The impacts of the global financial crisis on poverty and income distribution in developing countries have proved difficult to track because real-time data are typically not available. Measuring these impacts is important not only for designing policy responses to the current shock, but also to mitigate the impact of future economic shocks.

To bridge the knowledge gap, we use a “microsimulation” approach that superimposes macroeconomic projections on behavioural models built on pre-crisis household data. Our model is based on those developed by Bourguignon et al. (2008) and Ferreira et al. (2008), but simplified by linking the simulations to macroeconomic projections (instead of a general equilibrium model) to extrapolate future household level impacts for a specific country. Macroeconomic shocks are transmitted to households through changes in employment, earnings and non-labour income (including remittances), and comparisons are made between scenarios with and without crisis for the same year, or between pre-crisis and post-crisis years. Below we summarise our results for Bangladesh, Mexico, and the Philippines (for more detailed results see Habib et al. 2010a and 2010b). In the context of the financial crisis, similar approaches have been employed for select OECD countriesbut not in a systematic manner for developing countries to the best of our knowledge[1].

Impact on overall poverty and inequality

Increase in the level and depth of poverty as a result of the crisis is predicted for all three countries, with the extent of increase largely depending on the size of the macroeconomic shock. These results are consistent with Chen and Ravallion 2009 estimates of the crisis impact on global poverty.

In Bangladesh and the Philippines, where the crisis has led to a slowdown but not a reversal in GDP growth, poverty is expected to decline at a slower pace due to the crisis. In 2010, the poverty rate is expected to be higher by 1.2 and 1.5 percentage points than what it would have been without the crisis in Bangladesh and the Philippines respectively, which translates to approximately 1.4 and 2 million additional poor. In Mexico, GDP actually contracted by nearly 7% in 2009 and is expected to grow by just 3% in 2010. As a result, poverty rate is projected to rise by nearly 4 percentage points between 2008 and 2010. The crisis has no significant impact on the aggregate inequality index in all three countries, which is not surprising, given that a number of studies on past macroeconomic shocks have found similar results (see Aaberge et al. 2000 and Baldacci and Inchauste 2002).

The aggregate index, however, masks important changes in the underlying income distribution, some of which are summarised below.

Impact of the crisis on income distribution: Who is affected and how

In all three countries, the impacts are relatively large in the middle part of the income distribution – consistent with earlier studies that suggest economic crises can have disproportionate impact on this group[2]. Between 15 and 20% of households in the fourth to seventh decile of the income distribution in Mexico and the Philippines, and 10% of this group in Bangladesh, suffer income losses that push them to a lower income decile[3]. In Mexico, where the crisis has been more severe, significant impacts are also likely for the bottom of the distribution. The poorest 20% of Mexican households suffer an average per capita income loss of about 8%, compared with 5% for the entire population – even after existing safety net transfers that benefit many of the extreme poor are taken into account.

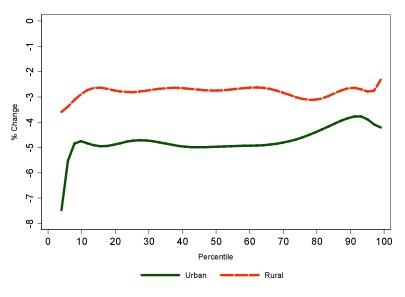

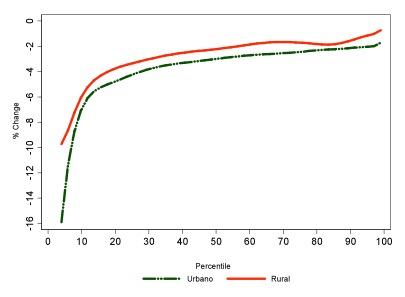

Impact on the middle of the distribution can be attributed to significant shocks to employment and labour earning in the manufacturing sector, which employ a large number of workers from middle-income households. Urban households suffer more losses, on average, than do rural households because the manufacturing sector is typically concentrated in urban areas. Urban-rural gap is the widest in the Philippines – a 6% decline in the per capita income of urban households is twice that of rural households.

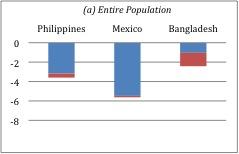

Beyond these common patterns, there is much variation in how impacts are distributed within countries because of differences in how the macroeconomic impacts are transmitted to households. Approximately 90% of the average loss in household income in Mexico and the Philippines are attributable to a fall in labour income, compared with 50% in Bangladesh where losses in remittances are equally important (see Figure 1a). Losses in remittances tend to be more concentrated among better-off households withinurban and rural areas than losses in labour income, mainly because the pre-crisis distribution of remittances was already skewed toward richer households.

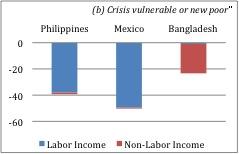

Figure 1. Changes in household incomes between no-crisis and with-crisis scenarios, 2010

Source: Authors’ calculations. Note: For Mexico, the change is from pre-crisis to post-crisis (2008 to 2010). Households projected either to fall into or to remain in poverty (rather than exit from it) as a consequence of the crisis.

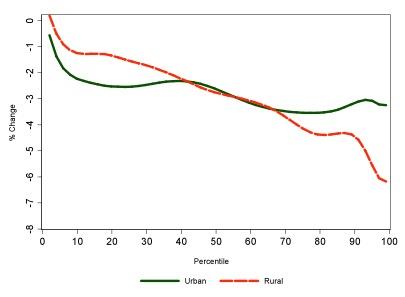

The combination of these factors generates distributional patterns that are different across urban and rural areas in different countries. The Philippines is characterised by a high level of urbanisation and a concentration of manufacturing and service sectors in urban areas, along with a relatively limited role of remittances. These translate into much larger income losses for urban areas compared with rural areas, but somewhat equitable distribution of losses within each area (Figure 2). In contrast, Bangladesh and Mexico are likely to see significant distributional changes within urban and rural areas. In Bangladesh, relatively better-off households in urban and rural areas alike suffer the greatest losses, mainly because of lower remittances due to the crisis. In Mexico, the losses are highest among the poor because of a substantial projected fall in labour income.

Figure 2. Growth incidence curves: Percent change in per capita income/consumption between no-crisis and with-crisis scenarios

a. Bangladesh

b. The Philippines

c. Mexico

Source: Authors’ calculations. Note: For Mexico, the change is from pre-crisis to post-crisis (2008 to 2010); for the other countries, the change is from no-crisis to with-crisis scenarios for the same year (2010).

The “crisis vulnerable”: a new challenge

The “crisis-vulnerable” are households that are predicted to be poor as a result of the crisis, but would not have been poor otherwise. The characteristics of these households are quite different from the chronically poor as well as the general population. On average, they appear to be more skilled and urban than the chronically poor, but less so than the general population. They also are more likely to be economically active than the chronically poor, indicating that the crisis would have significantly increased the number of “working poor.” Crisis vulnerable households suffer much larger income losses (25% - 50%) than the average household (3% - 5%) – mainly due to loss in labour income in Mexico and the Philippines and loss in remittances in Bangladesh (Figure 1b).

Relevance for policy

The results have a number of potential uses for policy design and monitoring.

- First, they help identify possible “leading indicators” that can be monitored rapidly to gauge the likely welfare impacts of a crisis, in the absence of real-time information on household welfare. Manufacturing employment, wages, remittance flows, and food prices emerge as potential candidates for monitoring in all three countries, with the relative importance of each indicator varying by country.

- Second, identifying households likely to suffer the most losses can inform the design of policy responses. For example, the difference in characteristics between the “crisis vulnerable” and the chronically poor suggests that expanding existing safety-net programs, targeted towards the chronically poor, to mitigate the losses of the crisis-affected may not be effective or practical. Instead, interventions that protect vulnerable households against risk may be required.

- The results have political economy implications as well. The substantial losses suffered by the urban middle-income and poor households, for example, are important because of the influence these groups can have on public perceptions and the government’s decision-making process.

Caveats

A number of caveats apply to these findings. An important caveat is one that applies to most microsimulations based on past data – the behavioural models underlying the simulations reflect the preexisting structure of labour markets and earnings and do not allow these to change over time. Also, since the three countries analysed here may not be representative of the developing world, caution is warranted in generalising these results to other countries or regions. In particular, the model may not be suitable to capture impacts for countries heavily dependent on commodity exports (for example, some African countries) or those where wealth shocks play a large part (for example, some countries in Eastern Europe)[4].

Editors’ Note: An earlier version of this note was published in the Economic Premise Series produced by the Poverty Reduction and Economic Management (PREM) Network Vice-Presidency of the World Bank. All authors work in the Poverty Reduction and Equity Group (PREM) at the World Bank.

References

Aaberge, Rolf, Anders Björklund, Markus Jäntti, Peder J Pedersen, Nina Smith, and Tom Wennemo (2000), “Unemployment Shocks and Income Distribution: How did the Nordic Countries Fare During their Crises?”, Scandinavian Journal of Economics, 102(1):77-99.

Ajwad, Mohamed Ishan, F Haimovich and M Azam (2009). The Employment and Welfare Impacts of the Financial Crisis in Latvia. Unpublished manuscript. Europe and Central Asia Human Development Group, World Bank, Washington, DC.

Baldacci, Emanuele, Luiz de Mello, and Gabriela Inchauste (2002), “Financial Crises, Poverty, and Income Distribution”, Working Paper 02/4, International Monetary Fund, Washington, DC.

Bourguignon, Francois, Maurizio Bussolo, and Luiz Pereira da Silva (2008), “Introduction: Evaluating the Impact of Macroeconomic Policies on Poverty and Income Distribution”, In Francois Bourguignon, Maurizio Bussolo, and Luiz Pereira da Silva (eds.), The Impact of Macroeconomic Policies on Poverty and Income Distribution, 1–23. Washington DC: World Bank.

Chen, Shaohua, and Martin Ravallion (2009), “The Impact of the Global Financial Crisis on the World’s Poorest”, World Bank Development Research Group.

Ferreira, Francisco H G, Phillippe G Leite, Luiz A Pereira da Silva, and Paulo Picchetti (2008), “Can the Distributional Impacts of Macroeconomic Shocks Be Predicted? A Comparison on Top-Down Macro-Micro Models with Historical Data for Brazil.” In Francois Bourguignon, Maurizio Bussolo, and Luiz Pereira da Silva (eds.), The Impact of Macroeconomic Policies on Poverty and Income Distribution, 119–75. Washington DC: World Bank

Habib, Bilal, Ambar Narayan, Sergio Olivieri, and Carolina Sanchez-Paramo (2010a), “Assessing ex ante the Poverty and Distributional Impact of the Global Crisis in a Developing Country: A Micro-Simulation Approach with Application to Bangladesh”, Policy Research Working Paper 5238, World Bank, Washington, DC.

Habib, Bilal, Ambar Narayan, Sergio Olivieri, and Carolina Sanchez-Paramo (2010b), “Assessing ex ante the Poverty and Distributional Impact of the Global Crisis in the Philippines: A Micro-Simulation Approach”, Unpublished manuscript. Poverty Reduction and Equity Group, World Bank, Washington, DC.

Ravallion, Martin (2009), “The Developing World’s Bulging (But Vulnerable) Middle Class”, Policy Research Working Paper 4816, World Bank, Washington, DC.

Zacharias, Ajit, Thomas Masterson, and Kijong Kim (2009), “Distributional Impact of the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act: A Microsimulation Approach”, Working Papers Series, Levy Economics Institute, Anandale-on-Hudson, New York.

[1] For the US, Zacharias et al. (2009) uses microsimulations to analyse the impact of the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act on employment, earnings and inequality.

[2] Ravallion (2009) argues that middle-income groups in developing countries are more exposed to crisis shocks than the rest of the population. Friedman and Levinsohn (2002) find that Indonesian households in the middle of the distribution were most adversely impacted by the 1997 crisis, mainly due to the impact on the urban poor.

[3] Each decile is equivalent to 10% of the country’s population, when households are ranked in terms of per capita income or consumption, with the 1st and 10th deciles being the poorest and richest groups, respectively.

[4] However, we find that some of the results from recent simulations and preliminary analysis of post-crisis household data from Eastern European countries are in line with the ones presented here (see Ajwad 2009).