This week’s European Parliament election (22–25 May) has several unprecedented features. Most importantly, the main pan-European parties are fielding lead candidates for European Commission President. Turning the election into a presidential horse race was intended to increase electoral participation and enhance the Parliament’s democratic legitimacy, even though it remains to be seen whether voters will actually see things this way.

Critics often blame European citizens’ relative lack of interest in the European Parliament on its inherent inequality of representation. Voters in smaller member states are overrepresented. Germany’s Federal Constitutional Court, when ruling on the Lisbon Treaty on 30 June 2009, said that the European Parliamentary election process ‘does not take due account of equality’. In the Court’s view, this constitutes one of two key factors in the European Union’s ‘structural democratic deficit’, the other being the European Parliament’s ‘position in the European competence structure’, i.e. its lack of power compared to other EU institutions.1

How unequal is the representation comparatively?

In the Treaty on European Union, government representation in the lower house is based on both a principle of disproportionate electoral weight given to smaller countries, and on binding thresholds of minimum and maximum representation.2 As a consequence, the European Parliament is at the low end in terms of electoral equality.

- One way to measure voter inequality is to look at the ‘voting Gini coefficient’.

- This uses the familiar measure of inequality of income, but applies it to European Parliament voting power per voter.

Members of the European Parliament will be elected by voters in given constituencies. In some nations, constituencies follow a sub-national geographical division; in others, constituencies are allocated a number of seats in the lower house based on population proportion. Regardless of the method, it is possible to assess the number of voters that will be represented by each Member of the European Parliament (MEP).

The voting power per voter is then just the vote share of one MEP (i.e. 1/n, where n is the number of MEPs) divided by the number of voters represented. This indicator varies widely across constituencies, since the number of voters per MEP varies greatly – from under 70,000 voters per MEP to over 700,000 per MEP. This number tends to be higher for the most populous member states.

- Ordering the ‘voting power’ from the lowest vote share to the highest yields a ‘voting Lorenz curve’, and the Gini is calculated as usual.

- A high voting Gini coefficient suggests a high degree of voting power inequality among citizens eligible to vote.

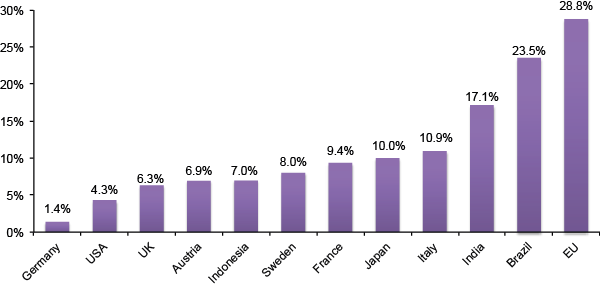

Figure 1 shows the Gini coefficients for the European Parliament (EP) and that of several other parliaments. Voting power in the EP is outside the norm of individual European countries in terms of equality of representation. Germany, whose professed commitment to this principle is unparalleled among countries reviewed, is at the other end of the spectrum. Indeed, the European Parliament is at the low end in terms of electoral equality even beyond Europe.

Figure 1. Voting Gini coefficients

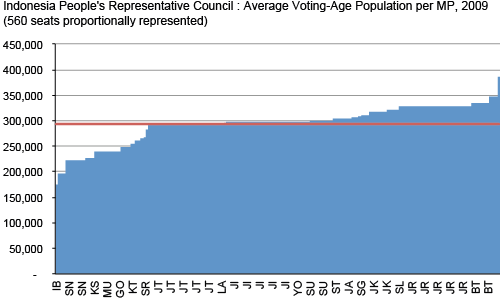

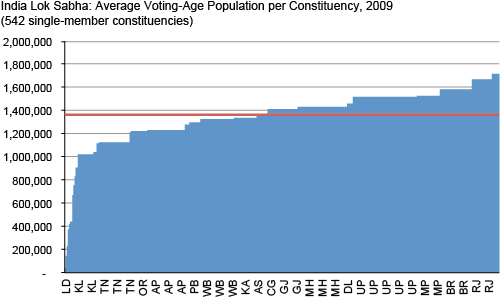

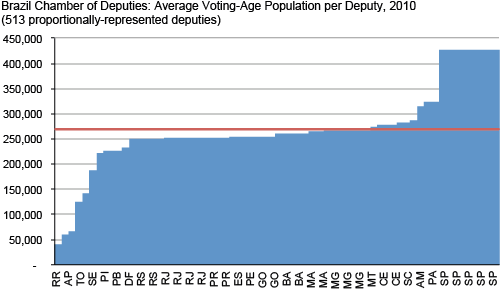

Higher levels of inequality of representation may be expected in larger, more diverse polities where the political complexity of federal arrangements leads to awkward institutional compromises, which is definitely the case of the EU. In our sample, high voting Gini coefficients are indeed also observed for the lower houses in India and Brazil, which come closest to the EP on that measure. For example, in Brazil voters from Sao Paulo state are notoriously underrepresented. Yet the US and Indonesia, which are also large and diverse, both display comparatively low voting Gini coefficients.

How much change would produce an acceptable level of equality of representation?

Read in a different light, Figure 1 suggests that the European Parliament would not need to go all the way to representative equality as high as the German Bundestag to join the norm of lower chambers in democratic polities. This is important, since a modified distribution of seats that reduced the voting Gini coefficient to something like 10% could be achieved without entirely renouncing the Treaty principle of ‘degressive proportionality’ as currently implemented by the European Council. It would, however, require lowering the minimum of six MEP seats per member state, and thus a modification of the Treaty on European Union.

As an illustration, one gets a voting Gini coefficient of 10% with a distribution of seats that is identical to the current one for the six largest member states (Germany, France, UK, Italy, Spain, and Poland), but which halves the number of seats in the four smallest member states (Malta, Luxembourg, Cyprus, and Estonia) from six to three each, and smoothens the distribution with a less sharp reduction in seats numbers for the remaining 18 member states.

Concluding remarks

If such a level were reached, our international comparison suggests that it would no longer be reasonable for the German Federal Constitutional Court or other watchdogs to label the European Parliament’s representative inequality as an element of “structural democratic deficit”. This labelling, however, does not appear unreasonable under the current arrangements.

Appendix

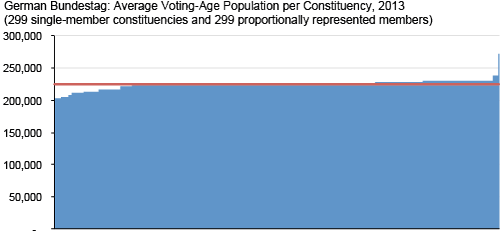

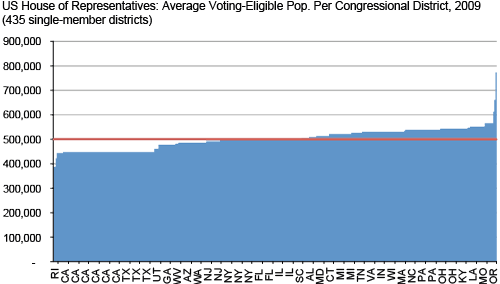

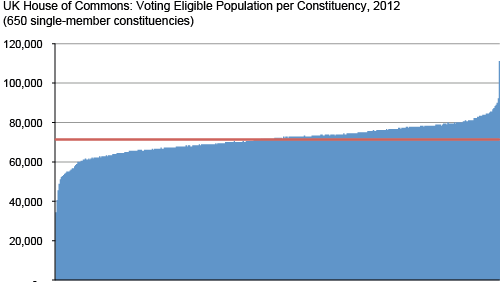

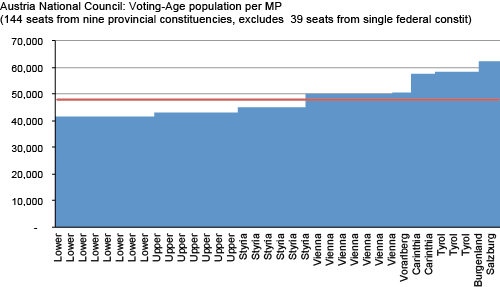

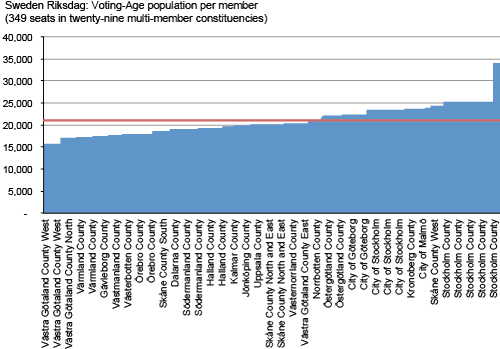

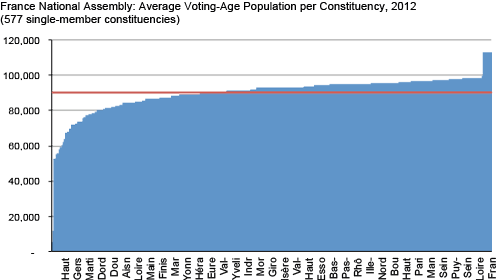

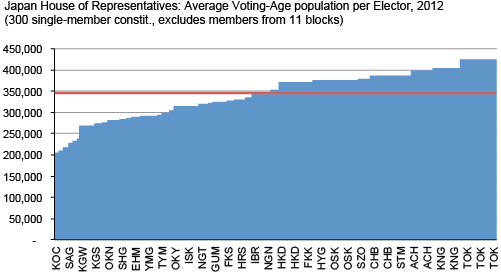

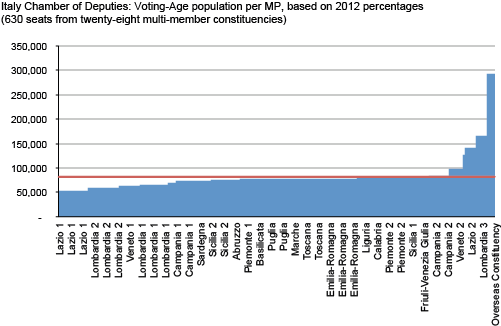

In the charts below, we compare the skewed nature of the European Parliament’s representation of European voters with other lower houses of large or medium-sized democratic polities.

For each chamber, the chart shows the distribution of the number of eligible voters per representative, from the one(s) representing the lowest number of eligible voters, on the left end, to the one(s) representing the most, on the right end. A flat distribution indicates a high level of equality of representation. A sloped or skewed distribution indicates inequality of representation.3

1 The court’s press release in English about its ruling on the Lisbon Treaty is at https://www.bundesverfassungsgericht.de/pressemitteilungen/bvg09-072en.html.

2 The EU Treaties stipulate that ‘Representation of citizens should be degressively proportional, with a minimum threshold of six members [of the European Parliament] per Member State. No Member State shall be allocated more than ninety-six seats’ (Article 14(2) of the Treaty on European Union). The ratio between the maximum and minimum (96/6) is 16 to 1, while the ratio between voting-age populations of the largest and smallest members (Germany and Luxembourg, respectively) is more than 172 to 1. However, no specific formula for representation is provided, and the exact composition is to be adopted by unanimous decision of the European Council. The latest apportionment decision was adopted in June 2013, in the run-up to the accession of Croatia as the EU’s 28th member state.

3 For most countries reviewed, average voting-age population per government representative is based on the total population per relevant territorial subdivision (e.g. state or province), taken from each country’s census bureau, and on the ‘Voting-Age Population’ (VAP) variable from the International Institute for Democracy and Electoral Assistance (IDEA)’s database (http://www.idea.int/).

The charts depict the simple division of voting-age-population per territorial subdivision by the number of representatives in the lower house that serve that particular territorial subdivision. The number of government representatives from each subdivision was found in each country’s lower house website. Voting-age population per subdivision was calculated by multiplying the VAP number by the subdivision’s percentage share of the country’s total population. Percentage shares were calculated based on census data for total population from each country’s statistics bureau. IDEA estimates the VAP number based on data from the International Database of the US Census Bureau. IDEA includes all citizens over the age of 18 within the scope of VAP. However, this figure does not take into account legal barriers, such as registration. It also excludes resident non-citizens from the pool. For the US, we used data from the United States Elections Project at George Mason University (http://elections.gmu.edu/). For the UK we used the total number of parliamentary electors from the UK Office of National Statistics, which they define as “residential qualifiers, attainers and overseas electors”.