According to the World Bank (2020), as much as 50% of world trade involves global value chains (GVCs). GVCs have been constructed by multinational corporations, as they fragment production processes into various tasks and base them in various countries/locations, where particular tasks can be conducted most efficiently, to achieve efficient production systems, through foreign direct investment. As the importance of GVCs in international economic activities increases, policymakers and researchers have been paying attention to GVCs as a driving force for further economic growth and attempting to develop policies to engage domestic firms in GVCs. These interests are based on the experience gained from the cases of numerous firms experiencing productivity improvements after GVC participation and the theoretical background that GVC participation can benefit the firms and countries participating in GVCs (Li and Liu 2014, Baldwin and Robert-Nicoud 2014).

Many empirical studies have been conducted to examine the productivity-enhancing effect of GVCs. They are largely divided into macro-level studies at the industry level and micro-level studies at the firm level. Macro-level empirical studies using trade data or international input-output tables generally find productivity-enhancing effects of GVCs, but macro-level analysis does not include firm heterogeneity in the analysis, so it is unclear through what channels firm productivity increases. Contrary to macro-level studies, micro-level studies have the advantage of including firm heterogeneity in the analysis to identifty the channels of productivity increase. Micro-level studies have begun recently as necessary data became available, but the number of studies on the impact of GVCs on productivity is very limited.

Defining a GVC firm as a firm that exports and imports simultaneously, we examined if GVC participation improved the productivity of Japanese firms by using the firm-level data covering approximately 10,000 firms for the 1994-2018 period. To verify this hypothesis, we used the propensity score matching (PSM) method to identify the selection effect (whether high productivity firms participate in GVCs), and the difference-in-differences method to examine the learning effect (whether participation in GVCs increases productivity). Simply testing if GVC firms exhibit higher productivity than non-GVC firms does not reveal the impact of GVC participation on productivity, because it is not known if a firm is a new GVC participant or a continued participant. Needless to say, we are interested in new GVC participants. To identify new participants, the GVC status of a firm in the previous period must be ascertained. To test the effect, we compare productivity of new GVC firms with non-GVC firms with similar characteristics in the previous period. The propensity score matching method is useful in identifying those non-GVC firms with which GVC firms are appropriately compared for the productivity-enhancing effect of GVCs.

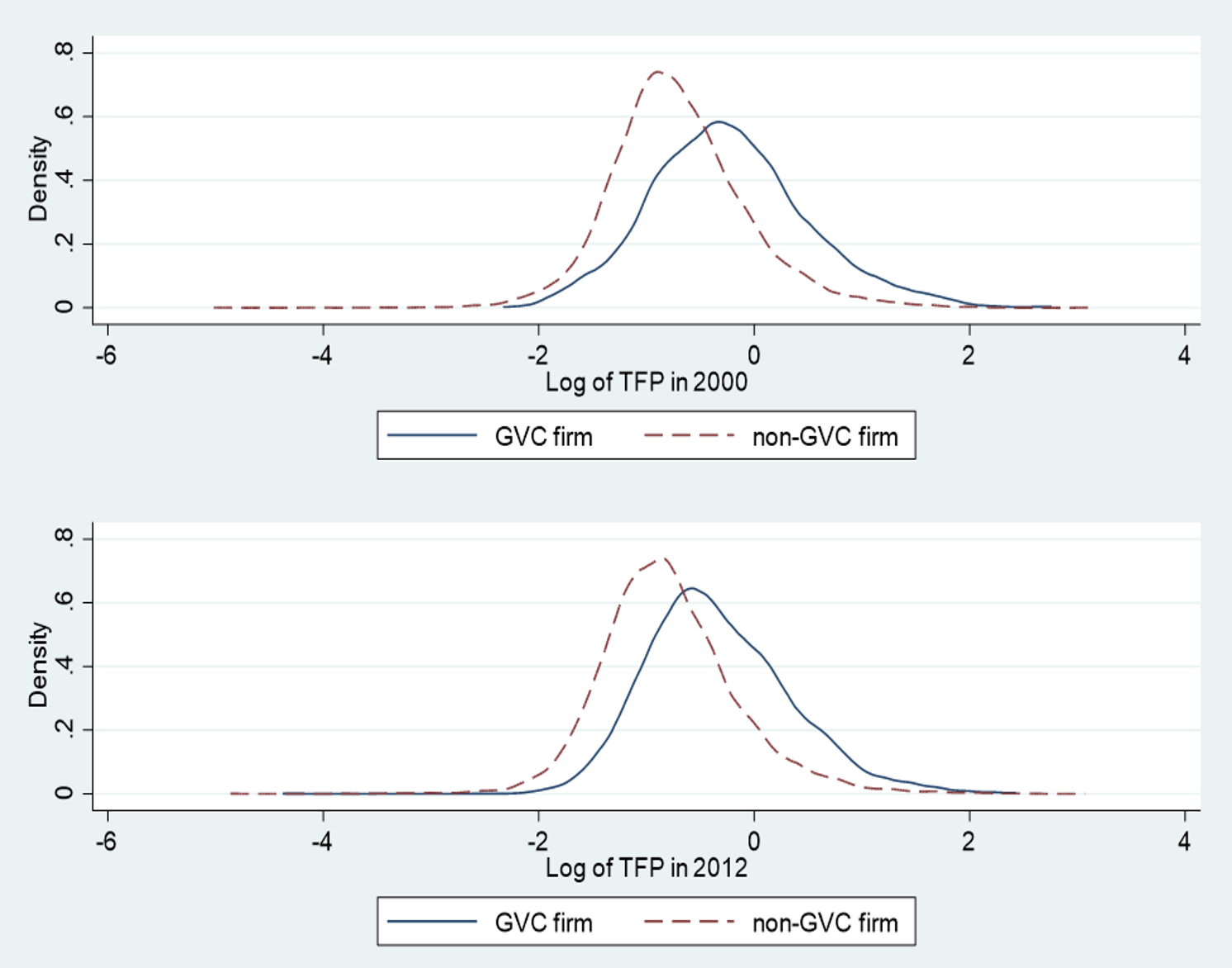

Our findings can be summarised as follows: There are significant variations in total factor productivity (TFP) among GVC firms and among non-GVC firms, as shown in Figure 1. On average, GVC firms exhibit higher producitity compared to non-GVC firms, but there are a number of non-GVC firms that register high productivity. Wakasugi et al. (2008) found a similar pattern between exporting and non-exporting firms in the Japanese manufacturing sector.

To test the importance of experience in GVC participation on productivity (learning effect), we estimated the impact of GVC participaton on producvity not only for the first year of GVC participation but also for the subsequent five years. Our analysis showed the impact of GVC participation on productivity (learning effect) is positive for nearly all of the 110 estimations with few exceptions, and the estimated coefficients are statistically significant for approximately 35% of the cases. These findings indicate that the impact of GVC participation on productivity for Japanese manufacturing firms is generally positive, but the impact is not very strong. We also found that the magnitude of the positive coefficient increased over time, indicating that it takes GVC participating firms time and the accumulation of experience to assimilate new technology and the management know-how they acquired through GVC participation.

Figure 1 Total factor productivity distribution by GVC participation

Source: Urata and Baek (2022). Our computation is based on the Basic Survey of Japanese Business Structure and Activities (METI).

We draw several policy implications from the empirical results. First, recognising the importance of having high productivity for a firm to participate in GVCs, which we have determined is a potential source of further productivity improvement, the government should provide technical assistance such as training courses and R&D support to firms with such potential, in addition to setting up a conducive environment for technical progress by protecting intellectual property rights and ensuring competition. Second, the government should provide non-GVC firms with support for participating in GVCs. As shown above, there are many Japanese firms with high productivity that do not participate in GVCs, largely because of the high cost and risk associated with GVC participation. The government should implement measures to lower such costs and risks. For example, marketing assistance such as dissemination of market information pertaining to foreign countries would allow non-GVC firms to begin to participate in GVCs. Furthermore, trade liberalisation and facilitation would facilitate non-GVC firms to participate in GVCs. Specifically, the government should actively establish free trade agreements (FTAs), which include trade liberalisation and facilitation. Free trade agreements would lower or eliminate tariffs, promoting imports and exports. Trade facilitation in various forms, including improving customs procedures and simplifying the rules of origin, would also help lower the barriers to trade and promote GVC participation.

Author’s note: The main research on which this column is based (Urata and Baek 2022) first appeared as a Discussion Paper of the Research Institute of Economy, Trade and Industry (RIETI) of Japan.

References

Baldwin, R and F Robert-Nicoud (2014), “Trade-in-Goods and Trade-in-Tasks: An Integrating Framework”, Journal of International Economics 92(1): 51–62.

Li, B G and Y Liu (2014), “Moving up the Value Chain”, mimeo, Boston University.

Urata, S and Y Baek (2022), “Impacts of Firm GVC Participation on Productivity: A Case of Japanese Firms”, Research Institute of Economy, Trade and Industry (RIETI), RIETI Discussion Paper Series 22-E-021.

Wakasugi, R, Y Todo, H Sato, S Nishioka, T Matsuura, B Ito and A Tanaka (2008), “The Internationalization of Japanese Firms: New Findings Based on Firm-level Data”, Research Institute of Economy, Trade and Industry (RIETI), RIETI Discussion Paper 08-E-036.

World Bank (2020), World Development Report 2020: Trading for Development in the Age of Global Value Chains, The World Bank.