The information channel of monetary policy (Nakamura and Steinsson 2018) is a recent theory that can potentially explain the puzzling empirical finding that output increases after a contractionary monetary policy shock. According to the information channel theory, economic agents revise their beliefs after an unexpected monetary policy announcement not only because they learn about the current and future path of monetary policy, but also because they learn new information about the economic outlook. This happens because the central bank communicates not only the future path of monetary policy, but also how optimistic it is about the current and future state of the economy. Thus, when the central bank's monetary policy tightening is an endogenous reaction to a future state of the economy that is more positive than markets anticipated, market participants may update their expectations and anticipate that output and inflation might indeed rise. When this happens, the responses to a monetary policy shock may be confounded and incorrectly estimated.

Has the information channel of monetary policy disappeared in the US? In a recent paper (Hoesch et al. 2020), we argue that it has.

We empirically investigate the importance of the information channel of monetary policy over time. We argue that the recent instabilities in the data can potentially mask the disappearance of the information channel, if not properly taken into account. In a nutshell, we revisit the empirical evolution of the information channel over time using methodologies robust to instabilities and find that, although it was clearly important historically, its presence has disappeared in the most recent years.

We note that a crucial assumption behind the information channel is that the central bank has additional knowledge about the state of the economy relative to market participants – that is, it has an ‘information advantage’. When this is the case, market participants will update their information about the state of the economy based on the new information contained in the central bank’s announcements. Hence, focusing on the US, we investigate both how important the ‘information channel’ is, empirically, and whether the Federal Reserve does indeed have an ‘information advantage’ in forecasting macroeconomic variables beyond what is known to private forecasters. We study both the ‘information channel’ and the ‘information advantage’ using methodologies robust to instabilities, based on the fluctuation rationality test developed in Rossi and Sekhposyan (2016). The test provides information on the time evolution of the presence of the information channel and the information advantage.

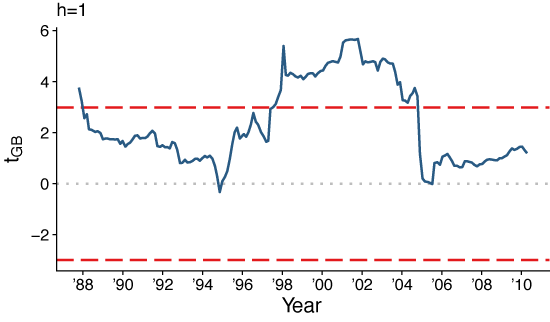

Figure 1 GDP growth: Information advantage fluctuation test

Notes: The solid blue line denotes the Fluctuation t-test statistic estimated in rolling-windows (of size 60 quarters) centred around the date on the x-axis. The test evaluates whether the central bank has an information advantage relative to the private sector in forecasting real GDP growth 1 quarter ahead. The test rejects for test statistic values outside the 5% critical value bands (red dashed lines).

Specifically, Figure 1 plots the empirical findings on the information advantage. The fluctuation test evaluates whether the central bank has an information advantage relative to the private sector (whose forecasts are provided in the Blue Chip Economic Indicator dataset) in forecasting real GDP growth one quarter ahead. When the test statistic (continuous blue line) is outside the bands (dashed red lines), the information advantage is present, while it disappears when the test statistic is inside the bands. Clearly, the information advantage disappeared since 2005. D’Agostino and Whelan (2008) similarly found a decrease in longer horizon predictability in output growth in their sample (ending in 2001); our results highlight, however, that even shorter horizon predictability disappeared, although only more recently.

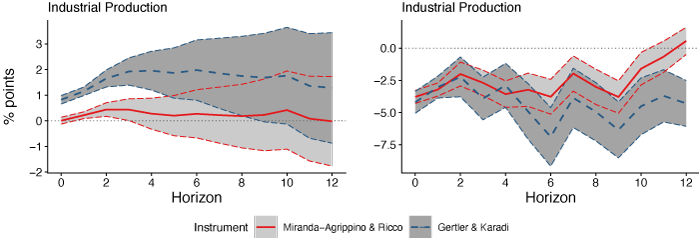

Figure 2 investigates the information channel by splitting the data in two sub-samples, identified by the disappearance of the information advantage. The figure shows the response of the growth rate of industrial production to a contractionary monetary policy shock that can induce a 100 basis-point increase in the one-year rate. Before 2004, output increases after a contractionary monetary policy shock à la Gertler and Karadi (2015) unless one uses the information-robust measure of monetary policy shocks proposed by Miranda-Agrippino and Ricco (2018). On the other hand, output decreases after 2004 no matter whether one uses a standard monetary policy shock or an information-robust shock.

Figure 2 Informationally robust analysis: 1979-2003 and 2004-2014 subsamples

Notes: Responses to monetary policy shocks in two sub-samples: 1/1/1979-12/31/2003 (left panel) and 1/1/2004-31/12/2014 (right panel). The responses are obtained under different identification assumptions: The blue dashed line denotes Gertler and Karadi’s (2015) average monthly market surprise and the red solid line denotes the informationally robust shock by Miranda-Agrippino and Ricco (2018). The shock is normalised to induce a 100 basis-point increase in the one-year rate. The responses are estimated by local projections. Shaded areas are 90% confidence bands based on robust standard errors.

Why have the information channel and the information advantage of monetary policy disappeared? We argue that the disappearance of the information advantage is related to the improved communication strategies implemented by the Federal Reserve. The public has had access to the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) minutes since February 1993, with the lag in the release of the minutes becoming shorter from December 2004 onwards. Furthermore, the Federal Reserve has been releasing FOMC statements since February 1994. On the other hand, the decrease in the short-term information advantage since 2004 is mirrored by a decrease in one- to four-quarter-ahead information advantage in the short-term interest rate. The latter is associated with the explicit introduction of forward guidance in monetary policy at a time when the Fed started communicating its expectations about its own policy decisions.

References

D’Agostino, A, D Giannone and P Surico (2006), “Federal Reserve Information During the Great Moderation”, CEPR Discussion Paper 6594.

D’Agostino, A and K Whelan (2008), “Federal Reserve Information During the Great Moderation”, Journal of the European Economic Association 6(2-3): 609-620.

Gertler, M and P Karadi (2015), “Monetary Policy Surprises, Credit Costs, and Economic Activity”, American Economic Journal: Macroeconomics 7(1): 44-76.

Hoesch, L, B Rossi and T Sekhposyan (2020), “Has the Information Channel of Monetary Policy Disappeared? Revisiting the Empirical Evidence”, CEPR Discussion Paper 14456.

Miranda-Agrippino, S and G Ricco (2018), “The Transmission of Monetary Policy Shocks”, CEPR Discussion Paper 13396.

Nakamura, E and J Steinsson (2018), “High-frequency Identification of Monetary Non-neutrality: The Information Effect”, The Quarterly Journal of Economics 133(3): 1283-1330.

Rossi, B and T Sekhposyan (2016), “Forecast Rationality Tests in the Presence of Instabilities, With Applications to Federal Reserve and Survey Forecasts”, Journal of Applied Econometrics 31(3): 507—532.