Nearly 90% of central banks worldwide are weighing the pros and cons of issuing a central bank digital currency (CBDC) (Boar and Wehrling 2021). The ECB launched the investigation phase for a digital euro project over the summer. No decision has been taken as to whether to issue a digital euro.

One of the aspects the ECB is investigating is whether it would be possible to use the digital euro in cross-border contexts, and under which conditions. Many other central banks are also reflecting on whether they would allow non-residents to access their own digital currency – if they decided to introduce one (CPMI et al. 2021).

Decisions about the issuance and design of CBDCs require a careful assessment of the trade-offs between risks and opportunities (e.g. Agur et al. 2021, Bindseil and Panetta 2020, Brunnermeier and Niepelt 2019, Fernández-Villaverde et al.. 2021, Niepelt 2020, Uhlig and Xie 2021). The international dimension makes that assessment more challenging still. So, it is already worth thinking about the implications of the cross-border use of CBDCs.

This is where research can help policy. The literature on the international aspects of CBDCs is still in its infancy. Two sets of research questions are particularly relevant for global macro-financial policy: What is different about CBDCs? And what are their implications for international central bank cooperation?1

What we know

Research points to three main implications of allowing non-residents unrestricted access to a given CBDC.

First, a CBDC that can be used outside the jurisdiction where it is issued might increase the risk of digital currency substitution – or digital ‘dollarisation’ (e.g. Brunnermeier et al. 2021). If a foreign CBDC were to be widely adopted, this might lead to the domestic currency losing its function as a medium of exchange, unit of account and store of value – ultimately impairing the effectiveness of domestic monetary policy and raising financial stability risks. These risks are particularly relevant for emerging markets and less developed economies that have unstable currencies and weak fundamentals. Currency substitution could also occur in small advanced economies open to trade and integrated in global value chains (Ikeda 2020). It is hard to gauge in advance how significant the risks of digital currency substitution could be, and in which currencies this substitution could occur. In any case, according to the (unwritten) code of central banking, the introduction of a CDBC in one jurisdiction must do no harm.2 In particular, it must not put the financial system of other jurisdictions at risk.

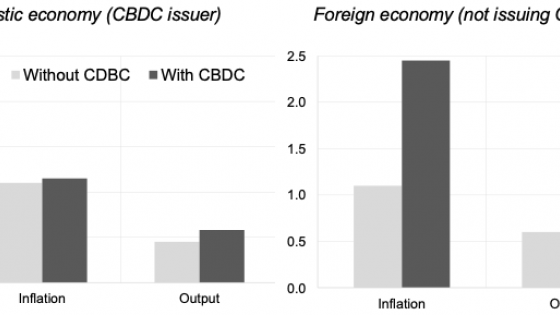

Second, issuing a CBDC can magnify the cross-border transmission of shocks, increase exchange rate volatility and alter capital flow dynamics. One reason for this is that CBDCs combine characteristics such as scalability, liquidity and (potentially) renumeration, which make them appealing relative to financial assets that are traded internationally. Research finds that introducing a CBDC available to non-residents ‘super charges’ uncovered interest rate parity – the standard relation between interest rate differentials across countries and the exchange rate (Ferrari et al. 2020). That, in turn, leads to a stronger rebalancing of global portfolios in response to shocks, and to higher exchange rate volatility. Economies not issuing a CBDC are then subject to stronger spillovers. And their central banks need to be more reactive to output and inflation fluctuations, which reduces their policy autonomy.

Finally, research suggests that issuing a CBDC which can be used by non-residents might have an impact on the international role of currencies. The costs of cross-border payments might fall, which may enhance the role of a currency as a global payment unit. And the specific features of a CBDC – such as safety, liquidity, efficiency and scalability – might further bolster its international use. But there is a flipside to this: broader international demand may cause the exchange rate to appreciate. This could weigh on the currency’s attractiveness as an invoicing or settlement unit for exports in other jurisdictions and, in turn, reduce global interest in the currency. On the whole, model simulations by ECB staff suggest that issuing a CBDC would support the international role of a currency, albeit not to a particularly large extent (ECB 2021a). In other words, economic fundamentals underpinning international currency use matter more.

What is different about CBDCs?

Existing research often models CBDCs as safe and liquid instruments. That is convenient as it allows us to draw on standard macro-monetary models, with some tweaks here and there. But to truly understand the risks and opportunities of CBDCs, we need to take them more seriously and acquire a deeper understanding of what makes them different from other monetary and financial instruments.

Consider a few examples. First, how much of the discussion on the risks arising from digital dollarisation is new? The determinants emphasised in existing research often seem all too reminiscent of the macro literature of the 1990s on dollarisation. It would be good to understand what is truly unique about CBDCs now as compared with dollarisation back then. For instance, maybe the determinants are unchanged but CBDC makes dollarisation more likely by lowering transaction costs. Or perhaps CBDCs could be bundled with other useful services, such as privacy services, rewards or conditional payments.

Second, on international spillovers, introducing any other internationally traded safe and liquid instrument, such as a highly rated bond, into a macro model would also produce strong spillovers. So, can we truly apply the same insights to CBDCs? We need to make sure we do not miss relevant channels and idiosyncrasies.

Third, concerning the international role of currencies, the effects obtained are likely calibration- or estimation-dependent. Under which conditions will standard economic fundamentals remain the main drivers of international currency status? Research so far indicates that digitalisation does not change anything fundamental. Yet, to what extent would CBDCs still have the potential to affect the configuration of global reserve currencies and the stability of the international monetary system?

International cooperation

Other questions naturally emerge when considering the international context. One such question relates to global cooperation. Allowing non-residents to use a CBDC issued in another jurisdiction may give rise to externalities. How much international cooperation is desirable to internalise them is open to debate.

So far, the academic literature provides limited guidance. But international cooperation offers clear benefits: exchanging information allows us to share our experiences about possible problems and solutions, and find consensus on important economic, financial and regulatory issues of common interest. There might be gains from reflecting on common standards to make CBDC projects interoperable, for instance to move from cross-border use of CBDCs to cross-currency payments between CBDCs. Cooperation is not without costs, however. And the costs increase with the number of central banks involved and with their diverse objectives, legal frameworks, financial structures, mandates and preferences, which would likely be reflected in different CBDC designs.

So the natural question to ask is: How much global cooperation is optimal? One might be tempted to aim for uniform standards for CBDCs – a ‘one size fits all’ approach. But whether meaningful cooperation is possible if conditions differ sharply across countries is unclear. Take privacy – an important design feature of a digital euro that was raised by members of the public and professionals in the public consultation the ECB concluded earlier this year (ECB 2021b). A concrete question is: How could a jurisdiction with stringent requirements on traceability of payments allow cross-currency transactions with a jurisdiction granting higher privacy standards? Privacy is unlikely to be equally important in all regions of the world. And where diverse preferences exist, some stakeholders might not see much merit in enforcing global standards.

Still another point to consider is the existence of strategic interactions – where decisions of one player depend on the actions of the other players – as they can tilt the balance of the benefits and costs of global cooperation. Many countries are simultaneously reflecting on CBDCs. But strategic interactions have not been much studied in the context of CBDCs, and the international dimension even less so.

What the optimal timing of actions is, for instance, is not well understood. It is tempting to see the field of CBDCs as a clean slate at the moment. But this will not last. The countries that have already introduced their own CBDCs, such as the Bahamas, cannot set global standards. This will change if major economies launch their own CBDCs. Can the ‘pioneer’ central banks that have decided – or are deciding – on the design of CBDC based on their own considerations be expected to wait for a consensus to emerge on global standards before moving ahead? The costs and benefits of being the first to issue a digital currency are not well understood either. Is it better to issue a digital currency first – and aim to set standards for others, while putting domestic objectives at risk – than it is to get it right?

This list of open questions is not exhaustive, of course. But by addressing them, research would not only push the frontier of knowledge, it would also provide the conceptual backbone and evidence that could usefully inform future policy decisions on CBDCs.

Authors’ note: The opinions expressed in this column are our own and not necessarily those of the ECB.

References

Agur, I, A Ari and G Dell’Ariccia (2021), “Designing central bank digital currencies”, Journal of Monetary Economics.

Bindseil, U and F Panetta, (2020), “CBDC remuneration in a world with low or negative nominal interest rates”, VoxEU.org, 5 October.

Boar, C and A Wehrling (2021), “Ready, steady, go? – Results of the third BIS survey on central bank digital currency”, BIS Papers, No. 114, January 2021.

Brunnermeier, M K and D Niepelt (2019), “On the equivalence of private and public money”, Journal of Monetary Economics 106: 27-41.

Brunnermeier, M, H James and J P Landau (2021), “Digitalization of money”, BIS Working Papers No. 941.

Committee on Payments and Market Infrastructures, BIS Innovation Hub, IMF and World Bank (2021), Central bank digital currencies for cross-border payments, Report to the G20, July.

ECB (2021a), “Central bank digital currency and global currencies”, The international role of the euro, July.

ECB (2021b), “Eurosystem report on the public consultation on a digital euro”, April.

Ferrari, M, A Mehl and L Stracca (2020), “Central bank digital currency in an open economy”, CEPR Discussion Paper 15335.

Fernández-Villaverde, J, D Sanches, L Schilling and H Uhlig (2021), “Central bank digital currency: Central banking for all?”, Review of Economic Dynamics 41: 225-242.

Group of central banks (2020), Central bank digital currencies: foundational principles and core features, Joint report by the Bank of Canada, European Central Bank, Bank of Japan, Sveriges Riksbank, Swiss National Bank, Bank of England, Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve and Bank for International Settlements, October.

Ikeda, D (2020), “Digital money as a unit of account and monetary policy in open economies”, Institute for Monetary and Economic Studies No. 20-E-15, Bank of Japan.

Niepelt, D (2020), “Digital money and central bank digital currency: An executive summary”, VoxEU.org, 3 February.

Uhlig, H and T Xie (2021), “Parallel digital currencies and sticky prices”, NBER Working Paper No. 28300.

Endnotes

1 There are also technical and policy discussions in international fora on how CBDCs could facilitate cross-border payments through different degrees of integration and cooperation – ranging from basic compatibility with common standards to the establishment of international payment infrastructures – in which the ECB and other central banks are involved.

2 This has been stressed, for example, in Group of central banks (2020).