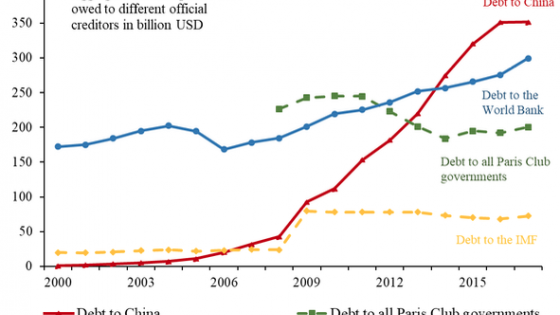

Since 2016, Chinese banks have represented the largest banking system in the world (Cerutti and Zhou 2018). Their foreign claims are substantial, although those seem relatively small when compared to their domestic business. Recently, in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic, China’s global claims have received special attention, triggered by discussions about the large sovereign indebtedness of some low-income countries (Horn et al. 2020, Graf von Luckner et al. 2021).

In this column, we shed some light on the global footprint of Chinese banks, which account for more than 35% of China’s claims on borrowers worldwide and almost 75% of the claims on emerging markets and developing economies (EMDEs).1

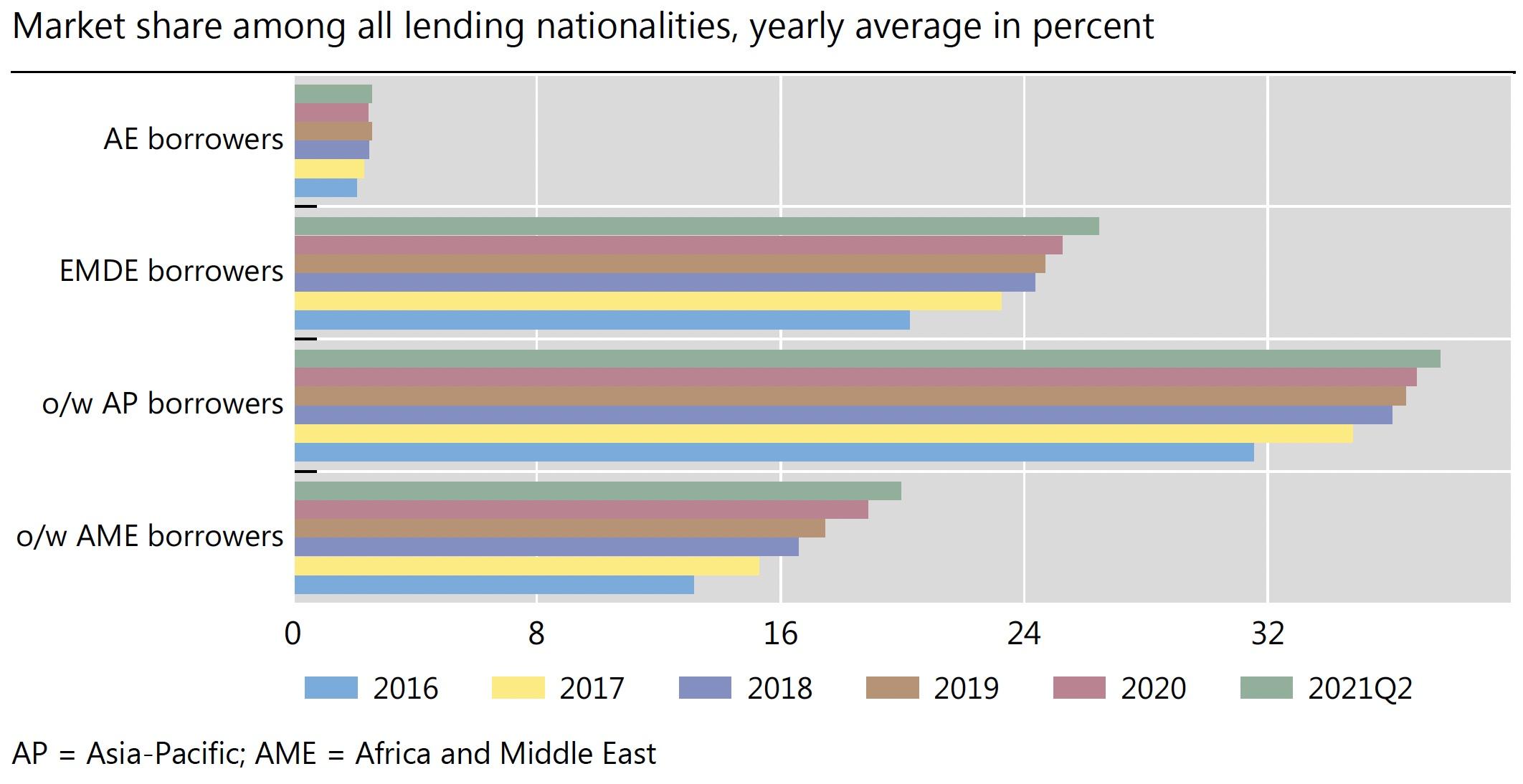

As of mid-2021, Chinese banks represent about 7.5% of global cross-border bank lending, and they reported claims on 175 out of 185 borrowing jurisdictions in the Bank for International Settlements (BIS) locational banking statistics. Their cross-border lending is particularly important for EMDEs: Chinese banks report bank claims on 133 out of 143 EMDEs, with a market share of more than 26% (Figure 1, green bar).

Figure 1 Cross-border lending by Chinese banks

Source: BIS Locational banking statistics (by nationality)

Moreover, 63 EMDEs already borrow more from Chinese banks than from any other bank nationality. By contrast, claims on advanced-economy borrowers held by Chinese banks are much smaller in relative terms. Their market share reaches just about 2.6%, and Chinese banks do not rank as top cross-border lenders to any specific advanced-economy borrower country.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, Chinese banks have grown their market share in cross-border lending to EMDEs. Borrowers in the Asia-Pacific region stand out with Chinese banks accounting for about 38% of their cross-border loans in 2021 Q2, up from about 32% five years ago. Chinese banks’ market share with borrowers in Africa and the Middle East also expanded at the expense of other major lenders. It climbed by 7 percentage points between 2016 and 2021, reaching 20% in mid-2021. Among borrowers in Eastern European and Latin American EMDEs, Chinese banks account for about 10% and 6%, respectively, also growing during the pandemic.2

These estimates take the global network of foreign affiliates into account. Foreign affiliates stand behind the global reach of international banks, and they are key to understanding the business. Banks lend across borders with loans booked either from the home country of their headquarters or by their affiliates (branches or subsidiaries) located abroad (either in financial centres or third countries/jurisdictions). The above estimates hence draw on the concept of bank nationality by attributing claims to the home country of parent banks.

As highlighted by Cerutti et al. (2018), across all bank nationalities, only about 60% of international banks’ cross-border lending is extended from their home country (about 62% in mid-2021). For banks from EMDEs, that share is about 55% in the latest quarter. Chinese banks also follow that pattern: a substantial part of their cross-border lending originates from affiliates operating outside mainland China.3

What else is different for Chinese banks? Their structure?

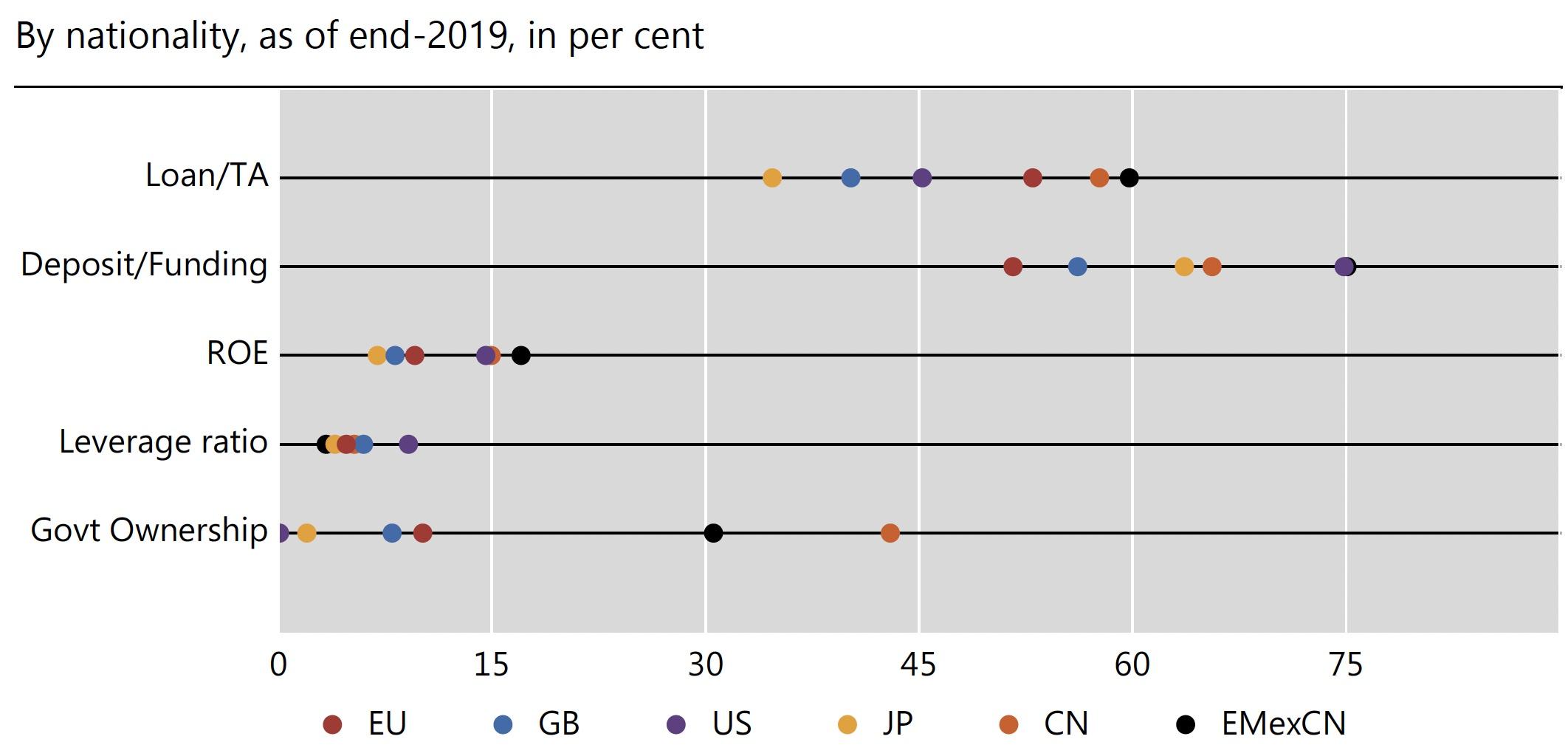

That said, how different are Chinese banks in terms of their balance sheet and funding structure? Similar to other banks from emerging markets, Chinese banks’ traditional business model and ownership structure distinguish them from typical advanced-economy banks. As of end-2019, loans constitute more than half of their assets, and they have a larger share of deposit funding than advanced-economy banks (see Figure 2). While the differences are less pronounced for other measures such as return on assets and leverage ratio, the strong presence of publicly owned banks is another key characteristic that differentiates Chinese and other typical EMDE banks from advanced-economy competitors.

Figure 2 Bank characteristics across banking systems

Notes: Based on the same of GSIB and DSIB banks in respective jurisdictions. EU comprises 42 banks of the following nationalities: Austria (2), Belgium (3), Denmark (3), Finland (1), France (6), Germany (9), Italy (5), Netherlands (2) Spain (8), and Sweden (3); GB Great Britain (5 banks), JP Japan (8), US (17), CN China (16 ); and EMexCN includes 23 banks of the following nationalities: Brazil(4), India(4), Indonesia(3), Korea (4), Mexico (1), Russia (3), South Africa (2), and Turkey (2).

Sources: Fitch Connect; Capital IQ; World Bank (Bank Regulation and Supervision Survey); authors’ calculations.

Mapping Chinese banks’ lending patterns and other economic ties

While following the literature by using a gravity approach, we analyse the geographical distribution of cross-border claims for the major bank nationalities, including Chinese banks. These models originate from the trade literature and have been frequently applied in empirical studies of cross-border finance (e.g. Aviat and Coeurdacier 2007, Buch 2002, Lane 2006, Lane and Milesi-Ferretti 2008, Okawa and van Wincoop 2012, Porter and Rey 2005).

Distance is a key, but bilateral trade and capital flows also matter in international banking. Previous studies (e.g. Brei and von Peter 2018) suggest that the geographical distance between the capitals of the lender and the borrower countries captures information asymmetries in cross-border banking. This also holds when extending this framework to the location of affiliates outside of the parent banks’ home country from which a specific bank nationality decides to make the loan.

While thereby going beyond the traditional gravity variables, we also find positive correlations between cross-border bank lending and bilateral economic ties, such as trade, foreign direct investment (FDI), and portfolio investment. Although the distance measure is new, the basic setup is in line with how portfolio flow studies proceed (e.g. Andrade and Chhaochharia 2010, Lane 2006, and Lane and Milesi-Ferretti 2008). By using either trade or FDI, these studies show that bilateral economic ties might also help to reduce information asymmetries between borrower and lender countries.

Our analysis shows that, despite some different bank characteristics and the fact that their expansion is more recent, Chinese banks’ global reach resembles that of advanced-economy banks, not only in terms of the importance of cross-border lending but also of the underlying key gravitational drivers. The few differences are linked to portfolio investment patterns that are very China-specific.

The main findings are:

- Chinese banks seem to perceive the distance to their borrowers in EMDEs as less of a barrier than other EMDE banks, comparable to US and European banks.

- The positive correlation between cross-border bank lending and bilateral trade of China with EMDE countries stands out. It is much stronger than the trade-lending relationship exhibited by Japanese and European banks, and it is more in line with patterns exhibited by US banks.

- Unlike all other banking systems, China’s past portfolio investment is negatively correlated with cross-border lending to EMDE borrowers. This seems linked to China’s capital outflow restrictions and the fact that Chinese portfolio investment is concentrated on few advanced-economy countries.

- Finally, there is only weak evidence on the relationship between China’s FDI and cross-border lending.

Implications

The growing international footprint of Chinese banks highlights the importance of understanding their global operations and business model. The strong positive correlation of Chinese banks’ cross-border lending with bilateral trade and their unusual current negative correlation with portfolio investment could interact with ongoing macroeconomic trends.

On the one hand, a prospective reduction in global trade (e.g. resulting from the shortening of global supply chains due to trade tensions and/or the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic) could be associated with a decline in Chinese cross-border bank lending, especially to EMDEs. On the other hand, the ongoing and planned liberalisation reforms in the Chinese bond market could foster further inward and outward portfolio investment.

If the liberalisation of portfolio investment makes China more similar to other countries, Chinese banks’ investments abroad could surge in an attempt to further diversify. This, in turn, could lower information asymmetries for Chinese cross-border bank lending.

Authors’ note: This column is mostly based on Cerutti et al. (2020). The views expressed in this column are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the Bank for International Settlements or the IMF.

References

Andrade, S C, and V Chhaochharia (2010), “Information immobility and foreign portfolio investment”, Review of Financial Studies 23(6): 2429−63.

Aviat, A, and N Coeurdacier (2007), “The geography of trade in goods and asset holdings”, Journal of International Economics 71: 22-51.

Brei, M, and P von Peter (2018), “The distance effect in banking and trade”, Journal of International Money and Finance 81(March): 116–37.

Buch, C (2002), “Are banks different? Evidence from international data”, International Finance 5(1): 97–114.

Cerutti, E, C Koch and S K Pradhan (2018), “The growing footprint of EMDE banks in the international banking system”, BIS Quarterly Review, December.

Cerutti, E, C Koch and S K Pradhan (2020), “Banking across borders: Are Chinese banks different?”, IMF Working Paper 20/249 and BIS WP 892.

Cerutti, E, and H Zhou (2018), “The Chinese banking system: Much more than a domestic giant”, VoxEU.org, 9 February.

Horn, S, C M Reinhart and C Trebesch (2020), “China’s overseas lending and the looming developing country debt crisis”, VoxEU.org, 4 May.

Graf von Luckner, C, J Meyer, C Reinhart and C Trebesch (2021), “External sovereign debt restructurings: Delay and reply”, VoxEU.org, 30 March.

Lane, P (2006), “Global bond portfolios and EMU”, International Journal of Central Banking 2(2): 1–23.

Lane, P, and G M Milesi-Ferretti (2008), “International investment patterns”, Review of Economics and Statistics 90(3): 538–49.

Okawa, Y, and E van Wincoop (2012), “Gravity in international finance”, Journal of International Economics 87(2): 205–15.

Portes, R, and H Rey (2005), “The determinants of cross-border equity flows”, Journal of International Economics 65: 260–96.

Endnotes

1 These figures draw on official data reported to the BIS Locational Banking Statistics, the IMF Coordinated Portfolio Investment Survey and the IMF Coordinated Direct Investment Survey as of end 2019.

2 In terms of being the most significant lender, 28 of the 63 EMDEs that borrow more from Chinese banks than from any other bank nationality are in Africa and Middle East, 22 are in Asia and the Pacific, eight are in Latin America, and five in Eastern Europe.

3 About one-quarter of Chinese banks’ cross-border lending to EMDEs originates from affiliates operating outside mainland China, Hong Kong SAR, Macao SAR, and Taiwan Province of China.

4 Cerutti et al. (2020) present an alternative and novel distance measure by weighting across all locations (home and/or affiliates abroad) from where a given bank nationality extends claims on a specific borrower country. This alternative measure seems to perform better than simple geographical distances between the banks’ headquarters and the borrowing countries.