Research on racial economic disparities in the US has documented that they are large and persistent and that they interact with monetary policy (Bartscher et al. 2020, Margo 2016, Derenoncourt et al. 2022). Studies of European countries have extensively analysed various dimensions of inequality and household heterogeneity, including issues related to age, education (skills), and gender. In our recent paper (Dossche et al. 2022), we provide comprehensive evidence on the existing economic differences between households born in their current country of residence (‘non-immigrants’) versus elsewhere (‘immigrants’), representative for the euro area. This aspect of heterogeneity is important because migrant gaps are significant, even exceeding gender gaps. Furthermore, differences between immigrants and non-immigrants matter for monetary transmission because immigrants are more sensitive to aggregate economic shocks and monetary policy.

First-generation immigrants make up about 15% of the euro area population, and migration into the euro area has increased significantly over the past 15 years. To distinguish between the countries of origin, we focus on economic differences between non-immigrants (households born in their current country of residence), EU-born immigrants (households whose head was born in an EU country different from their country of residence), and non-EU-born immigrants (households whose head was born outside the EU). We report two sets of results: structural, which reflect differences that persist over many years, and cyclical, which are differences that may affect the response of households to shocks and policies over the business cycle.

Structural evidence

Using data from two surveys representative of the euro area – the Household Finance and Consumption Survey and the EU Statistics on Income and Living Conditions – we first document unconditional differences in hourly wages and net wealth. These variables are key determinants of households’ consumption and welfare.

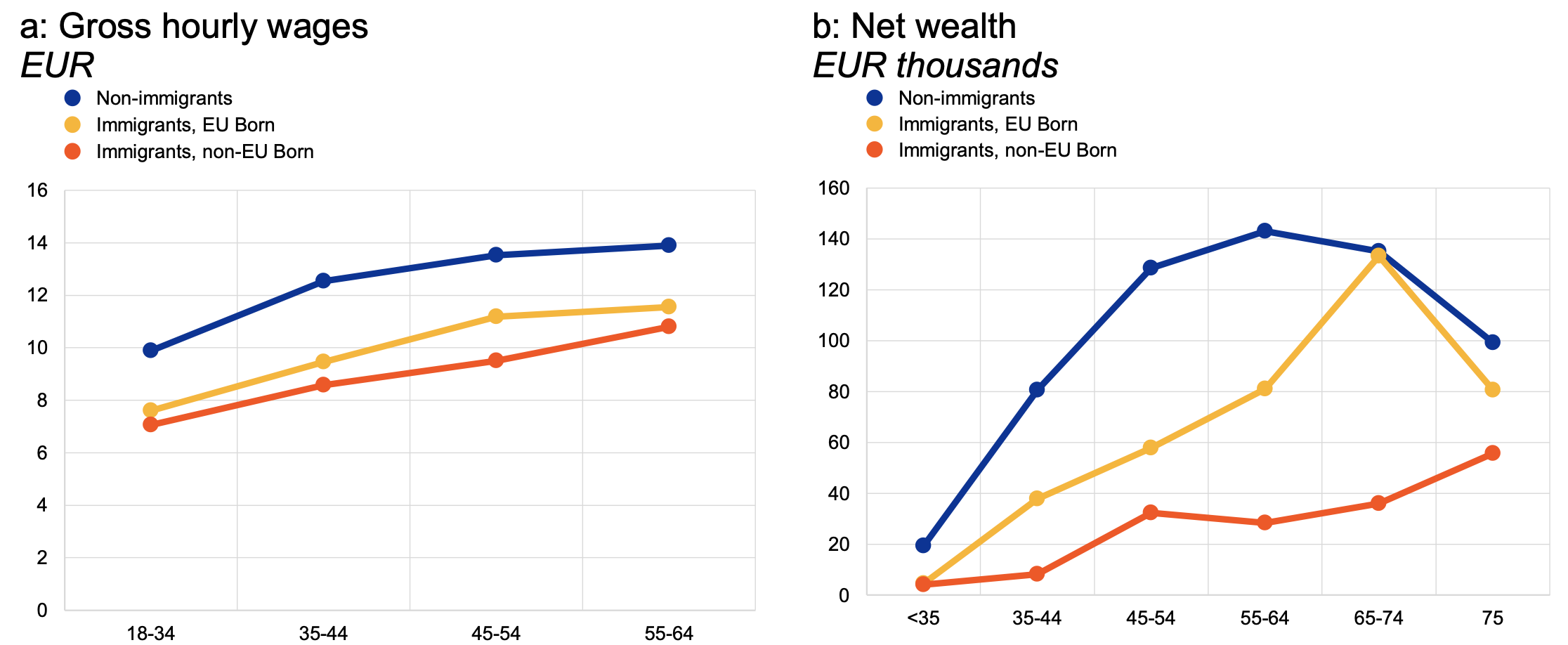

Figure 1 Median hourly wages and net wealth by age and country of birth

Sources: Household Finance and Consumption Survey 2010, 2014, 2017; EU Statistics on Income and Living Conditions 2009–2018, Italy: 2009–2017.

Notes: Hourly wages are calculated for employed individuals aged 18–64. Due to data limitations, the chart on hourly wages shows data for France, Italy, and Spain; the chart on net wealth shows data for Germany, France, and Italy.

We find that non-immigrants earn substantially higher wages than immigrants across all age groups (Figure 1a). Workers born in another EU country earn by about 20% less than non-immigrants, and those born outside the EU by about 25% less. The gap persists over the life cycle.

The differences in net wealth are substantially larger than for wages (Figure 1b). The gap is particularly wide for households born outside the EU, who at the age of 55 own a median net wealth of roughly €40,000 compared to €180,000 for non-immigrants. Similar to wages, the differences persist over the life cycle, with little convergence before retirement.

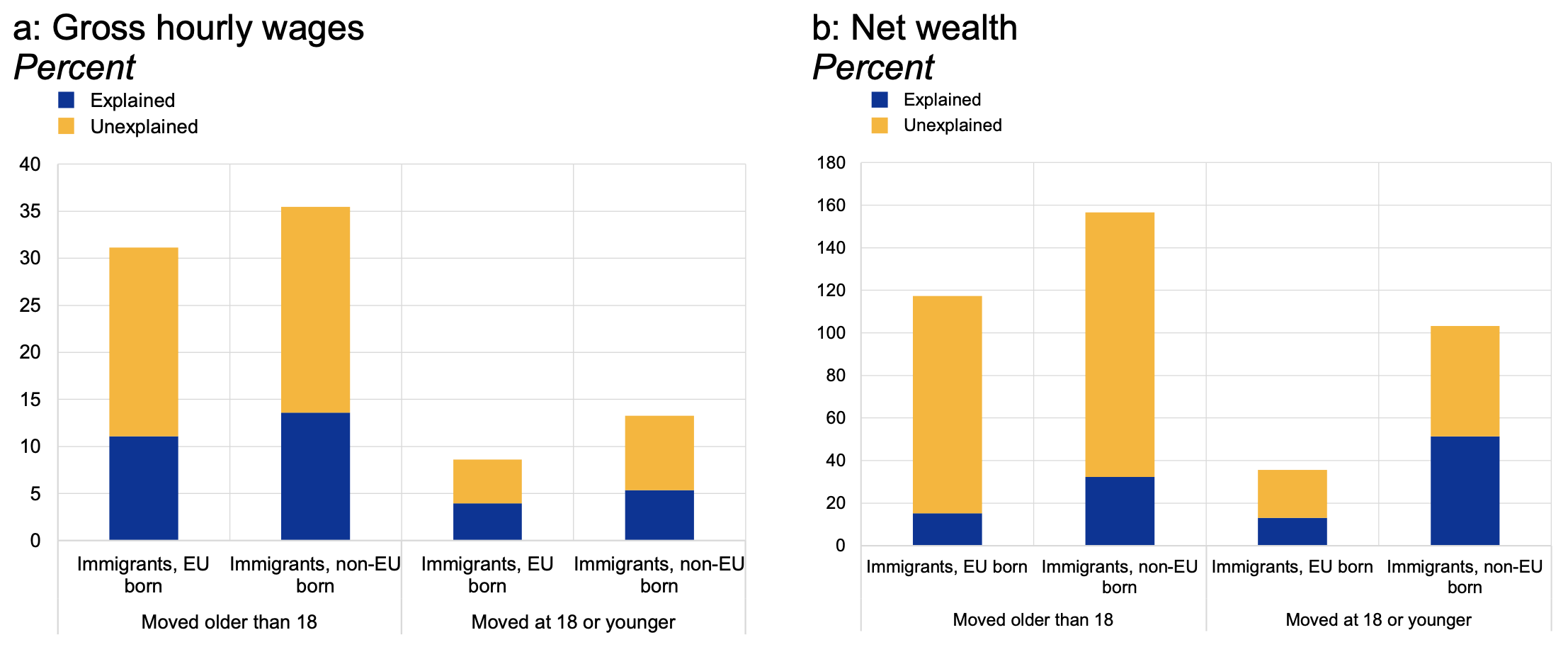

We investigate to what extent these gaps can be explained by differences in demographics. We estimate the Oaxaca–Blinder decomposition, a standard tool used to separate the role of observable differences (due to demographics) from the remaining differences, which can be attributed to unobservable characteristics such as preferences, culture, discrimination, and omitted variables not included in the regressors. Our demographics include marital status, gender, presence of children in the household, education, age, occupation, and the sector of employment. We find that only a small fraction of the gaps – around 30% – can be explained by these variables.

The gaps are substantially smaller for people who immigrated at a young age and who spent a longer time in the current country of residence (Figures 2a and 2b). However, the gaps do not close completely: they are by roughly 60% lower for people who moved into the country before the age of 18, both for EU and non-EU immigrants. This finding suggests that the length of time spent in the current country of residence gradually reduces the gaps. In addition, the share of the explained part on the total gaps is higher for younger immigrants.

Figure 2 Oaxaca–Blinder decompositions depending on the age of arrival in the country

Sources: Household Finance and Consumption Survey 2010, 2014, 2017; EU Statistics on Income and Living Conditions 2009–2018, Italy: 2009–2017.

Note: The charts compare estimates for people who moved to the country of residence before the age of 18 and after. The charts decompose the average gaps between non-immigrant and immigrant households into a part explained by observable variables and an unobserved part. The observable variables are: age, gender, marital status, education, presence of a child in the household, occupation, the sector of employment, employment dummy, self-employment dummy, and time fixed effects. Net wealth was transformed using the inverse hyperbolic transformation (to account for the presence of zero and negative values). The top and bottom 5% of values were winsorised.

Cyclical evidence

Differences between immigrants and non-immigrants also matter for the response of the macroeconomy to shocks at the business cycle frequency. The literature on Heterogeneous Agent New Keynesian models (starting with Kaplan et al. 2018) has identified two important objects: the share of constrained households and the sensitivity of incomes of individual households to changes in aggregate employment, i.e. ‘worker betas’.

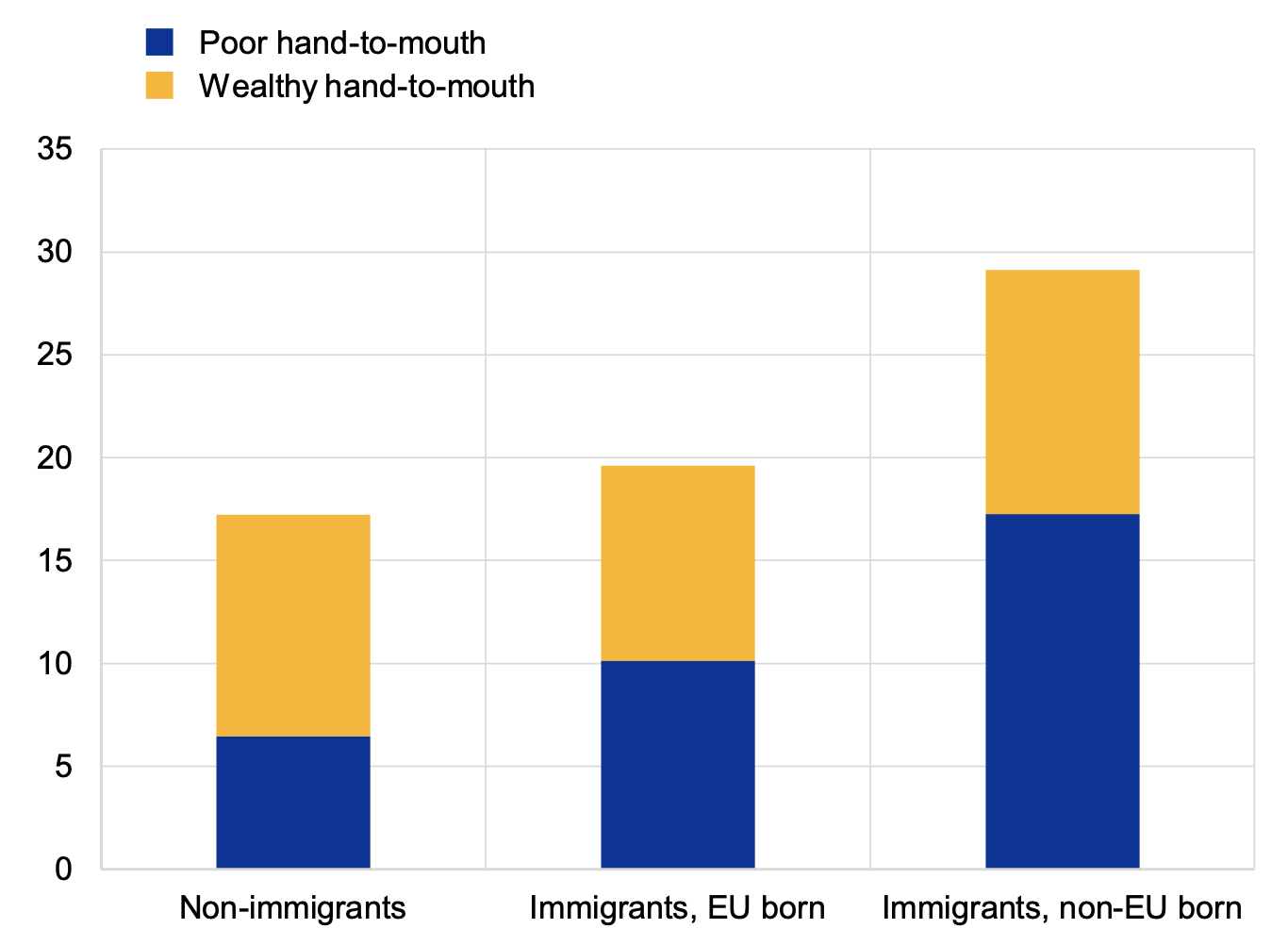

The share of constrained households (households with low holdings of liquid assets) affects monetary transmission: because their spending is more sensitive to income and wealth shocks, they have higher marginal propensities to consume than households who hold adequate liquid assets. We define constrained households, following Kaplan et al. (2014), roughly as those with liquid assets that do not exceed two weeks’ worth of monthly disposable income. Among non-immigrants, 15% of households are constrained; for immigrants, the share of constrained households is 18% and 29% for EU born and non-EU born, respectively (Figure 3). EU-born and in particular non-EU-born immigrants thus tend to hold substantially lower amounts of liquid assets. At the age of 55, median liquid assets of non-EU-born immigrants are around €1,500, whereas median liquid assets of EU-born immigrants are around €8,000 and of non-immigrants around €11,000. Hence, immigrants and particularly non-EU immigrants are likely to reduce their spending more severely in response to negative income and wealth shocks.

Figure 3 Share of constrained (hand-to-mouth) households by country of birth (percent)

Sources: Household Finance and Consumption Survey 2017.

Notes: The chart shows the share of the two types of hand-to-mouth households for non-immigrant households, households born in another EU country, and those born in a country outside the EU. Poor hand-to-mouth households do not own illiquid assets (most importantly housing); wealthy hand-to-mouth do. The estimates are based on an aggregate of France, Germany, Italy, and Spain. Sources: Labour Force Survey 2005-2019, quarterly data.

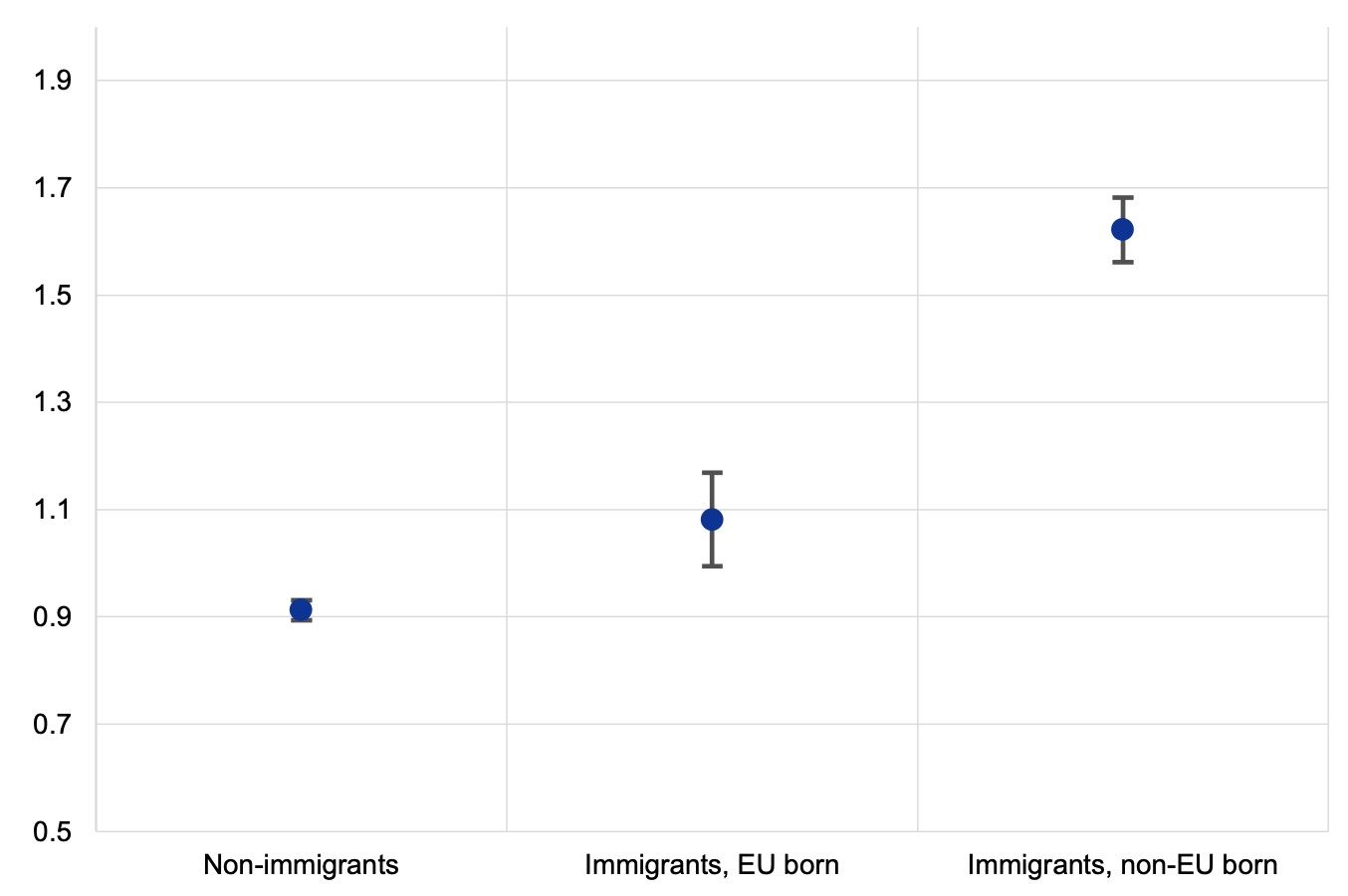

Figure 4 Sensitivity of individual employment to aggregate employment by country of birth (percent)

Notes: The chart shows the sensitivity of individual employment to aggregate employment for non-immigrant households, households born in another EU country, and those born in a country outside the EU. The estimates average to one and are based on an aggregate of France, Germany, Italy, and Spain. The lines indicate the 95% confidence interval.

The sensitivity of employment of individual immigrant households to changes in aggregate employment also significantly exceeds the sensitivity for non-immigrants (Figure 4). A sensitivity higher than one indicates that employment of that group of households reacts particularly strongly to aggregate shocks. While the sensitivity among immigrants amounts to 1.15 and 1.65 for EU-born and non-EU-born respectively, it is only 0.9 for non-immigrants. Immigrants are thus also particularly sensitive to the business cycle: they disproportionately lose during recessions when aggregate employment is lower, and strongly benefit from recoveries.

Summing up

We document substantial differences in income and wealth between non-immigrants and immigrants in the euro area. Only a small share of these differences can be explained by differences in demographics, while the majority is due to unobservable factors. We show that people born abroad are much more likely to be constrained (i.e. accumulate much lower amounts of liquid assets) and that their employment is particularly sensitive to the business cycle. These facts suggest that consumption among immigrants is likely to be more volatile.

Our findings are relevant both for researchers and policy makers. From a modelling perspective, our estimates can be used to calibrate and test models with household heterogeneity, including heterogeneous agent New Keynesian (HANK) models. Additional modelling analysis of this aspect of household heterogeneity would be useful as it would allow us to investigate how various policies affect the welfare of non-immigrant and immigrant households and how such heterogeneity affects aggregate dynamics. In addition, our results are informative for policy makers, who need to keep in mind distributional effects of alternative policies on various groups of households and implications of their actions for inequality.

While our analysis documents substantial socioeconomic differences between non-immigrants and immigrants, better data are needed to uncover the underlying drivers and are key to assessing the role of structural policies for reducing disparities between non-immigrants and immigrants.

Authors’ note: The views expressed in the column are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the European Central Bank and the Eurosystem.

References

Bartscher, A, M Kuhn, M Schularick and P Wachtel (2021), “Monetary policy and racial inequality”, VoxEU.org, 10 February.

Derenoncourt, E, C H Kim, M Kuhn and M Schularick (2022), “Wealth of two nations: The US racial wealth gap, 1860–2020”, VoxEU.org, 4 July.

Dossche, M, A Kolndrekaj, M Propst, J Ramos Perez and J Slacalek (2022), “Immigrants and the distribution of income and wealth in the euro area: first facts and implications for monetary policy”, working paper 2719, European Central Bank.

Kaplan, G, B Moll and G L Violante (2018), “Monetary policy according to HANK”, American Economic Review 108(3): 697–743.

Kaplan, G, G L Violante and J Weidner (2014), “The wealthy hand-to-mouth", Brookings Papers on Economic Activity 45(1): 77–153.

Margo, R (2016), “The persistence of racial inequality in the US”, VoxEU.org, 8 June.