In the US today, the professional behaviour of economic historians who are employed in economics departments is similar to that in other fields of economics. Doctoral students in economic history are trained to write articles for refereed economics journals, ideally prestigious publications such as the American Economic Review (AER). Economic historians serve as editors or board members of journals outside the field. They are elected or appointed to offices and committees in the American Economic Association. They serve on government panels.

Economic history is also not activity confined solely to economic historians – there are well-known economists who conduct research in economic history from time to time. This shows the integration of economic history into professional economics (Heckman 1997, Abramitzky 2015, Margo 2017).

Economic history, meet economics

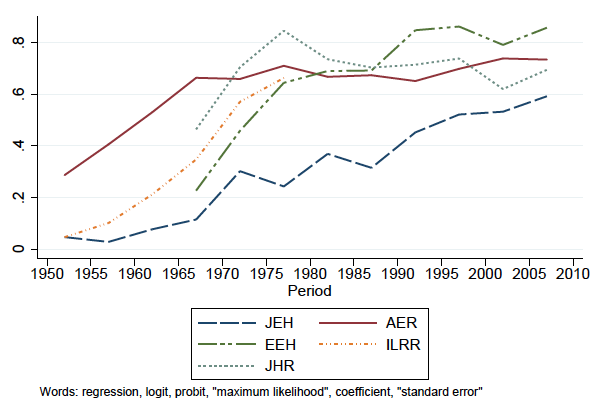

Many have noticed this long-term integration of economic history into economics (Whaples 1991, Abramitzky 2015, Seltzer and Hamermesh 2017). To quantify it, in a recent paper I consider two types of evidence (Margo 2017). The first uses an automated search of digitised journal articles using Google Scholar to produce indices of instances of the use of econometric language. The indices range between zero and one, with higher values implying more frequent appearances of econometric language in the relevant journal. Figure 1 shows the indices for five journals (Journal of Economic History, American Economic Review, Explorations in Economic History, Industrial and Labor Relations Review, and Journal of Human Resources) – two each in economic history and labour economics, and one top-five journal (the AER).

Figure 1 Proportion of articles in five economics journals in which econometric words appear

Use of econometric language has increased in all of them, which is no surprise because economics has become more empirical. In the early 1950s there was little or no econometrics in economic history or labour economics, and already a large gap between both and the AER. There was a sharp rise in econometric language use in the AER between the early 1950s and mid-1960s, at which point the upward trend flattened out. Labour economics caught up quickly but, the process has taken longer in economic history.

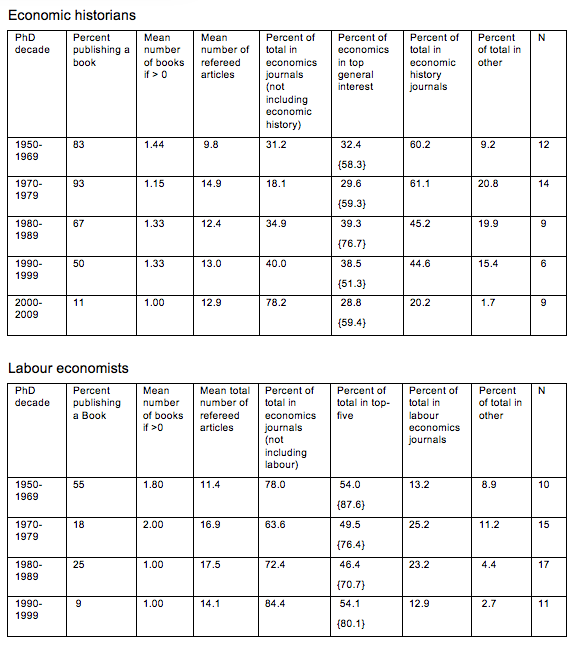

The second body of evidence I studied consisted of the publication histories in books and refereed journal articles, in the 10 years post-PhD, of economic historians with doctorates in economics, and also those of labour economists. The individual scholars are all highly prominent and influential (see Margo 2017 for details). Results are shown in Table 1.

Table 1 Early publication histories: Prominent economic historians and labour economists

Notes: Compiled from CVs. To be included in the sample of economic historians, an individual must meet at least one of the following criteria: President of the Economic History Association; an editor of the Journal of Economic History or Explorations in Economic History; a Fellow of the Cliometrics Society; obtained their first tenured position in a ‘top-10’ economics department or equivalent school of business or public policy. To be included in the sample of labour economists, the individual must be a Fellow of the Society of Labor Economists. Top-Five: American Economic Review, Econometrica, Journal of Political Economy, Quarterly Journal of Economics, Review of Economic Studies.

{ } includes all general interest (e.g. Economic Journal). Other: non-economics journals (for example Journal of American History for historians, and Demography for labour economists).

Among economic historians, I find a long-run increase in the fraction of articles published in economics journals, including in the top-five journals. Total journal productivity is roughly constant across cohorts, so the increase in economics publishing is offset by a decrease in publishing in economic history and other social science journals, and in the probability of publishing a book. These trends begin in the 1980s but there is a structural break for post-2000 PhD cohorts, suggesting a lag in the pace at which economic history integrated into economics. The lag is confirmed in comparison with labour economics. Even in pre-1970s PhD cohorts, prominent labour economists published approximately half of their research articles in top-five journals, with no discernible increase over time.

The cliometrics revolution

A simple analytical framework consisting of initial conditions, labour market structure and incentives, and selection, can help make intellectual sense of the integration of economic history into economics.

- Initial conditions: Just after WWII, as now, economic historians in the US sat either in departments of history or economics, not in stand-alone departments of economic history.1 Economics was growing rapidly, and there was an emerging demand within the discipline for evidence on the historical development of rich countries like the US, to inform policy advice to developing countries and create a factual basis for growth theory. The demand was met by the ‘cliometrics revolution’, in which scholars such as Lance Davis, Stanley Engerman, Robert Fogel, Robert Gallman, Douglass North, William Parker, and many others advocated greater use of economic models and empirical methods in economic history research. The demand in economics for cliometrics has waxed and waned, but has always been present.

- Labour market structure and incentives: I am referring to the ‘overlapping generations’ character of academic labour markets. Senior scholars train junior scholars, and also evaluate junior scholars for tenure and promotion. Junior scholars value tenure and therefore attempt to meet the standards of the discipline in which they are employed when allocating their time, talents, and resources. The structure and incentives ensure that, over time, economic historians working in economics departments would eventually have to meet standards similar to other economists.

- Selection: Today, individuals who matriculate into economics PhD programmes are highly selected for particular traits, such as aptitude for advanced mathematics and related quantitative skills that are not particularly valued in professional history.

Although this framework broadly predicts the integration of economic history into economics, some elements of timing are harder to explain – for example, the structural break in publication histories for post-2000 PhDs. The integration of economic history into economics can be seen as an interesting example of the historical evolution of scholarly identity. Fields like macroeconomics, or labour economics, exist entirely within economics. Economic history is different, however, in that the boundaries cut across history and economics.

As cliometrics became more important in the 1950s and 1960s, the question of identity became more important too. One argument was that cliometricians should meet certain professional norms in history as well as in economics. Robert Fogel was the most notable advocate, but this was widely accepted by the early cliometricians, not just Fogel.

Others argued that economic historians should be gadflies, documenting crucial factors in growth and development that economic theory failed to appreciate. This argument is usually associated with Douglass North but it, too, had many adherents. Taken together, the two impulses created an intellectual space apart from the rest of the economics profession in which the early cliometricians, and their students, could function. These two ideas remained influential into the 1980s and 1990s, but waned after 2000, as the first generation of cliometricians began to leave academia.

Getting the history right

The integration of economic history into economics has brought a tangible personal benefit to economic historians with PhDs in economics, because they are part of an active job market with the relatively high salaries and good working conditions that come with an economics doctorate. This beneficial outcome is not universally true for economics and history as a whole, however. Obviously, the past has useful economics (McCloskey 1976), and it’s a good thing that economists of all persuasions embrace historical evidence more readily than just a few decades ago. As integration continues, however, economic history could become subsumed entirely into other fields. If this were to happen, the demand for specialists in economic history might dry up, to the point where obscure but critical knowledge becomes difficult to access or is even lost. In this case, it becomes harder to ‘get the history right’.

Professional historians interested in economic history must bridge a yawning disciplinary divide to ‘get the economics right’ but have few incentives to do so. An example is the work by professional historians on the history of capitalism, criticised by cliometricians for errors in economic logic and empirical analysis (Hilt 2017). Finding it difficult to tell the players without a score card, the general reading public are the losers.

Historians of economic thought study the evolution of economic ideas and methods of analysis. This evolution is not independent of the institutions and incentives that shape the day-to-day behaviour of professional economists. Economic history is a revealing case study.

References

Abramitzky, Ran (2015), ‘Economics and the Modern Economic Historian,’ Journal of Economic History 75 (December): 1240-1251.

Heckman, James J (1997), ‘The Value of Quantitative Evidence on the Effect of the Past on the Present,’ American Economic Review Papers and Proceedings 87 (May): 404-408.

Hilt, Eric (2017), ‘Economic History, Historical Analysis, and the “New History of Capitalism”,’ Journal of Economic History 77 (June): 511-536.

Margo, Robert A (2017), ‘The Integration of Economic History into Economics,’ NBER working paper 23538.

McCloskey, D N (1976), ‘Does the Past Have Useful Economics?’ Journal of Economic Literature 14 (June): 434-461.

Selzer, Andrew J and Daniel S Hamermesh (2017), ‘Co-Authorship in Economic History and Economics: Are We Different?’ NBER working paper 23404.

Whaples, Robert (1991), ‘A Quantitative History of the Journal of Economic History and the Cliometrics Revolution,’ Journal of Economic History 51 (June): 289-301.

Endnotes

[1] Departments of economic history exist in the UK and Europe. It would be interesting to research whether the professional behaviour of economic historians in these departments has differed from those who have worked in economics or history departments, this is beyond the scope of this article.