The vast majority of the content made available on the web is financed through ad revenue. So a threat to advertising revenue stands as a threat to the continued production and availability of content to web users. The past few years have seen the appearance of a new technology – ad-blocking extensions to web browsers that allow users to obtain information on the web without seeing the ads embedded in web sites and therefore without providing the websites’ owners with revenue. Theoretical analyses of ad blocking predict potentially damaging impacts (Anderson and Gans 2011).

Since the widespread diffusion of ad blockers in 2012, the share of web users employing them has reached somewhere between 10% and 25% according to various sources.1 The widespread use of ad blockers raises the possibility of the disruption of content creation on the web. This is the question we explore in a recent working paper (Shiller et al. 2017).

We seek to determine whether ad blocking is undermining incentives for content creation. The mechanism we have in mind is that ad blocking deprives sites of revenue. In response, the sites invest less in content, and the degraded content attracts fewer site visitors. Exploring this mechanism empirically is challenging because we cannot observe sites’ advertising revenue.

What we can do, however, is observe both measures of site traffic as well as site-specific measures of the share of users arriving with ad blockers engaged, from PageFair (one of the study’s authors is an employee of PageFair). In particular, we observe Alexa traffic ranks for approximately 2,500 sites from 2013-2016, as well as the share of each site’s users blocking ads (mostly during 2015). Because ad blocking was negligible prior to 2013, we treat the level of ad blocking we observe as the change in ad blocking.

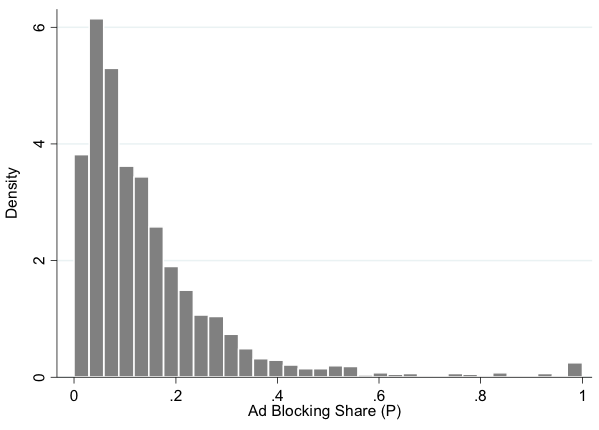

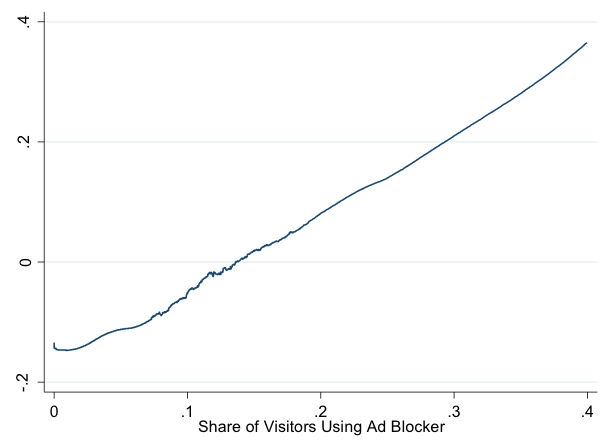

This allows us to ask how changes in traffic vary between sites experiencing smaller or larger increases in ad blocking over the period 2013-2016. In order to identify an impact of a growth in ad blocking on traffic, we require cross-site variation in ad blocking - and the extent of ad blocking varies substantially across the websites in our sample. The median share is 10.1%, and the interquartile range runs from 5.2% to 18.4%, as Figure 1 shows. We find that websites experiencing a greater share of visitors blocking ads also experience worsening traffic ranks relative to less affected websites, indicating that affected sites become relatively less appealing to potential visitors. More specifically, we find each additional percentage point increase in ad blocking rates corresponds to a 0.6% worsening in traffic rank (see Figure 2). Based on estimates of the cross-sectional rank-traffic relationship for selected sites, we can estimate that a 1 percentage point increase in ad blocking reduces a site’s traffic by 0.67%.

Figure 1 Distribution of ad blocking visitor share across sample websites

Figure 2 Eventual ad block share and site rank change, 2013-2016

The effects of ad blocking on site revenue are compounded by that fact that ad blocking both reduces overall traffic and denies sites revenue from visitors using ad blockers. If 10% of a site’s users block ads (and if ad revenue is proportional to paid traffic), then we would expect a mechanical 10% reduction in revenue. But over the long term, as site investment and quality declines, our results also imply a 6.7% reduction in overall traffic. Hence the long-run revenue effect of having 10% of a site’s visitors blocking ads exceeds the direct 10%; rather, it is 16%.2

We find that sites with higher ad blocking experience greater declines in their traffic, so we need to be on guard to the possibility that some external factor is both reducing the sites’ appeal and driving their users to engage ad blockers. The distinction between the long- and short-run effects of ad blockers provides some corroborating evidence.

In the short run – before sites have a chance to change their investment – ad blocking should just increase traffic. Sites haven’t had a chance, or the need, to adjust their quality, so users employing ad blockers can access the same quality content without the nuisance of ads. Users of ad blockers, some of whom had been unwilling to visit the sites without an ad blocker, would now find the site more attractive and might now visit. In the short run, we would therefore expect sites with a greater share of potential users employing ad blockers to experience increased traffic. In the longer run, by contrast, sites deprived of revenue would decrease their investment along the lines outlined above. While we find a worsening in traffic for sites with more ad blocking users over the three-year period, we find no such worsening during 2013. Rather, sites with higher shares of eventual ad blocking users experience increases in traffic during 2013, a pattern that reverses in the longer-run period of 2013-2016. This provides some assurance that the site degradation that we document is caused by ad blocking.

The content-threatening problems created by ad blocking have a number of possible remedies. Sites can move from ad support to paywalls, although this transition has been difficult for all but the most popular information sources (Chiou and Tucker 2013). Sites can also prevent users with ad blockers engaged from visiting their sites. This strategy is challenging for sites to undertake unilaterally when other sites offer similar content, and losing any visitors – including those who block ads – lowers a site’s visibility and search engine rank. While they oppose ad blockers, advertisers themselves recognise that excesses in web advertising – long load times, privacy-invading cookies, and even malware – have driven users to protect themselves with ad blockers. Advertising associations are now exploring advertising best practices in order not to sour users on all advertising.3 Finally, regulators might consider whether coordination among sites in preventing access by users with ad blockers engaged necessarily runs afoul of antitrust rules.

References

Anderson, S P and J S Gans (2011), "Platform Siphoning: Ad-Avoidance and Media Content." American Economic Journal: Microeconomics, 3(4): 1-34.

Chiou, L and C Tucker (2013), "Paywalls and the demand for news." Information Economics and Policy, 25(2), 61-69.

Shiller, B, J Waldfogel and J Ryan (2017), “Will Ad Blocking Break the Internet?”, NBER Working Paper No. 23058.

Endnotes

[1] See https://pagefair.com/blog/2015/ad-blocking-report/ and https://www.wsj.com/articles/ad-blockers-are-employed-by-10-of-u-s-desktop-users-comscore-finds-1459501262 .

[2] Note that 1- (1-0.10)(1-0.10(0.67))=0.16.

[3] https://www.iab.com/insights/ad-blocking-blocks-ads-win-back/