The payment landscape is changing. Rapidly. More payment operators are non-banks who propose e-solutions to make payments both online and in real life. Some are big players, such as the ‘Big Four’ tech companies, and others are much smaller start-ups (Committee on Payments and Market Infrastructures 2015). These changes are creating a more decentralised payment landscape, qualified by some as a revolution in payments (Coeuré 2019, Mersch 2019).

Technologies have changed, but the pattern looks strikingly familiar to the students of European monetary history. To them, there is no natural law tying the payment instruments with their operation by the banking system. From the Middle Ages to WWI, the most common payment instrument outside coins and banknotes was operated by both banks and non-banks (Van der Wee 1977). Similarly, banks and non-banks alike will operate e-payments. This makes history an interesting source of inspiration to search for institutional solutions in order to fix the impact of the payment revolution on financial instability caused by a lack of access to emergency liquidity assistance.

In recent work (Avaro and Bignon 2019), we explore the implications of this more decentralised and less banked payment landscape for the design of central banks’ interventions when fighting financial crises. We take the example of the Banque de France because Bignon and Flandreau (2018) show that it was especially successful in taming financial and banking panics. We add that this was achieved in a situation of significantly unbanked payments in which non-banks represented half of the borrowers at the Banque de France discount window.

Payment instruments, non-banks, and financial stability

One of the most radical transformations is observed in China, where payments with mobile phones using Quick Response code systems operated by new fintech giants Alipay and WeChat Pay reached $41 trillion in 2017 (e.g. Klein 2019). The number of Chinese merchants refusing cash is taking off, forcing the People’s Bank of China to issue a formal notice stating that renminbi cash is legal tender. In India, where the yearly digital payment flows are expected to reach $1 trillion in a decade, the competition is raging among local start-ups and fintech giants. Outside Asian markets, the big tech players are also investing massively in digital payment technologies – Facebook and Telegram are running a close race to issue their own digital payment solutions.

Yet payment operators can fail when they do not have the liquidity required to meet payment ends. In such a case, users of those payment instruments will be unable to use them to pay, thus spreading the liquidity stress across the payment system. This was not a big deal in the 20th century during which payments were traditionally operated by banks. The institutional fix was the lender-of-last-resort lending by a central bank (sometimes called the ‘discount window’). When injecting liquidity, a central bank swaps money against illiquid means of payments, thus cooling down financial stress, and reducing the number of fire sales and failures, and the interest rate at which people borrow.

The new solutions for digital payments are challenging this model. The new operators are outside the traditional scope of intervention of central banks, as a central bank is the bank of the other banks and not the bank of all payment operators. This is directly influencing the ability of central banks to fulfil their mandate of financial stability.

History can help us to think about solutions fit for the new system. Before 1914, the central bank opened up access to the central bank discount window to all payment operators, in an effort to limit the systemic cost related to the default of non-banks. This facility was widely used. Many companies had secured access to the discount window, with about 5% of French companies eligible in 1898. Yet allowing access did not mean that everybody used it. In 1898, 0.05% of non-bank companies had effectively used it, which compares to 27% of banks which did.

Width of the discount window and the moral hazard issue

Theory suggests that operating a widely accessible discount window may expose the central bank to greater risks (Jensen and Meckling 1976, Rochet and Tirole 1996). The certainty of the access to the discount window may bring issues of moral hazard and induce financial intermediaries to increase their exposure to credit risk in the hope of selling the risky assets to the central bank when the crisis comes, in a mechanism akin to a risk-shifting strategy.

Yet the Banque de France was a very profitable central bank, suggesting that something prevented the theoretical fantasy to materialise. As suggested by theory, three mechanisms were effective in mitigating agency issues arising from the operation of a wide discount window:

- the pledging of collateral that was seized in case of default;

- the screening and monitoring of the risk appetite of the borrowers, and its use in the central bank decision to lend; and

- the use of some form of relationship lending by which the Bank tends to reward the building of a long-term reputation by the use of the discount window.

The screening of risk appetite by the Banque de France follows a review process similar to what rating agencies are doing today. It consists of an analysis of the risk culture, the credit risk and the internal governance of the entity. The central bank acquires and processes proprietary soft information to grade risk appetite and uses it to discriminate against different types of counterparties. Very few non-banks were rated as risk-takers. With banks, the Banque de France uses its risk assessment to prioritise lending to risk averse counterparties, in a mechanism akin to the use of haircuts that differs depending on the ratings of the financial assets.

Cooling down stress in crisis times

The central bank used all those risk management tools when it had to extend its discount operations to smooth negative local economic shocks. This was true both at the intensive and extensive margin. To show this, we study how crisis stress – such as the war in Cuba between Spain and the US, a cattle disease, or a bank run – impacted the discount activity in the 20 regional economies.

In crisis times, the Banque de France increases its liquidity support more to risk averse agents and to agents that had the ability to pledge more collateral. During a crisis, the central bank values more relationship lending and discounts with agents who had already used the discount window a year before. The rationale is that the Banque de France had accumulated a backlog of information on them, most often because they use the discount window to transfer funds within France through the national payment system operated by the central bank.

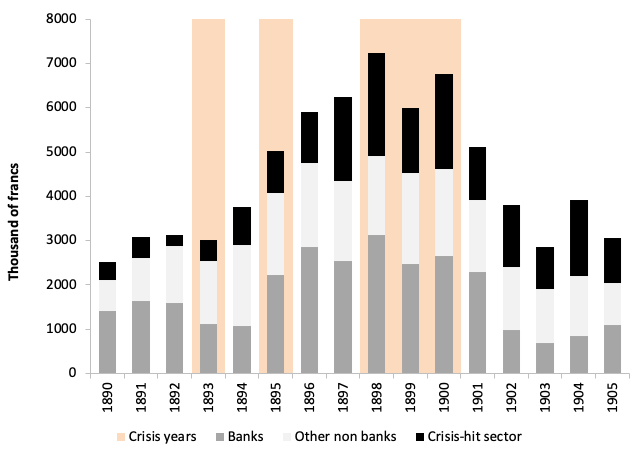

Crises also bring new users to the discount window. In regional economies hit by a crisis, most newcomers to the discount window were non-banks. The region around Moulins in the centre of France – where young calves were fed to grow – exemplifies the case. Two droughts and a cattle disease had put a strain on the farmers. With the unfolding of the financial distress, the discount activity with banks had increased significantly, but a notable development was the discount to the landlords of grass fields who increased credit to their clients, the cattle farmers (see Figure 1).

Figure 1 Volume of liquidity provided by the Bank of France in Moulins, 1890-1905, by category of presenters

Source: Archives of the Banque de France, Banque de France supervisory report of Moulins (1890-1905).

Reading: In 1898, Banque de France counterparties borrowed 3,120, 000 francs, the suppliers of the crisis-hit sector borrowed 2,320,000 francs and the other non-bank counterparties received 1,800,000 francs.

Note: The category crisis-hit sector features mostly local landlords and some cattle farmers whose activity was hit by weather shocks and a cattle disease. ‘Other non-banks’ includes non-banks whose activity was not directly impacted by the crises. Shaded columns represent crisis years (weather shocks and a cattle disease).

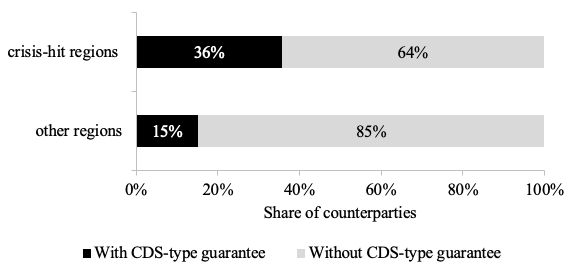

To make sure that access to the discount was effectively opened to a diverse set of counterparties, the Banque de France accepted a broad and diverse set of guarantees to the discount operations. On top of marketable securities, it also accepted credit default swap-type instruments such as sureties, a special contractual form whereby the issuer promised to pay in lieu of the debtor in case of a failure. Figure 2 shows that this was especially useful in crisis-hit regions where the proportion of discount operations guaranteed by credit default swap-type guarantees was more than twice the level of that in non-crisis regions.

Figure 2 Use of credit-default-swap type of guarantees among counterparties in districts hit or not hit by a crisis

Source: Archives of the Banque de France, rapports d’inspection 1898.

Reading: In 1898, 36% of counterparties from the regions hit by a crisis pledged a credit-default-swap type of guarantee.

Note: The category ‘crisis’ groups 20 regions – out of 94 – that were hit by an economic crisis triggered either by trade reduction caused by the Spanish-US war of 1898, by an agricultural disease or by a bank run.

Finally, our study indicates that the Banque de France made special use of its screening of risk appetite in distressed times. At the same time, new non-bank counterparties increased their probability of accessing the discount window in crisis times if the central bank deemed them to be risk averse.

Although operating this risk management framework requires a lot of information gathering by front, middle, and back offices, it is worth noticing that the Banque de France did not lose money in crisis-hit regions despite an increased discount activity and a more diverse set of counterparties. This illustrates how the central bank mastered the risk-taking channel of a wide discount window by adopting the right set of risk management tools, thus endowing it with a tool which was efficient in reducing payment system stress.

Conclusion: Lessons from the history of the Banque de France

With the ongoing change in day-to-day payment habits towards more digital and unbanked solutions, central banks are not without weapons. They can turn to their own history to adapt their refinancing policy to the new environment. This may help them to adapt their toolkit to address potential additional risk to financial stability without requiring them to increase their risk load.

References

Avaro, M and V Bignon (2019), “At your service! Liquidity provision and risk management in 19th century France”, CEPR Discussion Paper 13556.

Bignon, V and M Flandreau (2018), “The other way: A narrative history of the Bank of France”, in Edvinsson, R, T Jacobson and D Waldenström (eds), Sveriges Riksbank and the History of Central Banking, Cambridge University Press, pp. 206-241.

Cœuré, B (2019), “Fintech for the people”, keynote speech at the 14th BCBS-FSI high-level meeting for Africa, 31 January.

Jensen, M C and W H Meckling (1976), “Theory of the firm: Managerial behavior, agency costs and ownership structure”, Journal of Financial Economics 3(4): 305-360.

Jia, Y and G Wildau (2019), “Chinese merchants refuse cash as mobile payments take off”, Financial Times, 1 January.

Klein, A (2019), Is China’s new payment system the future?, Brooking Economic Studies report.

Mersch, Y (2019), “Promoting innovation and integration in retail payments to achieve tangible benefits for people and businesses”, speech at the American European Community Association, 7 February.

Mundy, S (2018), “India’s paytm comes under pressure from Silicon valley rivals”, Financial Times, 3 June .

Popper, N and M Isaac (2019), “Facebook and telegram are hoping to succeed where bitcoin failed”, New York Times, 28 February.

Rochet, J-C and J Tirole (1996), “Interbank lending and systemic risk”, Journal of Money, Credit and Banking 28 (4): 733-762.

Committee on Payments and Market Infrastructures (2015), “Digital currencies”, Bank for International Settlements, 23 November.

Van der Wee, H (1977), “Monetary, credit and banking systems”, in Rich, E and C Wilson (eds), The Cambridge economic history of Europe, volume 4, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 290-392.