Editors' note: This column is part of the Vox debate on the economic consequences of war.

The Russia/Ukraine conflict has sent shockwaves throughout the world economy. Commodity prices, including energy, have increased sharply as uncertainty about supply disruptions has grown (Bachmann et al. 2022, Chepeliev et al. 2022). In addition, sanctions and trade restrictions have been imposed on Russian banks, businesses, and individuals (Berner et al. 2022). Finally, the conflict has sparked a massive refugee crisis, with over four million Ukrainians fleeing their country (at the time of writing).1 All of this is likely to contribute towards greater uncertainty in the economy, among businesses, households, and financial markets.

In this column, we present early evidence on the impact of the conflict in Ukraine on economic uncertainty using daily aggregate indices as well as firm-level measures from the Decision Maker Panel survey. Our focus is on forward-looking uncertainty measures that are available in near real-time. The war is likely to have increased economic uncertainty around both expected demand and inflation as well as creating concerns about supply chain disruptions.

Aggregate uncertainty measures

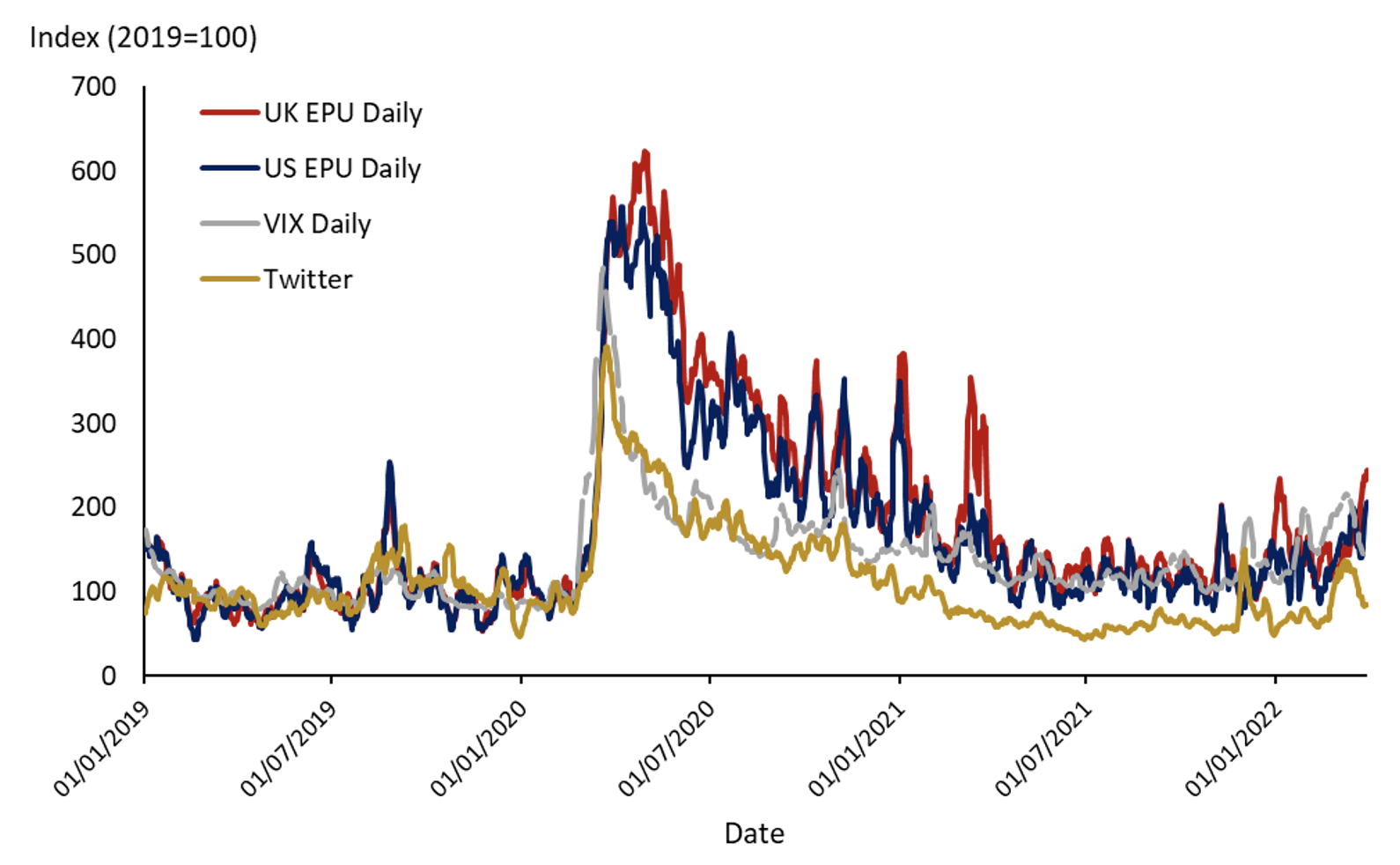

Indices based on financial markets and news/social media can provide information on economic uncertainty in close to real time. Figure 1 presents the evolution of four measures of economic uncertainty since 2019: the US Economic Policy Uncertainty (EPU) index, the UK EPU index, the VIX index, and a Twitter-based economic uncertainty index.2 All four measures are normalised by their respective average values in 2019 to ease comparison.

Although the series are noisy, all four metrics show that uncertainty increased after the Russian invasion of Ukraine in late February. The Vix and Twitter indices have since begun to fall back, but all series have recently reached their highest levels since the beginning of 2021, when the Delta variant of Covid-19 was spreading across the world. Nevertheless, current uncertainty is still below the peak observed in April 2020 by several orders of magnitude.

Figure 1 Daily uncertainty indices, January 2019 – March 2022

Firm-level uncertainty

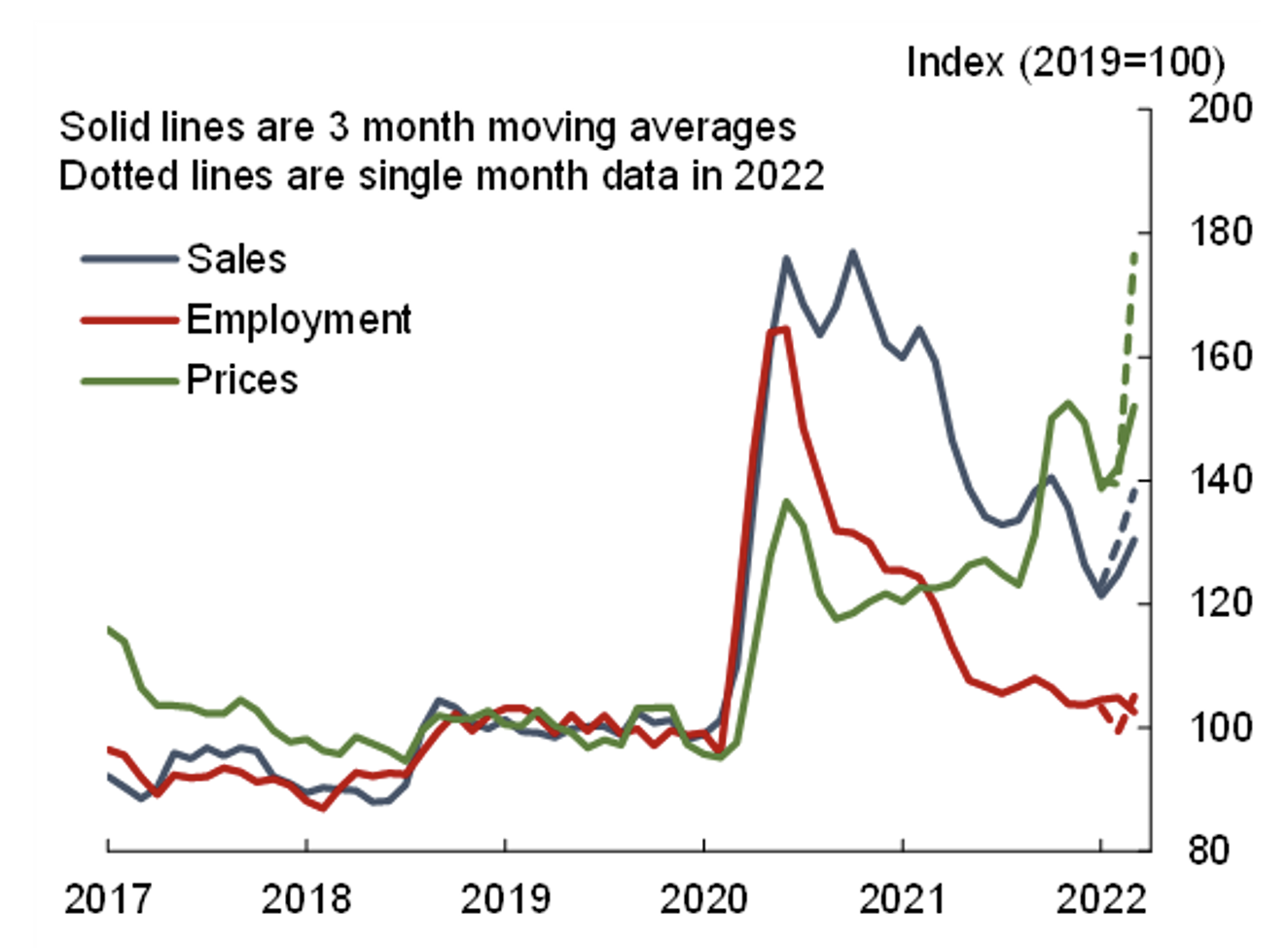

Another approach is to assess perceptions of uncertainty among firms. Focusing on the UK, we analyse the evolution of firm-level uncertainty using data from the Decision Maker Panel (DMP). The DMP is a representative monthly survey of chief executive officers and chief financial officers across the UK, with around 3,000 responses each month. It is used to study business trends across the country and to advise policymakers, including on the impacts of uncertainty around Brexit (Bloom et al. 2018, 2020) and Covid-19 (Altig et al. 2020, Bunn et al. 2021). Firms are asked about their realised and expected values for sales, employment, and prices. In addition, firms are asked about the distribution of expected outcomes. This allows us to calculate a standard deviation of expected year-ahead growth for each firm. We take the average across firms to construct measures of ‘subjective’ uncertainty for sales, prices, and employment.

The war in Ukraine has raised uncertainty about future sales and particularly inflation (Figure 2). Between January 2022 and March 2022, uncertainty about sales increased from just over 120% of its 2019 average to almost 140%. However, price uncertainty increased from 140% to around 175% in March 2022, its highest level since the DMP survey began in 2016. Meanwhile, employment uncertainty only increased modestly. This is a different pattern to that seen during Covid-19, and it highlights how uncertainty relating to the Ukraine war is particularly related to inflation, given the large associated movements in energy and other commodity prices.

Figure 2 Firm-level measures of subjective uncertainty

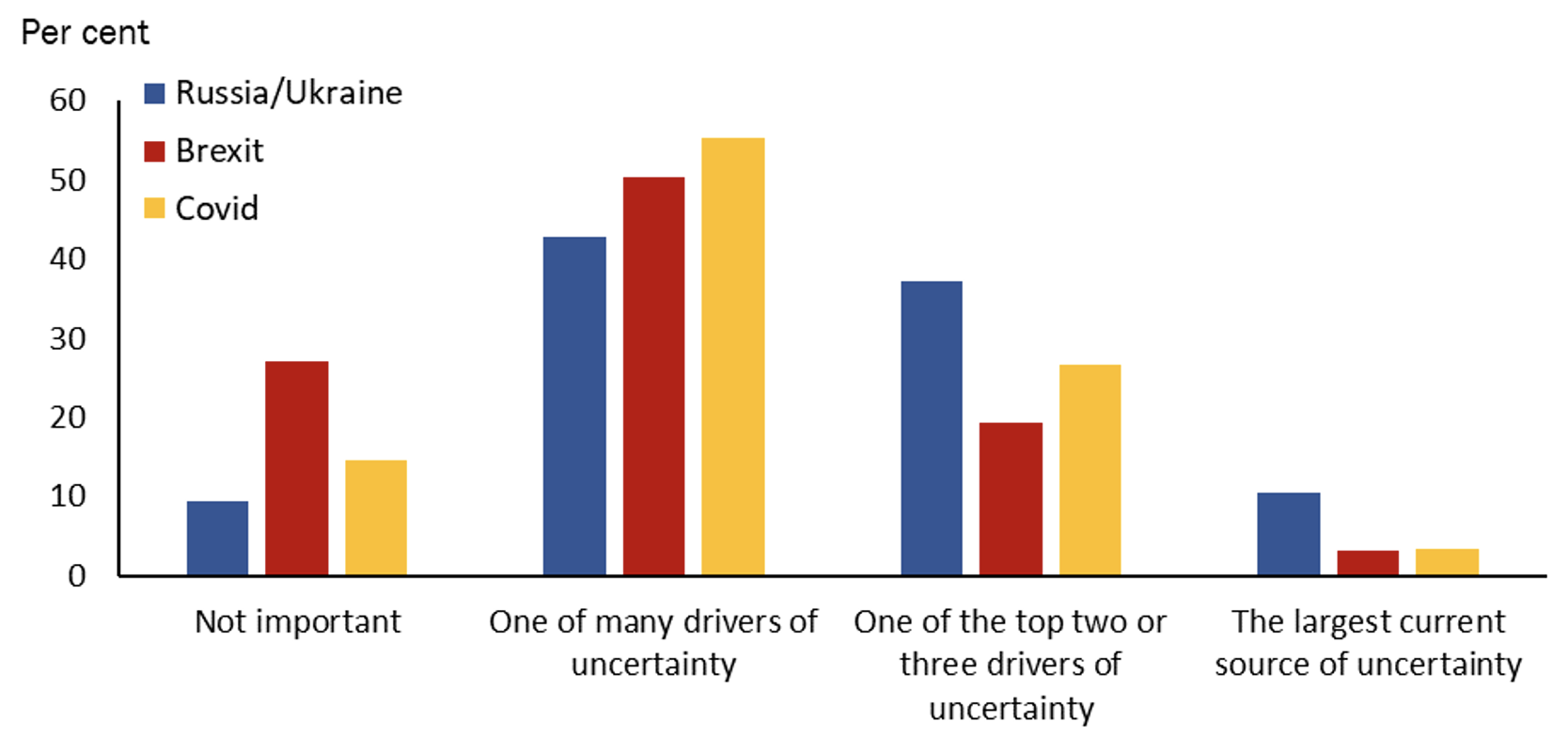

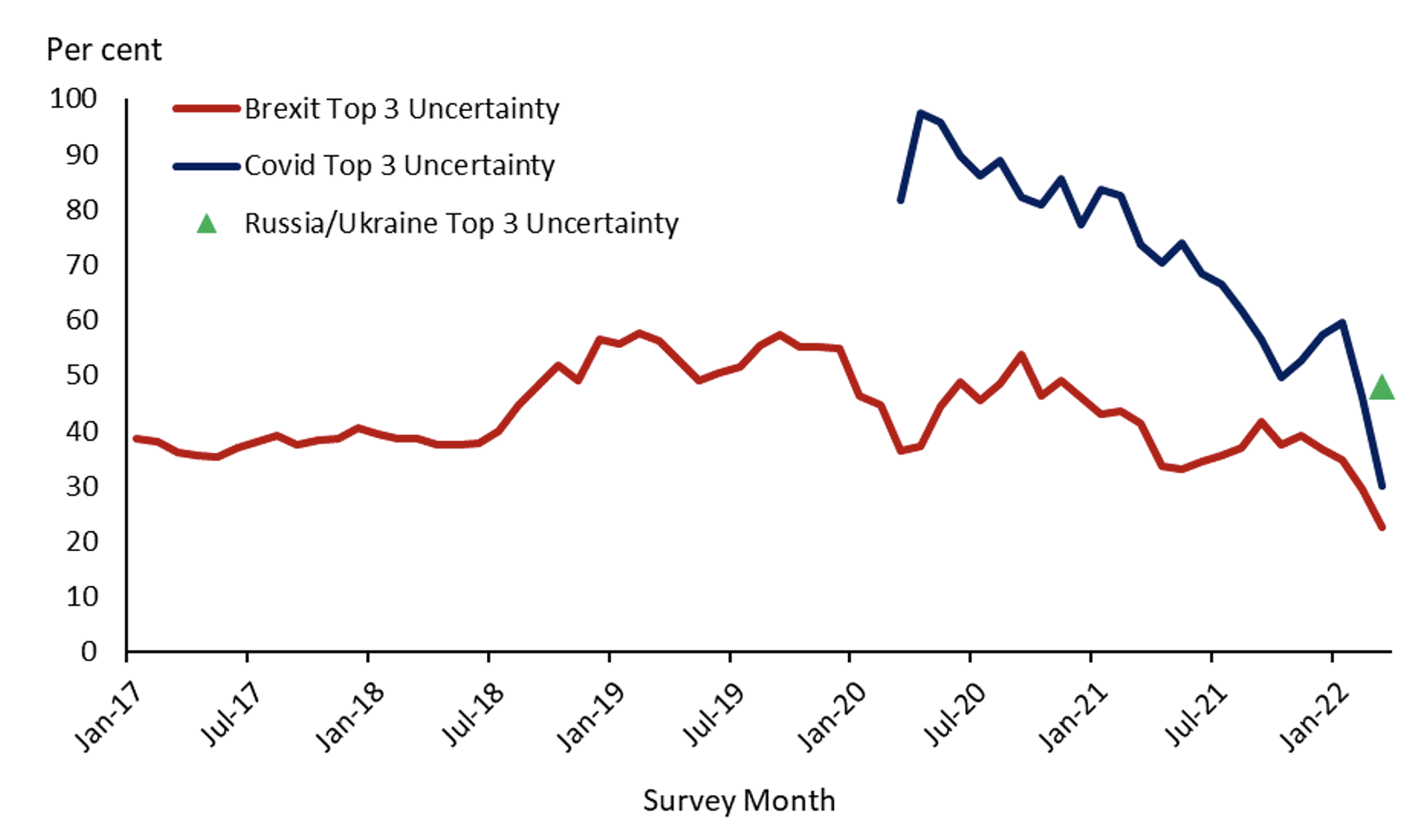

In addition to these subjective uncertainty indices, the DMP also asks about the importance of specific factors (e.g. Brexit, Covid-19) for business uncertainty. In March 2022, a new question was introduced asking about the Russia/Ukraine conflict as a source of uncertainty. Figure 3 shows the results, including a comparison to the relative importance of Brexit and Covid in the latest data. Of the three factors, the war in Ukraine was the largest source of uncertainty for UK firms in March: 48% of respondents considered the war as a top-three source of uncertainty, compared with 30% for Covid and 22% for Brexit. However, it is also important to put these numbers in context. Both Covid-19 and Brexit uncertainty have been on a downward trend in recent months (notwithstanding a small increase in Covid uncertainty due to the Omicron wave) (Figure 4). The current level of uncertainty regarding the conflict in Ukraine is below the peaks of Covid uncertainty (97% reported as a top-three source in April 2020) and Brexit uncertainty (57% reported as a top-three source in February 2019) seen in the past, supporting the evidence from aggregate trends presented in Figures 1 and 2.

Figure 3 Brexit, Covid-19, and Russia/Ukraine uncertainty, March 2022

Figure 4 Brexit, Covid-19, and Russia/Ukraine uncertainty

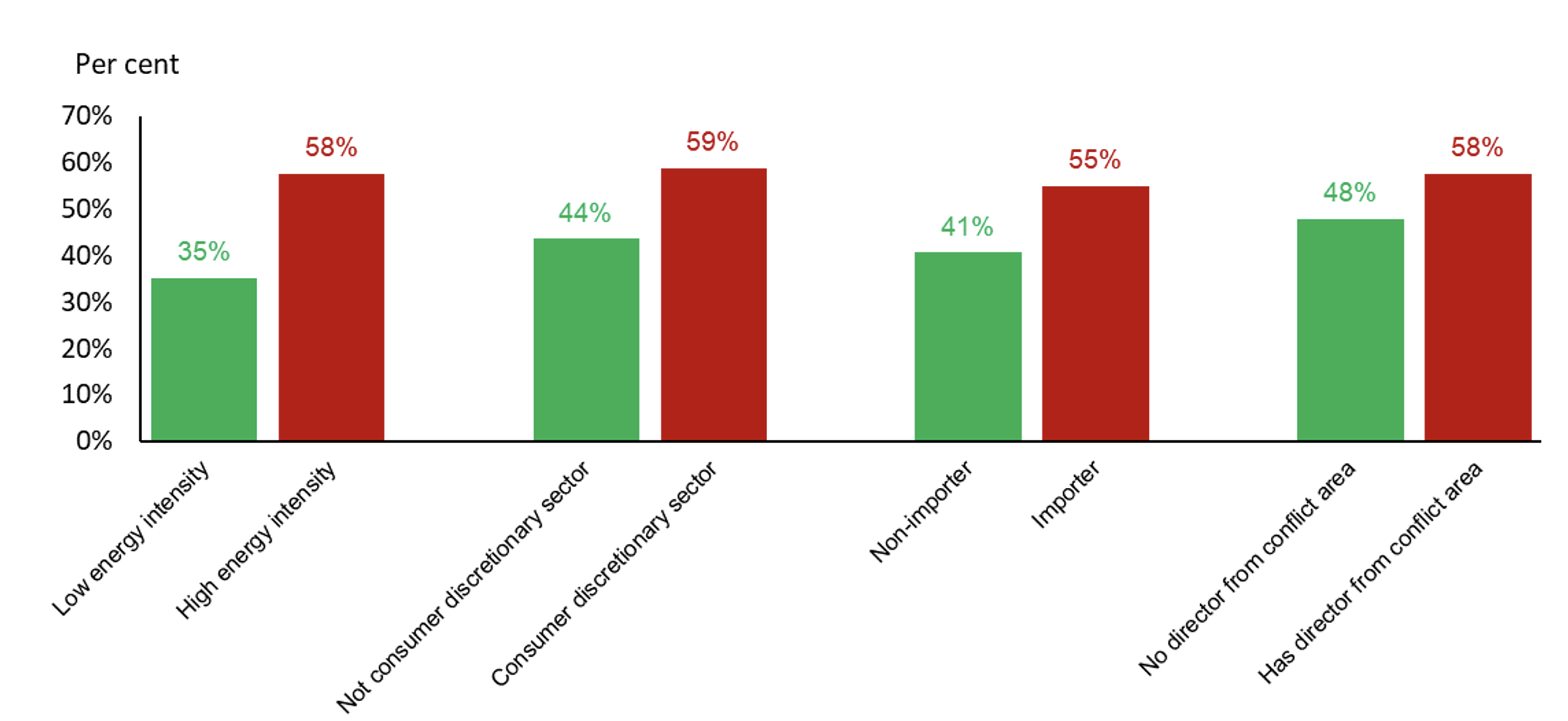

These relative levels of uncertainty may be driven by the heterogeneous nature of the Russia/Ukraine shock. For instance, firms in energy-intensive industries currently report higher uncertainty (Figure 5). Using data from the ONS Input-output supply and use tables,3 we find that 58% of firms in industries with above-average energy use reported that the Russia/Ukraine conflict was a top-three source of uncertainty, compared with only 35% of firms with below-average energy intensity. Second, firms in sectors oriented towards discretionary consumption (e.g. clothing, holidays, alcohol) reported higher uncertainty (59% versus 44%).4 Firms in more discretionary industries may be more concerned about the effects of a real incomes squeeze that leads consumers to focus more on essential expenditures. Likewise, importers are more likely to have reported the conflict as a top-three source of uncertainty compared with non-importers (55% versus 41%). These firms may expect to be more affected by supply disruptions, for example. Finally, we use company data from the Fame database to identify the nationality of directors across UK firms. There are around 1% of all UK firms that have at least one director from the conflict region.5 Matching this to the DMP dataset, we see that 58% of firms with a director from the conflict region reported the Russia/Ukraine conflict as a top-three source of uncertainty compared with 48% of firms without a director from the region.

In sum, these measures of exposure are neither mutually exclusive nor exhaustive, but they show that the conflict is affecting uncertainty for a range of UK businesses, and across a number of different channels: energy use, demand, trade, and ownership. Going forward, it will be important to monitor how business exposure to the conflict develops as well as the impacts on firm expected and realised outcomes.

Figure 5 Percentage of firms reporting Russia/Ukraine as a top three source of uncertainty

Conclusions

The war in Ukraine is already affecting the world economy. Daily measures of uncertainty have increased, but by much less than during the Covid pandemic. Measures of subjective uncertainty derived from firm surveys have also increased, particularly regarding inflation. Early evidence from the UK suggests that 48% of businesses considered the conflict a ‘top-three’ source of uncertainty in March, although that level is still below the peak uncertainty seen due to Covid-19 and Brexit in the past. Furthermore, this uncertainty is driven by multiple factors, including energy usage, import exposure, discretionary spending, and direct links of company directors to the conflict region. The implications of this uncertainty for businesses are still unclear, although the consequences of a protracted conflict will likely have adverse effects on multiple economic outcomes.

References

Altig, D E, S Baker, J M Barrero, N Bloom, P Bunn, S Chen, S Davis, J Leather, B Meyer, E Mihaylov, P Mizen, N Parker, T Renault, P Smietanka and G Thwaites (2020), “Economic uncertainty in the wake of the Covid-19 pandemic”, VoxEU.org, 24 July.

Bachmann, R, D Baqaee, C Bayer, M Kuhn, A Löschel, B Moll, A Peichl, K Pittel and M Schularick (2022), “What if Germany is cut off from Russian energy”, VoxEU.org, 25 March.

Berner, R, S Cecchetti and K Schoenholtz (2022), “Russian sanctions: Some questions and answers”, VoxEU.org, 21 March.

Bloom, N, S Chen and P Mizen (2018), “Rising Brexit uncertainty has reduced investment and employment”, VoxEU.org, 16 November.

Bloom, N, P Bunn, S Chen, P Mizen and P Smietanka (2020), “Brexit uncertainty has fallen since the UK general election”, VoxEU.org, 25 February.

Bunn, P, D E Altig, L Anayi, J M Barrero, N Bloom, S Davis, B Meyer, E Mihaylov, P Mizen and G Thwaites (2021), “Covid-19 uncertainty: A tale of two tails”, VoxEU.org, 16 November.

Chepeliev, M, T Hertel and D van der Mensbrugghe (2022), “Cutting Russia’s fossil fuel exports: Short-term pain for long-term gain”, VoxEU.org, 9 March.

Endnotes

1 Source: https://data2.unhcr.org/en/situations/ukraine

2 The US Economic Policy Uncertainty (EPU) index and the UK EPU index are two newspaper-based measures which count the number of occurrences of keywords related to (i) economy, (ii) policy, and (iii) uncertainty topics in major national newspapers. The VIX index is a measure of 30-day expected volatility of the US stock market based on option prices. Finally, the Twitter-based economic uncertainty index is based on the number of tweets mentioning both ‘economy’ and ‘uncertainty’ keywords. Sources: http://policyuncertainty.com/ and https://www.cboe.com/tradable_products/vix/vix_historical_data/

3 Source: https://www.ons.gov.uk/economy/nationalaccounts/supplyandusetables/datasets/inputoutputsupplyandusetables

4 The distinction between discretionary and non-discretionary industries is based on work done by the Australian Bureau of Statistics, which provide a classification for separating goods/services in the CPI inflation basket into those of a discretionary (i.e. essential) and non-discretionary (i.e. optional) nature. The classification can be accessed here. The same classification has been used by the Office for National Statistics in the UK.

5 The ‘conflict region’ is defined as Russia, Ukraine, Belarus, as well as Poland, Hungary, Slovakia, Moldova, and Romania. There are approximately 164,000 UK firms that have at least one director from the conflict region. Around 1% of our sample with responses to this question has a director from the conflict region, matching the statistic for the universe of UK firms.