On 9 November 2022, the European Commission adopted a Communication on orientations for a reform of the EU economic governance framework (European Commission 2022). This proposal aims to address the main shortcomings of the current framework, taking into account the economic and social challenges of this decade, as made even more evident and pressing by the pandemic, the Russian war of aggression against Ukraine, and the ensuing energy crisis. The heart of the new framework is a revamped set of fiscal rules reforming the Stability and Growth Pact (SGP).

Since the Commission launched the review of the economic governance in February 2020, there has been a lively debate on the main shortcomings of the current framework and on how to address them. The following issues have been consistently identified by a wide range of stakeholders as the main challenges that a revamped framework should tackle:

- Very high public debt-to-GDP ratios. The financial and sovereign debt crises led to a significant increase in debt ratios, which then started to decline somewhat as of 2015 but with less progress where this was most needed. In 2020, the pandemic hit Member States harshly and asymmetrically, increasing debt levels as well as the heterogeneity in their fiscal and macroeconomic positions. With very high debt-to-GDP ratios and low economic growth, the debt reduction benchmark has not proved to be realistic, as also acknowledged in the German position paper and no debt-based excessive deficit procedure has ever been launched. To tackle high public debt, several contributors to the debate have called for greater differentiation in debt reduction trajectories to ensure gradual, realistic and steady adjustment paths (European Fiscal Board 2020, Martin et al. 2021).

- Limited incentives for investment and reforms to tackle today and tomorrow’s challenges. Pre-existing reforms and investment needs for an inclusive green and digital transition have been made even more pressing by the recent crises. At the same time, the war has also raised the importance of energy security as well as of common defence policy. Overall, the importance of a framework that puts sustainability and growth at par has been increasingly acknowledged, whereby fiscal plans should be designed in a way that is coherent with and facilitate growth and the achievement of common EU priorities (Bénassy-Quéré 2022, Darvas and Wolff 2022, D’Amico et al. 2022). Calls have also been made for a stronger EU budget or a central capacity for the provision of common EU public goods (EFB 2020, Buti and Messori 2022, Buti and Papacostantinou 2022).

- Pro-cyclical bias of fiscal policy. The failure to build fiscal buffers in good times resulted in pro-cyclical fiscal tightening in bad times, leaving to monetary policy the burden of macroeconomic stabilisation. To overcome the pro-cyclical bias of fiscal policy, relying on a medium-term approach and on spending rules as operational indicator has been suggested (European Fiscal Board 2019, Harontunian et al. 2022). Many have also called for a central fiscal capacity that can act as a stabilisation tool (IMF 2022, OECD 2021, ECB 2021).

- Complexity of the EU framework. Past revisions of the framework and the evolution of its interpretation have made the rules complex. Therefore, there has been a broad consensus on the need to simply the framework and improve the transparency of its implementation, with one of the boldest proposals being that by Blanchard et al. (2021) to move from rules to standards. Some have suggested focusing on the most pressing cases with less intrusion where overall risks are low (Beetsma et al. 2022), and to centre the framework around a debt anchor (Weder di Mauro et al. 2018, IMF 2022 Hauptmeier and Kamps 2020).

- Lack of ownership and low enforcement. The track record of compliance and enforcement, in particular of the preventive arm, points – among other things – to the lack of national ownership of EU fiscal rules and low enforcement. A strong role for national medium-term plans compounded with credible annual surveillance and strengthened enforcement at the EU level has been proposed also as a way forward, as in the joint paper by Spain and the Netherlands, as well as greater decentralisation (Wyplosz et al. 2019).

The Commission’s orientation for a reformed economic governance framework aims to set the right incentives for Member States to take full ownership for investing in the green and digital transition and safeguarding their fiscal sustainability. Both are fundamental challenges that will determine Europe’s economic prospects for decades ahead. Neither of them can be delayed. Public financing of the twin transition cannot be put on the backburner until public debt has been brought down to safer levels. Credible strategies for consolidating public finances are indispensable, providing investors with the reassurance that public debt is sustainable and allowing market funding to be raised for public investment.

While a revised surveillance framework as proposed in the Commission’s communication is a pressing priority, it is not the only elements in completing EMU’s architecture. Full Banking Union and Capital Market Union are needed to reduce financial vulnerabilities, enhance shock absorption, and improve the allocation of factors of production. As stressed by the ECB, the IMF, and the OECD during the public consultation on the economic governance review, a permanent central fiscal capacity aimed at providing European public goods and improving the macroeconomic stabilisation remains a missing element of EMU.

The SGP trilemma

The EU is in the midst of the latest of three large economic shocks in a decade: the sovereign debt crisis, which was ended by the “whatever it takes” speech by Mario Draghi in July 2012; the pandemic crisis, which forced the EU to cross the red line of common borrowing with NextGenerationEU in the summer of 2020; and now the energy crisis as a result of Putin’s war of aggression. The sovereign debt crisis led to a considerable flexibilisation of the common fiscal rules which were de facto set aside by the triggering of the general escape clause (GEC) in March 2020.

The reform of the fiscal rules should allow to move towards a simpler and more efficient surveillance system when the lifting of the GEC will take place which is expected to occur in the course of 2023.

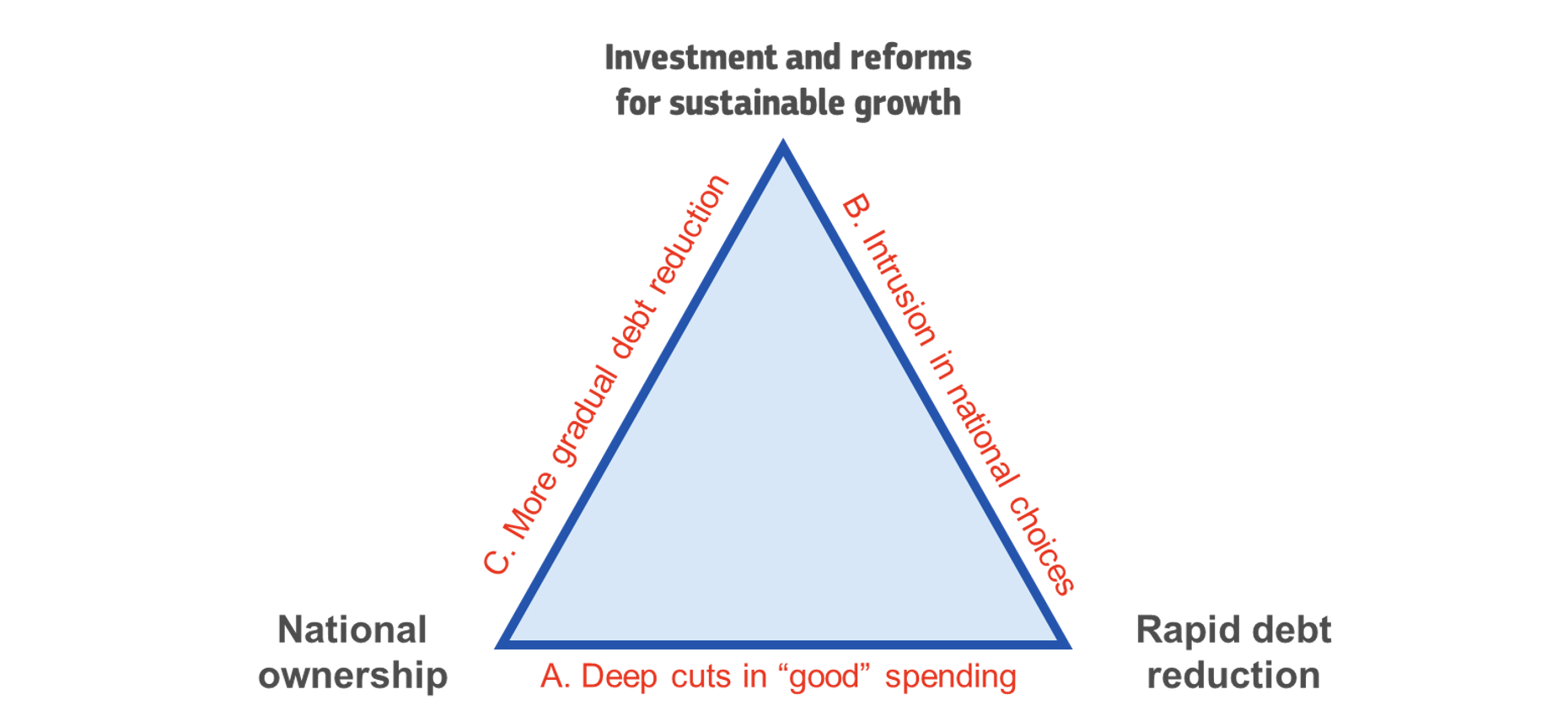

The experience of the first two decades of EU points to what one may call the ‘SGP trilemma’: one cannot purse at the same time a rapid reduction in the public debt ratio, improve the quality of public finances to reflect common EU priorities and the commitment to ‘build back better’, and maintain strong ownership and national political stability (see Figure 1).

Figure 1 The economic governance trilemma

Source: Authors’ elaboration.

A rapid decrease in public debt and an improvement in fiscal composition is likely to come into conflict with the objective of maintaining national political stability (solution A). An attempt to achieve both objectives at the same time was made in the context of the rescue programmes during the global financial crisis. However, that required heavy intrusion by the Commission, the EU, and the IMF, which came into conflict with the goal of national financial stability.

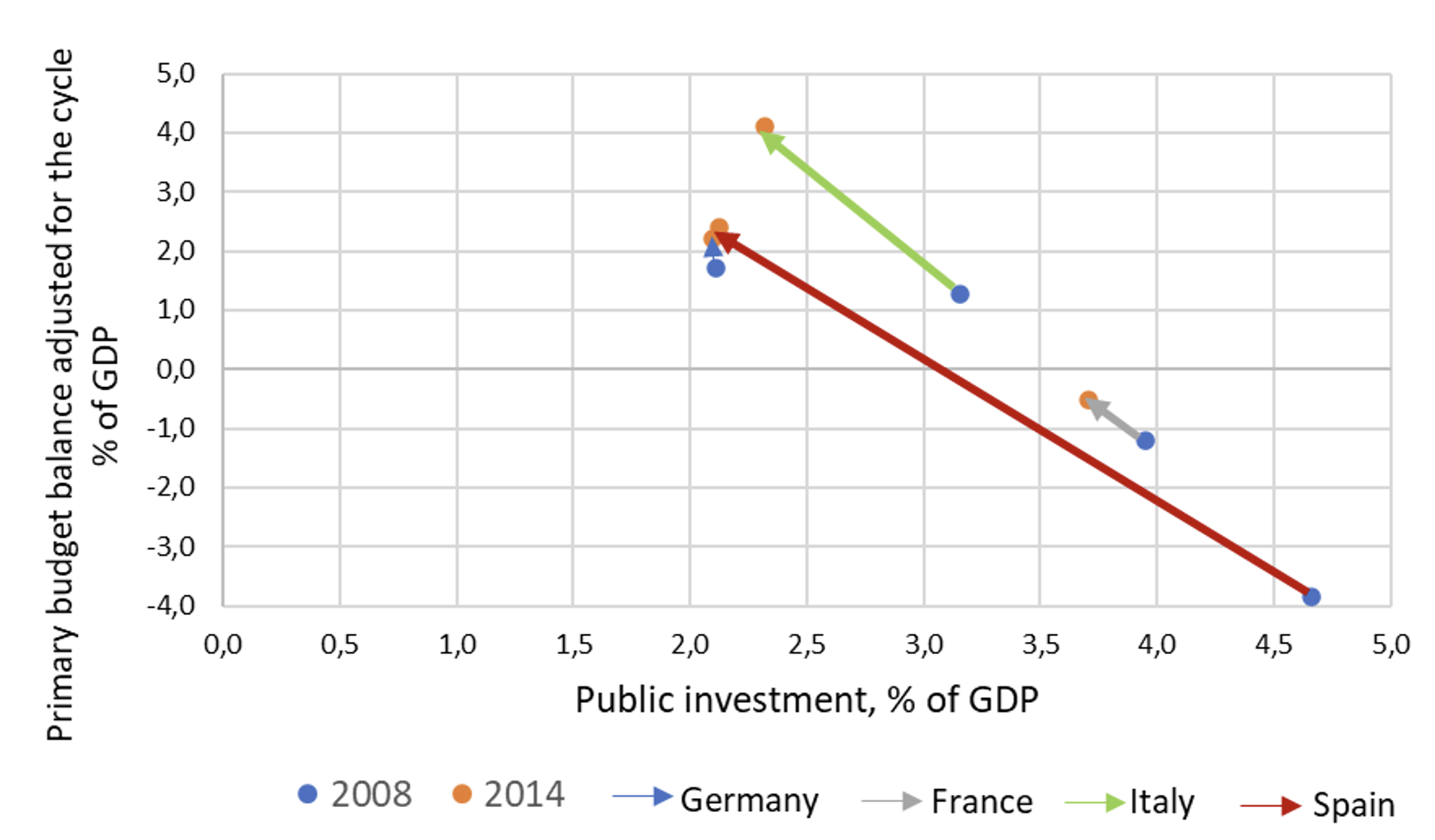

As the experience shows, a swift debt reduction in the context of strong ownership and stable national political conditions would most likely imply cuts in good spending that are usually supported by weaker constituencies (solution B). Empirical evidence shows that market pressure may result in large fiscal retrenchments, but at the cost of a deterioration of the quality of public finances which had adverse effects on potential growth and sustainability down the line (see Figure 2).

Figure 2 Fiscal position and public investment

Source: European Commission

The only solution of the trilemma that ensures an improvement of the quality of public finances and strong political ownership is C, which accepts a more gradual curbing of the public debt ratio. A lower ‘gradient’ allows national policymakers to achieve the necessary fiscal retrenchment without recourse to blind austerity and preserving the enhancement of public investment. Solution C entails a more gradual pace of debt reduction than prescribed by the current SGP. This is justified by the fact that the pace of debt reduction implied by the current debt rule would be economically suboptimal and politically unrealistic. A more realistic requirement anchored in a clear medium-term fiscal-structural strategy would lead to a gain in credibility. Moreover, while Member States would enjoy more flexibility on their debt reduction paths (more ownership), they would be held more accountable for their actual delivery through scrutiny and stronger enforcement. Solution C is also superior in terms of averting the risk of sacrificing the most-needed public spending on the altar of rapid debt reduction (solution A) and the risk of unduly meddling in the national responsibility for budgetary and reform policies (solution B), which would be questionable with respect to democratic legitimacy.

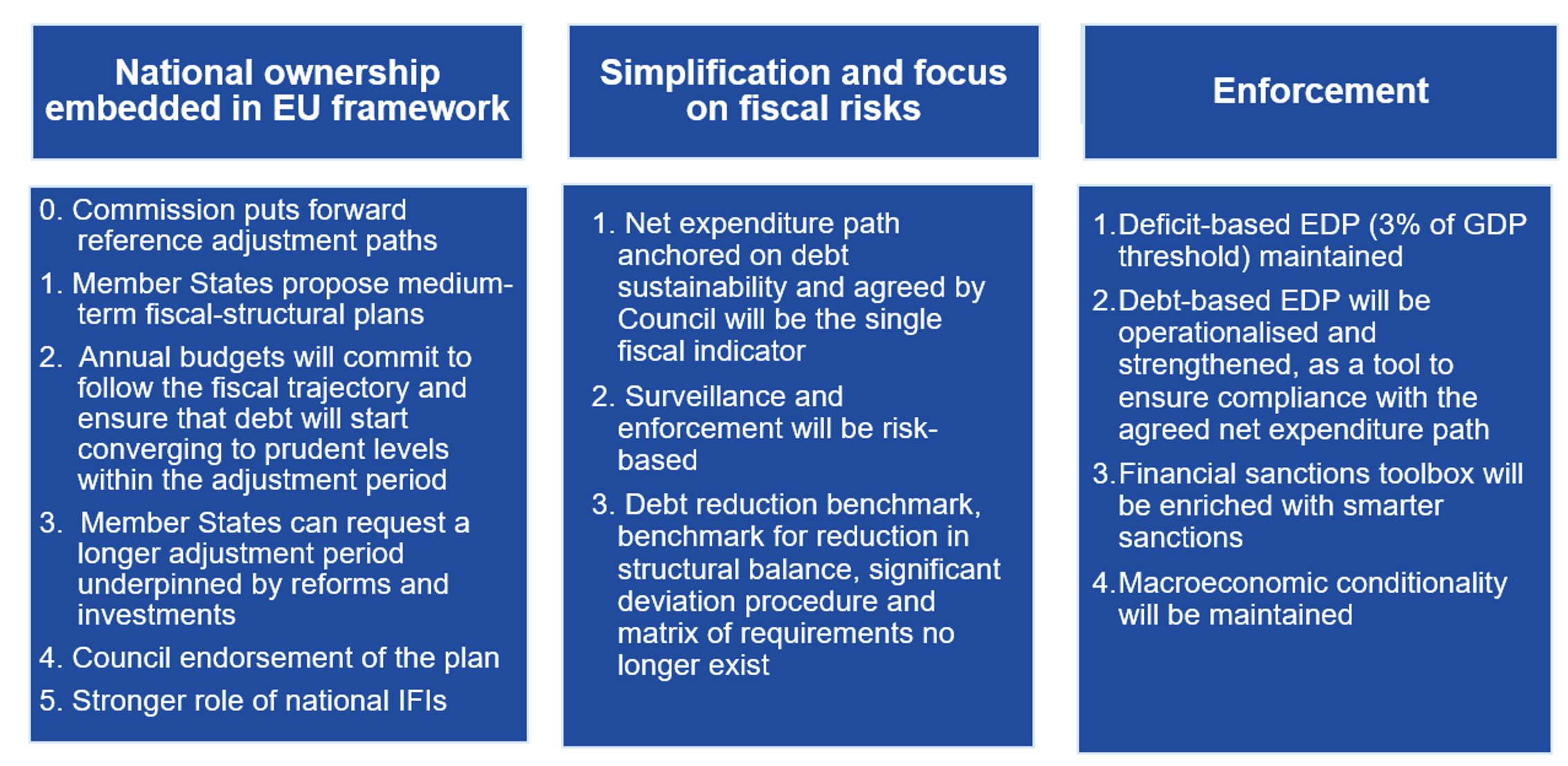

A set of EU fiscal rules fit for the next decade

Stronger national ownership over medium-term fiscal-structural plans that bring together fiscal, reform and investment policies, within a common EU framework, is the cornerstone of the proposed framework. The revised framework (see Figure 3) will set a requirement ensuring that debt is put on a downward path or stays at prudent levels, and budget deficit remains below 3% of GDP over time. Following a dialogue with the Commission about its medium-term policy plans, the Member State would present a four-year plan with a fiscal trajectory and priority public investment and reform commitments that together ensure sustained debt reduction and sustainable growth. Member States will be required to respond to the European Semester country-specific recommendations and should put forward initiatives that are in line with EU strategic priorities. Independent national fiscal institutions would play a role in setting the assumptions underlying the plan, providing an assessment with respect to debt sustainability and medium-term goals, and monitoring compliance.

Figure 3 A suggested new fiscal framework

Source: European Commission (2022).

Member States can propose reforms and investment commitments that underpin a more gradual adjustment path. The option to extend the adjustment period by up to three years reflects that there is no trade-off between fiscal adjustment and reforms and investment, since they both help bringing debt down in a sustained way. Moreover, as past experience shows, some Member States have been running primary surpluses over many years without succeeding in bringing down debt levels. The adjustment path, the reforms, and investments will be discussed with the Commission and, once agreed, will be adopted by the Council. The plans would be committed to via national budgets, with the possibility for the Member State to revise the plan after a minimum period of four years. In case of objective circumstances that make the original timetable unfeasible, an earlier revision could be agreed.

An ambitious simplification of the Stability and Growth Pact is proposed. To improve effectiveness and transparency, a single operational indicator anchored on debt sustainability would serve to set the fiscal trajectory. We propose to use net primary expenditure as the single indicator, i.e. expenditure net of discretionary revenue measures and excluding interest expenditure as well as cyclical unemployment expenditure, which would ensure a higher degree of macroeconomic stabilisation. This simplification would increase transparency, including among policymakers, and would allow to do away with a number of fiscal surveillance tools that are overly complex, rely on unobservable indicators, or have not stood the test of time. While annual fiscal surveillance at the EU level would be conducted solely on the basis of the expenditure path, Member States could translate net primary expenditure into alternative indicators for national budgetary purposes (e.g. a structural balance).

It is proposed to move to a more risk-based approach focused on preventing gross fiscal policy errors. The existing framework requires all Member States to make broadly similar adjustment efforts, regardless of their actual fiscal position and the debt sustainability risks they face. However, debt levels and projected debt dynamics differ widely across Member States, even more so after the pandemic. Within a common EU framework, the Commission would therefore use its debt sustainability analysis framework – a well-established toolkit for assessing debt sustainability risks – as a common risk-assessment tool that would inform the design of the plan. Concretely, the tool would help to differentiate between Member States according to their public debt challenge, cast light on the drivers of their debt dynamics and result in the Commission making public a reference expenditure path that can serve as a compass to the Member State’s plan.

More scope for Member States to design their fiscal trajectories would go hand-in-hand with a more stringent enforcement. The excessive deficit procedure (EDP) would remain unchanged for breaches of the 3% of GDP deficit reference value of the Treaty. This is an element of EU fiscal surveillance that has been effective in influencing fiscal behaviour and is well understood by policymakers and the public thanks to its simplicity (Buti and Gaspar 2021). The EDP for breaches of the debt criterion would be strengthened and focus on departures from the agreed expenditure path that the Member State has committed itself to. A notional control account would help to monitor deviations from the expenditure path over time. Departures from the expenditure path would for high-debt Member States by default lead to the opening of an EDP. In case of non-implementation of the reforms and investment underpinning a more gradual adjustment path, the agreed adjustment path would become more restrictive.

The range of sanctions would be broadened, by adding smarter and more targeted measures. The possibility of financial sanctions would be kept as a deterrent, but the modalities for their deployment should be broadened. In addition to the existing financial sanctions, smarter sanctions with lower amounts would be envisaged. This would put more focus on reputational costs, which could also be further enhanced, for example through ministers of Member States in EDP being required to present in the European Parliament the measures to correct the situation.

Conclusions

The criteria for success for a governance framework fit for the future are therefore to allow for strategic public investment and to put public debt ratios on a sustained and credible downwards path. Prudent fiscal strategies are indispensable to achieve this, requiring a gradual fiscal consolidation and an improved composition of public expenditure to turn around debt dynamics and create space for investment. Growth-enhancing public investments must remain top of the agenda, since they are required to steer and speed up the twin transition and will facilitate private sector investment (European Commission 2020). Maintaining reform momentum is needed too for a number of reasons, helping for instance to strengthen the resilience and growth potential that support fiscal sustainability, remove investment barriers that hamper the green and digital transitions and improve expenditure control in order to free up public funds for investment.

Authors’ note: The authors write in their personal capacity.

References

Beetsma, R, M Bordignon, X Debrun, M Szczurek, N Thygesenet (2022), “Making the EU and national budgetary frameworks work together”, VoxEU.org, 13 September.

Bénassy-Quéré, A (2022), “How to ensure that European fiscal rules meet investment”, VoxEU.org, 6 May.

Blanchard, O J, A Leandro, and J Zettelmeyer (2020), “Redesigning the EU Fiscal Rules: From Rules to Standards”, PIIE Working Paper 21-1

Buti, M, M Messori (2022), “A Central Fiscal Capacity in the EU Policy Mix”, CEPR Discussion , Paper, 17 October

Buti, M, G Papaconstantinou (2022), “European public goods: How we can supply more”, VoxEU.org, 31 January.

Buti, M and V Gaspar (2021), “Maastricht values”, VoxEU.org, 8 July.

D'Amico, L, F Giavazzi, V Guerrieri, G Lorenzoni, C-H Weymuller (2022), “Revising the European fiscal framework, part 1: Rules”, VoxEU.org, 14 January.

Darvas, Z, G B Wolff (2022), “How to reconcile increased green public investment needs with fiscal consolidation”, VoxEU.org, 7 March.

ECB (2021), “Monetary-fiscal policy interactions in the euro area”, Occasional Paper Series No 273, September

European Commission (2020), Europe's moment: Repair and Prepare for the Next Generation, COM(2020) 456 final

European Commission (2022), Communication on orientations for a reform of the EU economic governance framework, COM (2022) 583 final

European Fiscal Board (2019), “Assessment of EU fiscal rules, with a focus on the six and two-pack legislation”, August

European Fiscal Board (2020), Annual Report.

Haroutunian, S, S Hauptmeier, N Leiner-Killinger, P Mergenthaler (2022), “A central bank view of reforming Europe’s fiscal framework”, VoxEU.org, 13 May.

Hauptmeier, S, C Kamps, (2020), “Debt rule design in theory and practice: the SGP’s debt benchmark revisited”, ECB Working Paper Series No 2379.

Martin, P, J Pisani-Ferry, and X Ragot (2021), “Reforming the European Fiscal Framework”, Conseil d’Analyse Economique, 63, April.

Nathaniel, G A, R Balakrishnan, B B Barkbu, H R Davoodi, A Lagerborg, W R Lam, P A Medas, J Otten, L Rabier, C Roehler, A Shahmoradi, M Spector, S Weber, J Zettelmeyer (2022), “Reforming the EU Fiscal Framework: Strengthening the Fiscal Rules and Institutions”, IMF Departmental Papers, 5 September

OECD (2021), “OECD Economic Survey of Euro Area”, September

Weder di Mauro, B, J Zettelmeyer, H Rey, N Véron, P Martin, F Pisani, C Fuest, P Gourinchas, M Fratzscher, E Farhi, H Enderlein, M Brunnermeier and A Bénassy-Quéré, (2018), “Reconciling risk sharing with market discipline: A constructive approach to euro area reform”, CEPR Policy Insight No. 91.

Wyplosz, C (2019), “Fiscal rules for Europe – Fiscal Discipline in the Eurozone: Don’t Fix It, Change It”, IFO DICE Report, Summer Vol 17