Editors' note: This column first appeared as a chapter in the VoxEU ebook, Brexit Beckons: Thinking ahead by leading economists, available to download free of charge here. Listen to Patrick Honohan discuss Ireland and Brexit in the Vox Talk interview here.

Ireland is the remaining EU country most exposed to Brexit. When Britain decided to join the EEC in 1973, it was a foregone conclusion that Ireland would follow. But Ireland’s ancient continental links were relevant, and those links were consolidated over the following half century to the point where Brexit has scarcely awoken any interest for Ireland to consider following suit.

Instead, the concern in Ireland is about the consequences of a future in which the legal basis for the UK’s economic relations with the EU – and hence with Ireland – is thrown into doubt.

Economic links between Ireland and the UK have declined over the past decades, but this should not be exaggerated.

- On the eve of the WWII almost 94% of Irish exports went to the UK (and still almost 75% 50 years ago);

- Today, the UK’s share of Irish exports is less than 15%.

In considering these figures, however, account needs to be taken of the high import content of much of Ireland’s other trade. That is, the local content of Ireland’s exports to the UK is relatively high. If fully weighted by employment content, the UK share would be closer to a quarter. Half of Ireland’s agricultural exports still go to the UK, and it is the biggest customer for the rapidly growing export of services. The three remaining Irish headquartered banks continue to have a sizable loan book in the UK.

The UK’s share of Ireland’s imports has held up better than exports, especially when it comes to consumer goods. The value of imports coming from the UK in recent years has still been almost the same as from the rest of the EU put together.

Another striking fact is that, for those Irish companies that have expanded abroad, the UK is the dominant destination. Almost one in three of the workers these firms employ abroad are located in the UK.

While the US is more important in certain fields – notably as a source of inward direct investment – and while the rest of the EU as a whole has overtaken the UK, by any overall reckoning, the UK is still the largest single economic partner of Ireland.

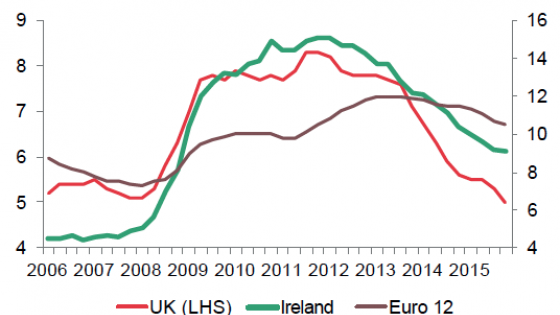

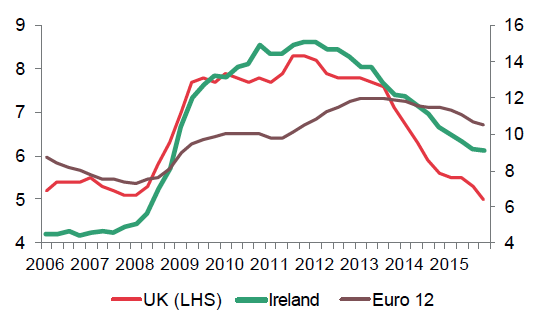

And the close integration of the labour market on both sides of the Irish Sea has represented an important safety valve for the Irish economy in the recent downturn. The relatively rapid reduction in the rate of unemployment from over 15% in 2012 to under 8% today owes something to job growth in the UK. This is illustrated by the manner in which the dynamics of unemployment in Ireland have tracked those of the UK much more closely than the Eurozone (Figure 1).

Figure1 Unemployment rates: Ireland and UK

The impact all depends upon the UK’s new relationship with the EU

It is of course hard to tell how much will change in this relationship as a result of Brexit. If Britain were to retain access to the Single Market, continuation of the long-standing pre-EEC freedom of movement for Irish citizens in the UK would mean little change.

If the UK were to withdraw from the Single Market, though, there could be sizable impacts in terms of a redirection of trade, or what might be called ‘trade re-diversion’.1 This has two sides to it: redirection of exports, and redirection of imports.

On the export side, agriculture is the obvious focus. Given the high level of EU protection on its agriculture, extra-EU producers currently face sizable EU tariff barriers – including on some of the products that Ireland exports. While the UK is inside the EU, such barriers provide a preference for Irish goods that will disappear when the UK leaves. Under such circumstances (and even if Britain were to adopt a policy of unilateral free trade), some of Ireland’s agricultural produce would be diverted into the remainder of the EU, presumably implying some price falls (Matthews 2015).

It is the smaller, locally owned Irish firms that would be most impacted by trade re-diversion from the introduction of tariffs by Britain, which has traditionally been the first overseas market for expanding small firms in Ireland. Breaking into that market is greatly facilitated by a common language and similar legal systems. But if it entailed administrative and tariff barriers to such trade, Brexit would make the initial step of expanding beyond the Irish market more difficult.

Will banks relocate to Ireland?

The preference logic, however, runs in the opposite direction for other sectors. If UK-based firms face new barriers outside the EU, some re-diversion would arise that favours the replacement of UK providers with Irish ones. The most-discussed sector in which this might occur is financial services, reflecting Ireland’s already sizable market share in sectors such as fund management and the similarity between Ireland’s legal system and the UK’s. The scale of net benefit to Ireland from any diversion in this sector remains to be seen; the value-added retained in Ireland from some export services has been strikingly low. The Irish regulatory authorities will doubtless maintain their current alert supervision of regulated financial services, mindful of previous failures.

This form of trade re-diversion would probably entail multinational firms repositioning their European headquarters to Ireland from the UK. To the extent that firms shift some staff to Dublin, upward pressure in the short-term on commercial and residential property prices could be expected; remaining excess supply of property is found only outside the capital. Such pressures would be eased by infrastructural investment.

Impact on inward FDI

The net impact of Brexit on inward foreign direct investment to Ireland will depend upon many factors. For example, if the UK does try to forestall declining investment by lowering corporate profits tax, this would surely have an effect on Ireland’s market share (Davies et al. 2016).

The sizable retail market share of UK firms such as Tesco and Marks & Spencer highlights the likely impact on this sector from the application of the EU’s common external tariff. Diversion of some of this demand to higher cost sourcing will mean permanently higher consumer prices, an effect which would be exacerbated if some of the UK firms were to withdraw from the market, thus reducing competition.

Logistical challenges and natural gas vulnerabilities

Well over half of the tonnage of goods that are shipped from Irish and EU ports travel via the UK. Thus, logistical obstacles to the flow through the UK of merchandise trade between Ireland and the remainder of the EU will add costs, albeit presumably of second-order importance.

Additional vulnerability comes from the fact that, at present, Ireland’s only physical international electricity and gas interconnections are with the UK (ESRI 2015). Other regions of the EU, such as Finland and Lithuania, trade electricity freely with Russia so that Brexit is unlikely to prevent trade in electricity. But Ireland would no longer benefit from EU requirements for the UK to share its supplies in the event of a major disruption to EU gas supplies, a consideration of some significance given the high dependence of the Irish electricity system on gas.

Land borders on the Irish island

There is universal reluctance to see the reintroduction of physical border controls on the island of Ireland. Their absence is an important symbol of the success of the peace process encapsulated in the Good Friday Agreement of 1998, and this is a consideration that must not be downplayed in designing the new arrangements for controlling the movement of goods and persons (Todd 2016). It should not be beyond the capacity of modern technology to design immigration control and customs mechanisms that do not have to rely on physical border controls on the island.2

Concluding remarks

Ireland is one of the most globalised economies in the world. While a changed environment for the relations with its most important economic partner would be a setback – and official and private forecasters are already shaving half a percentage point off their growth forecasts for the coming year – it should not blunt Ireland’s strategic potential. Nevertheless, negotiators will need to pay close attention to the detailed design of the Brexit regime to ensure that unnecessary collateral damage is not done to a connexion which, for good or ill, has persisted for centuries.

References

Davies, R. B., I. Siedschlag and Z. Studnicka (2016), “Corporate Taxation and Foreign Direct Investment in EU Countries: Policy Implications for Ireland”, ESRI Quarterly Economic Commentary, Summer.

Economic and Social Research Institute (ESRI) (2015), Scoping the Possible Economic Implications of Brexit on Ireland, Dublin.

Matthews, A. (2015), “Implications of British Exit from the EU for the Irish Agri-food Sector”, TEP Working Paper 0215, Trinity College Dublin.

Todd, J. (2015), “The Vulnerability of the Northern Ireland Settlement: British-Irish Relations, Political Crisis and Brexit”, Etudes Irlandaises 40(2): 61-73.

Endnotes

[1] ESRI (2015) suggests that merchandise exports to the UK could fall by as much as 20% in this scenario, presumably entailing diversion of quantities to other markets at lower net prices.

[2] For many years the level of cross-border trade within the island has been well below what would be predicted from a gravity model.