What explains global inflation? Despite a large empirical literature on this subject, open questions remain (Ehrmann et al. 2020). No single approach has been able to explain persuasively how inflation evolves. From a variety of potential determinants, the literature has broadly highlighted economic, institutional, technological, and political factors, which we group into eight economic theories: (1) natural resources, (2) demography, (3) globalisation and technology, (4) money, credit, and slack, (5) monetary policy strategies, (6) political and institutional setup, (7) public finances, (8) past inflation.

Overall, this literature has put forward mixed results. However, studies are often framed in a cross-section of low-inflation countries over relatively short time periods and centred on a limited number of predictors. From a methodical point of view, the focus has been on linear relationships, although linearity cannot be taken for granted, and only few robustness checks based on alternative estimation techniques or model comparisons are provided.

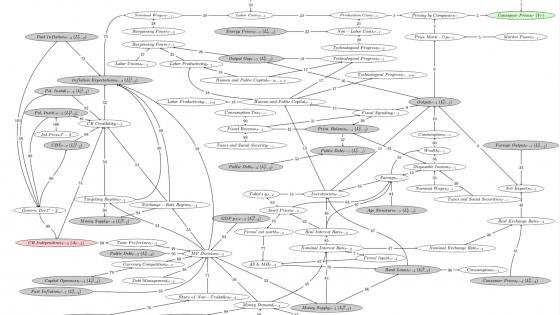

This is the motivation for a recent study (Baumann et al. 2021a) in which we estimate and compare the main driving forces of global inflation, evaluate models motivated by economic theory against a machine-learning-based approach, account explicitly for non-linearities, and examine structural breaks. For this purpose we recurred to additive mixed models (AMMs) selected by conditional Akaike information criteria. AMMs are a regression technique that has been widely used in other areas of research like epidemiology, for example, but not to study inflation.

The results presented below are obtained from the estimation of 98 AMMs based on 37 exogenous variables across 122 countries, including advanced, emerging, developing, and low-income markets over the period from 1997 to 2015. We assigned the corresponding exogenous variables to the eight economic theories mentioned above and compared them to an AMM whose variables were selected by a machine-learning algorithm, specifically, model-based boosting.

Results

1) Energy prices and rents

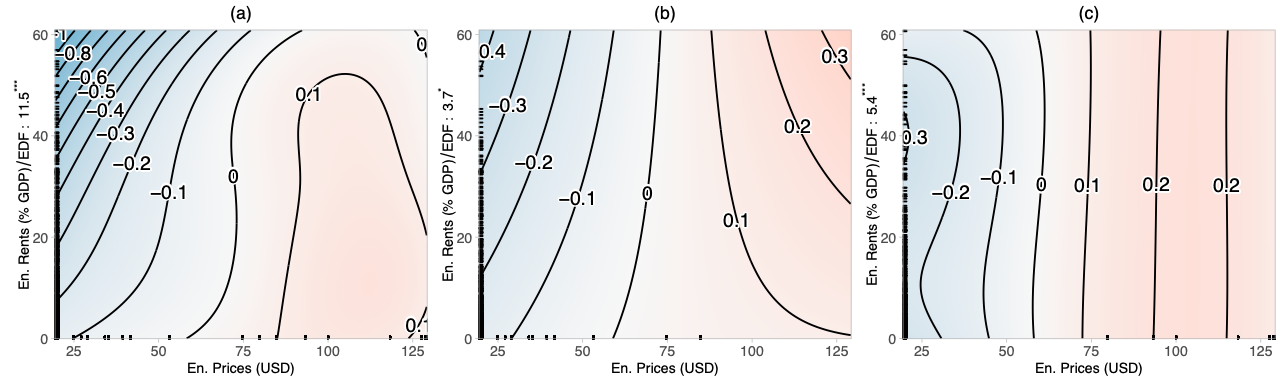

What matters most for inflation is the interaction of energy prices (mainly oil) with energy rents rather than energy prices on their own. Figure 1 summarises the evidence using contour plots. The passage from a blue to a red area indicates mounting inflationary pressure, while the passage from a red to a blue area suggests the opposite. The black contour lines serve as guidance for the strength of effects. Panel (a) covers the entire period of observations, panel (b) the period preceding the Global Crisis, and panel (c) the years since then. As exhibited in panel (a), the strongest inflation-boosting effect arises when energy prices are low and energy rents are high (upper left-hand corner). In this setting, an increase in energy prices results in a strong acceleration of inflation, which holds up to a level of about $90. In contrast, when energy rents are low, rising energy prices still increase inflation but not as strongly as when rents are high. Beyond $80, this effect levels off. Comparing panel (b) with panel (c) suggests that this interplay has weakened since the Global Crisis.

Figure 1 The bivariate interaction of energy prices (US $) and energy rents (% GDP) illustrates that its effect on log inflation is not linear

Note: Interpretation of the contour lines is only relative and not absolute with respect to log inflation.

2) Demography, technological progress, and globalisation

The ageing of society is often mentioned in the literature and media reports as a factor bearing on inflation. Empirical studies have come up with diverging results. We found that the demographic trends have contributed to the disinflation trend outlined above, although they were less relevant than the interplay between energy prices and rents. A rise in the share of information and communication technology (ICT) capital increases inflation and outperforms globalisation proxies, such as countries’ trade and financial openness.

3) Money and credit growth

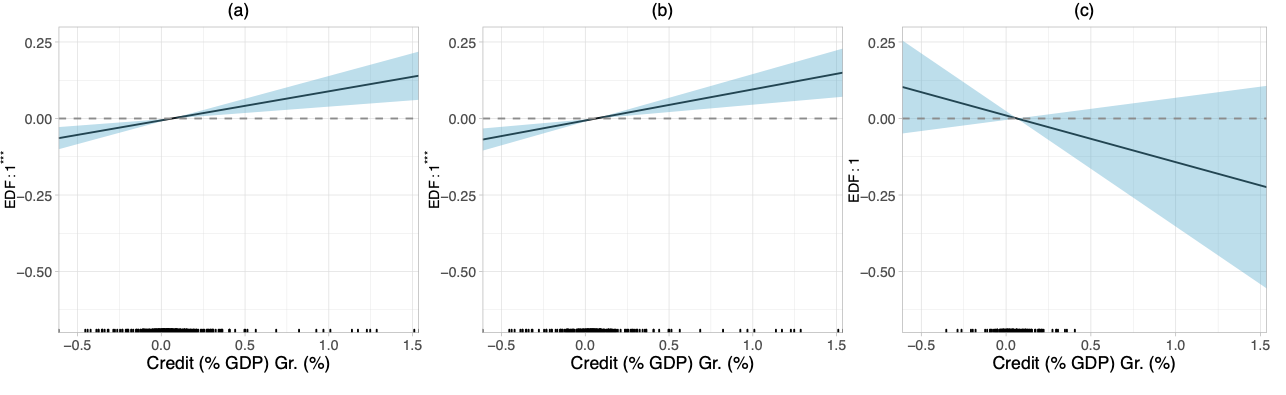

Overall, money growth (M2) is less relevant than credit growth. While credit creation over the whole sample period is linearly related with inflation (Figure 2, panel a), this pattern appears to have weakened or even turned negative after the Global Crisis (panel c). In contrast, the positive link of M2 growth with inflation has remained nearly constant.

Figure 2 Linear effect of credit (% GDP) growth (%) on log inflation, across the entire time period (panel a), before the crisis (panel b) and after the crisis (panel c)

Note: Interpretation of the y-axis is only relative with respect to log inflation.

4) Monetary policy and political setup

According to Milton Friedman (1974: 1), "[t]here is no technical problem about how to end inflation. The real obstacles are political." Thus, in addition to demographic and macroeconomic variables we also considered countries’ political setup and accounted for monetary policy strategies, central bank independence, and transparency. Their explanatory power is low, however. From several political variables only civil liberties, whose expansion has been disinflationary after the crisis, are relevant.

5) Public finances

The effects of public deficits and debt on inflation is a topic that has generated considerable interest and debate among economists and politicians. There are two views on this issue. Milton Friedman (1970: 11) asserted that fiscal policy by itself is not important for inflation, whereas for Thomas Sargent (2013: 213) “[p]ersistent high inflation is always and everywhere a fiscal phenomenon.”

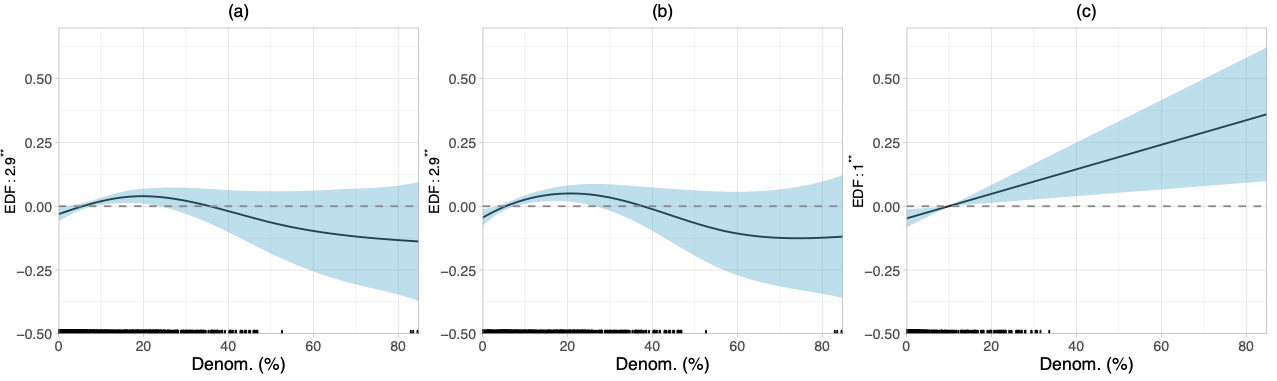

Despite a vast literature suggesting otherwise, our results indicate that public debt has been no major source of inflation. More relevant is its management, in particular the share of external debt denominated in a foreign currency (Figure 3).

Figure 3 Effect of denomination (%) on log inflation across the entire time period (panel a), before the crisis (panel b) and after the crisis (panel c)

Note: Interpretation of the y-axis is only relative with respect to log inflation.

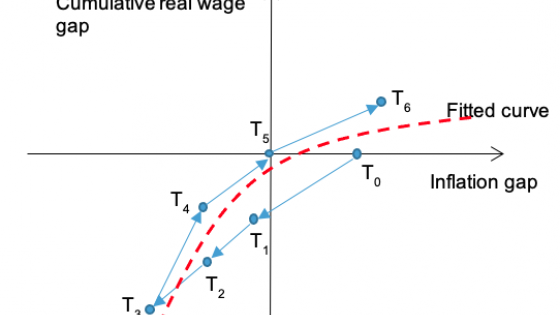

6) Past inflation

Current inflation is influenced positively and linearly by past inflation, suggesting the existence of ‘adaptive expectations users’, who use past inflation to forecast future inflation.

7) The real side

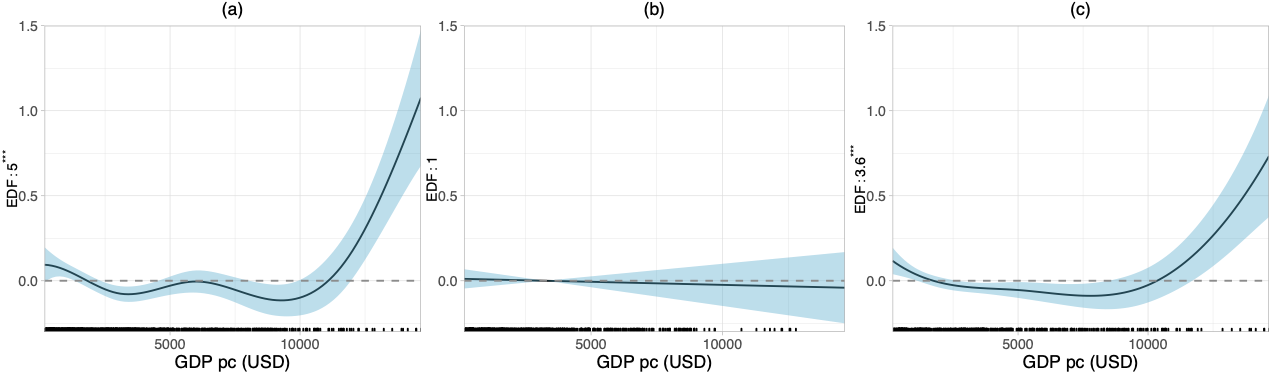

Overall, a higher level of real GDP per capita until $50,000 boosts inflation. The effect flattens beyond this threshold. However, in low and middle-income countries the picture looks strikingly different. Before the crisis, hardly any impact on inflation can be noticed (Figure 4, panel b). Since then, a weak negative association at income levels below $10,000 is followed by an inflationary upsurge beyond this income level (panel c). Real GDP growth fuelled inflation but was less important than real GDP per capita. The output gap is non-linearly associated with inflation and plays a minor role in comparison with GDP per capita but outperforms GDP growth.

Figure 4 The (non-)linear effect of GDP per capita (US $) on log inflation in low- and middle-income countries, across the entire time period (panel a), before the crisis (panel b) and after the crisis (panel c)

Note: Interpretation of the y-axis is only relative with respect to log inflation.

Policy implications

We provide four types of results, which have policy implications. The first relates to monetary policymaking. What matters most for the inflation process is the interaction of energy prices with energy rents. The effect arising from money growth has been weak and less relevant than credit growth, whose effect seems to have even become negative since the Global Crisis. This suggests that monetary policy measures geared towards stimulating credit creation with the final goal to step up inflation may backfire. An inflation target has little explanatory power. More relevant are exchange-rate arrangements. Echoing the findings reported in Baumann et al. (2021b), our analysis yields only a weak association between central bank independence and inflation. Second, from a variety of political factors, the most compelling result relates to civil liberties. Third, there is only a weak connection between public debt and inflation. Finally, two structural forces – population ageing and ICT capital formation – affect the outcomes but in opposite directions. From a methodical point of view, we found that a data-driven machine learning approach outperforms panel regressions informed by economic theory.

Authors note: The views, opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this column are strictly those of the authors. They do not necessarily reflect the views of the Swiss National Bank (SNB). The SNB takes no responsibility for any errors or omissions in, or for the correctness of, the information contained in this column.

References

Baumann, F M, E Rossi and A Volkmann (2021a), “What Drives Inflation and How? Evidence from Additive mixed Models Selected by cAIC”, Swiss National Bank Working Paper 2021-12. Available at:

Baumann, F M, M Schomaker and E Rossi (2021b), “Estimating the Effect of Central Bank Independence on Inflation Using Longitudinal Targeted Maximum Likelihood Estimation”, Journal of Causal Inference 9(2), 1-38.

Ehrmann, M, M Jarociński, C Nickel, C Osbat and A Sokol (2020), “Inflation in a changing economic environment: Insights from a conference at the ECB”, VoxEU.org, 5 February.

Friedman, M (1970), “The Counter-Revolution in Monetary Theory”, Institute of Economic Affairs.

Friedman, M (1974), “Monetary Correction: A Proposal for Escalator Clauses to Reduce the Costs of Ending Inflation”, IEA Occasional Paper, no. 41

Sargent, T J (2013), "Letter to Another Brazilian Finance Minister" in Rational Expectations and Inflation, 3rd edition: Princeton: Princeton University Press.