The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) has recently warned that climate change could cause an increase in the frequency and intensity of natural disasters, even in the optimistic scenario of a temperature increase by 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels. This development will potentially have devastating effects on vulnerable communities which are unable to cope with the humanitarian and economic risks arising from floods, storms and other adverse events (IPCC 2018). Therefore, international humanitarian aid aiming to alleviate human suffering and economic losses is expected to increase in importance.

In order to facilitate rapid and efficient assistance that is independent of international and domestic politics, such aid is supposed to follow the principle of impartiality. The principle is firmly established in international law and dictates that humanitarian action should be implemented “solely on the basis of need, without discrimination on the grounds of other factors such as sex, ethnic affiliation, religion or political views” (Persson 2004). Whether humanitarian aid meets these standards is, however, questionable. A prominent example relates to cyclone Nargis in 2008. The natural disaster killed approximately 140,000 people and affected millions in Myanmar. While the need for international relief efforts was unquestionable, the government of Myanmar was accused of systematically blocking and delaying the entry of humanitarian aid for political reasons, as well as of preferentially channelling some of it to its own ethnic group (EAT and CPHHR 2008). More systematic evidence for political interference in humanitarian aid is also available. According to Drury et al. (2005), the decision to grant US humanitarian aid is highly political and strongly influenced by diplomatic alliances, regime types and US media coverage. Similarly, Eisensee and Strömberg (2007) demonstrate that natural disasters that receive larger coverage in US evening news have a higher probability to receive US assistance. They attribute this to the interests of the US government, either because citizens lobby for aid or because politicians aim to benefit from positive reporting about an issue that voters care about.

While these studies reveal important insights on how US politics affect the allocation of humanitarian assistance, in our own recent work, we focus on the role of political factors within recipient countries (Bommer et al. 2019). Anecdotal evidence from policy reports by the Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies (Klynman et al. 2007) and the International Dalit Solidarity Network (2013) suggest that power relations at the community level within recipient countries can distort the allocation of humanitarian aid. We broaden this perspective by focusing on national political leaders in disaster-affected countries. Specifically, we investigate whether natural disasters hitting the birth region of political leaders receive more humanitarian support from the United States.

Previous research suggests that birth regions of political leaders receive favourable treatment in a number of dimensions, as evidenced in economic activity as measured by nightlight intensity in more than 120 countries (Hodler and Raschky 2014), governmental resources in Norway (Fiva and Halse 2016) and Italy (Carozzi and Repetto 2016), infrastructure in Vietnam (Do et al. 2017) and Chinese aid in Africa (Dreher et al. 2019). Perhaps one of the most intriguing manifestations of this phenomenon occurred in Ivory Coast in 1983, when the Ivorian president decided to relocate the nation’s capital from heavily populated Abidjan to his birthplace Yamoussoukro, a village of 15,000 inhabitants at the time (Rice 2008). Such favourable treatment has been suggested to be the result of leaders preferring their hometowns for intrinsic reasons or of attempts to ensure electoral or political support from their stronghold.

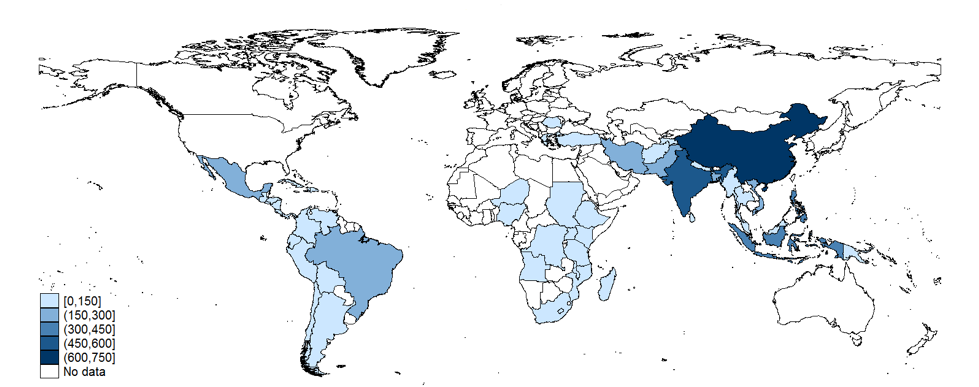

In Bommer et al. (2019), we examine the existence of a ‘home bias’ in the allocation of humanitarian aid from the US for 6,228 rapid-onset natural disasters, such as floods, storms and earthquakes, striking 50 countries over the 1964-2017 period (see Figure 1).

Figure 1 Number of natural disasters in our sample of the 50 aid-receiving countries most frequently affected by rapid-onset disasters over the 1964-2017 period

We take these data from the Office of US Foreign Disaster Assistance (OFDA), which responds to an average of 65 disasters in more than 50 countries per year (USAID 2018). The response usually follows a two-step procedure. It begins with a local US diplomat responding to an assistance request from the recipient country’s government, for which a limited amount of up to $50,000 is available. In a second step, the OFDA officials coordinate with the government of the affected countries to determine whether and how much additional aid the OFDA should give. Importantly, while the level of coordination can vary, the governments of the affected countries are typically involved in the needs assessments by the OFDA. These serve as a basis for determining additional aid amounts (OFDA 2010). Hence, political motives from both donors and recipients can find their way into the processes to make allocation decisions.

We test the existence of a home bias in the allocation of disaster aid by comparing aid that is allocated as a consequence of disasters hitting the birth region of political leaders with that of disasters hitting non-birth regions. In doing so, we face the problem that any difference in allocation could be a reflection of differences in need rather than home bias, for example because (birth) regions with political ties to the government are richer and better protected against the risks arising from natural disasters compared to other areas. To ease such concerns and establish a causal effect of leaders’ birth regions, we follow three strategies. First, we compare regions that are similar on a range of observable characteristics of the affected subnational area such as nightlight intensity, population density and ruggedness. Second, we only compare disasters that hit the same areas repeatedly, testing whether or not they receive more aid at times the current leader of the country was born there. In a third approach, we compare disasters hitting the birth region of the current leader with disasters affecting areas that are not birth regions at the time of the disaster, but during the previous or subsequent period. This allows us to exploit a discontinuity introduced by leader changes. As unobserved confounding variables are unlikely to exhibit discontinuities that are simultaneous to leader changes, this approach comes closest to measuring a causal effect.

Our findings suggest that favouritism towards the birth region exerts a strong and robust influence on the amount of humanitarian aid. Depending on the specification, the increase in funding when disasters hit a birth region is 45%-85%, on average, compared to when another region is hit. However, we do not find evidence for a systematic birth region effect on the probability of receiving US-provided disaster relief.

To shed light on these results, we investigate whether US political and economic interests facilitate the home bias. We find that neither geopolitical alignment nor commercial relations with the US influences its size. On the contrary, recipient-country characteristics in which leaders should find it easier to misappropriate funds – such as clientelism prevailing in public spending or low bureaucratic quality – explain a substantial share of it. The involvement of the government in damage assessments, as well as the difficulties in verifying information the government provides, seem to enable country leaders to favour their birth regions. Finally, providing a novel dataset on ethnic power relations, we show that the observed favouritism is not explained by the geographic overlap of birth regions with ethnic homelands of country leaders, but constitutes instead a self-sustained, independent dimension of favouritism.

Taking a unique perspective that puts the political power of the disaster-affected population at its centre, our study uncovers an alarming distortion to the impartiality principle for US humanitarian aid.1 Our results indicate that the US did not prevent the recipients of its humanitarian aid from allocating it towards their leaders’ birth regions. Politically marginalised groups might suffer as a consequence. In order to address this violation of the impartiality principle, the US government – as well as other aid donors with similar bureaucratic structures – should acknowledge the importance of internal political dynamics and revise its processes for disaster damage assessment and aid allocation accordingly.

References

Bommer, C, A Dreher and M Perez-Alvarez (2019), "Home bias in humanitarian aid", CEPR Discussion Paper DP13957.

Carozzi, F and L Repetto (2016), "Sending the pork home: Birth town bias in transfers to Italian municipalities", Journal of Public Economics 134: 42–52.

Dreher, A, A Fuchs, R Hodler, B Parks, P Raschky, and M Tierney (2019), "African leaders and the geography of China’s foreign assistance", Journal of Development Economics 140: 44–71. See also on VoxDev.

Drury, A C, R S Olson, and D A Van Belle (2005), "The politics of humanitarian aid: US foreign disaster assistance, 1964-1995", Journal of Politics 67(2): 454–473.

Do, Q-A, K-T Nguyen, and A N Tran (2017), "One mandarin benefits the whole clan: Hometown favoritism in an authoritarian regime". American Economic Journal: Applied Economics 9(4): 1–29.

EAT and CPHHR (2008), After the storm: Voices from the delta, 2nd edition.

Eisensee, T and D Strömberg (2007), "News droughts, news floods, and US disaster relief", Quarterly Journal of Economics 122(2): 693–728.

Fiva, J H and A H Halse (2016), "Local favoritism in at-large proportional representation systems", Journal of Public Economics 143: 15–26.

Hodler, R and P A Raschky (2014), "Regional favoritism", Quarterly Journal of Economics 129(2): 995–1033.

International Dalit Solidarity Network (2013), Equality in aid: Addressing caste discrimination in humanitarian response, Copenhagen, Denmark.

IPCC (2018), Global Warming of 1.5°C. An IPCC Special Report on the impacts of global warming of 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels and related global greenhouse gas emission pathways, in the context of strengthening the global response to the threat of climate change, sustainable development, and efforts to eradicate poverty. [Masson-Delmotte, V., P. Zhai, H.-O. Pörtner, D. Roberts, J. Skea, P.R. Shukla, A. Pirani, W. Moufouma-Okia, C. Péan, R. Pidcock, S. Connors, J.B.R. Matthews, Y. Chen, X. Zhou, M.I. Gomis, E. Lonnoy, T. Maycock, M. Tignor, and T. Waterfield (eds.)].

Klynman, Y, N Kouppari and M Mukhier (2007), World disasters report: Focus on discrimination. Geneve, Switzerland: International Federation of Red Cross & Red Crescent Societies.

Konyndyk, J and R Worden (2019), "People-driven response: Power and participation in humanitarian action", CGD Policy Paper 155.

OFDA (2010), Annual Reports.

Persson, G (2004), "The government’s humanitarian aid policy", Government Communication 2004/05: 52

Rice, X (2008), "The president, his church and the crocodiles", New Statesman, 23 October.

USAID (2018), "Office of U.S. disaster foreign disaster assistance".

Endnotes

[1] Interestingly, our novel focus on the disaster-affected population has recently been matched in the policy arena by former USAID Director Jeremy Konyndyk and Rose Worden (2019), who suggest involving currently peripheral voices of directly affected populations in decision-making processes.