Can social media affect election outcomes? A popular narrative holds that, in 2016, Twitter played a decisive role in both the presidential election in the US and the UK’s Brexit referendum. Both Hillary Clinton and Donald Trump have argued that these factors were instrumental in the 2016 election outcome, as has Barack Obama (The New Yorker 2016). As Brad Parscale, Trump's digital media director in 2016, put it: “Facebook and Twitter were the reason we won this thing. Twitter for Mr. Trump. And Facebook for fundraising” (Wired 2016). In a recent interview with CBS News’ 60 Minutes, Trump himself declared: “I think I wouldn’t be here if I didn’t have social media.”

Many see these statements as evidence of social media's broader influence on political polarisation and the recent re-emergence of right-wing populist politicians in many countries. US Federal Election Commissioner Ellen Weintraub, for example, has argued that social media “has no idea how seriously it is hurting democracy” (NPR 2020). An alternative view holds that social media platforms are biased against conservative voices (e.g. Wall Street Journal 2020). In the 2016 presidential election, Trump notably received fewer votes from demographic groups with higher propensity to use social media or the internet (Boxell et al. 2018). Indeed, Trump's broadest support came from older white voters without a college education in rural areas, who are among the least likely people to use social media actively (Hargittai 2015). Further, the content on social media platforms – particularly on Twitter – is disproportionately left-leaning. The Pew Research Center estimates that in 2018, 60% of Twitter users identified as Democrat and only 35% as Republican, and 80% of Twitter users strongly disapproved of President Trump (Pew 2019a, 2019b).

Existing research hence provides an incomplete picture. In recent work (Fujiwara et al. 2020), we shed light on Twitter’s impact on US federal elections. Specifically, we estimate the causal effect of Twitter’s popularity in a county (measured by the number of users) by exploiting variation in early Twitter adoption caused by the 2007 South by Southwest festival (SXSW).

The 2007 South by Southwest festival and the rise of Twitter

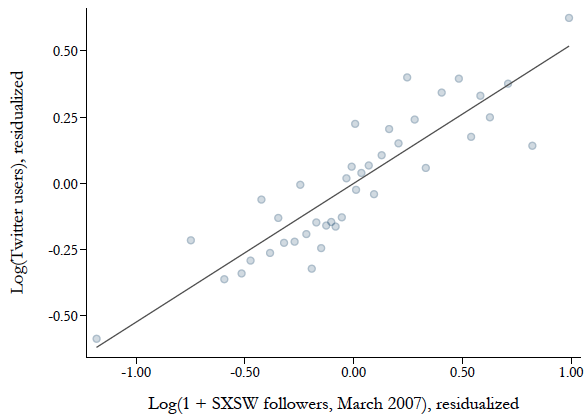

After its launch in March 2006, Twitter’s popularity grew slowly, until an advertising campaign at SXSW in March 2007 quadrupled the platform’s growth rate. Because network effects are key for social media, the SXSW festival influenced the geography of Twitter usage in the US by boosting adoption in the home counties of SXSW attendees (Müller and Schwarz 2019). The resulting differences in Twitter usage persist until today. Figure 1 shows the strong positive correlation between the number of SXSW followers from March 2007 in a county and the number of Twitter users in county as of 2015 (in logs).

We leverage the fact that this initial shock to Twitter adoption, conditional on geographic and socioeconomic controls and previous interest in SXSW on Twitter, is essentially uncorrelated with a host of county characteristics, as well as both levels and trends in election outcomes before Twitter's launch.

Figure 1 The SXSW festival and Twitter usage

The electoral effects of Twitter

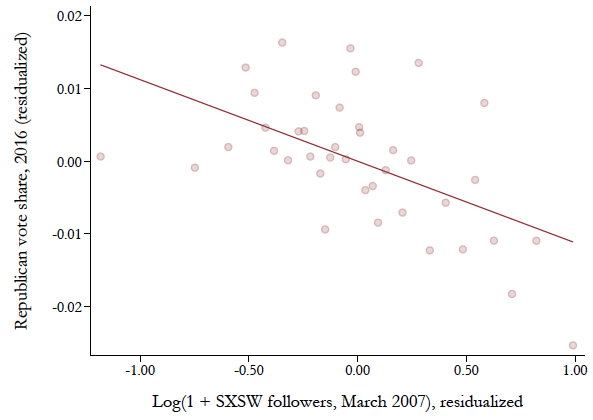

Based on the variation in Twitter usage created by the SXSW festival, we find that a 10% increase in a county's number of Twitter users lowers the vote share of Republican presidential candidate Trump by 0.2 percentage points. The resulting relationship is show in Figure 2. The implied persuasion rate is around 8.6%, which is somewhat smaller than the estimated pro-Republican effect of Fox News (DellaVigna and Kaplan 2007, Martin and Yurukoglu 2017). Investigating individual-level voting decisions using the Cooperative Congressional Election Study (CCES), we find that that changes in the Republican vote share appear to be driven by independents and moderates changing their voting decision in favour of the Democratic candidate (Clinton).

Figure 2 SXSW festival and 2016 Republican vote share

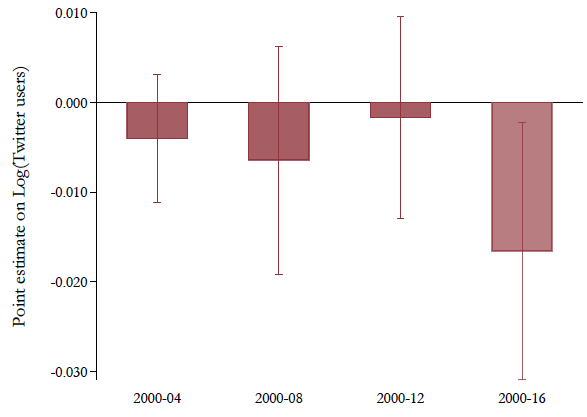

Importantly, we find no effect of Twitter in earlier presidential elections, including the period before Twitter’s launch in 2006 (see Figure 3). The coefficients before 2016 are far smaller and indistinguishable from zero. This also holds for the 2012 elections, when Twitter already had a significant user base.

Figure 3 Effect on earlier presidential elections

What was special about the 2016 election?

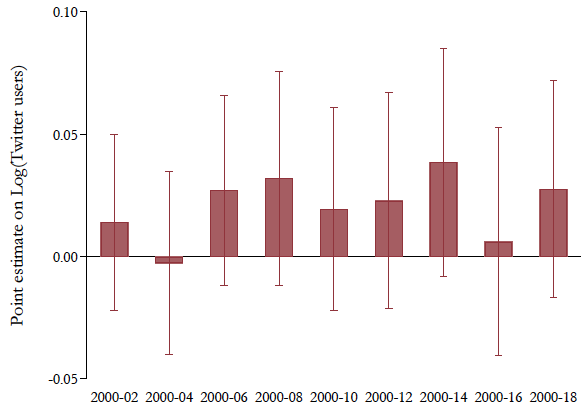

So why does it appear that Twitter only affected the 2016 presidential election? Trump’s role as an outsider candidate may have played a particular role. As can be seen in Figure 4, we find no negative effect on Republican vote shares in House elections, including in 2016. (The same pattern also holds for Senate elections.) This means that people on the same day decided to vote against Trump but not against the Republican Party in general.

Approval data for Republican and Democratic presidential candidates during the primaries also suggests that Twitter changed voters’ minds about particularly right-wing candidates rather than about Republicans in general. People in counties with higher Twitter usage had less favourable views of the relatively far-right candidates Donald Trump and Ted Cruz, while we find no such link for the more moderate Republicans John Kasich and Marco Rubio. At the other end of the political spectrum, it is again Hillary Clinton who profited the most from higher Twitter usage.

These results suggest that Twitter’s particular role in 2016 was not because of higher user numbers or a general pro-Democratic shift in the platform’s content. Rather, they are consistent with Trump’s inflammatory campaign triggering a backlash on Twitter that had effects on voter choices.

Figure 4 Effect of Twitter on House elections

We provide additional support for this hypothesis by analysing the content of 130 million election-related tweets sent during the 2012 and the 2016 presidential campaigns. Specifically, we analyse the partisan slant of political content on Twitter by asking how ‘similar’ tweets about the presidential candidates (Obama, Romney, Clinton, Trump) ‘sound’ relative to tweets sent by Democratic or Republican Congresspeople, similar to the approach of Gentzkow and Shapiro (2010).

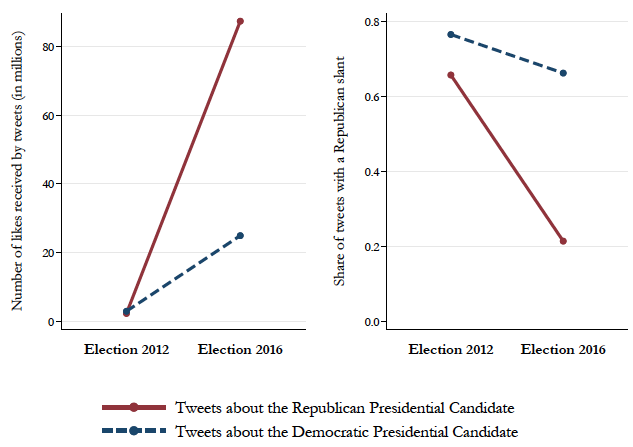

We use the tweets from Republican and Democratic congress members to train a machine learning classifier that predicts whether a tweet is more likely to approve or disapprove of the candidate. The left panel of Figure 5 shows that, in the 2012 election, tweets about both presidential candidates received a similar number of likes, with slightly more likes for tweets about Obama. In 2016, the overall volume of political Twitter content increased ten-fold and we observe four times more Twitter content about Trump relative to Clinton.

More importantly, the right panel shows a drastic shift in the slant of election-related Twitter content. In the 2012 election, close to 70% of the tweets about Romney exhibited a Republican slant. In 2016, around 80% of the tweets about Trump appear to come from the Democratic side of the political spectrum. Taken together with the far larger amount of Twitter content mentioning Trump, these findings suggest Twitter content had a clearly pro-Democratic slant around the 2016 presidential election.

Figure 5 Slant of election-related Twitter content

Concluding remarks

Overall, a potential interpretation of these results is as follows. Twitter (and other social media platform) users are more likely to be young, more educated, live in urban areas, and support the Democratic party. This pro-Democrat slant did not manifest itself in a pronounced fashion before the 2016 presidential election because the Republican candidates were relatively moderate. In 2016, however, Twitter became a vehicle for spreading criticism of Trump. The sheer volume of this slanted content may have persuaded voters with weaker priors – independents and perhaps more moderate Republicans – to vote against Trump in the presidential election.

It is important to highlight some caveats of our findings. First, they are silent on the effect of social media platforms other than Twitter, such as Facebook, because we use a source of variation based on a ‘shock’ that is specific to Twitter. Second, our research design cannot speak to the effect of particular types of social media content on Twitter, such as the potential role of foreign governments or misinformation (‘fake news’). Nevertheless, the results suggest that Twitter can, indeed, affect election outcomes.

References

Allcott, H and M Gentzkow (2017), “Social Media and Fake News in the 2016 Election”, Journal of Economic Perspectives 31(2): 211-36.

Autor, D, D Dorn, G Hanson, K Majlesi et al. (2020), “Importing political polarization? the electoral consequences of rising trade exposure”, American Economic Review 110(10): 3139-83.

Barbera, P (2014), “How Social Media Reduces Mass Political Polarization. Evidence from Germany, Spain, and the US”.

Boxell, L, M Gentzkow and J M Shapiro (2017), “Greater Internet Use Is Not Associated with Faster Growth in Political Polarization Among US Demographic Groups”, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America.

Boxell, L, M Gentzkow and J M Shapiro (2018), “A Note on Internet Use and the 2016 U.S. Presidential Election Outcome”, PLOS ONE 13(7): 1–7.

Enikolopov, R, A Makarin, and M Petrova (2020), “Social Media and Protest Participation: Evidence from Russia”, Econometrica 88(4): 1479-1514.

DellaVigna, S and M Gentzkow (2010), “Persuasion: Empirical Evidence”, Annual Review of Economics 2(1): 643-669.

DellaVigna, S and E Kaplan (2007), “The Fox News Effect: Media Bias and Voting”, The Quarterly Journal of Economics 122(3): 1187-1234

Fujiwara, T, K Müller, and C Schwarz (2020), “The Effect of Social Media on Elections: Evidence from the United States”, Working Paper.

Gentzkow, M and J M Shapiro (2010), “What Drives Media Slant? Evidence from US Daily Newspapers”, Econometrica 78(1): 35-71.

Hargittai, E (2015), “Is Bigger Always Better? Potential Biases of Big Data Derived from Social Network Sites”, The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 659: 63–76

Martin, G J and A Yurukoglu (2017), “Bias in Cable News: Persuasion and Polarization”, American Economic Review 107(9): 2565–2599.

Müller, K and C Schwarz (2019), “From Hashtag to Hate Crime: Twitter and Anti-Minority Sentiment”, Working Paper.

NPR (2020), “Facebook Clamps Down On Posts, Ads That Could Undermine U.S. Presidential Election”,

Pew Research Center (2019b), National Politics on Twitter: Small Share of U.S. Adults Produce Majority of Tweets, Technical report.

The New Yorker (2016), “Obama Reckons with a Trump Presidency”.

Wall Street Journal (2020), “Twitter’s Partisan Censors”.

Wired (2016), “Here’s How Facebook Actually Won Trump the Presidency”.