There are two primary benefits, in trade terms, to membership of the EU. First, there are no tariffs or customs duties between member states. Second, there are efforts to minimise ‘non-tariff barriers’ (NTBs). In particular, there are EU-wide agreements on product standards and rules of origin. This means that firms who import goods from outside of the customs union can then trade those goods across borders within the union without being subject to additional checks. Upon leaving the EU, the UK will no longer be party to these agreements and as such, there is likely to be a significant increase in NTBs.

The impact of Brexit on the UK economy has been explored in previous work (Dhingra and Sampson 2016, among others), as has the effect on other EU member states (Aichele and Felbermayr 2015). Lawless and Morgenroth (2016) study the effect of Brexit on the Irish economy. However, the specific effect of the increase in NTBs on EU trade with the UK has received little attention to date. In recent work, we assess the impact of NTBs (in the form of delays associated with border checks and documentary compliance) on Irish-UK trade (Byrne and Rice 2018). In this piece, we extend our analysis to other EU member states.

Non-tariff barriers: Impact channels

Border delays and NTBs have been shown to be a potentially larger barrier to trade than tariffs (Hummels 2007, Hummels and Schaur 2013). The importance of NTBs in the negotiations on the Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership and the EU-Canada Comprehensive Economic and Trade Agreement highlight their role as the most significant impediment to trade in developed markets with low tariffs.

NTBs reduce trade through two main channels. Firstly, they can increase the cost of doing business. NTBs that raise the cost of doing business may be quite specific – such as adherence to individual product standards – or more general, such as more stringent customs and documentary related procedures. Secondly, NTBs can restrict full access to markets (as in the case of quotas).

For EU member states conducting trade with the UK after Brexit, an increase in NTBs could reduce trade in two ways. First, outside of the customs union, British importers would be exempt from adherence to EU regulatory standards on goods imports from non-EU countries. This would harm the competitiveness of exporters selling EU-compliant goods to the UK market. Second, under any scenario, delays associated with increased customs handling times and documentary compliance requirements will exceed the current arrangement of frictionless trade and therefore increase costs for EU exporters. While the extent of checks at the UK border is not yet clear, the EU Union Customs Code sets out procedures required for EU exporters when exporting to a third country.1 These procedures include declarations at point of export, outward customs arrival, outward clearance, import, inward customs arrival, and where goods consignments must be held in temporary storage. In addition to this paperwork, goods are required to pass UK customs inspection procedures and are likely to be subject to additional handling delays due to the increase in volume of imports subject to such procedures.

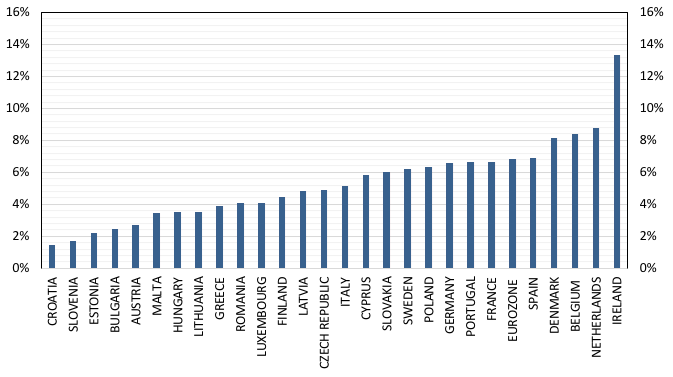

Figure 1 Share of exports to the UK (as a proportion of total goods exports)

Source: Eurostat

Effects of non-tariff barriers on trade with the UK

In Byrne and Rice (2018), we estimate the effect of potential increases in border delays and documentary compliance on trade between Ireland and the UK after Brexit. Here we extend that analysis to the rest of the EU. We measure NTBs using the sum of border waiting time and the time taken to complete all documentary compliance. These measures are taken from the ‘Trading Across Borders’ module of the World Bank’s Doing Business Survey.

Estimating the effect of potential increases in NTBs on trade requires two ingredients. First, we need the elasticity of trade to NTBs for high-income countries (both in aggregate and at the goods level). Second, we require an estimate for the likely increase in NTBs at the EU-UK border after Brexit.

To estimate the elasticity, we use a difference gravity model and a standardised measure of NTBs from the Doing Business survey. This model relates the volume of trade to the level of NTBs, controlling for distance, exchange rates, and other variables that traditionally determine the volume of trade. This methodology is similar to that which is used by Djankov et al. (2010).

Second, the estimate of the potential increase in border waiting times comes from a regression that assesses the impact on our NTB measure of doing trade with a country outside of one’s own free trade area, controlling for whether trade is carried out through a sea border, as well as income per capita and trade openness. This model suggests a 90% increase in NTBs for countries trading with the UK, compared with the status quo. We apply the elasticities from the first step to this predicted increase.

Of course, this is only an estimate of the likely increase in NTBs at the EU-UK border. In reality, the scale of the increase will be heterogeneous across countries and goods. However, our model gives us a framework to assess the impact of any given increase in NTBs.

We find a 9.6% decline in trade between Ireland and the UK, should the UK leave the Customs Union, as a direct result of an estimated increase in these delays. In particular:

- This equates to a 1.4% decline in total Irish exports and a 3.1% decline in total Irish imports under the current composition of trade between the two countries.

- Fresh foods, raw materials (such as metals and some intermediate inputs into firms’ supply chains), and bulky goods are most exposed to delays.

- Trade in petrol and other fuels, and chemicals and related goods do not appear exposed to delays.

Impact on EU member states' trade with the UK

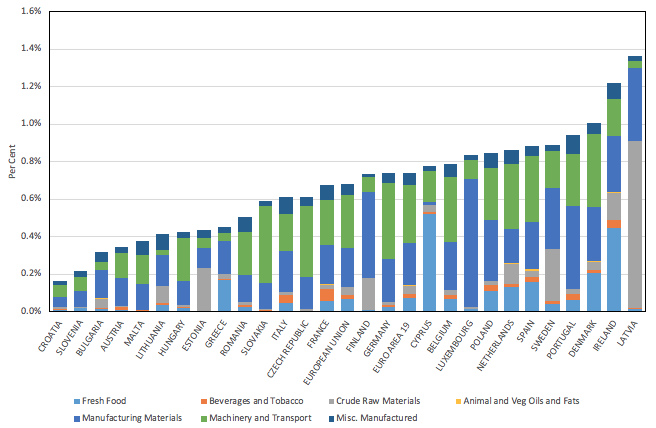

We apply our approach to exports by EU countries to the UK. The extent to which countries are affected by increases in NTBs after Brexit depends on the volume and type of goods they trade with the UK. Certain goods, such as non-perishable foods, are found to be unaffected by NTBs. Countries whose exports to the UK are comprised of a larger share of these goods will be less affected. Figure 2 presents the predicted declines in exports to the UK (as a fraction of total exports) at the goods-level for all EU countries, the EU, and the euro area.

Figure 2 Predicted decline in exports to the UK (percentage of total exports)

Source: Authors' calculations and Eurostat

Latvia appears most exposed to border delays due to its significant UK exports of Crude Raw Materials (in particular timber), goods that are highly sensitive to delays due to their role as intermediate inputs into supply chain networks and the fact that they are often perishable (Chen et al. 2018). The effect for Ireland is largely driven by its exports of fresh foods and manufacturing materials. Croatia and Slovenia appear least exposed. This is due to both the overall share of the UK market in their total exports (as shown in Figure 1) and the small quantity of their UK exports identified as being time-sensitive.

One drawback to our approach is that our static model does not allow us to explore potential second round effects. In particular, whether the decline in trade with the UK translates into aggregate trade losses depends on the degree to which countries are able to find new markets for their exports.

References

Byrne , S and J Rice (2018), “Non-tariff barriers and goods”, Central Bank of Ireland, Research Technical Papers 2018(7).

Chen, W, B Los, P McCann, R Ortega-Argiles, M Thissen and F van Oort (2018), “The continental divide? Economic exposure to Brexit in regions and countries on both sides of the Channel", Papers in Regional Science 97(1): 25–54.

Dhingra, S and T Sampson (2016), “UK-EU relations after Brexit: What is best for the UK economy?”,VoxEU.org, 6 August.

Djankov, S, C Freund and C S Pham (2010), “Trading on time”, Review of Economics and Statistics 92(1): 166–173.

Hummels, D (2007), “Transportation costs and international trade in the second era of globalization”, Journal of Economic Perspectives 21(3): 131–154.

Hummels, D and G Schaur (2013), “Time as a trade barrier”, American Economic Review 103(7): 2935–59.

Lawless, M and E L Morgenroth (2016), “The product and sector level impact of a hard Brexit across the EU”, ESRI Working paper, No 550.

Endnotes

[1] Regulation (EU) No 952/2013 of the European Parliament