How can people be empowered to make better financial decisions? Working with CEPR’s Household Finance Network, the Think Forward Initiative (TFI) has been seeking to build a bridge between research insights and action by the financial services industry and households themselves. Some of the results were presented at the second TFI Summit in Munich in March 2017, focused around three broad themes: daily financial affairs (budgeting, spending, and borrowing); finance for the future (savings, investment, and retirement); and financial literacy.

Money can buy happiness

A keynote address by social psychologist Michael Norton of Harvard Business School explored the relationship between money and happiness. His central message – if you think money can’t buy happiness, you’re not spending it right – was followed up by a series of research-based principles that can help people to get more happiness out of their money (Dunn and Norton 2013).

One of Norton’s principles of spending for greater happiness is to buy experiences, not material goods. Reflecting on their lives, people are much more likely to list memories of vacations, rather than buying cars, as valuable moments – particularly if these items on their ‘experiential CV’ were shared.

Another principle is to invest in others, shifting the focus outwards either through buying gifts for friends and family or donating to charity. Research in 136 countries finds that, for the most part, people who have donated to charity in the previous month report greater satisfaction with life (Aknin et al. 2013).

Social norms and financial decisions

Developing the theme of giving to charities, Norton described his research on how donors can be encouraged to move from making a one-off contribution to committing to recurring donations over the longer term. ‘Contingent match incentives’ constitute a new approach to fundraising in which matching is made contingent on the percentage of others who give – for example, ‘if X% of others give, we will match all donations’.

A field experiment shows that a 75% contingent match – where matches ‘kick in’ only if 75% of others donate – is most effective in increasing commitment to recurring donations. An online experiment reveals that the 75% contingent match drives commitment to recurring donations because it provides both social proof and a low enough target that it remains plausible that the match will occur. A final online experiment demonstrates that the effectiveness of the 75% contingent match extends to one-time donations (Anik et al. 2014).

Other research on charitable giving indicates that it can be influenced by the amount of previous donations – not just because people copy others, but because they want to be perceived in a certain way. The study shows that a single large donation of £100 on an online fundraising website increases subsequent amounts given by around £10 and can pay back in ten donations’ time (Smith et al. 2015).

There is evidence that such peer effects can have a big impact on other financial decisions – for better or worse. One study of venture capitalists finds that those who choose to collaborate with fellow graduates that invest wisely make better investment choices themselves; those who make a poor choice of peers do worse (Gompers et al. 2012).

Another study looks at how peer effects can alter long-term savings decisions: a new law in Israel gave people the option to move to a multitude of other pension funds or stay with their employers’ pension plans. A vast majority (93%) of over 10,000 employees studied chose to remain with their company programme. But among those who did switch, many chose funds that offered worse terms than the old one. By far the most popular fund chosen by those employees who switched did not stand out in terms of performance, transaction costs or services (Mugerman et al 2014).

Apps for better financial decisions

The study of peer effects and savings decisions relates to one of five TFI projects from which preliminary research findings and proposed practical solutions were presented at the Summit. Marieke Blom of ING and Nick Watkins of the Money Advice Service are exploring how people might change their saving behaviour when they can compare what they do to how much their friends save – what the researchers call a ‘social norm nudge’.

Like some of the other TFI projects, the proposed solution is an app that can help people evaluate their financial decisions against some external benchmarks – in this case, a peer comparative savings app that helps people to be in control of their savings by reducing the pitfall of having short-term pleasures win over long-term needs.

Another of the five TFI projects is examining the impact of emotions and social influence on borrowing behaviour through social media conversations and machine-learning predictive analytics. With the aim of using social media to anticipate and avoid harmful borrowing, the project team proposes a tool built into a browser or shopping app that helps determine whether the user can afford something before they buy it. The app simply says ‘yes’ or ‘no’, with an explanation based on social media analysis. Research suggests that this is a very reliable predictor of financial delinquency.

A third TFI project on financial literacy is investigating how to support people by providing appropriate financial services as well as financial education to improve their financial capability. Again, the proposed solution is an app that facilitates better informed financial decision-making, helping users to break down big decisions into manageable chunks and providing personalised tips grounded in research.

Financial decision-making within families

Norton concluded his keynote address by asking Summit participants to think about what percentage of people’s assets (savings, credit cards, mortgage, etc.) they have combined with their partner or spouse – and then how happy they are with their relationship. He noted that research indicates a high correlation between the degree of partnership in finances and the level of satisfaction with the relationship.

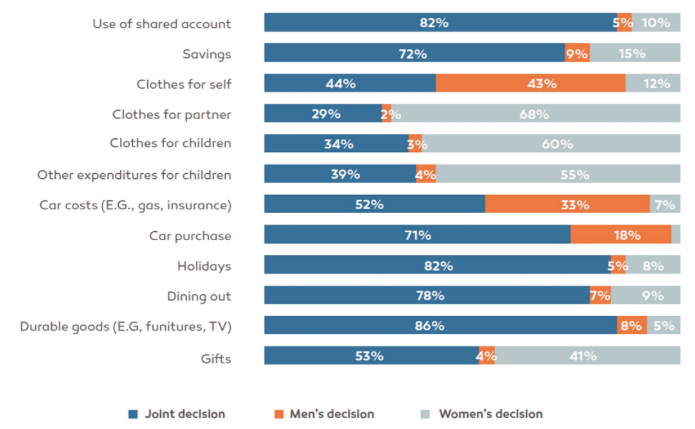

This result relates to another of the five TFI projects. In a study of family decision-making about financial affairs, Tilburg University economic psychologist Fred van Raaij and colleagues conducted a survey of around 1,000 Dutch couples. Their main conclusion confirms previous evidence (e.g. Simpson et al. 2012): many decisions – from choosing clothes for children to looking for a new job or buying a house – are joint decisions with partners, children, or other family members. As many as 86% of husbands claim that the purchase of durable goods is a joint decision. Even for personal items such as clothes, a substantial portion of respondents answered that the decision is taken jointly with their partner (see Figure 1).

Figure 1 Who makes decisions in the household?

Source: Van Raaij and Pan (2017)

Given that households are where most financial decisions are made, the research looks into the differences in the roles that husbands and wives play in the decision-making process. The results show that women have relatively strong bargaining power within their households, and men are more likely to overestimate their influence. Around 14% of women claim that they are the decision-maker when it comes to shared accounts, and this is more or less confirmed by their partners’ answer, as 10% of men admit this as well. Only 5% of men claim that they are the decision-makers on shared accounts.

The situation is similar with decisions on savings, where around 16% of women claim that they are the decision-makers and the corresponding number for men is only 9%. Out of the 10 consumption items in Figure 1, men make all or most decisions regarding an average of 1.1 of them; for women, this number is 2.06. While men claim that they are the main decision-maker, their wives only agree in 59% of cases; when it’s vice versa, the percentage reaches 68%. Men seem to be more likely to overestimate their influence on expenditure decision-making in their households.

Future self

The fifth TFI project – led by Dimitris Mavridis of the University of Luxembourg and Stefan van Woelderen of ING – is based on the idea of ‘live for today, prepare for tomorrow’. The ambition is to build a better understanding of how people think about their ‘future self’, and then to develop an app that functions as a personal coach, visualising possible future narratives, to help people to plan their own life, stay on track, and get financial peace of mind by showing the path towards long-term financial goals.

The first requirement is an understanding of the variety of responses to major life events across the population. For example, a divorce can open new positive opportunities for one person but be devastating for another. The financial consequences can differ sharply as a result of personality traits and differences in people’s social and financial situations and their outlook on life.

Moreover, life events that are normally not considered significant for long-term finances could have surprisingly big impacts on spending patterns and long-term savings. For example, there is evidence that gaining or losing weight, and the social consequences related to that, can be financially more significant for some than major life events such as giving birth or getting married.

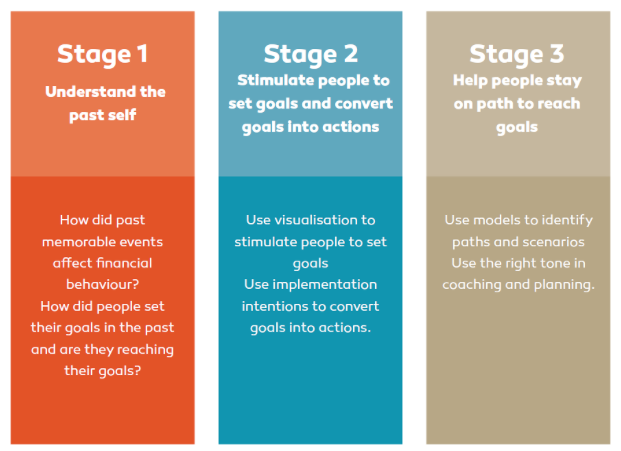

Figure 2

Source: Mavridis and Van Woelderen (2017)

The Future Self project is in three stages. Stage one uses models from psychology and a household survey to understand evidence from the past (‘past self’), combine it with the current situation (‘current self’), and predict how that relates to a person’s ‘future self’.

Stage two will be about stimulating people to set goals and converting those goals into actions. The aim is to find out more about the extent to which visualisation and personalisation help or hinder people to set goals; and how that differs between types of goals. This stage will also be about helping individuals translate good intentions into action. Randomised controlled trials could be used to test whether specifying implementation intentions helps people to turn goals into actions.

Stage three will be about helping people to stay on track to reach their goals. In terms of research, this phase will be about understanding the paths people need to take to reach their goals and to understand how a practical tool can help people stay on track, particularly in response to unexpected life-changing events.

References

Aknin, L, C Barrington-Leigh, E Dunn, J Helliwell, J Burns, R Biswas-Diener, I Kemeza, P Nyende, C Ashton-James and M Norton (2013), “Prosocial Spending and Well-being: Cross-cultural Evidence for a Psychological Universal”, Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 104(4): 635-52.

Anik, L, M Norton and D Ariely (2014), “Contingent Match Incentives Increase Donations”, Journal of Marketing Research 51(6): 790-801.

Dunn, E and M Norton (2013), Happy Money: The Science of Smarter Spending, Simon & Schuster.

Gompers, P, V Mukharlyamov and Y Xuan (2012), ‘The Cost of Friendship’, NBER Working Paper No. 18141.

Mavridis, D and S Van Woelderen (2017), “The future self”, Think Forward Initiative.

Mugerman, Y, O Sade and M Shayo (2014), "Long Term Savings Decisions: Financial Reform, Peer Effects and Ethnicity", mimeo.

Simpson, J, V Griskevicius and A J Rothman (2012), ‘Consumer Decisions in Relationships", Journal of Consumer Psychology 22(3): 304-14.

Smith, S, F Windmeijer and E Wright (2015), "Peer Effects in Charitable Giving: Evidence from the (Running) Field", Economic Journal 125(585): 1053-71.

Van Raaij, F and L Pan (2017), “Teamwork: Dutch couples make most financial decisions together”, Think Forward Initiative.