps in hiring

a) All universities, 1900-1969

b) Prestigious universities, sciences, 1900-2000

Notes: The figure shows the percentage of female academics over time. Panel A shows female shares in all universities and disciplines until 1969. Panel B shows female shares in the sample of prestigious universities in the sciences (mathematics, chemistry, biochemistry) until 2000. See Iaria et al. (2022) for details.

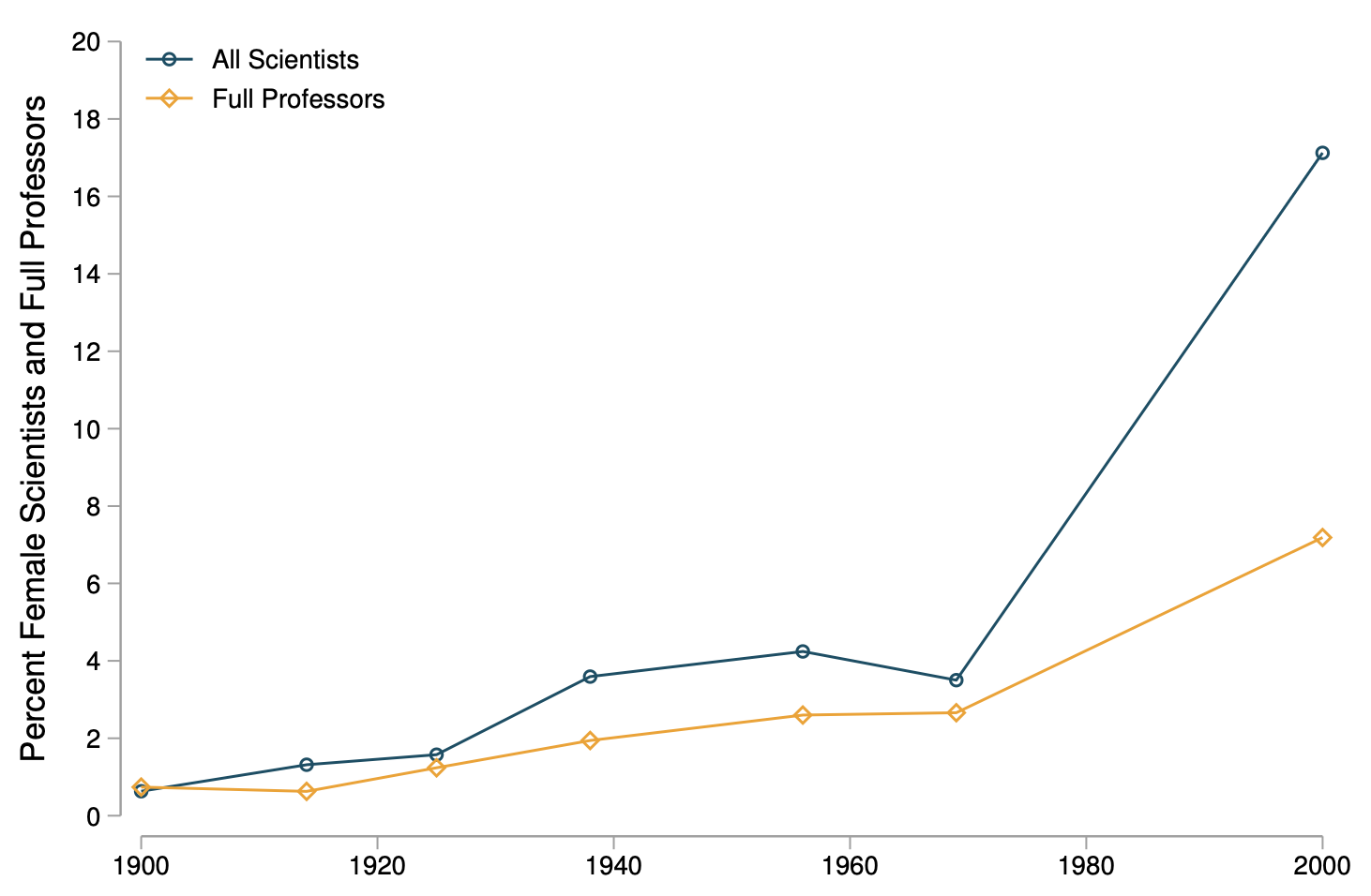

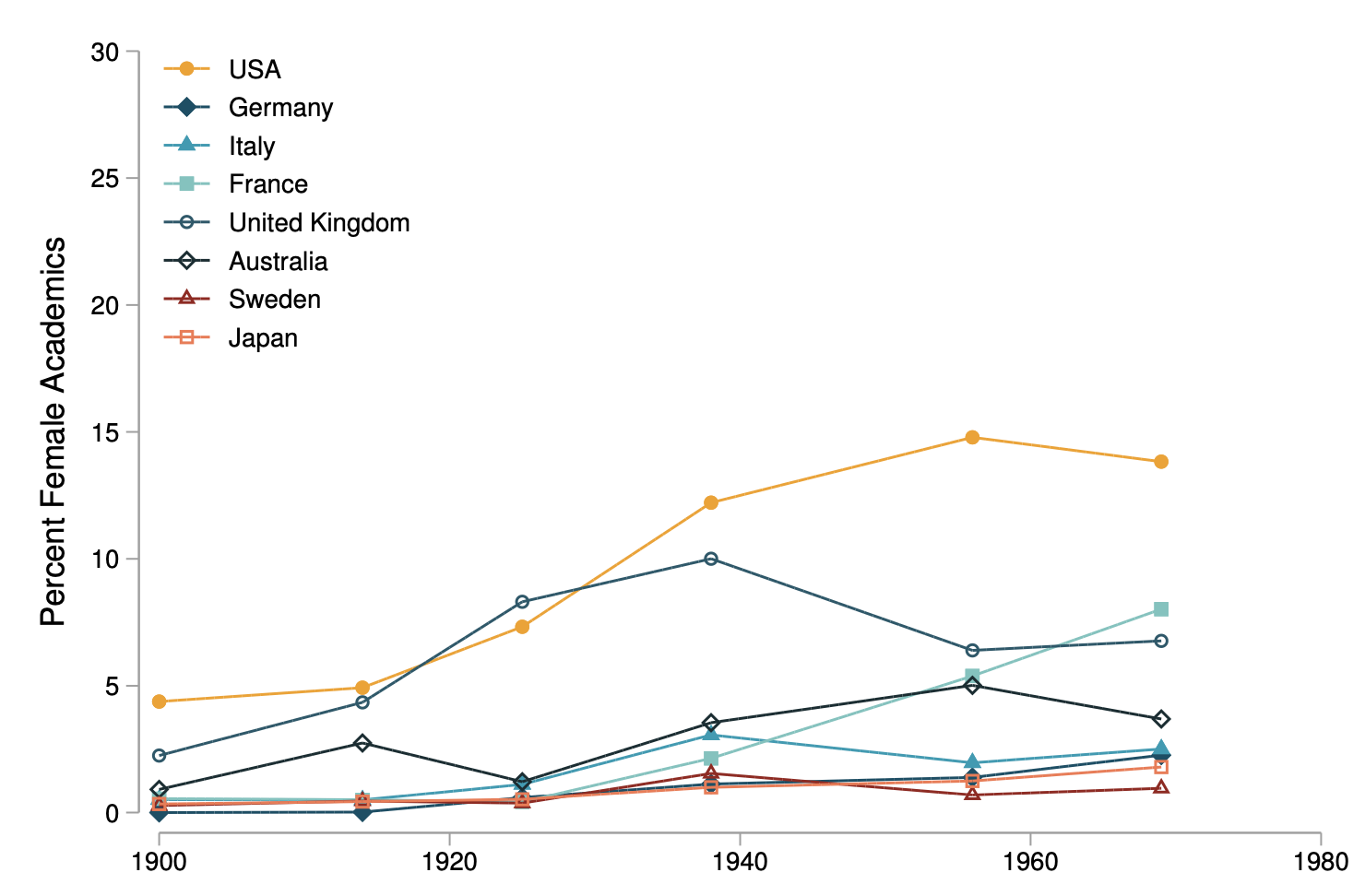

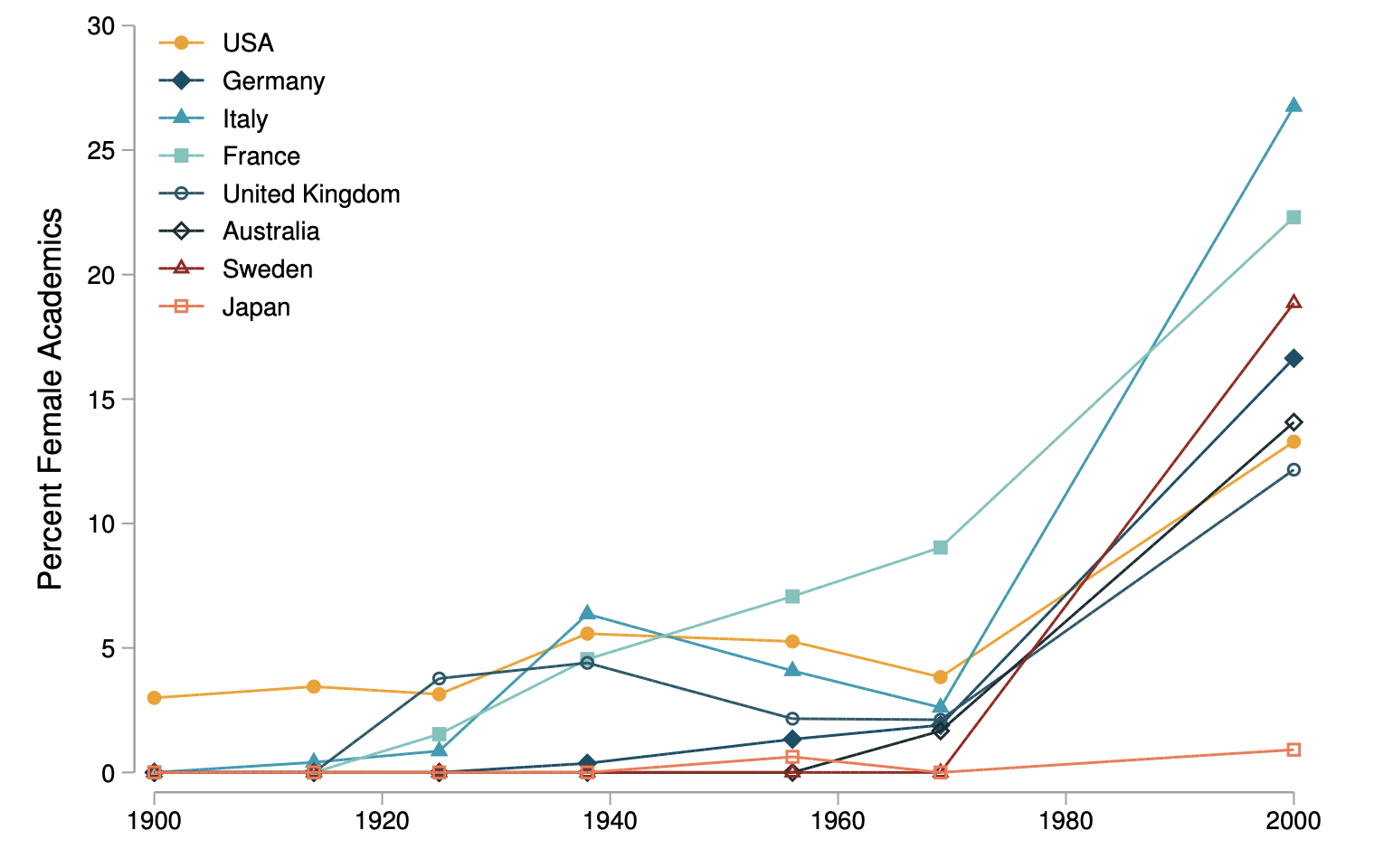

Globally, there is substantial heterogeneity in the share of female academics. Before WWI, universities in the US employed more female academics than any other country (Figure 2, Panel A). Overall, among all universities and disciplines, the dominant role of the US persisted until 1969. Among the prestigious universities, the early lead of the US in the sciences did not last, and by 2000 several other countries had hired more women in their prestigious universities.

Figure 2 Gender gaps in hiring across selected countries

a) All universities, 1900-1969

b) Prestigious universities, sciences, 1900-2000

Notes: The Figure shows the percentage of female academics by country and over time. Panel A shows female shares in all universities and disciplines until 1969. Panel B shows female shares in the sample of prestigious universities in the sciences (mathematics, chemistry, biochemistry) until 2000. See Iaria et al. (2022) for details.

The UK also had a relatively high share of female academics at the beginning of the 20th century but fell behind by 2000. In contrast, Scandinavian countries, and to a lesser extent Germany, had very low female shares until 1969 but increased their shares substantially in the three decades that followed. Italy had low shares before WWI, ranked in the middle until 1969, but increased its share substantially in the three decades until 2000. Japan is an interesting outlier: female shares were at similar levels during the first decades of the 20th century but, unlike the other advanced countries, Japan did not show a marked increase until 2000.

The cross-country evolution of female shares in academia was remarkably different from the evolution of female shares in the general workforce (e.g. Olivetti and Petrongolo 2016). This suggests that women’s academic careers were affected by factors different from those influencing women in lower-skilled professions.

Gender gaps in publishing

We next look at gender gaps in academic output, as measured by publications. One of the advantages of studying academics is the availability of output measures (i.e. publications) that are comparable across time and space. It is important to note that publications do not measure the true ability of academics. They summarise academic output that is influenced by preferences, discrimination, and other biases.

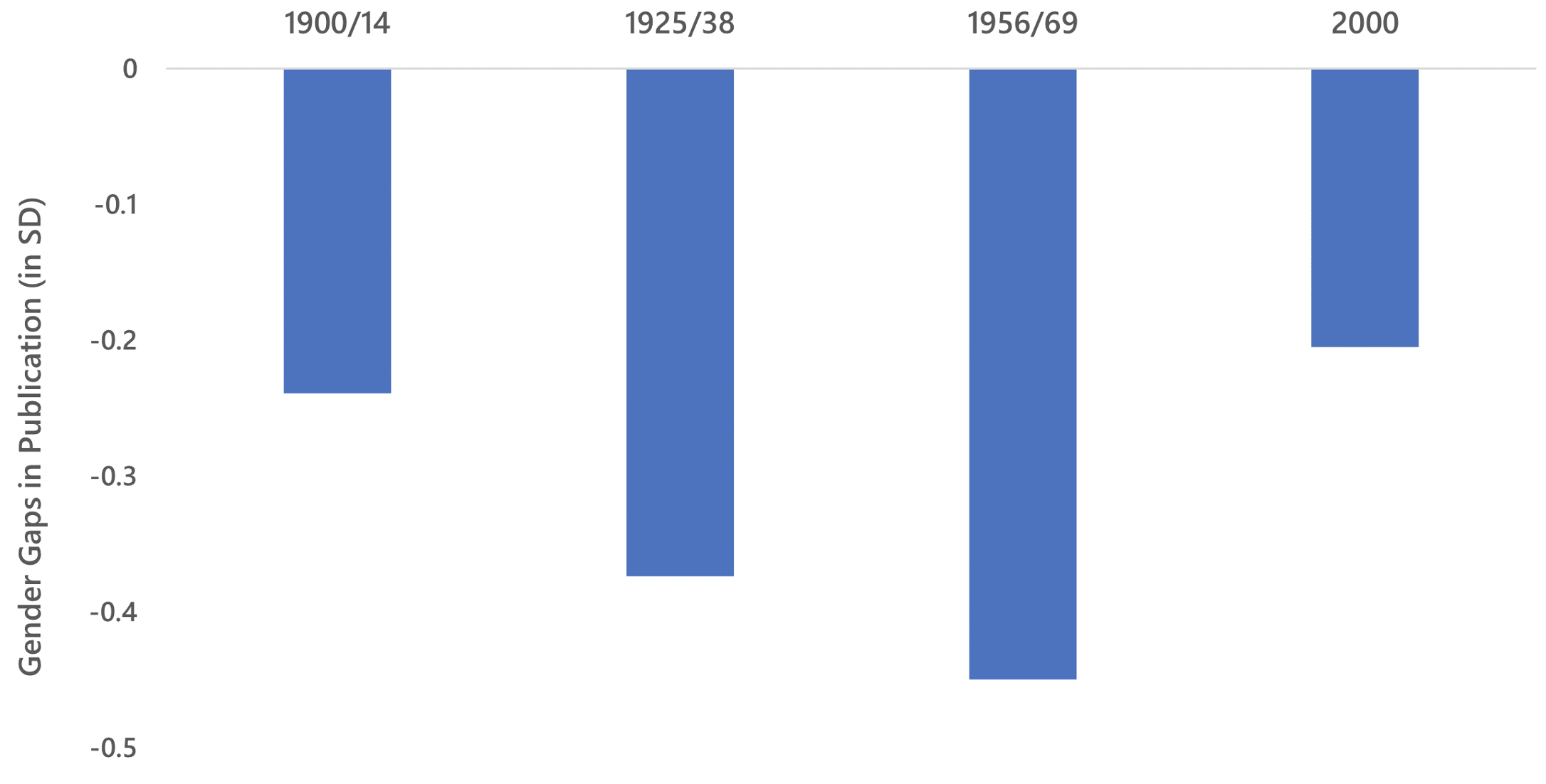

We find a U-shaped pattern of gender gaps in publications over time (Figure 3). The patterns described in Figures 1 and 2 suggest that the passing of time is, on average, associated with an increase in the share of women in academia. Therefore, it is possible that a pattern like the ‘gender U’ over time (Figure 3) could also hold with respect to an increase in the share of women in academia.

To explore this possibility, we propose a model along the lines of Roy (1951), which relates the share of women in academia to the observed gender gap in publications. We estimate the model and show that publication gaps are small or even positive for women in country cohorts with very low shares of female scientists: the ‘Marie-Curie’ country cohorts. However, as shares of women in the profession increased, gender gaps in publications became more negative. When the share of women increased beyond very low levels, the gender gap in publications decreased.

These findings suggest that the ‘gender U’ pattern can be rationalised by a Roy model. The model highlights how selection on unobservables and gender biases in hiring can indirectly affect estimated gender gaps in publication, in addition to any direct gender bias in publications.

Figure 3 Gender gaps in publications

Notes: The figure shows estimated gender gaps in publications over time using the sample of scientists (mathematicians, chemists, and biochemists) at prestigious universities. See Iaria et al. (2022) for details.

Gender gaps in citations

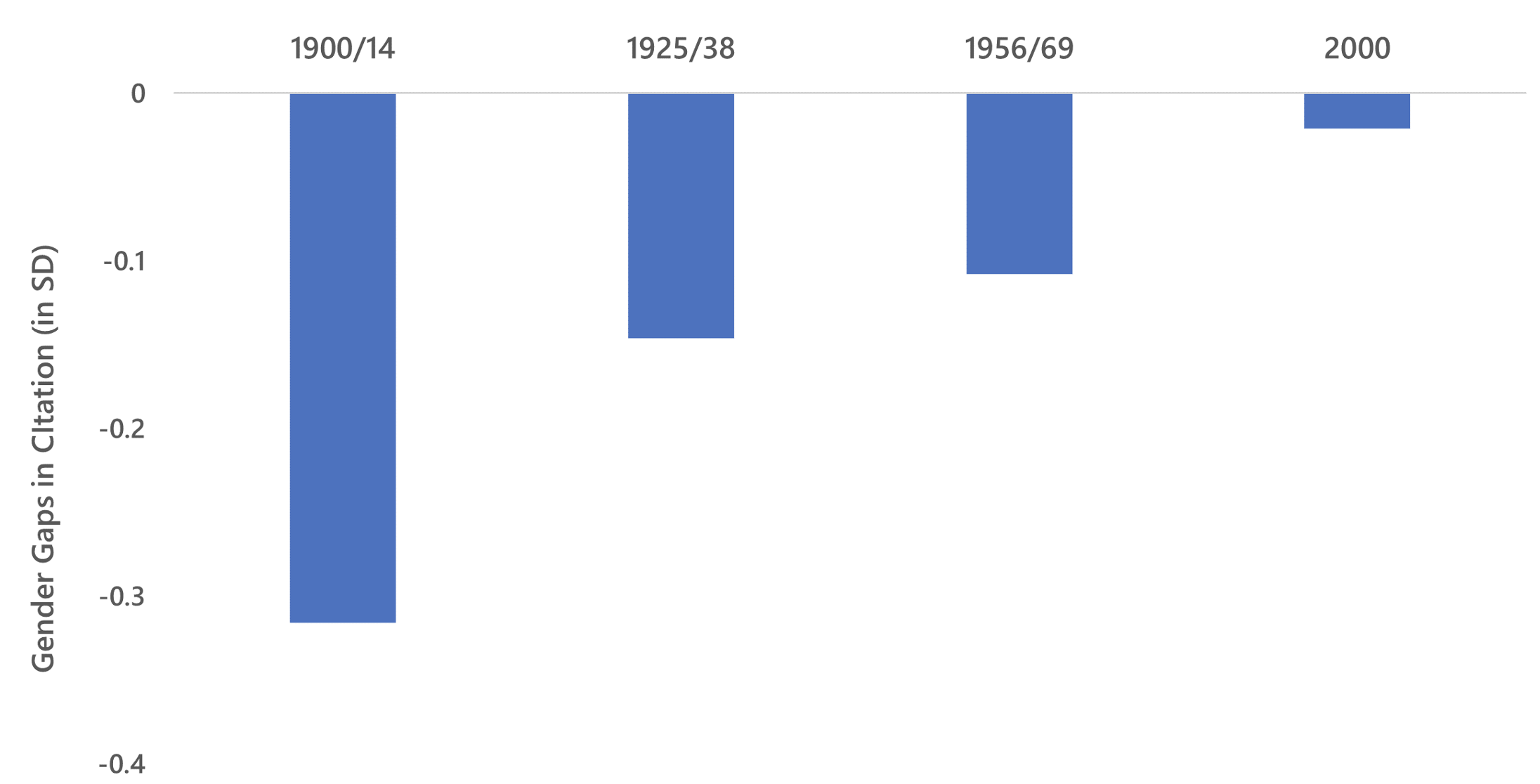

We also explore whether papers published by women received fewer citations. Machine learning is used to investigate whether potential citation gaps stem from gender differences in research topics. We train a regularised regression model that predicts the expected number of citations for each paper based on the words used in its title. To prevent the model from internalising biases against papers published by women, the training sample solely consists of papers published by men. As a consequence, the model predicts the citations of each paper as if it had been written by men.

The results show that, prior to WWI, papers by female authors received around 0.3 standard deviations fewer citations than papers by male authors. This gender gap holds even after controlling for the predicted citations of the paper, suggesting that citation gaps were not driven by differences in research topics. However, the gender gap in citations declined substantially over time and nearly disappeared by the year 2000 (Figure 4).

Figure 4 Gender gaps in citations

Notes: The figure shows estimated gender gaps in citations over time using all papers published by the sample of scientists (mathematicians, chemists, and biochemists) at prestigious universities. See Iaria et al. (2022) for details.

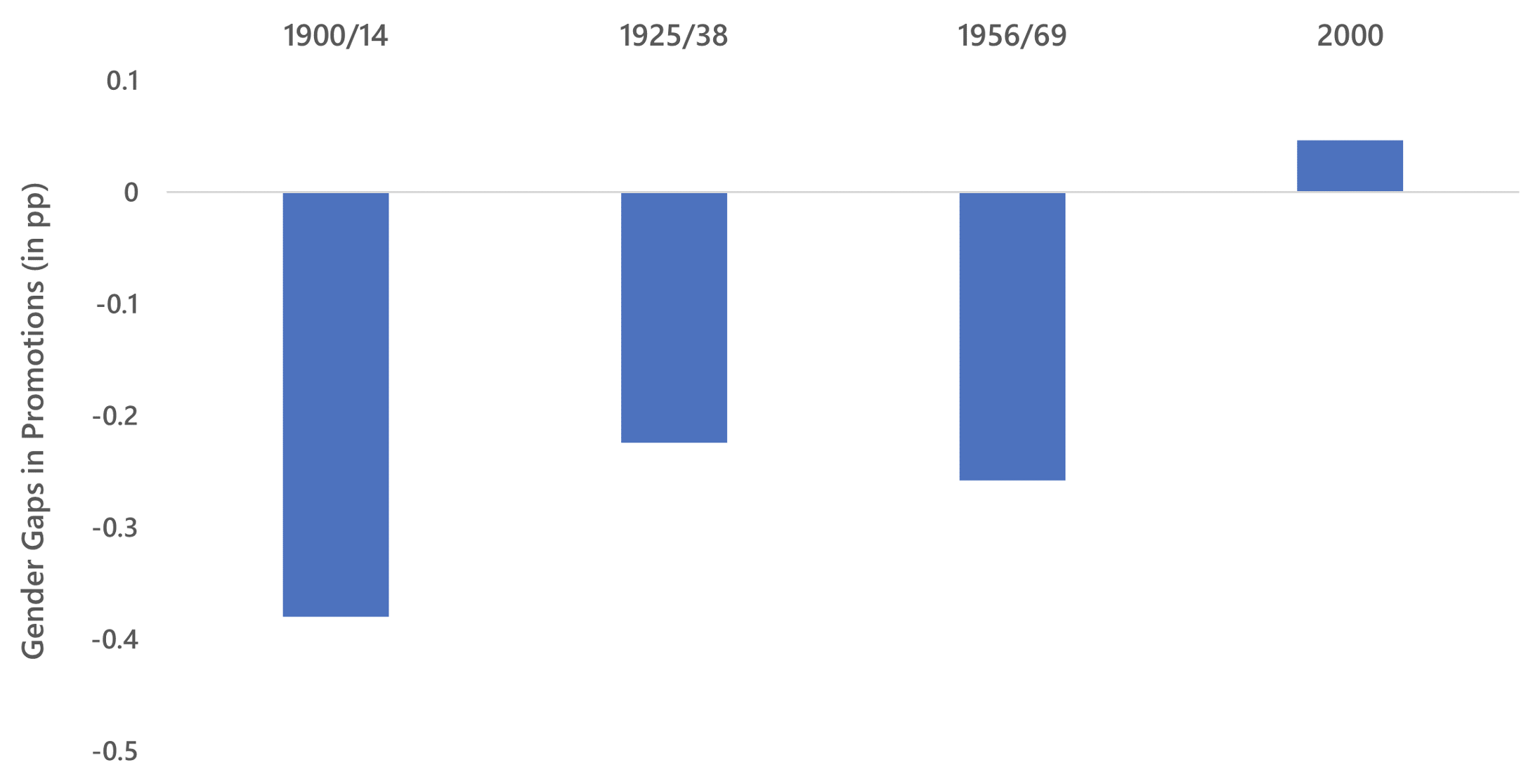

Gender gaps in promotions

Finally, we investigate how women progressed in their academic careers by analysing gender gaps in promotions. Our findings show that women were around 20–30 percentage points less likely to be promoted to full professor until the late 1960s. Strikingly, gender gaps in promotions remain similar even when we control for the scientist’s publication and citation record. This unexplained gender gap in promotions was larger than the effect of a five-standard-deviations-worse publication record. By the year 2000, the gender gap in promotions in the sciences had closed.

Figure 5 Gender gaps in promotions

Notes: The figure shows estimated gender gaps in promotion to full professor over time using the sample of scientists (mathematicians, chemists, and biochemists) at prestigious universities. See Iaria et al. (2022) for details.

Conclusion

In summary, we show the existence of significant gender gaps across four domains (hiring, publications, citations, and promotions) over the 20th century. However, our analysis indicates that gender gaps differ substantially across countries and disciplines, as well as domains and over time.

Our findings suggest that the substantial gender gaps in citations and promotions have declined to zero over the 20th century. In contrast, significant gender gaps still existed in hiring and publications, even toward the end of the century. Gender gaps in different domains are interconnected.

The documented barriers that excluded women from participating and contributing to scientific progress may have resulted in ‘lost Marie Curies’, depriving the world of valuable ideas and potential breakthroughs.

References

Bagues, M, M Sylos-Labini, and N Zinovyeva (2017), “Does the gender composition of scientific committees matter?”, American Economic Review 107(4): 1207–38.

Beidas, R S, P A Hannon, A S James, and K M Emmons (2022), “Advancing gender equity in the academy”, Science Advances 8(13): eabq0430.

Bertrand, M, S E Black, S Jensen, and A Lleras-Muney (2019), “Breaking the glass ceiling? The effect of board quotas on female labour market outcomes in Norway”, Review of Economic Studies 86(1): 191–239.

Card, D, S DellaVigna, P Funk, and N Iriberri (2020), “Are referees and editors in economics gender neutral?”, Quarterly Journal of Economics 135(1): 269–327.

Card, D, S DellaVigna, P Funk, and N Iriberri (2022a), “Gender differences in peer recognition by economists”, Econometrica.

Iaria, A, C Schwarz, and F Waldinger (2022), “Gender gaps in academia: Global evidence over the twentieth century”, CEPR Discussion Paper 17422.

Koffi, M (2021), “Innovative ideas and gender inequality”, Working Paper Series.

Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) (2021), “Inventors”, OECD Data.

Olivetti, C, and B Petrongolo (2016), “The evolution of gender gaps in industrialized countries”, Annual Review of Economics 8: 405–34.

Romanowicz, B (2019), “Equality of opportunity in the European Research Council competitions”, in EGU General Assembly Conference Abstracts 10306.

Ross, M, B Glennon, R Murciano-Goroff, E Berkes, B Weinberg, and J Lane (2022), “Women are credited less in science than are men”, Nature 608(7921): 1–2.

Roy, A D (1951), “Some thoughts on the distribution of earnings”, Oxford Economic Papers 3(2): 135–46.

Sarsons, H (2017), “Recognition for group work: Gender differences in academia”, American Economic Review 107(5): 141–45.

Sarsons, H, K Gërxhani, E Reuben, and A Schram (2021), “Gender differences in recognition for group work”, Journal of Political Economy 129(1): 101–17.