With the advance of the digital economy, an increasing number of companies are facing changing business characteristics. As the uncertainty and complexity surrounding technological trends and the global situation grow, risks are increasing for business strategies that depend entirely on traditional business models. As a result, companies in infrastructure and smokestack industries have also started to invest in new businesses which were previously unfamiliar to them, and are eagerly engaging in open innovation and business partnerships.

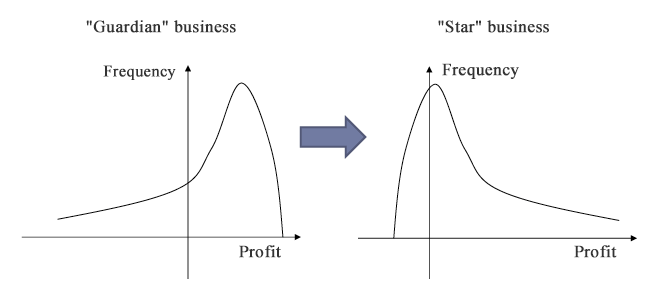

Changes in business characteristics alter the optimal personnel management system. For example, let us define two simple different business categories which we call ‘guardian’ and ‘star’ businesses (Barron and Kreps 1999). Figure 1 shows the distribution of corporate profit for the two. We define businesses whose upside potential is limited, but downside risk is significant, as ‘guardian businesses’. Typical examples include infrastructure companies, including power generation, communication and transportation companies. On the other hand, for ‘star’-type companies, downside risks are limited, while their corporate value may rise much higher than expected if their business proves successful. Platform companies as represented by Google, Amazon, Facebook, Apple and other companies that have the potential to create new markets belong to the ‘star’ type.

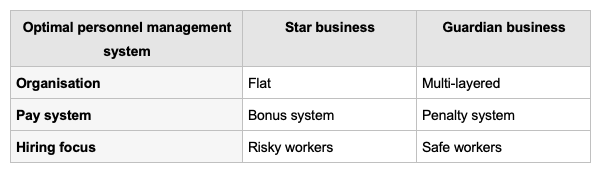

The personnel management systems that are optimally suited to these two types of businesses are entirely different. As shown in Table 1, whereas a flat organisation that enables prompt decision making is desirable for star-type businesses, a multi-layered organisation that reduces the risk of making mistakes is necessary for guardian-type businesses. For stars, a bonus system that encourages risk-taking – namely, a system that rewards employee contributions to profits but does not penalise them for failures – is desirable, because risk-taking raises the option value of the business. For guardians, the best pay system is a penalty system which punishes mistakes in order to discourage risk-taking. The two types of businesses also need individuals of different talents. Stars need workers who have high growth potential but may lack track records and workers with diverse backgrounds (‘risky workers’). In contrast, guardians need workers with qualities such as stability and reliability (‘safe workers’) and shun diversity, which is considered to hamper smooth coordination (Lazear 1998).

Figure 1 Two types of businesses with different characteristics

Table 1 Business category and the optimal personnel management system

Tendency to overvalue safe workers

Although the advance of digitisation may be increasing the share of stars in the economy as a whole, it appears that many companies have largely maintained the same hiring policies and practices, and still refrain from hiring workers with diverse and uncertain profiles.

In my many years of experience teaching at Japanese and US business schools, I have noticed that MBA students' attitudes toward hiring differ significantly between Japan and the US. For example, when given the hypothetical choice of hiring job applicant A who has a 100% chance of generating financial value equivalent to 10 million yen (safe worker) or job applicant B who has an even chance of generating value equivalent to 20 million or zero yen (risky worker), around 80% of US MBA students would choose applicant B, the riskier choice. However, around 80% of Japanese students would choose applicant A, a safer choice. What is the reason for this difference?

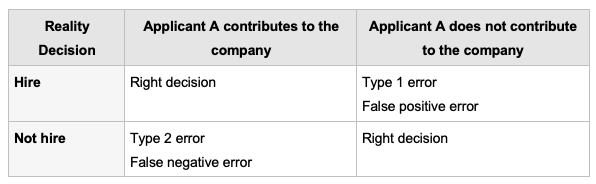

Let us look at Table 2 in order to systematically examine the difference. The decision-making matrix contains two right decision possibilities and two wrong decision possibilities. In the case of deciding whether or not to hire a job applicant, the applicant may be either able or unable to make positive contributions to the prospective employer's business performance, and the prospective employer cannot know for sure which of the two possibilities is right. In this case, the right decision is (1) to hire the applicant if he/she is able to make positive contributions and (2) not to hire the applicant if he/she is unable to do so. The wrong decision is (1) to hire the applicant if he/she is unable to make positive contributions (a Type 1, or ‘false positive’, error) and (2) not to hire the applicant if he/she is able to do so (a Type 2, or ‘false negative’, error).

Table 2 Two wrong decision possibilities regarding hiring

Japanese companies prefer safe workers because they want to minimise the risk of making a false positive error. Underlying this tendency is the lifetime employment arrangement, which is pervasive in Japan and makes it difficult to fire workers once they have been employed, even if the worker makes no contribution to the company. In short, the cost of making a false positive error is high. In contrast, in the US, workers who do not contribute to the company can be fired more easily, so there is a tendency to place more emphasis on applicants' potential rather than on qualities like stability. Another reason is that, unlike US companies, where front-office managers typically have the authority in hiring decisions, Japanese companies give the human resources department centralised authority over hiring. When front-office managers have found hired workers to be useless, they blame the human resources department for making the wrong hiring decision. To avoid the blame, the human resources department makes conservative hiring decisions.

However, the cost of making a false negative error is steadily rising, amid the growing perception that there is a shortage of capable young workers due to the low birth rate and because the value of risky workers is increasing due to changing business characteristics.

Factors aggravating the problem

Even if companies plan to hire workers with diverse profiles or workers with higher potential for innovation, it is difficult to implement hiring according to the plan in many cases. One of the reasons is the use of the multi-stage interview system used in Japan, typically consisting of three to four stages for large corporations. In order to narrow down the long list of applicants, companies use this system, under which only applicants who have successfully passed several interviews are hired. The problem is that, typically, one or at most two interviewers handle each applicant in each stage, and thus a single person could prevent a particular candidate from being hired. Therefore, personal biases of the interviewers can have significant consequences on the types of workers who receive job offers (Sah and Stiglitz 1986).

There is a psychological tendency for humans to be biased or lack objectivity in evaluating other people (Hoffman et al. 2018). Let us assume that a company interviews an applicant with unique characteristics. In Japan, workers who stand out tend to be the source of personality conflicts that distract other workers from the main mission of the office. The multi-stage interview system is highly likely to eliminate applicants with unique profiles and to favour reliable applicants, who are viewed favourably by many interviewers but are typical of the company.

To change this status quo, it is essential to reorganise the interview stage into a process whereby a team of interviewers screen applicants based on a structured interview. This approach should increase the involvement of front-office personnel as well as the diversity in recruitment channels and screening criteria.

Another problem is the use of aptitude tests. As it has become possible for employers to utilise online aptitude tests at low cost, many companies use these tests to narrow down the pool of applicants. However, when many companies use ready-made aptitude tests from a limited number of vendors in order to narrow down the pool of applicants, undesirable consequences could follow. For example, applicants tend to be divided into two groups: people who consistently succeed in advancing to the interview stage and people who are consistently eliminated before the interview stage. This presents a new statistical discrimination problem, in which applicants whose predicted achievement levels are low are not allowed to move on to the interview stage.

This might still be a necessary evil if aptitude tests were effective predictors of future performance. This may not be the case, however. In the data science workshop for human resource managers the author organises, we asked the participants to analyse which applicants actually received job offers (including those who decline the offer) at the end of the interview process. They calculated how much of the difference in the probability of receiving a job offer between successful and unsuccessful applicants, including those that failed in the initial test screening, can be explained by the differences in test scores on the aptitude tests. According to the analyses, no economically significant difference was explained by the aptitude tests. Not only is the accuracy of aptitude tests not very high in predicting which candidates will receive final job offers, but online tests also pose other risks, such as the possibility that applicants may ask other people to take the test on their behalf or that they may not answer questions truthfully.

The presence of these problems does not necessarily mean that companies should not use aptitude tests. For large companies which handle a huge pool of applicants, it is inevitable to narrow down the pool somewhat through paper-screening. Nevertheless, it is important to customise screening test measures to account for the kind of skills and qualities required from workers, instead of only using ready-made indicators prepared by vendors. Ideally, companies should design multiple such measures to attract diverse skills.

Conclusion

As has been made clear above, many companies appear to be adopting flawed recruiting methods while complaining about a shortage of workers. It is essential to take necessary steps, including ensuring that the hiring policy is understood and followed by the recruiting team, making selection based on a team approach and through structured interview, and developing unique measures for initial screening based on aptitude tests and other information on the application form.

Editors’ note: This column first appeared on the RIETI website. Reproduced with permission.

References

Baron, J N and D M Kreps (1999), Strategic human resources: Frameworks for general managers, New York: Wiley.

Hoffman, M, L Kahn and D Li (2018), “Discretion in Hiring”, Quarterly Journal of Economics 133(2): 701-764.

Lazear, E P (1998), “Hiring risky workers”, In Ohashi I and Tachibanaki T (eds) Internal labour markets, incentives and employment, London: Palgrave Macmillan.

Sah, R K and J E Stiglitz (1986), “The architecture of economic systems: Hierarchies and polyarchies”, American Economic Review 76(4): 716-727.