The refugee crisis and the rise of anti-immigrant sentiments in most European countries has renewed interest in research on the impact of immigration on domestic economies. One set of policies that has not been widely investigated in the literature concerns the impact of legalisation policies, which apply to migrants who are already present and active in the native labour market and who, due to legislative constraints, are forced into the informal labour market, increasing the size of the shadow economy.

Many Western countries have planned and implemented massive regularisations of illegal migrants in recent decades (including the Border Security, Economic Opportunity, and Immigration Modernization Act of 2013 (S.744) in the US, the Zapatero Reform of 2006 in Spain, and Greek Law no. 2910/2001). A massive legalisation increases the labour supply for the formal labour market with (ex ante) ambiguous effects on native labour market outcomes, due for instance to complementarity/substitutability among heterogeneous labour inputs, endogenous technological change, and differences in task specialisation (e.g. Clemens et al. 2018, Ottaviano and Peri 2012, Lewis 2011, Peri and Sparber 2009). Therefore, it is crucial to estimate empirically the impact of legalisation policies on labour market outcomes.

In a recent study (Di Porto et al. 2018), we use individual-level administrative data to estimate the impact of a massive regularisation of undocumented migrants in Italy on labour market outcomes at the firm and individual levels, and on the career prospects of the newly legalised migrants.1

The framework of the regularisation policy

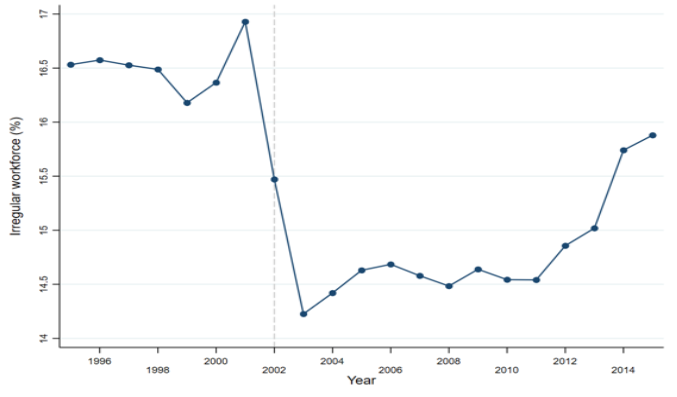

In 2002, the recently elected centre-right government led by Silvio Berlusconi reformed immigration laws through the so-called Bossi-Fini reform (Law 189/2002). As the reform was approved, the government decided to also include a massive regularisation of undocumented migrants already residing in Italy and (illegally) working. The objective of this policy was to provide incentives for firms and undocumented migrants to move from the informal to the formal labour market through the provision of work-residence permits. Law 189/2002 was approved in July 2002 but the regularisation for private employees was not introduced until the beginning of September 2002, ruling out any possible anticipation effect. The Bossi-Fini regularisation has been the largest in Italian history, with around 700,000 applications, and induced a sizeable drop (17%) in the rate of undeclared work between 2001 and 2003, in a country historically characterised by a large shadow economy (see Figure 1).

Figure 1 Irregular workforce in Italian labour market

Source: ISTAT data.

Note: The rate of undeclared work is computed as the percentage of units of undeclared work over total units of work.

To deal with a possible firm self-selection into the regularisation programme, we exploit an unexpected auditing programme (ex lege 383/2001), enforced around the time of implementation of the regularisation policy, as an exogenous variation for firm selection into treatment. This auditing programme was conceived the year before the regularisation, addressed a different segment of workers (irregular workers legally residing in Italy, hence excluding undocumented migrants), and was designed by different institutions with respect to the standard auditing activity. While the Social Security Institute is in charge of the regular auditing programmes at the national level, the ex lege 383/2001 inspections were jointly planned at the regional level by regional institutions, fiscal agencies, an inter-ministerial committee, and relevant ministries. We provide evidence that this unexpected auditing programme resulted in a quasi-random variation in the probability of inspection, exogenously increasing the expected fine related to the employer's labour tax evasion, and thus changing firms' willingness to take up the Bossi-Fini amnesty. We exploit the richness of our data and the specific features of the regularisation to identify a causal impact.

The impact of the regularisation policy

For our empirical analysis, we use recently available data issued by the Italian Social Security Institute (INPS) through the VisitINPS scholar programme. We merge the universe of firms in the private sector (excluding agriculture) with the universe of individual career histories over the last 30 years (roughly 15 million jobs per year). We add to this dataset the universe of firm-level audit programmes (more than 30,000 inspections per year).

We conduct three different levels of analysis.

- First, we investigate how the regularisation affected employment and wages of regularising firms.

- Second, we analyse the policy’s long-lasting effect in creating legal employment for the regularised migrants.

- Finally, as most of the economic and political debate is focused on the impact of such policies on workers’ careers, we explore the impact of the regularisation on the co-workers of regularised migrants, i.e. the group most exposed to the Bossi-Fini regularisation.

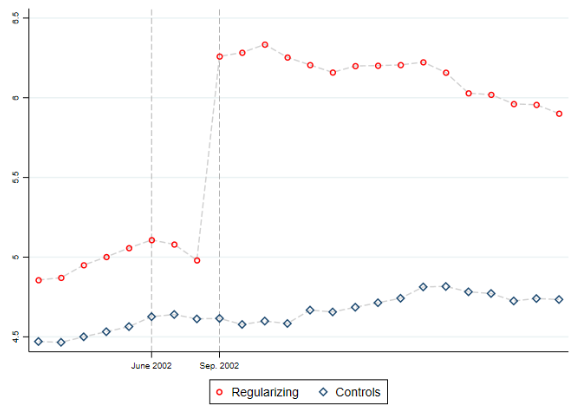

Figure 2 shows descriptive evidence of the trend in monthly employment at the firm level in the period around the regularisation. While the trend prior to September 2002 is similar for regularising and non-regularising firms, employment in the former group jumps significantly just after the introduction of the regularisation, and starts decreasing immediately after December 2002 (the end of the regularisation window). Moving to the rigorous econometric results at the firm level,2 we show that the regularisation has a positive causal impact on firm employment in the short run (May 2002 to December 2002), with an average increase of 2.6 workers per firm, but that the effect disappears in the medium run (May 2002 to May 2003) and long run (May 2002 to September 2003). We detect no significant causal impact on average wages nor on employment of native workers at the firm level.

Figure 2 Firm level employment, by month

Notes: The figure reports monthly employment for regularising and non-regularising firms. We include all firms that were active in 2002 and constituted before 2002 and we exclude the 99th percentile of firms in terms of employment in May 2002 and the firms in the 1st and 99th percentiles in the change in employment between May and December 2002.

The results from a firm-side policy perspective are rather disappointing – only a very short-lasting causal impact of regularisation, which dissipates after just one year of the policy. It could be argued that regularised workers go back to black, returning to the informal economy.

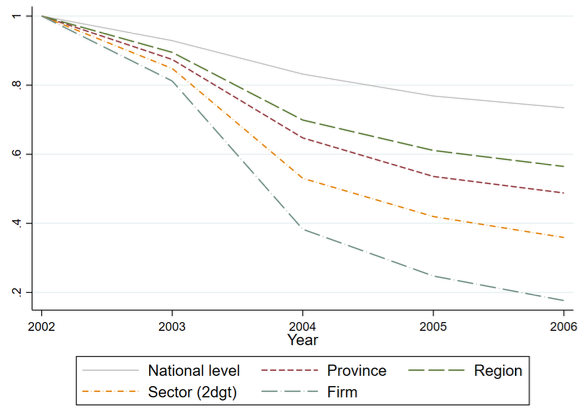

However, moving to the analysis of the careers of the regularised migrants, we find that their attachment to the formal labour market is surprisingly high (Figure 3) – around 75% of them are still legally employed in a private firm four years after the regularisation, although only 18% are still working in the same firm that regularised them and 38% in the same sector. Around half of the regularised migrants changed the province in which they work.

Figure 3 Probability of staying in employment for regularised migrant workers

Note: The figure shows the probability that the regularized worker remains employed in the private sector, in the same province, region, two-digit industry or firm where she was first hired, for each year after the regularisation.

In the third part of the analysis, we find that this attachment does not come at the expense of the migrants' co-workers, who experience neither higher job-separation rates nor longer spells of non-employment in the years after the regularisation.

In order to rationalise our findings, we explore the level of spatial and industrial mobility of regularised migrants compared to natives and previous migrant workers. We find convincing evidence that regularised migrants are far more mobile than native workers along many dimensions (firm, province, industry) – they are more than 35% more likely to change firm in the first years after entering the labour market, and 18% more likely to move to a different province. After getting a residence permit, this greater mobility allows newly legalised migrants to move within the territory and fill vacancies in different industries and provinces where the labour supply from (low-mobility) previous workers is scarce. These findings are in line with those of Cadena and Kovak (2016) for the US labour market.

Conclusions

In conclusion, we point out that the impact on employment at the firm level is transitory. However, the regularisation is likely to create long-term legal employment prospects for regularised migrant workers, who remain strongly attached to the formal labour market. They display high rates of industrial and local mobility, so that the increase in labour supply in the formal labour market does not increase the risk of job separation or unemployment for the previous workers that are more exposed to the regularisation. This shows that regularisation can be seen as similar to an active labour market policy for a specific group of workers – irregular migrants – pushing them to remain in the legal labour market with no effects on co-workers.

In periods of persistent mass migration resulting in increased numbers of illegal migrants in the population, as experienced by Italy and Europe as a whole in recent years, regularising undeclared migrant workers would appear to be a credible tool to increase social security payments and tax payments from workers who, if not regularised, would continue to work in the shadow economy.

References

Cadena, B C and B K Kovak (2016), “Immigrants equilibrate local labor markets: Evidence from the great recession”, American Economic Journal: Applied Economics 8(1):257-90.

Clemens, M A, E G Lewis and H M Postel (2018), “Immigration restrictions as active labor market policy: Evidence from the Mexican bracero exclusion”, American Economic Review 108(6):1468-87.

Di Porto, E, E M Martino, P Naticchioni (2018), “Back to Black? The Impact of Regularizing Migrant Workers”, WorkINPS Papers 2018(17).

Elias, F, J Monras and J Vàzquez Grenno (2018), “Understanding the Effects of Legalizing Undocumented Immigrants”, CEPR Discussion Paper 12726.

Lewis, E (2011), “Immigration, Skill Mix, and Capital Skill Complementarity”, The Quarterly Journal of Economics 126(2):1029-1069.

Ottaviano, G I P and G Peri (2012), “Rethinking The Effect Of Immigration On Wages”, Journal of the European Economic Association 10(1):152-197.

Peri, G and C Sparber (2009), “Task Specialization, Immigration, and Wages”, American Economic Journal: Applied Economics 1(3):135-169.

Endnotes

[1] Some recent papers carry out a similar analysis making use of aggregate data. For instance, Elias et al. (2018)investigate the effects of Spanish regularisation in 2006 making use of province-level data. They estimate that each newly legalised immigrant increased local social security revenues by an average of €4,189, with differential impacts on employment prospects of previous high-skilled and low-skilled workers (both native and immigrant) and with significant effects on internal migration.

[2] More specifically, we use an instrumental variable approach to investigate the impact of being a treated firm (i.e. of undertaking the amnesty) on employment and wages at the firm level. As an instrument we employ the exposure to the additional auditing programme in the same province and industry.