While globalisation has enabled both the growth of poorer countries and access to cheaper consumer goods in richer ones, many worry that the effects of trade – and particularly import competition – have been poorly distributed across individuals in developed countries. At the core of an important literature (Autor et al. 2013a, 2014, 2016, Ebenstein et al. 2014, Pierce and Schott 2016), the ‘China shock’ has been shown to lead locally to higher unemployment, lower labour force participation and reduced wages.

Spatial heterogeneity of the local labour market impact of the China shock

In a recent paper (Adda and Fawaz 2020) we build on and extend this body of work, showing that the labour market effects of import competition are mediated by the average routine task intensity (RTI) in the manufacturing sector in the area. In areas where this intensity is low, import competition has no discernible effects on employment, unemployment, or family income. In contrast, manufacturing workers in areas where jobs are more routine-intensive are under the double pressure of plants closing down due to a shrinking domestic market and an automation process threatening the existence of their jobs. We find that the higher the average RTI, the higher the adverse impact of the import shock on manufacturing decline, employment, unemployment, non-employment, and family income.

The dynamic effect of import competition

We show that not only do import shocks have a lasting effect of many years, but their effect on employment and income also increases with time – in some cases, the effect doubles within a span of six years. This feature shows that import competition is of a different nature to other aggregate shocks, that tend to be less persistent over time.

A detailed picture of the effect of import shocks on health, health behaviour, access to health care, and mortality

Our results complement a new strand of the literature that has been looking directly at the impact of import competition on workers’ health (Colantone et al. 2015, Lang et al. 2019, Adda and Fawaz 201), Pierce and Schott 2020), but we offer a more comprehensive and detailed view of the health effects.

Our empirical analysis draws on multiple large datasets that record individual health in the US over the last decades. We exploit data from the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS) to get information on morbidity, interactions (or the lack of) with the health care system, and health behaviour. We complement these data with 40 million hospital records (HCUP) with detailed medical diagnosis to shed further light on the effect of import competition on morbidity, poor health behaviour, and health care access. Finally, we use longitudinal data following manufacturing workers to investigate the effect of import competition on mortality (NHIS restricted mortality files). We investigate how the geographical concentration of economic effects and their dynamics affect the disparity and timing of a large set of health outcomes.

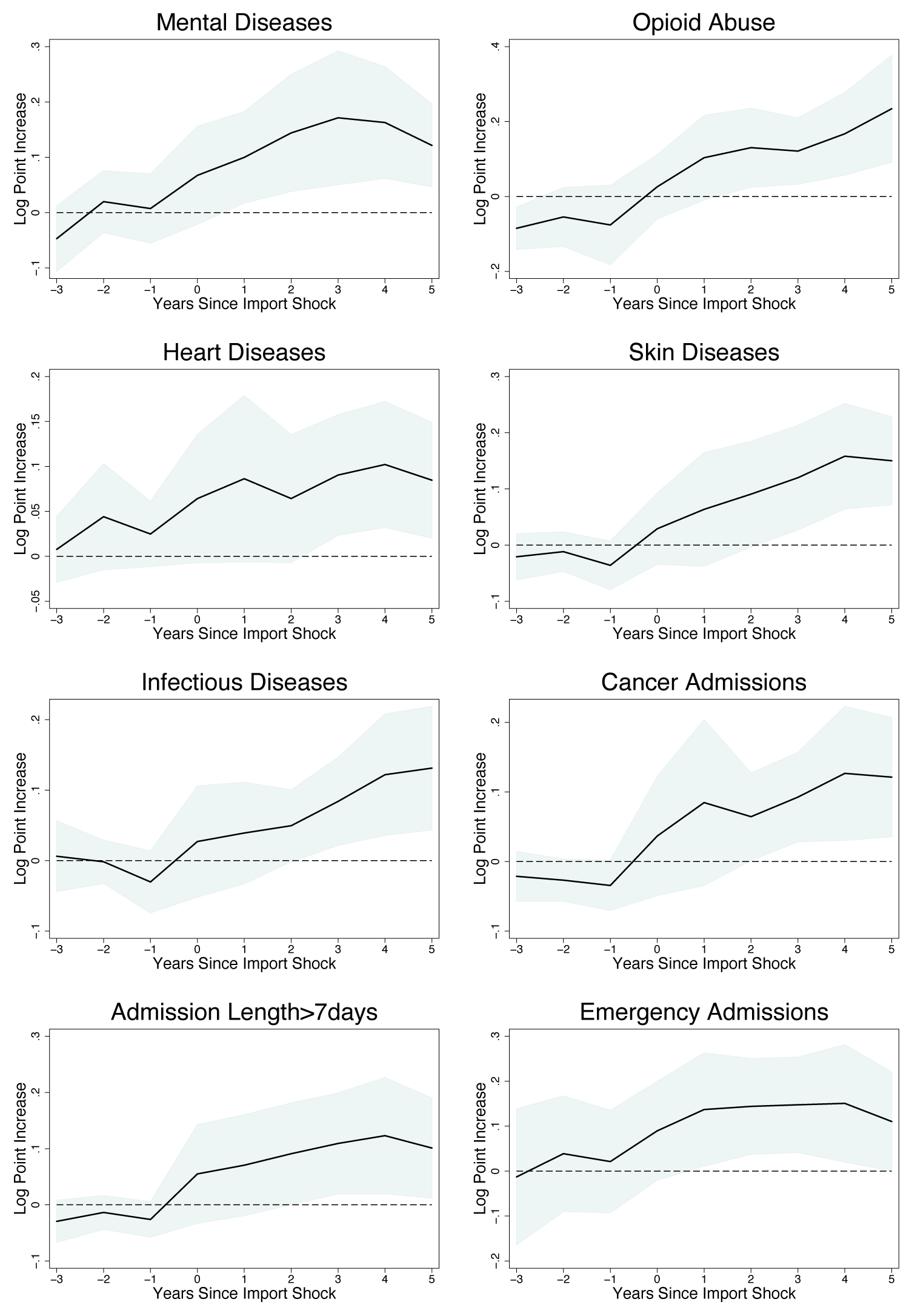

We show that the effects of import competition on health are restricted to precisely those areas where manufacturing jobs are more routine-oriented. The effect of import competition on health is also increasing in the timing of the import shock, and affects both physical and mental health (see Figure 1). As documented by Colantone et al. (2015) here on Vox, the effect of import competition is particular strong for mental health problems; we find the same is true for substance abuse, and especially opioid abuse. We also document a rise in the occurrence of pain related to import competition in high RTI areas, with the most frequent issues being chronic pain, backache, and chest pain. Our results also show increased rates of hospitalisation due to heart problems, infectious diseases, or respiratory diseases. The most common respiratory diseases include asthma and pneumonia, conditions which are linked to, among others, stress and lack of preventive care. We find a large effect on skin diseases, where a leading cause is skin infections, often linked to diabetes or obesity. The effect is lower but still significant for endocrine diseases. The most common endocrine diseases in our data are diabetes and hypercholesterolemia, two conditions related to poorer health behaviour. In addition, we find an increased rate of admissions related to cancer. The effect of import competition on health is considerably lower in areas with low or medium RTI and often not significant.

Figure 1 Import shocks and hospital admissions in high RTI areas

Notes: The figures displays the coefficients and 95 percent confidence intervals for the effect of import competition on different hospitalisation outcomes. The data is drawn from National Inpatient Sample. All regressions are done separately for outcomes and for lags or leads of the import shock. All regressions include hospital, year, socio-demographic fixed effects, and control for state trends, time varying commuting zone and county characteristics.

The results are remarkably similar across the different data we use, coming either from survey data or from larger hospital records. We then investigate the possible pathways leading from poorer labour market outcomes to poorer mental and physical health. We find mixed effects of import competition on health behaviour – on average, they improve following an import shock, but at the same time, there is a worsening in the upper tail. Uncovering this complex pattern requires a very large sample size of hospitalisation data, as health surveys such as the BRFSS miss it.

Pathways from import competition to health

We show that the decline in health is too large to be explained by the observed decrease in family income. Another channel might be the reduced interaction with the healthcare system that we document. Two factors could be at play: the decrease in family income; and the loss of the employer-provided health insurance, which – in the case of the US – is not replaced by public coverage in most cases. We show that the decrease in income is not enough to explain the reduction in care. The consequence of this lack of access is that it may lead to some health conditions going untreated or being diagnosed too late, leading to more serious conditions later on. Our analysis of the hospitalisation data reveals that import shocks lead patients to be admitted with more serious conditions that require longer treatments. Finally, we show that increases in import competition have a subsequent effect on mortality that grows over time. By analysing individual and longitudinal data, we can rule out prior sorting into industries based on health. The results show that a one billion dollar increase in imports raises the hazard of dying by about 6% after seven years.

References

Adda, J, and Y Fawaz (2019), “Trade Induced Mortality”, L’Actualité économique 95(1): 6-29.

Adda, J and Y Fawaz (2020), “The Health Toll of Import Competition”, The Economic Journal 130(630): 1501–1540.

Autor, D H, D Dorn, and G H Hanson (2013), “The China Syndrome: Local Labor Market Effects of Import Competition in the United States,” American Economic Review 103(6).

Autor, D H, D Dorn, G H Hanson and J Song (2014), “Trade Adjustment: Worker Level Evidence,” Quarterly Journal of Economics 129(4): 1799–1860.

Colantone, I, R Crino, and L Ogliari (2015), “Globalization and Mental Distress,”, mimeo Bocconi University (accepted at the Journal of International Economics).

Colantone, I, R Crino, and L Ogliari (2015), “Import competition and mental distress: The hidden cost of globalization”, VoxEU.org, 4 December.

Ebenstein, A, A Harrison, M McMillan, and S Phillips (2014), “Estimating The Impact of Trade and Offshoring on American Workers Using The Current Population Surveys,” The Review of Economics and Statistics 96(4): 581–595.

Lang, M, T C McManus, and G Schaur (2019), “The effects of import competition on health in the local economy,” Health Economics 28(1): 44–56.

Pierce, J R and P K Schott (2016), “The surprisingly swift decline of US manufacturing employment,” American Economic Review 106(7): 1632–62.

Pierce, J R and P K Schott (2020), “Trade liberalization and mortality: Evidence from US counties,” American Economic Review: Insights 2(1): 47-64.