‘Smart’, or targeted, sanctions have become a go-to tool of international policy in the last 20 years. In 2019, the US had over 70 countries under such sanctions (Felbermayr et al. 2020). International players opted for sanctions to respond to a growing concern that the comprehensive sanctions may have collateral damage and impose “severe negative humanitarian consequences for the civilian population” (SECO 2017, Swiss Confederation et al. 2001).

However, it is a priori unknown how such sanctions affect the targets, how they work through the economy, and whether they indeed avoid collateral damage (let alone to what extent they are successful). Targeted policies affecting specific firms may have important aggregate implications if they reallocate resources in the economy. What can we learn from the 2014-2020 sanctions episode in Russia about how smart sanctions work? Can we draw insights into how the Russian economy is reacting to stronger sanctions in 2022?

Because of the way targets are chosen, the overall effect of targeted sanctions is ambiguous ex ante. Sanctions may target the inputs of firms that are more productive and important for the economy, in which case these sanctions would hurt both these firms and the aggregate economy. Instead, sanctions may hurt the firms that are politically connected and over-resourced, in which case these sanctions would hurt the firms at an individual level but simultaneously improve the allocation of resources and productivity in the aggregate, purging the economy of unproductive firms. At the same time, the state may protect these sanctioned firms and fully reverse and even overshoot the direct effect of sanctions.

The sanctions imposed by the US after the annexation of Crimea in 2014 pose a natural experiment to study this question. Over 1,000 targets were sanctioned by the US, with treatment varying from blocking some to all input and output transactions, with other countries largely mimicking the US treatment.

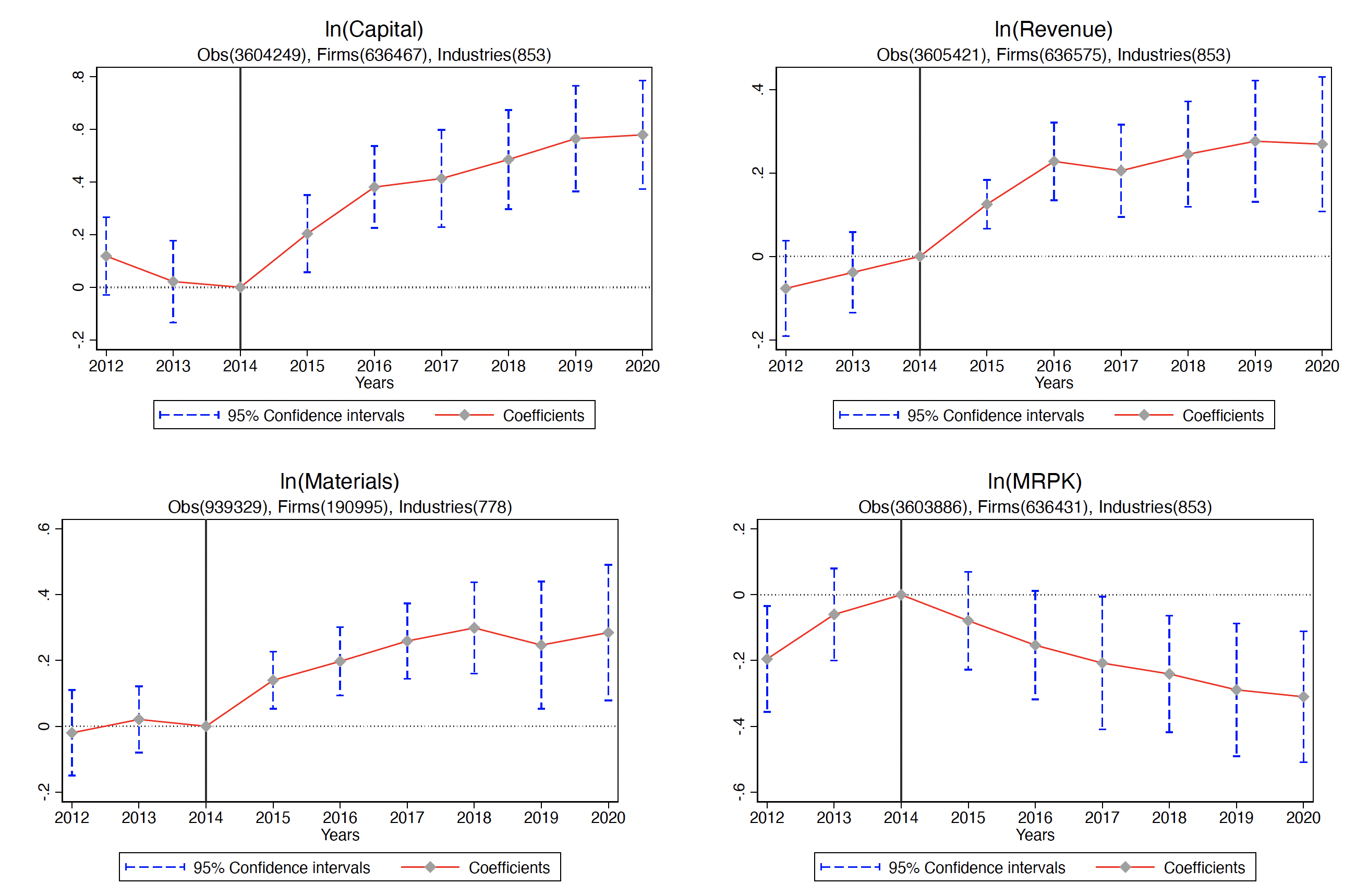

Figure 1 Average effects of sanctions on sanctioned firms relative to non-sanctioned firms, by year, before and after 2014

Notes: Outcome variables are natural logs of ‘Capital’, ‘Revenue’, ‘Materials’ and ‘Marginal Revenue Product of Capital’ (‘MRPK’). Controls for 4-digit industry-by-year fixed effects, firm size-by-year fixed effects, firm fixed effects. Clustering is at the firm and industry-by-year level.

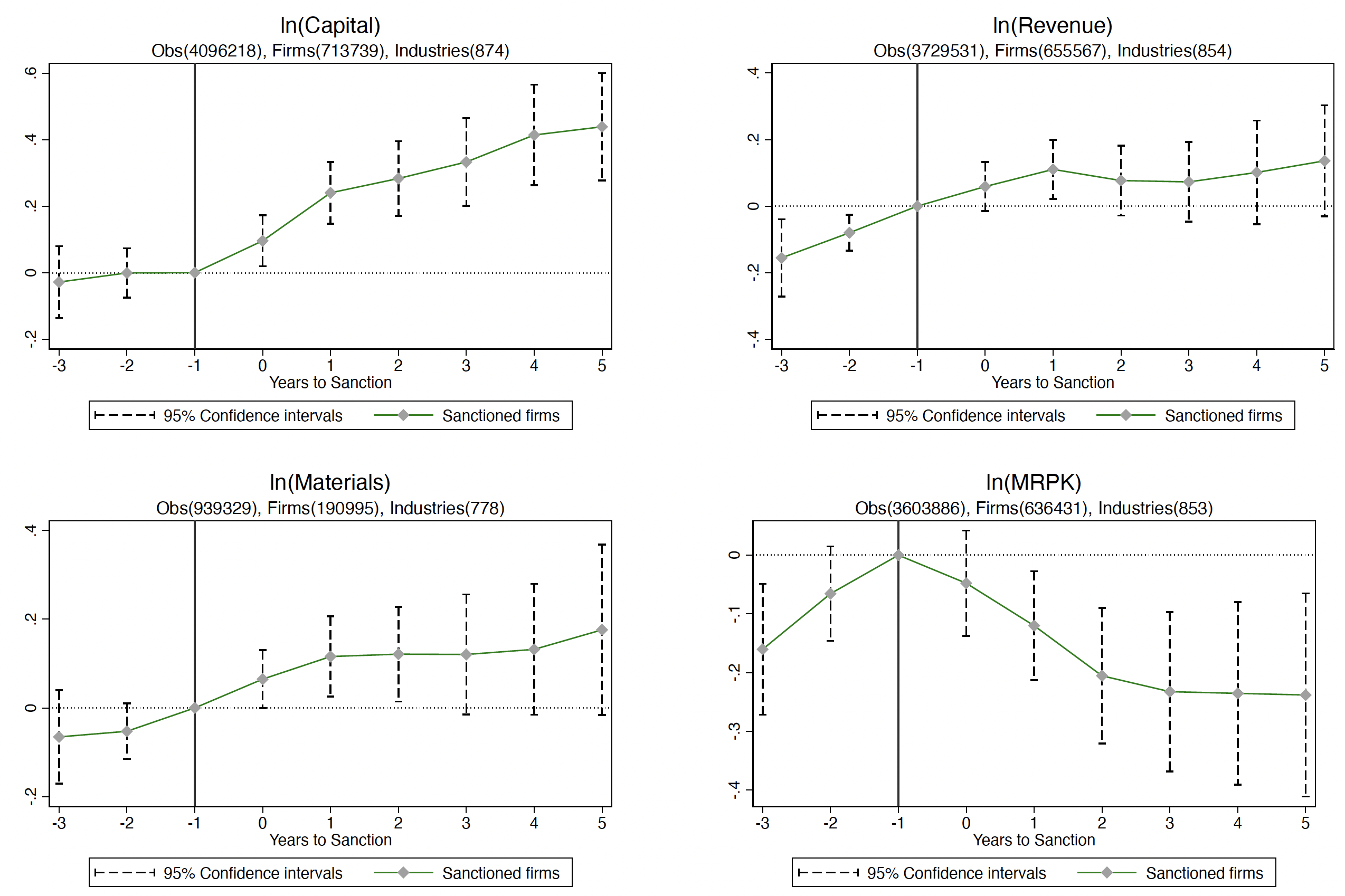

First, how did the firms react to being sanctioned relative to non-sanctioned firms and relative to not-yet-sanctioned firms? In my paper (Nigmatulina 2022), I use data on over 600,000 Russian firms across 2012-2020 and look at the effects on sanctioned firms’ inputs and outputs, relative to non-sanctioned firms. I find that capital and material inputs grew dramatically for the targeted firms after 2014 (Figure 1). When comparing firms that were sanctioned sooner to firms that are sanctioned later in Figure 2, I also find growth in inputs and outputs after being sanctioned (albeit with some anticipation effect for firms’ revenues).

Figure 2 Average effects of sanctions on sanctioned firms relative to not-yet-sanctioned firms, by year

Notes: Each dot is the coefficient on the indicator of being observed t years after the sanctions announcement. Outcome variables: natural logs of ‘Capital’, ‘Revenue’, ‘Materials’ and ‘Marginal Revenue Product of Capital’ (‘MRPK’). Controls for 4-digit industry-by-year fixed effects, firm size-by-year fixed effects (estimated using the full sample), firm fixed effects. Clustering is at the firm and industry-by-year level.

Explaining the positive overall effect of sanctions on sanctioned firms

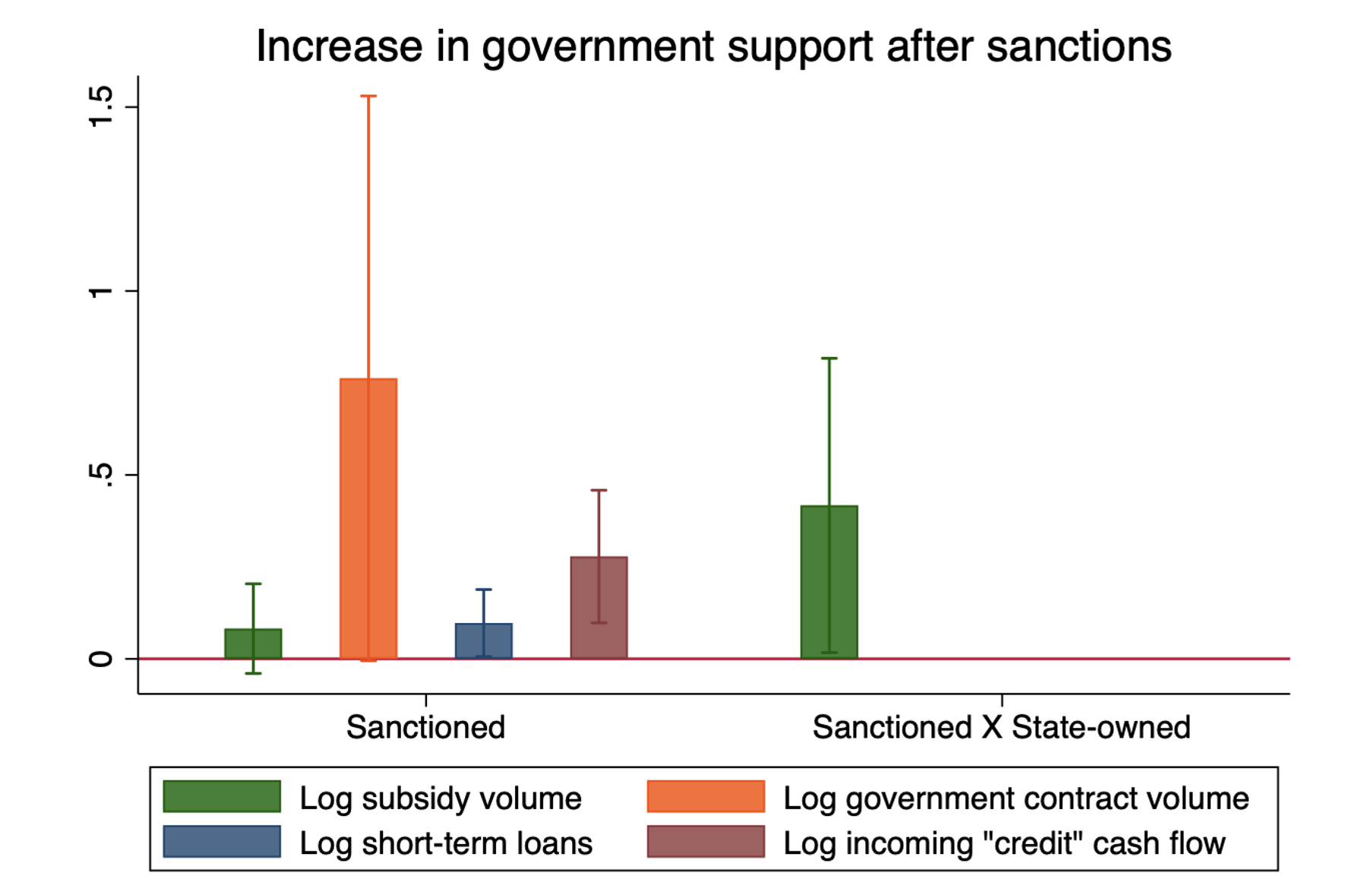

I collect and study additional outcome variables affecting inputs and revenues for the sanctioned firms: loans, subsidies, and government contracts. I find an increase in all three of these variables after treatment in Figure 3 and a differential further growth in subsidies for state-owned enterprises. This finding is consistent with the government compensating the targeted firms for the sanctions through several channels: inputs with subsidies and loans and outputs with contracts. This result, demonstrating the importance of the mitigation of the direct effect of sanctions, complements the work of Mamonov et al. (2022) who found that Russian banks have anticipated the gradually expanding sanctions, front-loading borrowing and withdrawing assets from abroad in advance of treatment.

Figure 3 Regression coefficients for outcome of sanctions on natural logs of subsidy volume, government contract volume, incoming credit-related cash flow, short-term loans

Note: Controls are: 4-digit industry-by-year fixed effects, firm size-by-year fixed effects (estimated using the full sample), firm fixed effects. Subsidy regression includes an interaction term for sanctioned X state-owned.

Aggregate real effects of sanctions

The aggregate effect of sanctions on the macroeconomy depends on whether the treated firms were over-resourced or under-resourced before sanctions. If these firms were over-resourced, and their resources further increased relative to other firms, the economy became less efficient in the aggregate.

I measure how much revenue is produced using the amount of capital and labour used – the marginal revenue product of capital (MRPK) – to measure the resources that the to-be-sanctioned firms had before 2014. I find that these targeted firms already had too much capital relative to the revenue they generated prior to sanctions. In the absence of government protection, the sanctions would have improved Russian economy-wide productivity by taking away resources from the firms that had too many. However, thanks to government protection, the sanctioned firms gained resources relative to all other firms, rather than lost them. The capital input increased more than the revenue, so MRPK for targeted firms declined. The efficiency gap between sanctioned and non-sanctioned firms has increased as a result.

I look sector by sector and find that in 45 out of 50 sectors total factor productivity declined. Using a model, I calculate the aggregate change from the whole economy and firms and find that the aggregate total factor productivity declined by at least 0.33%, reaching up to 3% declines in relevant sectors. If we assume that total capital resources in the economy also went down as a result of sanctions, Russian GDP shrinks by even more than 0.33%.

From these patterns, one can conclude that smart sanctions have not worked as intended. If their goal was to hurt the chosen targets and not the average citizen, they have failed. However, they have failed because the Russian government has stepped in and supported the targets. Because subsidies, government contracts, and loans have increased more for sanctioned firms, they have been shifted away from other firms and citizens. In other words, the government has saved the targets at the expense of everyone else.

The mechanics shown in this study are relevant for the most recent sanctions episode in 2022. Sanctions targeting strategic firms and sectors may not stop their expansion at the expense of others. For example, the budget for “national defence” this year is planned to exceed former projections by a third, or 1.2 trillion roubles (over 1% of Russian GDP) and is expected to grow even more next year (Forbes 2022). When evaluating the effectiveness of sanctions, and the choice of targets, one must take into consideration the endogenous response of the Russian government that will absorb the direct economic effect of sanctions.

References

The Swiss Confederation in cooperation with the United Nations Secretariat Thomas J. Watson Jr. Institute for International Studies (2001), Targeted Financial Sanctions. A Manual for Design and Implementation, Contributions from the Interlaken Process.

Felbermayr, G, A Kirilakha, C Syropoulos, E Yalcin and Y V Yotov (2020), “The Global Sanctions Data Base”, European Economic Review 129: 103561.

Mamonov, M, A Pestova, A and S Ongena (2021), “"Crime and Punishment?" How Russian banks anticipated and dealt with global financial sanctions”, VoxEU.org, 10 June.

Nigmatulina, D (2021), “Sanctions and Misallocation. How Sanctioned Firms Won and Russia Lost”.

Schachter, H (2022), “Расходы бюджета России по статье «национальная оборона» в 2022 году выросли на треть”, Forbes.

SECO – State Secretariat for Economic Affairs (2017), “Smart sanctions – targeted sanctions”.