Existing research on intergenerational mobility shows that family inputs are strongly related to the lifetime outcomes of children. We see substantial intergenerational persistence between parents and children in income (Björklund and Jäntti 2011, Solon 1999), educational attainment (Black and Devereux 2011, Björklund and Salvanes 2011, Dodin et al. 2021), occupational status (Long and Ferrie 2013, Ward 2020), IQ (Black et al. 2009, Anger and Heineck 2010), and personality traits (Dohmen et al. 2008). Adermon et al. (2021) have gone beyond the immediate family to show a strong relationship between extended family members’ educational attainment and children’s outcomes. Yet these analyses have stopped short of identifying what underlying family characteristics actually determine these patterns of intergenerational persistence of outcomes and, importantly, to what extent these characteristics are set in stone or are subject to change.

Understanding the causes of the intergenerational transmission matters from a policy perspective. If genetic factors or dynastic predispositions for specific subjects were to drive the intergenerational transmission, the role for education policy would be limited. However, the implications are different if the intergenerational transmission of subject-specific skills also reflects the quality of formal or informal education. For instance, if skill transmission can be altered by the education system, the economic benefits of improving school quality come not only from the cognitive skills of the current generation but also from the lasting impact on family outcomes through the transmission of higher skills to their offspring.

First causal evidence on cognitive skill transmission within the family

We present novel evidence on the intergenerational transmission of cognitive skills by compiling a dataset linking maths and language skills of parents to maths and language skills of their children (Hanushek et al. 2021). The Intergenerational Transmission of Skills (ITS) database matches assessment data on parent skills in maths and languages around age 13 (collected in 1977, 1982, and 1989) with register data from the Netherlands on their children’s skills in the same subjects elicited by similar tests at about the same age between 2006 and 2019 (Jacobs et al. 2021). The combined dataset also provides information about a host of other characteristics, such as grandparental education and children’s future education choices, for more than 25,000 parents and 40,000 of their children.

The intergenerational skill data enable us to make direct causal inferences about how status of family outcomes is preserved over generations. We pursue a novel approach to identifying the impact of parent’s skills on their child’s skills by exploiting within-family between-subject variation in skills. By investigating how differences in a child’s skills between maths and languages relate to their parent’s skill differences in the same subjects, all observed and unobserved influences of family, school, and neighbourhood that do not differentially affect the two skill domains are eliminated.

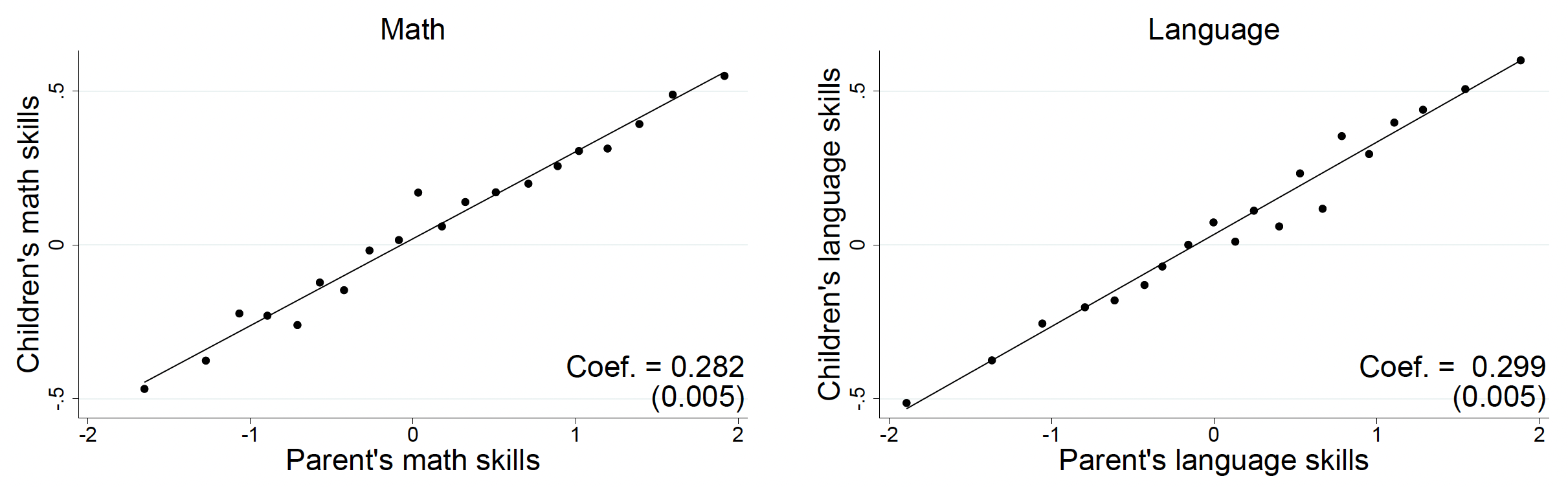

We find that the cognitive skills of parents are highly correlated with the skills of their offspring. Figure 1 shows the results by subject. An increase in parent skills by one standard deviation is associated with an increase in child skills of 0.28 (0.30) standard deviations in math (language). While we can control for various grandparent characteristics (i.e., education and occupational status) and even for the municipality of the parent’s school, we fear that any subject-specific results will be biased by omitted variables simultaneously affecting the cognitive skills of parents and children.

Figure 1 Binned scatterplots of child cognitive skills and parent cognitive skills

Notes: The figure displays two binned scatterplots showing the strength of parent-child transmissions in math skills (left) and language skills (right). To construct the figure, we divided parent cognitive skills into 20 ranked equal-sized groups and plotted the mean of the children cognitive skills against the mean of the parent skills in each bin. The best-fit line, the coefficient, and the standard error (clustered at the parent level) are calculated from bivariate regressions on the micro data.

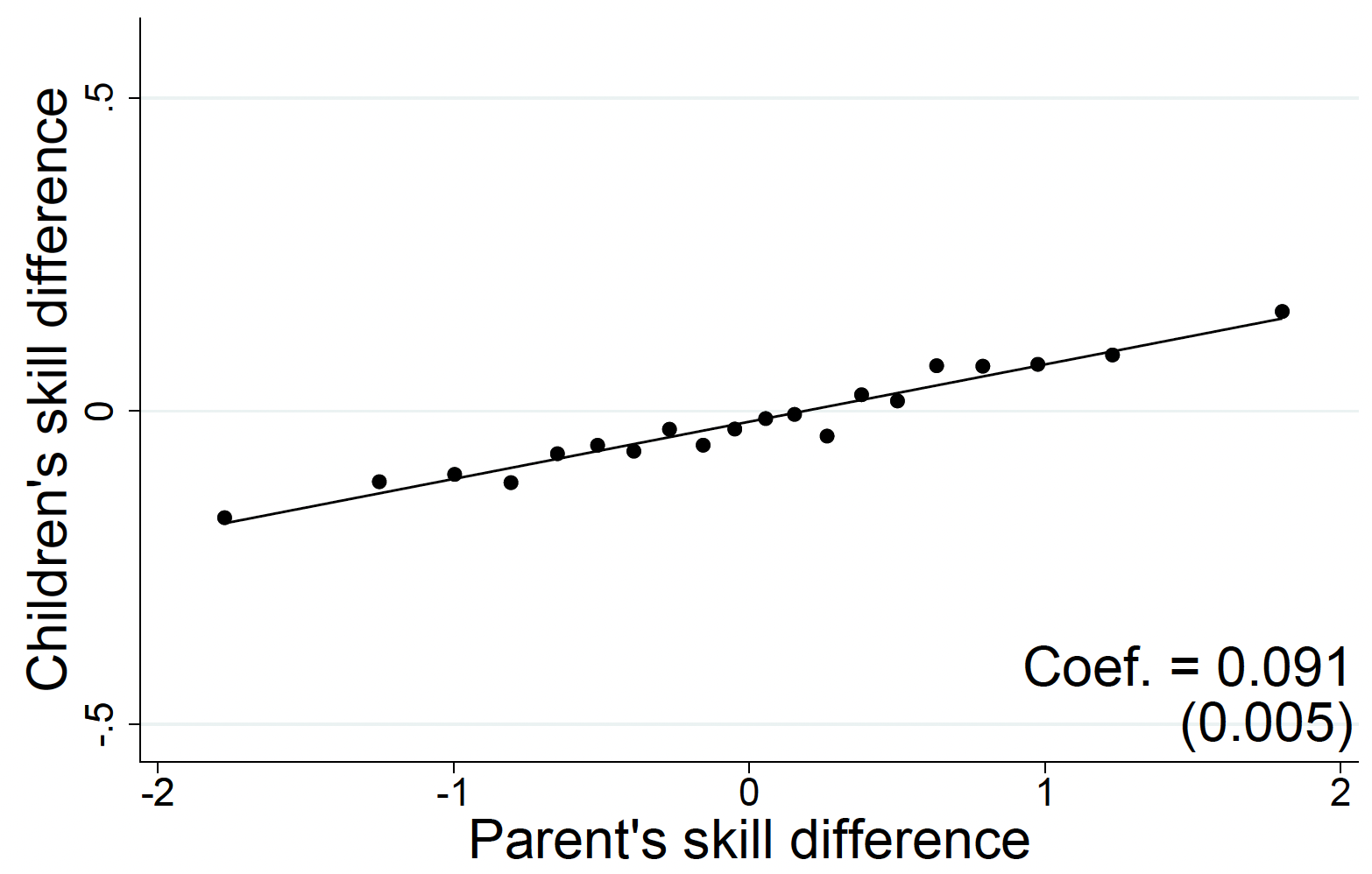

The within-family between-subject model addresses these concerns by eliminating all influences (observed or unobserved) that do not differentially affect skills. Figure 2 shows the results from the between-subject model, plotting the difference in child skills against the difference in parent skills. Parents who perform relatively better in math than in language are significantly more likely to have children who are relatively better at math compared to language (and vice versa). In terms of magnitude, a one-standard-deviation increase in parent skills increases the skills of children by about 0.1 standard deviations.

Figure 2 Binned scatterplot of child and parent cognitive skill differences

Notes: The figure displays a binned scatterplot showing the strength of parent-child transmissions in math-language skill differences. To construct the figure, we divided parent cognitive skills into 20 ranked equal-sized groups and plotted the mean of the children cognitive skills against the mean of the parent skills in each bin. The best-fit line, the coefficient, and the standard error (clustered at the parent level) are calculated from bivariate regressions on the micro data.

The between-subject estimate of the strength of intergenerational transmission is substantially lower than the subject-specific estimates. However, while the subject-specific estimates reflect unmeasured family factors which potentially lead to bias, they also reflect common cognitive skills. Both are eliminated in our between-subject model. Thus, the between-subject estimate of the intergenerational transmission parameter can be considered a lower bound of the total effect of cognitive skills of parents on the cognitive skills of their children.

We also show that subject-specific parent skills influence the long-run path of children in terms of study choice. Children of parents with one standard deviation higher maths skills (relative to language skills) are 2.7 percentage points (or 6.4 %) more likely to choose STEM courses during high school and are 1.1 percentage points (or 3.4 %) more likely to choose a STEM field of study in tertiary education. Interestingly, despite the fact that females are generally less likely to choose STEM tracks than males, the strength with which parental skills translate to STEM choices does not differ by gender.

The role of the education system

The implications of the strong intergenerational transmission of cognitive skills depend importantly on where parent skills originate and whether they can be altered. If, for example, parent skills were entirely genetic in origin and immutable, we might be concerned that potential income mobility, as significantly determined by cognitive skills, is limited. We are unable to describe the full range of influences on parental cognitive skills, but we can provide insights into one key component – the influence of the formal education system. Specifically, we use skill differences between math and language of parents’ classroom peers to develop unique instrumental variables (IV) that relate to the skill differences of parents. In other words, we look at just the impact of differences between math and language skills of parents that are directly related to the math or language intensity of their educational experiences (driven by, for example, subject-specific teacher or school quality). In addition to providing insight into the malleability of family cognitive skill influences, the IV estimation also provides a way of dealing with the possibility of bias from omitted subject-specific proclivities of families.

The resulting IV estimates of the strength of the intergenerational transmission are strikingly similar to our baseline estimates – reinforcing a causal interpretation of the between-subject model. Extensive specification and robustness checks suggest that the exclusion restriction for our peer-based instrument holds.

Policy implications

Our results carry an important policy message regarding the long-run value of good educational environments in alleviating educational inequalities. Strong persistence in the transmission of human capital across generations is often seen as an obstacle to equality of opportunity. But this might be only partly true. Our results clearly show that the part of parent cognitive skills that is malleable by educational quality also carries over to future generations. Thus, the crucial challenge for education policy remains to guarantee equal access to good education. If children in families with more favourable pre-birth and post-birth factors also predominantly get access to better educational environments, educational inequalities across generations will persist and perhaps increase. However, if policy succeeds in providing better education to children in families with less favourable pre-birth or post-birth factors, the benefits of this will also spill-over to future generations.

References

Adermon, A, M Lindahl, M Palme (2021), "Dynastic human capital, inequality, and intergenerational mobility", American Economic Review 111 (5): 1523-48.

Anger, S and G Heineck (2010), "Do smart parents raise smart children? The intergenerational transmission of cognitive abilities", Journal of Population Economics 23 (3): 1255-1282.

Björklund, A and M Jäntti (2011), "Intergenerational income mobility and the role of family background", in B Nolan, W Salverda, and T M Smeeding (eds), The Oxford Handbook of Economic Inequality, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Björklund, A and K G Salvanes (2011), "Education and family background: Mechanisms and policies", in S Machin, E A Hanushek, and L Woessmann (eds), Handbook of the Economics of Education 3, Amsterdam: North Holland, pp. 201-247.

Black, S E and P J Devereux (2011), "Recent developments in intergenerational mobility", in O Ashenfelter and D Card (eds), Handbook of Labor Economics 4(B), Amsterdam: North Holland, pp. 1487-1541.

Black, S E, P J Devereux, K G Salvanes (2009), "Like father, like son? A note on the intergenerational transmission of IQ scores", Economics Letters 105 (1): 138-140.

Dodin, M, S Findeisen, L Henkel, D Sachs, and P Schüle (2021), "New evidence on social mobility in Germany", VoxEU.org, 24 December.

Dohmen, T, A Falk, D Huffman, and U Sunde (2008), "The intergenerational transmission of risk and trust attitudes", VoxEU.org, 5 July.

Hanushek, E A, B Jacobs, G Schwerdt, R van der Velden, S Vermeulen, and S Wiederhold (2021), "The intergenerational transmission of cognitive skills: An investigation of the causal impact of families on student outcomes", NBER Working Paper No. 29450.

Jacobs, B, S Vermeulen, and R van der Velden (2021), The Intergenerational Transmission of Skills Dataset, ROA Technical Report ROA-TR-2021/7, Research Centre for Education and the Labour Market, Maastricht University.

Long, J and J Ferrie (2013), "Intergenerational occupational mobility in Great Britain and the United States since 1850", American Economic Review 103 (4): 1109-37.

Solon, G (1999), "Intergenerational mobility in the labor market", in O Ashenfelter and D Card (eds), Handbook of Labor Economics, Amsterdam: Elsevier pp. 1761-1800.

Ward, Z (2020), "The not-so-hot melting pot: The persistence of outcomes for descendants of the age of mass migration", American Economic Journal: Applied Economics 12 (4): 73-102.